Seeing the Lianas in the Trees: Woody Vines of the Temperate Zone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region

$10 $10 PB1785 PB1785 Invasive Weeds Invasive Weeds of the of the Appalachian Appalachian Region Region i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………...i How to use this guide…………………………………ii IPM decision aid………………………………………..1 Invasive weeds Grasses …………………………………………..5 Broadleaves…………………………………….18 Vines………………………………………………35 Shrubs/trees……………………………………48 Parasitic plants………………………………..70 Herbicide chart………………………………………….72 Bibliography……………………………………………..73 Index………………………………………………………..76 AUTHORS Rebecca M. Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, The University of Tennessee Gregory R. Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Specialist for Invasive Weeds, The University of Tennessee Robert J. Richardson, Assistant Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, North Caro- lina State University G. Neil Rhodes, Jr., Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, The University of Ten- nessee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank all the individuals and organizations who have contributed their time, advice, financial support, and photos to the crea- tion of this guide. We would like to specifically thank the USDA, CSREES, and The Southern Region IPM Center for their extensive support of this pro- ject. COVER PHOTO CREDITS ii 1. Wavyleaf basketgrass - Geoffery Mason 2. Bamboo - Shawn Askew 3. Giant hogweed - Antonio DiTommaso 4. Japanese barberry - Leslie Merhoff 5. Mimosa - Becky Koepke-Hill 6. Periwinkle - Dan Tenaglia 7. Porcelainberry - Randy Prostak 8. Cogongrass - James Miller 9. Kudzu - Shawn Askew Photo credit note: Numbers in parenthesis following photo captions refer to the num- bered photographer list on the back cover. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Tabs: Blank tabs can be found at the top of each page. These can be custom- ized with pen or marker to best suit your method of organization. Examples: Infestation present On bordering land No concern Uncontrolled Treatment initiated Controlled Large infestation Medium infestation Small infestation Control Methods: Each mechanical control method is represented by an icon. -

Invasive Plants of the Southeast Flyer

13 15 5 1 19 10 6 18 8 7 T o p 2 0 I n v a s i v e S p e c i e s 1. Chinese Privet, Ligustrum sinense 2. Nepalese Browntop, Microstegium vimineum 3. Autumn Olive, Elaeagnus umbellata 4. Chinese Wisteria, Wisteria sinensis & Japanese Wisteria, W. floribunda 5. Mimosa, Albizia julibrissin 6. Japanese Honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica 7. Amur Honeysuckle, Lonicera maackii 8. Multiflora Rose, Rosa multiflora 9. Hydrilla, Hydrilla verticillata 10. Kudzu, Pueraria montana 11. Golden Bamboo, Phyllostachys aurea 12. Oriental Bittersweet, Celastrus orbiculatus 13. English Ivy, Hedera helix 14. Tree-of-Heaven, Ailanthus altissima 15. Chinese Tallow, Sapium sebiferum 16. Chinese Princess Tree, Paulownia tomentosa 17. Japanese Knotweed, Polygonum cuspidatum 18. Silvergrass, Miscanthus sinensis 19. Thorny Olive, Elaeagnus pungens 20. Nandina, Nandina domestica The State Botanical Garden of Georgia and The Georgia Plant Conservation A l l i a n c e d e f i n i t i o n s you can help n a t i ve Avoid disturbing natural areas, including clearing of native vegetation. A native species is one that occurs in a particular region, ecosystem or habitat Know your plants. Find out if plants you without direct or indirect human action. grow have invasive tendencies. Do not use invasive species in landscaping, n o n - n a t i ve restoration, or for erosion control; use (alien, exotic, foreign, introduced, plants known not to be invasive in your area. non-indigenous) A species that occurs artificially in locations Control invasive plants on your land by beyond its known historical removing or managing them to prevent natural range. -

Heterospory: the Most Iterative Key Innovation in the Evolutionary History of the Plant Kingdom

Biol. Rej\ (1994). 69, l>p. 345-417 345 Printeii in GrenI Britain HETEROSPORY: THE MOST ITERATIVE KEY INNOVATION IN THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE PLANT KINGDOM BY RICHARD M. BATEMAN' AND WILLIAM A. DiMlCHELE' ' Departments of Earth and Plant Sciences, Oxford University, Parks Road, Oxford OXi 3P/?, U.K. {Present addresses: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburiih, Inverleith Rojv, Edinburgh, EIIT, SLR ; Department of Geology, Royal Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EHi ijfF) '" Department of Paleohiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC^zo^bo, U.S.A. CONTENTS I. Introduction: the nature of hf^terospon' ......... 345 U. Generalized life history of a homosporous polysporangiophyle: the basis for evolutionary excursions into hetcrospory ............ 348 III, Detection of hcterospory in fossils. .......... 352 (1) The need to extrapolate from sporophyte to gametophyte ..... 352 (2) Spatial criteria and the physiological control of heterospory ..... 351; IV. Iterative evolution of heterospory ........... ^dj V. Inter-cladc comparison of levels of heterospory 374 (1) Zosterophyllopsida 374 (2) Lycopsida 374 (3) Sphenopsida . 377 (4) PtiTopsida 378 (5) f^rogymnospermopsida ............ 380 (6) Gymnospermopsida (including Angiospermales) . 384 (7) Summary: patterns of character acquisition ....... 386 VI. Physiological control of hetcrosporic phenomena ........ 390 VII. How the sporophyte progressively gained control over the gametophyte: a 'just-so' story 391 (1) Introduction: evolutionary antagonism between sporophyte and gametophyte 391 (2) Homosporous systems ............ 394 (3) Heterosporous systems ............ 39(1 (4) Total sporophytic control: seed habit 401 VIII. Summary .... ... 404 IX. .•Acknowledgements 407 X. References 407 I. I.NIRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF HETEROSPORY 'Heterospory' sensu lato has long been one of the most popular re\ie\v topics in organismal botany. -

Botany for Gardeners Offers a Clear Explanation of How Plants Grow

BotGar_Cover (5-8-2004) 11/8/04 11:18 AM Page 1 $19.95/ £14.99 GARDENING & HORTICULTURE/Reference Botany for Gardeners offers a clear explanation of how plants grow. • What happens inside a seed after it is planted? Botany for Gardeners Botany • How are plants structured? • How do plants adapt to their environment? • How is water transported from soil to leaves? • Why are minerals, air, and light important for healthy plant growth? • How do plants reproduce? The answers to these and other questions about complex plant processes, written in everyday language, allow gardeners and horticulturists to understand plants “from the plant’s point of view.” A bestseller since its debut in 1990, Botany for Gardeners has now been expanded and updated, and includes an appendix on plant taxonomy and a comprehensive index. Twodozen new photos and illustrations Botany for Gardeners make this new edition even more attractive than its predecessor. REVISED EDITION Brian Capon received a ph.d. in botany Brian Capon from the University of Chicago and was for thirty years professor of botany at California State University, Los Angeles. He is the author of Plant Survival: Adapting to a Hostile Brian World, also published by Timber Press. Author photo by Dan Terwilliger. Capon For details on other Timber Press books or to receive our catalog, please visit our Web site, www.timberpress.com. In the United States and Canada you may also reach us at 1-800-327-5680, and in the United Kingdom at [email protected]. ISBN 0-88192-655-8 ISBN 0-88192-655-8 90000 TIMBER PRESS 0 08819 26558 0 9 780881 926552 UPC EAN 001-033_Botany 11/8/04 11:20 AM Page 1 Botany for Gardeners 001-033_Botany 11/8/04 11:21 AM Page 2 001-033_Botany 11/8/04 11:21 AM Page 3 Botany for Gardeners Revised Edition Written and Illustrated by BRIAN CAPON TIMBER PRESS Portland * Cambridge 001-033_Botany 11/8/04 11:21 AM Page 4 Cover photographs by the author. -

Model Calibration)

The impact of lianas on radiative transfer and albedo of tropical forests A modelling study In a nutshell Lianas are visible from space! Liana-free canopy Liana-infested tree Waite et al., Journal of applied ecology, 2019 Lianas are visible from space → ← Forest spectrum is impacted by lianas Liana-free canopy Liana-infested tree Waite et al., Journal of applied ecology, 2019 Chris Chandler credits The study We used process-based models of the leaf (PROSPECT) and the canopy (ED-RTM) coupled to a bayesian parameter assimilation technique to reproduce forest canopy spectra as affected by lianas and derive the canopy changes due to liana-infestation. To do so, we first compiled all existing data of liana leaf spectrum and all published spectra of canopy with contrasted levels of liana infestation. We calibrated liana (and co-occurring tree) leaf traits to reproduce their respective leaf spectra and feed that information into the canopy model. These models can now serve to predict the impact of liana on light transmission in dense canopies, on the Energy budget of infested tropical forests and more generally on their functioning. Results (calibration) Leaf spectrum Canopy spectrum Results (traits) ● Liana leaves differ from tree leaves by many aspects (pigment content is lower, leaves are “cheaper” and contain more water) ● Liana infest more in leaves than trees, liana canopies are more clumped, and their leaves are more horizontal. Example of application vs PAR (+0.01) VNIR (+0.043) SNIR (+0.035) NIR (+0.04) SW (+0.033) changes Energy budget -

Porcelain Berry

FACT SHEET: PORCELAIN-BERRY Porcelain-berry Ampelopsis brevipedunculata (Maxim.) Trautv. Grape family (Vitaceae) NATIVE RANGE Northeast Asia - China, Korea, Japan, and Russian Far East DESCRIPTION Porcelain-berry is a deciduous, woody, perennial vine. It twines with the help of non-adhesive tendrils that occur opposite the leaves and closely resembles native grapes in the genus Vitis. The stem pith of porcelain-berry is white (grape is brown) and continuous across the nodes (grape is not), the bark has lenticels (grape does not), and the bark does not peel (grape bark peels or shreds). The Ieaves are alternate, broadly ovate with a heart-shaped base, palmately 3-5 lobed or more deeply dissected, and have coarsely toothed margins. The inconspicuous, greenish-white flowers with "free" petals occur in cymes opposite the leaves from June through August (in contrast to grape species that have flowers with petals that touch at tips and occur in panicles. The fruits appear in September-October and are colorful, changing from pale lilac, to green, to a bright blue. Porcelain-berry is often confused with species of grape (Vitis) and may be confused with several native species of Ampelopsis -- Ampelopsis arborea and Ampelopsis cordata. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Porcelain-berry is a vigorous invader of open and wooded habitats. It grows and spreads quickly in areas with high to moderate light. As it spreads, it climbs over shrubs and other vegetation, shading out native plants and consuming habitat. DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES Porcelain-berry is found from New England to North Carolina and west to Michigan (USDA Plants) and is reported to be invasive in twelve states in the Northeast: Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington D.C., West Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

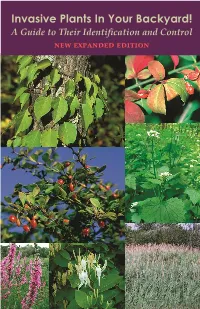

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

Cop16 Prop. 65

Original language: French CoP16 Prop. 65 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Sixteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok (Thailand), 3-14 March 2013 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Include the species Adenia firingalavensis in CITES Appendix II, in accordance with Article II, paragraph 2(a) of the Convention and Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP13), Annex 2 a, paragraph A. B. Proponent Madagascar* C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Dicotyledones 1.2 Order: Violales 1.3 Family: Passifloraceae 1.4 Genus, species, including author and year: Adenia firingalavensis (Drake ex Jum.) Harms 1.5 Scientific synonyms: Ophiocaulon firingalavense Drake ex Jum. (1903) 1.6 Common names: English: Bottle liana Malagasy: holabe (Sakalava), holaboay, Kajabaka (North of Madagascar), lazamaitso (Tuléar), Lokoranga (Morondava), Olabory, Trangahy. Vietnamese: Ga loi lam mao den 1.7 Code numbers: 2. Overview Adenia firingalavensis is a climbing shrub that often has swollen roots and stem bases. Its leaves are deciduous and usually appear after the plant has flowered. This endemic species to Madagascar is collected from the wild and has become rare. However, it is not yet protected by the CITES Convention. The present document suggests that the species Adenia firingalavensis meets the criteria for inclusion in CITES Appendix II in accordance with Article II, paragraph 2(a) of the Convention and Resolution * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Landscape Vines for Southern Arizona Peter L

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AZ1606 October 2013 LANDSCAPE VINES FOR SOUTHERN ARIZONA Peter L. Warren The reasons for using vines in the landscape are many and be tied with plastic tape or plastic covered wire. For heavy vines, varied. First of all, southern Arizona’s bright sunshine and use galvanized wire run through a short section of garden hose warm temperatures make them a practical means of climate to protect the stem. control. Climbing over an arbor, vines give quick shade for If a vine is to be grown against a wall that may someday need patios and other outdoor living spaces. Planted beside a house painting or repairs, the vine should be trained on a hinged trellis. wall or window, vines offer a curtain of greenery, keeping Secure the trellis at the top so that it can be detached and laid temperatures cooler inside. In exposed situations vines provide down and then tilted back into place after the work is completed. wind protection and reduce dust, sun glare, and reflected heat. Leave a space of several inches between the trellis and the wall. Vines add a vertical dimension to the desert landscape that is difficult to achieve with any other kind of plant. Vines can Self-climbing Vines – Masonry serve as a narrow space divider, a barrier, or a privacy screen. Some vines attach themselves to rough surfaces such as brick, Some vines also make good ground covers for steep banks, concrete, and stone by means of aerial rootlets or tendrils tipped driveway cuts, and planting beds too narrow for shrubs. -

A List of Plants Recommended for Snow Creek Landscaping Projects

A List of Plants Recommended for Snow Creek Landscaping Projects This is intended to be a partial list of regional native plants that have proven to be reliably hardy in the Asheville area and conform to Snow Creek’s mission of developing sustainable landscapes. Plants with * in column D are thought to be resistant to deer browse. Please note that as the deer population increases and natural food supplies decrease deer may begin to feed off of plants included in this list. Column W ranks the water needs for each species from 1 to 3 with 3 being the highest moisture requirement. Newly installed plants require more water than usual. All plants have specific site requirements so please consult a reliable text for more detailed information about cultural requirements. The estimated height and spread of plants at maturity is given in feet. SHADE TREES: SPECIES CULTIVARS HT/SP FORM QUALITIES PROBLEMS D W Acer rubrum ‘Autumn 55/45 Broadly Can withstand wet or Shallow rooted, will * Red Maple Flame’ 60/50 ovate compacted soil, good not withstand high pH. 2 ‘Oct. Glory’ 50/30 Broadly red fall color, fast ‘Bowhall’ 60/50 ovate growing ‘Red Sunset’ Broadly Many others ovate Broadly ovate Acer x ‘Freemanii’ ‘Armstrong’ 60/25 Columnar Many of the same Somewhat shallow * 2 Hybrid Maple ‘Autumn 65/50 Ovate qualities as Red rooted Blaze’ 70/35 Ovate Maple but faster Not tolerant of high ‘Scarlet pH. Sentinel’ Acer saccharum ‘Gr. Mountain’ 70/40 Upright Excellent fall color, Requires a moist, * Sugar Maple ‘Legacy’ oval summer shade, fertile soil. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

![Fifay 15, 1884] NATURE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2572/fifay-15-1884-nature-992572.webp)

Fifay 15, 1884] NATURE

fifay 15, 1884] NATURE the position of some of the Cretaceous deposits and the marked Piedmont. By t heir means great piles of broken rock must h~ve mineral differences between these and the Jurassic seem to indi been transported into the lowlands ; hut did they greatly modify cate disturbances dnring some part of the ;-.:- eocomian, but I am the peaks, deepen the v:1lleys, or excavate the lake basms ? My not aware of any marked trace of these over the central and reply would be, '' T o no very material extent. " I r egard (he western areas. The mountain-making of th e existing Alps elates o-Jacier as the fil e rather than as the clusel of nature. The Alpme from the later part of the Eocene. Beds of about the age of our Jakes appear to be more easily explained-as the Dead Sea can Bracklesham series now cap such summits as the Diablerets, or only be explained-as the result of subsidence along zones r<;mghly help to form the mountain masses near the T iid i, rising in the parallel with the Alpine ranges, athwart the general d1 rectt0ns of Bifertenstock to a height of rr, 300 feet above the sea. Still valleys which already existed and had been in the main com there are signs that the sea was then shallowing a nd the epoch pleted in pre-Glacial times. To produce these lake basins we of earth movements commencing. The Eocene deposits of Swit should require earth movements o n n o greater scale t han have cerlancl include terrestrial and fluviatile as well as marine taken place in our own country since the furthermost extension remains.