Manorial Lordships and Statutory Declarations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Middle Ages the Middle Ages (Or Medieval Times) Was a Time of Lords and Peasants; Manors and Huts; Very Rich and Very Poor

The Middle Ages The Middle Ages (or Medieval Times) was a time of lords and peasants; manors and huts; very rich and very poor. The first half of the middle ages is often referred to as the Dark Ages. After the fall of the Roman Empire, a large amount of Roman culture and knowledge was lost. This was because the Romans kept excellent records of events that occurred. Therefore, historians refer to the time after the Romans as dark because there was no central government recording the events. The Lord of the Manor Life in the Middle Ages would be very different depending on which social class you fell into and how much money (or wealth) you had. For safety and defence, people in the Middle Ages formed small communities around a Central Lord or Master. These communities were called Manors and the ruler was called the Lord of the Manor. The Manor Each manor would have a castle (or manor house), a church, a village, and farm land. Self-Sufficiency Each manor was largely self- sufficient. This meant that people living in that community would grow or produce all of the basic items they needed for food, clothing, and shelter. To meet these needs, the manor had buildings devoted to special purposes, such as: The mill for grinding grain The bake house for making bread The blacksmith for creating metal goods. Power and Wealth This pyramid shows the KING power in the country during the Middle Ages. The King is at the top of Loyalty Military Aid the pyramid because he LORDS OF THE MANORS had ultimate power over the whole country. -

Freedmen and Serfs Code of Chivalry

CK_4_TH_HG_P087_242.QXD 10/6/05 9:02 AM Page 116 II. Europe in the Middle Ages Cross-curricular Freedmen and Serfs Teaching Idea The manorial system was the economic side of medieval life. The lord lived Since the King Arthur legends and on the manor surrounded by his knights for protection and enriched by the toil Robin Hood are parts of the Grade 4 of his peasants. Until the 14th century, some peasants, known as serfs, were Core Knowledge Language Arts required to work a certain number of days a year in the lord’s fields and to pay Sequence, be sure to connect the histor- rent in the form of produce. In exchange, the serfs were entitled to cultivate land ical and literary topics. Many teachers for themselves, and the lord had to protect his serfs from attacks by bandits and prefer to read the King Arthur legends the followers of other lords. It was also the duty of the lord of the manor to hear during the study of the Middle Ages. disputes on his manor and to render judgment. Serfs were not free, but they were not slaves either. They could not move from manor to manor, but a lord could not dispossess them. A serf or slave that was granted freedom from his lord was called a freedman. A few peasants were free. They did not owe service to the lord but only a Teaching Idea fixed rent in exchange for land and protection. Encourage students to adopt a “code of chivalry” in the classroom and around Code of Chivalry the school. -

Feudal Baronies and Manorial Lordships

Feudal Baronies and Manorial Lordships The seven years of the Baronage operation on the Internet have seen two messages stressed repeatedly — first, that the only feudal baronies still held in baroniam and capable of being sold with their status intact are those of Scotland, and, second, that genuine manorial lordships are not titles of nobility, and their holders are not qualified to be styled “Lord” (as in “Lord Blogges” or “Lord Bloggeston”). Now as new Scottish legislation is intended to separate baronial titles from the land to which they have been tied for, in some cases, close to 900 years, and thus to allow them, in essence, to be traded in a manner similar to English manorial lordships (with all the risks that entails), many readers have written to ask for an explanation of what is happening and for our views on what will happen in the future. In response, this special edition of the Baronage magazine examines the nature of feudal baronies and manorial lordships. Feudalism and the Barony The feudal system was developed in the territories Charlemagne had ruled, and it was brought to Britain by the Norman Conquest. Under feudalism all land belongs to the King. He grants parts of it to his closest advisers and most powerful warriors, these being known as tenants-in-chief, and they in turn grant parts of their lands to others who could in turn let parts of their holdings. There is thus a chain – King, tenants-in-chief, tenants, sub-tenants. The basic unit of feudalism is the manor – which had existed in Britain before the Conquest but was readily absorbed into the feudal system. -

1 Was Odard, First Lord of Dutton, a Distant Relative of William the Conqueror?

Was Odard, First Lord of Dutton, a Distant Relative of William the Conqueror? Edward Dutton University of Oulu Abstract According to the Dutton tree researched by antiquarian P. H. Lawson, Odard, first Lord of the Manor of Dutton in Cheshire and progenitor of the noted Gentry family the Duttons of Dutton, was related to William the Conqueror on his mother’s and on his father’s side. This article reviews the evidence and argues that Odard was not related to the Conqueror on his mother’s side. Regarding his father’s side, the evidence is perhaps most parsimoniously explained by Odard indeed being a distant relative of the Conqueror’s. However this conclusion is only fractionally more persuasive than the opposite one and accordingly there is good reason to seriously doubt it and reserve judgement.1 Introduction The anonymous author of the 1901 book The Duttons of Dutton remarked that the Cheshire knightly and Gentry family are of particular interest to historians: ‘There is a general historical interest in the family history of the Duttons. They have an undoubted historical descent from one of the followers of William the Conqueror . and were involved in the contests and convulsions of their time.’ He observes that these include, in assorted branches, the Crusades, Agincourt, the Wars of the Roses and the dissolution of the monasteries. 2 The male line of the Duttons of Dutton died out in 1614. But it is the founder of the Duttons of Dutton, Odard, first Lord of the Manor of Dutton, whom I wish to focus on in this article. -

The Revd Thomas Henry Whorwood and His Sons

The Vicar of St Andrew’s Church, Headington and his sons The Revd Thomas Henry Whorwood (1778–1835) was Vicar of St Andrew’s 1804–1835, Vicar of Marston 1805–1833, and Lord of the Manor of Headington 1806–1835 His elder son Thomas Henry Whorwood (1812–1884) was Vicar of Marston 1833–1849 and Lord of the Manor of Headington 1835–1849 His younger son William Henry Whorwood (1817–1843) was a prodigal son The Revd Thomas Henry Whorwood (1778– While his older brother had been alive, the 1835) was the son of Henry Whorwood, Lord Vicar was evidently cowed by him: in 1805 of the Manor of Headington from 1771 to James Palmer, the curate of St Andrew’s c.1800. His mother Mary had died a week after Church, had written to the Bishop saying that giving birth to Thomas Henry and his twin the Vicar was in a state of such dependence on brother William Henry on 7 May 1778. his elder brother that he could not ‘differ from The older brother of the twins, Henry Mayne him materially without danger of starvation’. Whorwood, succeeded to the Lordship of the But as soon as the Vicar stepped into his Manor in c.1800 on the death of their father, brother’s shoes as Lord, he began to show that and was married in 1802. he too had his brother’s vicious streak and As the second son of the Lord of the Manor, lacked the Christian charity that might be ex- Thomas had been destined from birth to enter pected of a vicar: he immediately issued a no- the Church, and in 1785 had gone off to learn tice announcing that ‘Steel traps and other de- his trade at Worcester College in Oxford. -

Are You Being Conned? (Second Edition)

Are You Being Conned? (second edition) Are You Being Conned? No! Of course not! You’re street smart. You’ve been He’s in town on business, well, not really serious around a bit. I mean – you see ’em coming, don’t you? business – he represents a charity. And you’re the sort who in this town would know the right kind of people But look at this one. Smart suit, cut’s a bit old- he ought to meet. Would you enjoy that – introducing fashioned, but it’s clean and has been pressed. Striped your new friend, a real lord, to your old friends? Well, tie; good shoes (you always look carefully at the shoes, would you? don’t you?), hair a bit too long, and an English accent. ____◊____ Perhaps that’s the famous old school tie they talk about in Agatha Christie. Then it’s a few days later and you’re sitting alone, crying into your beer. How could it be your fault? I What’s that they’re saying over there in the corner? mean, there are hundreds of English lords, and you had He’s a lord, an English lord? Well, that could explain to meet the one phony. Just one among hundreds. How his clothes. He looks a bit odd, but then perhaps they bad can your luck be ? One among hundreds ! all do. It’s the inbreeding, you suppose. But now he’s smiling at you. And he’s offering to buy you a drink. But you’re wrong. He wasn’t one alone. -

The Medieval Feudal System

2 Choose the correct answer. The medieval feudal system 1 Nobles and 2 LAND LOYALTY 3 (Lords of the manor) 4 The medieval feudal system Anglo-Saxon England was mainly a society of landowners and farmers. There was already a king, peasants and rich nobles, but if the king needed an army, he used to call on the landowners and farmers to become his soldiers. The Normans had another level of society – knights who fought on horseback and who were ‘professional soldiers’. The knights were supposed to show courage, loyalty, honour and kindness. 1 Which level of society did not exist in Anglo-Saxon England? a nobles b king c knights d peasants Venture Level 2 . The medieval feudal system, p.251 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE The Norman Conquest brought a new type of society to England – the feudal system. The feudal system is a system where the higher classes of society give land to the lower classes in return for loyalty. 2 In the feudal system, what could you receive for your loyalty to the people above you? a 10% of their money b land and protection c an army d honour In the European feudal system, the king of a country owned all the land and had total power. In medieval times, people used to believe that God gave the king the right to rule. The king gave land to any nobles who promised to give him money and knights for his army. Nobles and bishops had to swear an oath to remain loyal to the king. In England, the bishops received money from the king, and everyone else in the country had to pay the church 10% of what they had. -

Briefing Note No. 3 Checklists of Sources: Manors and Estates

Department of History, Lancaster University Victoria County History: Cumbria Project Briefing Note No. 3 Checklists of Sources: Manors and Estates These notes are intended to complement VCH guidance notes on ‘Manors and Estates’ and should be read in conjunction with them: http://www.victoriacountyhistory.ac.uk/local- history/manors-and-estates Where to start will depend in part on the part of Cumbria in which the township/parish you are researching lies: For Cumberland, start with: John Denton’s History of Cumberland, ed. A. J. L. Winchester. Surtees Society Vol. 213 and CWAAS Record Series Vol. XX (Woodbridge, 2010). [only partial coverage but very useful for the medieval estates of which his accounts survive. Where possible, use the footnotes to go back to the primary sources (Cal. Inq. p. m. etc) and cite these rather than Denton himself. Thomas Denton: a Perambulation of Cumberland 1687-1688, including descriptions of Westmorland, The Isle of Man and Ireland, ed. A. J. L. Winchester with M. Wane. Surtees Society Vol. 207 and CWAAS Record Series Vol. XVI (Woodbridge, 2003). [again, where possible check his statements in independent sources] For Westmorland: J. F. Curwen, The Later Records relating to North Westmorland or the Barony of Appleby, CWAAS (Kendal, 1932). 1 W. Farrer, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale Vols. I and II, ed. J. F. Curwen; and J. F. Curwen, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale Vol. III, CWAAS Record Series Vols IV-VI (Kendal, 1923-6). These sources focus on the medieval (and, to a lesser extent, early-modern) centuries. The story of landownership should be followed through to the time of writing. -

Manorial Society of Great Britain, Advice on Buying a Manorial Title

Advice on buying a manorial title ¦ http://www.msgb.co.uk http://www.msgb.co.uk/buying_advice.html Advice on buying a manorial title 1: WHAT IS A MANORIAL LORDSHIP? 1.1: Introduction 1.2: Importance of Solicitors 1.3: Taxation 1.4: British and overseas owners and death 1.5: Land Registration Act, 2002 (LRA) 1.6: Scottish baronies 1.7: Some publications 1.1: Introduction UNDER the laws of real property in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and the Irish Republic, Lordships of the manor are known as ‘estates in land’ and in Courts, where they may crop up in cases to do with real property, they are often simply called ‘land’. They are ‘incorporeal hereditaments’ (literally, property without body) and are well glossed from the English and Welsh point of view in Halsbury’s Laws of England, vol viii, title Copyholds, which is available in most solicitors’ offices or central reference library. Manors cover an immutable area of land and may include rights over and under that land, such as rights to exploit minerals under the soil, manorial waste, commons and greens. While it has always been the case that manorial rights can sometimes have a high value, this is rare because the rights are frequently unknown and unresearched (or are just not commercial). There is no value in owning mineral rights if there are no commercially exploitable minerals, such as granite or aggregate, and purchasers should not expect a manorial Eldorado. If such benefits were routine, then asking prices by agents would be considerably higher to reflect this. -

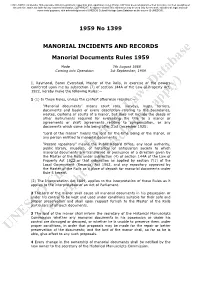

Manorial Documents Rules 1959

DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). 1959 No 1399 MANORIAL INCIDENTS AND RECORDS Manorial Documents Rules 1959 Made 7th August 1959 Coming into Operation 1st September, 1959 I, Raymond, Baron Evershed, Master of the Rolls, in exercise of the powers conferred upon me by subsection (7) of section 144A of the Law of Property Act, 1922, hereby make the following Rules:— 1 (1) In these Rules, unless the context otherwise requires:— “Manorial documents” means court rolls, surveys, maps, terriers, documents and books of every description relating to the boundaries, wastes, customs or courts of a manor, but does not include the deeds or other instruments required for evidencing the title to a manor or agreements or draft agreements relating to compensation, or any documents which came into being after 31st December 1925; “Lord of the manor” means the lord for the time being of the manor, or any person entitled to manorial documents; “Record repository” means the Public Record Office, any local authority, public library, museum, or historical or antiquarian society to which manorial documents are transferred in pursuance of a direction given by the Master of the Rolls under subsection (4) of section 144A of the Law of Property Act 1922 or that subsection as applied by section 7(1) of the Local Government (Records) Act 1962, and any repository approved by the Master of the Rolls as a place of deposit for manorial documents under Rule 5 hereof. -

The Lands of the Scottish Kings in England

THE LANDS OF THE SCOTTISH KINGS IN ENGLAND THE HONOUR OF HUNTINGDON THE LIBERTY OF TYNDALE AND THE HONOUR OF PENRITH BY MARGARET F. MOORE, M.A. (EDINBURGH) (CARNLGIKFELLOW IN PALEOGRAPHY AND EARLY ECONOMIC RIITORY) INTRODUCTION BY P. HUME BROWN, M.A., LL.D., Fraser Profcsaor of Ancient (Scottish) History and Palieography in the University of Edinburgh, and Historiographer- Royal for Scotland LONDON : GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD- RUSKIN HOUSE, MUSEUM STREET, W.C* CONTENTS PREFACE - - - - - --- - - vii CHAPTERI PAGE THE HISTORY OF THE HONOURS AND LIBERTY - - I CHAPTERI1 THE MEDIRVAL ASPECT OF THE LANDS - - - - 13 CHAPTERI11 THE FEUDAL HISTORY OF THE HOLDINGS - - - 29 CHAPTERIV THE MANORIAL FRANCHISES - - - - - - 48 CHAPTERV THE MANORIAL ECONOMY - ----- 67 CHAPTER VI LOCAL CHURCH HISTORY -..-- - 94 CHAPTERVII STATE OF SOCIETY ---- - 109 MANORIAL ECONOMY OF THE MANOR OF MARKET OVERTON IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY --- - 130 PREFACE THIs was completed during the tenure of a Carnegie Research Fellowship and has been published by aid of a grant from the Carnegie Trust. The subject of research, connected as it is with Scottish history, is one which appeals naturally to a Scottish student of English manorial history; for although it is well known that the Scottish kings held certain lands in England during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries little attention has been given to the details of these holdings. The personal association of David I and his heirs and of the ill-fated John Balliol with the Honour of Huntingdon, the Liberty of Tyndale and the Honour of Penrith is usually regarded as an incident of feudal tenure, and the sojourn of the Scottish kings on English soil has left no records other than the allowances and establish- ments of the royal household. -

19 Medieval Family History

A short guide to medieval family history Tracing your family history before the mid 16th century is a challenge. There are no parish registers before 1538 (and many do not even go back that far). However, there are other sources which can help you. With a bit of lateral thinking and some luck, you may be able to find earlier generations. There are some barriers to using original documents, but many are not as problematic as they seem at first. Many documents are in Latin. This was the official legal language until 1733. However, most follow a standard form. Once you are familiar with this, it is relatively easy to pick out the important names, dates and places. Early hand writing can seem difficult to read. Most people wrote in a fairly standard hand. Once you are familiar with the standard letter forms, it does become slightly easier. Some early documents are very fragile. It may be impossible for you to look at some items as this would cause irreparable damage to them. However, the descriptions of documents in catalogues are usually quite lengthy. They can give you some information without the need for seeing the document itself. You may find that many useful sources are not here at Shropshire Archives. Your ancestors may appear in some of the national sources which are held at The National Archives. The National Archives does have a very useful web-site at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk with lots of information about the types of records they hold. We have printed copies of some sources (see later).