William Newton (1730-1798) and the Development Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Richard Pears, ‘Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 117–134 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 BUILDING HOWICK HALL, NOrthUMBERLAND, 1779–87 RICHARD PEARS Howick Hall was designed by the architect William owick Hall, Northumberland, is a substantial Newton of Newcastle upon Tyne (1730–98) for Sir Hmansion of the 1780s, the former home of Henry Grey, Bt., to replace a medieval tower-house. the Charles, second Earl Grey (1764–1845), Prime Newton made several designs for the new house, Minister at the time of the 1832 Reform Act. (Fig. 1) drawing upon recent work in north-east England The house replaced a medieval tower and was by James Paine, before arriving at the final design designed by the Newcastle architect William Newton in collaboration with his client. The new house (1730–98) for the Earl’s bachelor uncle Sir Henry incorporated plasterwork by Joseph Rose & Co. The Grey (1733–1808), who took a keen interest in his earlier designs for the new house are published here nephew’s education and emergence as a politician. for the first time, whilst the detailed accounts kept by It was built 1781 to 1788, remodelled on the north Newton reveal the logistical, artisanal and domestic side to make a new entrance in 1809, but the interior requirements of country house construction in the last was devastated in a fire in 1926. Sir Herbert Baker quarter of the eighteenth century. radically remodelled the surviving structure from Fig. 1. Howick Hall, Northumberland, by William Newton, 1781–89. South front and pavilions. -

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments

Constituency Ward District Reference Polling Place Returning Officer Comments Central Arthurs Hill A01 A1 Stanton Street Community Lounge, Stanton Street, NE4 5LH Propose no change to polling district or polling place Moorside Primary School, Beaconsfield Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A02 A2 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 5AW Central Arthurs Hill A03 A3 Spital Tongues Community Centre, Morpeth Street, NE2 4AS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Westgate Baptist Church, 366 Westgate Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE4 Central Arthurs Hill A04 A4 Propose no change to polling district or polling place 6NX Proposed no change to polling district, however it is recommended that the Benwell and Broadwood Primary School Denton Burn Library, 713 West Road, Newcastle use of Broadwood Primary School is discontinued due to safeguarding Central B01 B1 Scotswood upon Tyne, NE15 7QQ issues and it is proposed to use Denton Burn Library instead. This building was used to good effect for the PCC elections earlier this year. Benwell and Central B02 B2 Denton Burn Methodist Church, 615-621 West Road, NE15 7ER Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B03 B3 Broadmead Way Community Church, 90 Broadmead Way, NE15 6TS Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Central B04 B4 Sunnybank Centre, 14 Sunnybank Avenue, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE15 6SD Propose no change to polling district or polling place Scotswood Benwell and Atkinson -

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020

Know Your Councillors 2019 — 2020 Arthur’s Hill Benwell & Scotswood Blakelaw Byker Callerton & Throckley Castle Chapel Dene & South Gosforth Denton & Westerhope Ali Avaei Lord Beecham DCL DL Oskar Avery George Allison Ian Donaldson Sandra Davison Henry Gallagher Nick Forbes C/o Members Services Simon Barnes 39 The Drive C/o Members Services 113 Allendale Road Clovelly, Walbottle Road 11 Kelso Close 868 Shields Road c/o Leaders Office Newcastle upon Tyne C/o Members Services Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne Walbottle Chapel Park Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8QH Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 4AJ NE1 8QH NE6 2SY Newcastle upon Tyne Newcastle upon Tyne NE6 4QP NE1 8QH 0191 274 0627 NE1 8QH 0191 285 1888 07554 431 867 0191 265 8995 NE15 8HY NE5 1TR 0191 276 0819 0191 211 5151 07765 256 319 07535 291 334 07768 868 530 Labour Labour 07702 387 259 07946 236 314 07947 655 396 Labour Liberal Democrat Labour Labour Newcastle First Independent Liberal Democrat [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Marc Donnelly Veronica Dunn Melissa Davis Joanne Kingsland Rob Higgins Nora Casey Stephen Fairlie Aidan King 17 Ladybank Karen Robinson 18 Merchants Wharf 78a Wheatfield Road 34 Valley View 11 Highwood Road C/o Members Services 24 Hawthorn Street 15 Hazelwood Road Newcastle upon Tyne 441 -

On-Street Disabled Bays

On-Street Disabled Bays Post Code of Days Hours Street Location restrictions restrictions Ward (not apply apply individual bay) Acorn Road (x2) • 1 x Outside Hardware shop North NE2 2DJ All All • 1 x Close to Jesmond junction with St. George’s Terrace Akenside Hill • Under Tyne NE1 3XP All All Westgate Bridge Back Shields Road • Near junction NE6 1XQ All All Byker with Flora Street Bath Lane • Near junction NE4 5SP All All Westgate with Stowell Street Benton Bank • Near junction South NE2 1HB All All with Jesmond Jesmond Road Benton Road Service Road (x2) • 2 x north of NE7 7DR All All Dene junction with Benton Road Benwell Lane (x2) • 1 x Near junction with NE15 Benwell & Rushie Avenue All All 6NG Scotswood • 1 x Near junction with Pendower Way Bigg Market • Near junction NE1 1UW All All Westgate with Pudding Chare Post Code of Days Hours Street Location restrictions restrictions Ward (not apply apply individual bay) Breamish Street • Near junction NE1 2DZ All All Ouseburn with Crawhall Road Brighton Grove (x3) • 2 – Opposite side of road to NE4 5NT All All Wingrove Cathedral • Near junction with Barrack Road Broad Chare 8.00am – • Near junction NE1 3HE All Ouseburn 6.30pm with Quayside Broomfield Road (x2) West • 2 x near NE3 4HH All All Gosforth junction with North Avenue Brunel Terrace • South of De NE4 7NL All All Elswick Grey Street Burdon Terrace South NE2 3AE All All • Outside Church Jesmond Cambridge Street • Opposite NE4 7HL All All Elswick junction with Mather Road Carliol Square (east section) NE1 6UF All All Westgate • Outside -

The London Gazette, November 20, 1860

4344 THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 20, 1860. relates to each of the parishes in or through which the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England, and the said intended railway and works will be made, in the occupation of the lessees of Tyne Main together with a copy of the said Gazette Notice, Colliery, with an outfall or offtake drift or water- will be deposired for public inspection with the course, extending from the said station to a p >int parish clerk of each such parish at his residence : immediately eastward of the said station ; on a and in the case of any extra-parochial place with rivulet or brook, in the chapelry of Heworth, in the parish clerk of some parish immediately ad- the parish of Jarrow, and which flows into the joining thereto. river Tyne, in the parish of St Nicholas aforesaid. Printed copies of the said intended Bill will, on A Pumping Station, with shafts, engines, and or before the 23rd day of December next, be de- other works, at or near a place called the B Pit, posited in the Private Bill Office of the House of at Hebburn Colliery, in the township of Helburn, Commons. in the parish of Jarrow, on land belonging to Dated this eighth day of November, one thou- Lieutenant-Colonel Ellison, and now in the occu- sand eight hundred and sixty. pation of the lessees of Hebburn Colliery, with an F. F. Jeyes} 22, Bedford-row, Solicitor for outfall or offtake drift or watercourse, extending the Bill. from the said station to the river Tyne aforesaid, at or near a point immediately west of the Staith, belonging to the said Hebburn Colliery. -

A1 in Northumberland: Morpeth to Ellingham Scheme Number

A1 in Northumberland: Morpeth to Ellingham Scheme Number: TR010059 6.42 Written Scheme of Investigation for an Archaeological Trial Trench Evaluation (Clean) for Change Request Rule 8(1)(c) Planning Act 2008 Infrastructure Planning (Examination Procedure) Rules 2010 March 2021 Infrastructure Planning Planning Act 2008 The Infrastructure Planning (Examination Procedure) Rules 2010 The A1 in Northumberland: Morpeth to Ellingham Development Consent Order 20[xx] Written Scheme of Investigation for an Archaeological Trial Trench Evaluation (Clean) for Change Request Rule Reference: 8(1)(c) Planning Inspectorate Scheme TR010059 Reference: Doc Reference: 6.42 Author: A1 in Northumberland: Morpeth to Ellingham Project Team, Highways England Version Date Status of Version Rev 1 March 2021 Deadline 4 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 SCHEME BACKGROUND 1 1.2 DETAILED SCHEME DESCRIPTION 2 1.3 CONSULTATION 3 2 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT BASELINE SUMMARY 5 2.1 SITE LOCATION 5 2.2 TOPOGRAPHY 5 2.3 GEOLOGY 5 2.4 ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL 5 3 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 12 4 METHODOLOGY 13 4.1 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS 13 4.2 FIELDWORK METHODOLOGY 14 4.3 HAND EXCAVATION 15 4.4 ARTEFACTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL SAMPLES 17 5 REPORTING 20 5.1 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS 20 5.2 REPORT CONTENT 20 5.3 PUBLICATION AND DISSEMINATION 21 6 ARCHIVE 23 6.1 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS 23 7 OPERATIONAL FACTORS 24 7.1 PROJECT TIMETABLE AND MONITORING ARRANGEMENTS 24 7.2 HEALTH AND SAFETY 24 7.3 INSURANCE 25 7.4 POST-EXCAVATION DELIVERABLES 25 7.5 COPYRIGHT 25 APPENDICES APPENDIX A REFERENCES APPENDIX B FIGURES A1 in Northumberland: Morpeth to Felton (Part A) WSI 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 SCHEME BACKGROUND 1.1.1. -

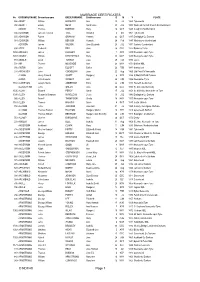

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 21/00052/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Jan. 27, 2021 Applicant: Mr Lee Hollis Agent: Mr James Cromarty 6 Ubbanford, Norham, Suite 6, 5 Kings Mount, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Ramparts Business Park, Northumberland, TD15 2LA, Berwick Upon Tweed, TD15 1TQ, Proposal: Proposed single storey rear extension Location: 6 Ubbanford, Norham, Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Northumberland, TD15 2LA, Neighbour Expiry Date: Jan. 27, 2021 Expiry Date: March 23, 2021 Case Officer: Mr Ben MacFarlane Decision Level: Ward: Norham And Islandshires Parish: Norham Application No: 20/03889/VARYCO Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Jan. 28, 2021 Applicant: Mr Terry Maughan Agent: Mr Michael Rathbone Managers House, Fram Park, 5 Church Hill, Chatton, Longframlington, Morpeth, Alnwick, NE66 5PY NE65 8DA, Proposal: Removal of condition 3 (occupation period) of application A/2004/0279 Erskine United Reformed Church And Ferguson Village Hall to allow unrestricted opening for 12 months of the year Location: Fram Park, Longframlington, Morpeth, Northumberland, NE65 8DA, Neighbour Expiry Date: Jan. -

Northumberland County Council

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 21/00438/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Feb. 26, 2021 Applicant: Mr Steven Waite Agent: Mr Garry Phillipson Weardale House, Eastwood 12 Chestnut Avenue, Redcar Villas, West Wylam, Prudhoe, East, Redcar, Cleveland, TS10 Northumberland, NE42 5NQ, 3PB Proposal: Single storey rear extension to provide kitchen and sun room Location: Weardale House, Eastwood Villas, West Wylam, Prudhoe, Northumberland, NE42 5NQ, Neighbour Expiry Date: Feb. 26, 2021 Expiry Date: April 22, 2021 Case Officer: Miss Amber Windle Decision Level: Ward: Prudhoe South Parish: Prudhoe Application No: 21/00449/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Feb. 26, 2021 Applicant: Miss Shona Ferguson Agent: Estates Office, Alnwick Castle, Alnwick, NE66 1NQ, Proposal: Proposed demolition of the existing farmhouse and replacement with a 4-bedroom dwelling; demolition and change of use of detached outbuilding and replacement with a 3-bedroom and 2-bedroom dwelling; conversion of existing L-shaped outbuilding into 2no. -

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location Map for the District Described in This Book

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location map for the district described in this book AA68 68 Duns A6105 Tweed Berwick R A6112 upon Tweed A697 Lauder A1 Northumberland Coast A698 Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Holy SCOTLAND ColdstreamColdstream Island Farne B6525 Islands A6089 Galashiels Kelso BamburghBa MelrMelroseose MillfieldMilfield Seahouses Kirk A699 B6351 Selkirk A68 YYetholmetholm B6348 A698 Wooler B6401 R Teviot JedburghJedburgh Craster A1 A68 A698 Ingram A697 R Aln A7 Hawick Northumberland NP Alnwick A6088 Alnmouth A1068 Carter Bar Alwinton t Amble ue A68 q Rothbury o C B6357 NP National R B6341 A1068 Kielder OtterburOtterburnn A1 Elsdon Kielder KielderBorder Reservoir Park ForForestWaterest Falstone Ashington Parkand FtForest Kirkwhelpington MorpethMth Park Bellingham R Wansbeck Blyth B6320 A696 Bedlington A68 A193 A1 Newcastle International Airport Ponteland A19 B6318 ChollerforChollerfordd Pennine Way A6079 B6318 NEWCASTLE Once Housesteads B6318 Gilsland Walltown BrewedBrewed Haydon A69 UPON TYNE Birdoswald NP Vindolanda Bridge A69 Wallsend Haltwhistle Corbridge Wylam Ryton yne R TTyne Brampton Hexham A695 A695 Prudhoe Gateshead A1 AA689689 A194(M) A69 A686 Washington Allendale Derwent A692 A6076 TTownown A693 A1(M) A689 ReservoirReservoir Stanley A694 Consett ChesterChester-- le-Streetle-Street Alston B6278 Lanchester Key A68 A6 Allenheads ear District boundary ■■■■■■ Course of Hadrian’s Wall and National Trail N Durham R WWear NP National Park Centre Pennine Way National Trail B6302 North Pennines Stanhope A167 A1(M) A690 National boundaryA686 Otterburn Training Area ArAreaea of 0 8 kilometres Outstanding A689 Tow Law 0 5 miles Natural Beauty Spennymoor A688 CrookCrook M6 Penrith This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright and/or database right 2007. -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland