Study Tour Northumberland and Cumbria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Richard Pears, ‘Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 117–134 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 BUILDING HOWICK HALL, NOrthUMBERLAND, 1779–87 RICHARD PEARS Howick Hall was designed by the architect William owick Hall, Northumberland, is a substantial Newton of Newcastle upon Tyne (1730–98) for Sir Hmansion of the 1780s, the former home of Henry Grey, Bt., to replace a medieval tower-house. the Charles, second Earl Grey (1764–1845), Prime Newton made several designs for the new house, Minister at the time of the 1832 Reform Act. (Fig. 1) drawing upon recent work in north-east England The house replaced a medieval tower and was by James Paine, before arriving at the final design designed by the Newcastle architect William Newton in collaboration with his client. The new house (1730–98) for the Earl’s bachelor uncle Sir Henry incorporated plasterwork by Joseph Rose & Co. The Grey (1733–1808), who took a keen interest in his earlier designs for the new house are published here nephew’s education and emergence as a politician. for the first time, whilst the detailed accounts kept by It was built 1781 to 1788, remodelled on the north Newton reveal the logistical, artisanal and domestic side to make a new entrance in 1809, but the interior requirements of country house construction in the last was devastated in a fire in 1926. Sir Herbert Baker quarter of the eighteenth century. radically remodelled the surviving structure from Fig. 1. Howick Hall, Northumberland, by William Newton, 1781–89. South front and pavilions. -

Influence of the Spatial Pressure Distribution of Breaking Wave

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Influence of the Spatial Pressure Distribution of Breaking Wave Loading on the Dynamic Response of Wolf Rock Lighthouse Darshana T. Dassanayake 1,2,* , Alessandro Antonini 3 , Athanasios Pappas 4, Alison Raby 2 , James Mark William Brownjohn 5 and Dina D’Ayala 4 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Technology, Faculty of Technology, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Pitipana 10206, Sri Lanka 2 School of Engineering, Computing and Mathematics, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, Stevinweg 1, 2628 CN Delft, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Science, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (D.D.) 5 College of Engineering, Mathematics and Physical Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4QF, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The survivability analysis of offshore rock lighthouses requires several assumptions of the pressure distribution due to the breaking wave loading (Raby et al. (2019), Antonini et al. (2019). Due to the peculiar bathymetries and topographies of rock pinnacles, there is no dedicated formula to properly quantify the loads induced by the breaking waves on offshore rock lighthouses. Wienke’s formula (Wienke and Oumeraci (2005) was used in this study to estimate the loads, even though it was not derived for breaking waves on offshore rock lighthouses, but rather for the breaking wave loading on offshore monopiles. -

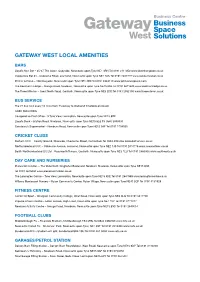

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

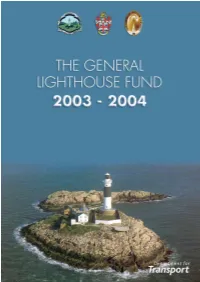

The General Lighthouse Fund 2003-2004 HC

CONTENTS Foreword to the accounts 1 Performance Indicators for the General Lighthouse Authorities 7 Constitutions of the General Lighthouse Authorities and their board members 10 Statement of the responsibilities of the General Lighthouse Authorities’ boards, Secretary of State for Transport and the Accounting Officer 13 Statement of Internal control 14 Certificate of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament 16 Income and expenditure account 18 Balance sheet 19 Cash flow statement 20 Notes to the accounts 22 Five year summary 40 Appendix 1 41 Appendix 2 44 iii FOREWORD TO THE ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 March 2004 The report and accounts of the General Lighthouse Fund (the Fund) are prepared pursuant to Section 211(5) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995. Accounting for the Fund The Companies Act 1985 does not apply to all public bodies but the principles that underlie the Act’s accounting and disclosure requirements are of general application: their purpose is to give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the body concerned. The Government therefore has decided that the accounts of public bodies should be prepared in a way that conforms as closely as possible with the Act’s requirements and also complies with Accounting Standards where applicable. The accounts are prepared in accordance with accounts directions issued by the Secretary of State for Transport. The Fund’s accounts consolidate the General Lighthouse Authorities’ (GLAs) accounts and comply as appropriate with this policy. The notes to the Bishop Rock Lighthouse accounts contain further information. Section 211(5) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 requires the Secretary of State to lay the Fund’s accounts before Parliament. -

THE TRINITY HOUSE LUNDY ARCHIVE: a PAPER in MEMORY of the LIGHTHOUSE KEEPERS of LUNDY by R.W.E

Rep. Lundy Field SOc. 44 THE TRINITY HOUSE LUNDY ARCHIVE: A PAPER IN MEMORY OF THE LIGHTHOUSE KEEPERS OF LUNDY By R.W.E. Farrah 4, Railway Cottages, Long Marton, Appleby, Cumbria CAI6 6BY INTRODUCTION The approaches to the Bristol Channel along the northern coast of Cornwall and Devon offer very little shelter for the seafarer during severe weather conditions. Lundy, however, situated at the mouth of the Channel central to the busy sea lanes, is one exception and has provided an important refuge on the leeward side of the island throughout the historic period. Before the navigational aids of the lighthouses were built, the island must also have proved hostile to the mariner, especially during hours of darkness and poor visibility. The number of shipwrecks and marine disasters around the island bear testimony to this. The dangers were considerable; although the tidal streams to the west of Lundy are moderate, they are strong around the island. There are several bad races, to the north-east (The White Horses), the north-west (T)1e Hen and Chickens) and to the south-east. There are also overfalls over the north-west bank. Some appreciation of the dangers the island posed can be seen from the statistics issued by a Royal Commission of 1859 who were reporting on a harbour refuge scheme. They noted that: "out of 173 wrecks in the Bristol Channel in 1856-57, 97 received their damage and 44 lives were lost east of Lundy; while 76 vessels were lost or damaged and 58 lives sacrificed west of Lundy, thus showing the island to be nearly in the centre of the dangerous parts" (quoted in Langham A and M, 1984,92). -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland -

The Corporation Trinity House Deptford Strond

THE CORPORATION T R I N I TY H O U S E DEPTFORD STROND fl 9192111 0 11 3 E G I N ’h S T O I Y 8 N T T S u C I O N S . J p Q , j i , ; f P R I N TE D ( F O R P R ] V A TE D I S TR I B U TI O N ) B Y N R O W W SMIT H E BBS P O ST E R T O E R H IL L . , 5, , M D C I I I I I I I I I TO H I S R O YAL H I GH N ESS T H E U E O F E I N U R GH K . G. K. T. D K D B , , , aste: of fi s fi nr or ti of O rinit 0 11 3 2 w g g a nu g £ , T H E F O L L O W I N A AR E G P GES , BY E R I I O N P M SS , O R E P E U LY I CA M ST S CTF L DED TED , I H T H E L O YAL U Y W T D T , P R F D E E M O O U N E ST , A N D S P E C I AL C O N GR AT U L AT I O N F T H E I R O CO MP LE . -

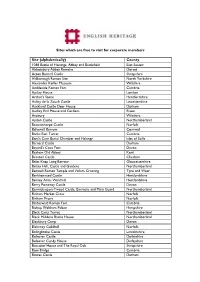

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Festival of the North East Begins Win an English Heritage Family Pass

Northumberland News issue 25 Summer 2013 www.northumberland.gov.uk | Phone 0845 600 6400 Festival of the North East begins LOVE Northumberland Awards Win an English Heritage family pass Plus Markets and summer shopping | Bin collection timetables online | What’s on 6 20 9 21 25 Northumberland In this issue: News 4 Festival of the North East events 9 New library and customer Now available online, by email or in print. information centre Northumberland News is a quarterly magazine 11 Apprenticeships – 100 day packed with features and news articles written challenge specifically for county residents. 14 New county councillors Published in December, March, June and September it is distributed free of charge by 19 Engineering award for new bridge Northumberland County Council. Every effort is made to ensure that all information is accurate at 27 Superfast broadband for all the time of publication. Facebook at: If you would like to receive www.northumberland.gov.uk/facebook Northumberland News in large print, Twitter at: Braille, audio, or in another format or www.northumberland.gov.uk/twitter language please contact us. YouTube at: www.northumberland.gov.uk/youtube Telephone: 0845 600 6400 Front cover: BBC Look North’s Carol Malia with Type Talk: 18001 0845 600 6400 Nicola Wardle (left) from Northumberland County Council, launching the LOVE Northumberland Email: [email protected] Awards. Full story page seven. 2 www.northumberland.gov.uk | Phone 0845 600 6400 Welcome for the huge range of services in We hope you find something Northumberland is included on of interest in the summer pages 14 and 15. -

Blue Plaque Sites

Cullercoats blue plaques Fishermans Lookout Opp’ Window Court Flats. Tyne and Wear County Council 1986. Built in 1879 on the site of a traditional fishermans lookout, to house the Cullercoats Volunteer Life Brigade. A pre-existing clock tower was incorporated in the design. Now used as a community centre. Metropolitan Borough of North Tyneside. Winslow Court former site of the Bay Hotel in Cullercoats North Tyneside Council. Winslow Homer, American artist stayed here when it was the Hudleston Arms between 1881 and 1882 when he lived and worked in Cullercoats. North Shields blue plaques New Quay, North Shields Tyne and Wear County 1986 Former Sailors Home, built by the 4th Duke of Northumberland in 1854-6 to accommodate 80 visiting seamen. Architect Benjamin Green. Metropolitan Borough of North Tyneside. Howard Street, North Shields Tyne and Wear County Council 1986. Maritime Chambers built in 1806-7 as a subscription library for Tynemouth Literary and Philosophical Society. Occupied 1895-1980 by Stag Line Ltd. One of Tyneside's oldest family owned shipping companies. The building still bears the stag emblem, Metropolitan Borough of North Tyneside. Old High Light, Trinity Buildings, North Shields Tyne and Wear County Council 1986. Since 1536 Trinity House, Newcastle has built several leading lights in North Shields. This one was constructed in 1727. Following changes in the river channel it was replaced in 1807 by the new High Light. Metropolitan Borough of North Tyneside. New Low Light, Fishquay, North Shields Port of Tyne Authority. The new Lighthouse and Keeper's house were erected in 1808-10 by the Master and Brethren of Trinity House, Newcastle, to replace the Old Low Light. -

William Newton (1730-1798) and the Development Of

William Newton (1730-1798) and the Development of the Architectural Profession in North-East England Richard Pears A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University April 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the emergence of the professional architect in the provinces of eighteenth-century Britain, drawing upon new research into the career of William Newton (1730-1798) of Newcastle upon Tyne. Section I assesses the growth of professionalism, identifying the criteria that distinguished professions from other occupations and their presence in architectural practitioners. It contrasts historians’ emphasis upon innovative designs by artist-architects, such as Sir John Vanbrugh and Robert Adam, with their absence from the realisation of their designs. Clients had to employ capable building craftsmen to supervise construction and this was an opportunity for an alternative practitioner to emerge, the builder-architect exemplified by Newton, offering clients proven practical experience, frequent supervision, peer group recommendation and financial responsibility. Patronage networks were a critical factor in securing commissions for provincial builder-architects, demonstrated here by a reconstruction of Newton’s connections to the north-east élite. Section II reveals that the coal-based north-east economy sustained architectural expenditure, despite national fluctuations. A major proposal of this thesis is that, contrary to Borsay’s theory of an ‘English urban renaissance’, north-east towns showed continuity and slow development. Instead, expenditure was focused upon élite social spaces and industrial infrastructure, and by the extensive repurposing of the hinterlands around towns. This latter development constituted a ‘rural renaissance’ as commercial wealth created country estates for controlled access to social pursuits by élite families. -

Safe Passage We Talk to One of Our Boatswains About How We’Re Working Hard to Keep Our Seas Safe and Protect Seafarers Spring 2017 | Issue 26

The Trinity House journal | Spring 2017 | Issue 26 Safe passage We talk to one of our Boatswains about how we’re working hard to keep our seas safe and protect seafarers Spring 2017 | Issue 26 1 Welcome from Deputy Master, Captain Ian McNaught 2-4 Six month review 16 5 News in brief 34 6 Coming events 7 A sea change in awareness 8-9 Appointments 10-18 Engineering review 38 19 IALA update 22 20-21 The LED revolution 22 30 Running a tight ship 23 Wake up call 24-27 Charity update 28-29 How the Merchant Navy opens doors Welcome to your new Flash journal 30-33 Partner profile: IALA I would like to welcome all readers to your new-look Flash journal, the latest iteration of a publication that began in 1958 and has since seen a great many evolutions, both 34-35 significant and minor. Adapting to climate change Deputy Master Sir Gerald Curteis’ foreword for the inaugural 1958 issue of Flash 36 stated that the object of the magazine was ‘to bring us more together and to remind us that we belong to one service.’ With that cohesive spirit in mind, this new evolution of Book reviews our house journal will renew its focus on what makes Trinity House and our mission 37 so important: the people who work for us, the people who work with us and the Former lightvessel finds mariners we serve. I wish to thank—as always—the many people who contributed to putting this new purpose journal together. 38 Photography competition Neil Jones, Editor Trinity House, The Quay, Harwich CO12 3JW 39-45 01255 245155 A-Z of Trinity House [email protected] Captain Ian McNaught Deputy Master Emergent technologies, integrated planning and better awareness of mariner fatigue are all important elements in safeguarding seafarers and shipping he ongoing need for efficiencies—properly balanced against the need for the utmost reliability—means Tthat our work as a General Lighthouse Authority demands a high familiarity with new technology.