Southern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys Volans) Den Site Selection and Genetic Relatedness of Summer Nesting Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Fagaceae Trees

CHAPTER 5 5 Fagaceae Trees Antoine Kremerl, Manuela Casasoli2,Teresa ~arreneche~,Catherine Bod6n2s1, Paul Sisco4,Thomas ~ubisiak~,Marta Scalfi6, Stefano Leonardi6,Erica ~akker~,Joukje ~uiteveld', Jeanne ~omero-Seversong, Kathiravetpillai Arumuganathanlo, Jeremy ~eror~',Caroline scotti-~aintagne", Guy Roussell, Maria Evangelista Bertocchil, Christian kxerl2,Ilga porth13, Fred ~ebard'~,Catherine clark15, John carlson16, Christophe Plomionl, Hans-Peter Koelewijn8, and Fiorella villani17 UMR Biodiversiti Genes & Communautis, INRA, 69 Route d'Arcachon, 33612 Cestas, France, e-mail: [email protected] Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita "La Sapienza", Piazza A. Moro 5,00185 Rome, Italy Unite de Recherche sur les Especes Fruitikres et la Vigne, INRA, 71 Avenue Edouard Bourlaux, 33883 Villenave d'Ornon, France The American Chestnut Foundation, One Oak Plaza, Suite 308 Asheville, NC 28801, USA Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, USDA-Forest Service, 23332 Highway 67, Saucier, MS 39574-9344, USA Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, Universitk di Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze 1lIA, 43100 Parma, Italy Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Alterra Wageningen UR, Centre for Ecosystem Studies, P.O. Box 47,6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA lo Flow Cytometry and Imaging Core Laboratory, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason, 1201 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98101, -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Oak in Focus: Quercus Rubra, Red

Oak in Focus—Red Oak Red Oak (Northern Red Oak) Similar Species: e black oak (Q. velutina) is less common than the Cris Fleming notes: “In the publication e Natural Communities of Quercus rubra L. red oak in native woodlands. Many of its leaves are similar in shape Maryland, January 2011, e Maryland Natural Heritage Program (Quercus borealis F. Michx.) (though some may be more deeply sinused, especially when lists seven ecological communities with Quercus rubra as dominant or sun-exposed) but they are dark, glossy green above and usually have co-dominant. ese community groups are acidic oak-hickory forest, aryland’s oaks have put forth an abundant acorn “scurfy” (dandru-like) pubescence below in addition to hair tufts in basic mesic forest, basic oak-hickory forest, chestnut oak forest, crop during the Maryland Native Plant Society’s the vein axils. However, the pubescence may be gone this time of year. dry-mesic calcareous forest, mixed oak-heath forest, and northern Year of the Oak and you almost need a hard hat e black oak has very dark, broken, shallowly blocky bark (without hardwood forest.” when walking in the woods this fall! Now that “ski tracks”) and exceptionally large angled buds covered with gray- we’ve had three consecutive years of bountiful white pubescence, an excellent fall and winter diagnostic. e scarlet Carole Bergmann adds: “I think that Quercus rubra is one of the most acorn production, it’s dicult to remember the oak (Q. coccinea), the pin oak (Q. palustris) and the Shumard oak (Q. common oaks in the Maryland piedmont. -

(Quercus Rubra) Populations from the Greater Sudbury Region During Reclamation

Potential genetic impacts of metal content on Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) populations from the Greater Sudbury Region during reclamation By Anh Tran Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Biology School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Ann Tran, 2013 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91872-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91872-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Spread and Role of the Invasive Alien Tree Quercus Rubra (L.) in Novel Forest Ecosystems in Central Europe

Article The Spread and Role of the Invasive Alien Tree Quercus rubra (L.) in Novel Forest Ecosystems in Central Europe Damian Chmura Institute of Nature Protection and Engineering, University of Bielsko-Biala, 2 Willowa Str, PL-43-309 Bielsko-Biała, Poland; [email protected] Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 21 May 2020; Published: 23 May 2020 Abstract: Research Highlights: The factors that control the spread and regeneration of Quercus rubra (L.) and the functional diversity of invaded forest were studied in order to indicate the significant role of disturbances in a forest and the low functional richness and evenness of sites that are occupied by red oak. Background and Objectives: Red oak is one of the most frequent invasive trees from North America in Central Europe. It is also one of the most efficient self-regenerating invasive alien species in forests. The main goal of the study is to identify the characteristics of forest communities with a contribution of Q. rubra, and to assess its role in shaping the species diversity of these novel phytocoenoses. Materials and Methods: A total of 180 phytosociological records that have a share of Q. rubra in southern Poland were collected, including 100 randomly chosen plots from which soil samples were taken. In addition, vegetation sampling was performed in 55 plots in the vicinities that were uninvaded. Results: The probability of the self-regeneration and cover of Q. rubra seedlings depends mainly on the availability of maternal trees, and the abundance of seedlings was highest in cutting areas. The vegetation with Q. rubra differed in the plant functional types and environmental factors. -

Removal of Acorns of the Alien Oak Quercus Rubra on the Ground by Scatter-Hoarding Animals in Belgian Forests Nastasia R

B A S E Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2017 21(2), 127-130 Short note Removal of acorns of the alien oak Quercus rubra on the ground by scatter-hoarding animals in Belgian forests Nastasia R. Merceron (1, 2, 3), Aurélie De Langhe (3), Héloïse Dubois (3), Olivier Garin (3), Fanny Gerarts (3), Floriane Jacquemin (3), Bruno Balligand (3), Maureen Otjacques (3), Thibaut Sabbe (3), Maud Servranckx (3), Sarah Wautelet (3), Antoine Kremer (1), Annabel J. Porté (1, 2), Arnaud Monty (3) (1) BIOGECO, INRA, University of Bordeaux. FR-33610 Cestas (France). (2) BIOGECO, INRA, University of Bordeaux. FR-33615 Pessac (France). (3) University of Liège - Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech. Biodiversity and Landscape Unit. Passage des Déportés, 2. BE-5030 Gembloux (Belgium). E-mail: [email protected] Received on June 15, 2016; accepted on February 24, 2017. Description of the subject. Quercus rubra L. is considered an invasive species in several European countries. However, little is known about its dispersal in the introduced range. Objectives. We investigated the significance of animal dispersal of Q. rubra acorns on the ground by vertebrates in its introduced range, and identified the animal species involved. Method. During two consecutive autumns, the removal of acorns from Q. rubra and from a native oak was assessed weekly in forest sites in Belgium. We used automated detection camera traps to identify the animals that removed acorns. Results. Quercus rubra acorns were removed by wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus L.), red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris L.), rats (Rattus sp.), and wild boars (Sus scrofa L.). The two former are scatter-hoarding rodents and can be considered potential dispersers. -

Reproduction and Gene Flow in the Genus Quercus L

Review article Reproduction and gene flow in the genus Quercus L A Ducousso H Michaud R Lumaret 1 INRA, BP 45, 33611 Gazinet-Cestas; 2 CEFE/CNRS, BP 5051, 34033 Montpellier Cedex, France Summary — In this paper we review the characteristics of the floral biology, life cycle and breeding system in the genus Quercus. The species of this genus are self-incompatible and have very long life spans. The focus of our review is on the effects of gene flow on the structuration of genetic varia- tion in these species. We have examined the influence of gene flow in 2 ways: 1) by measuring the physical dispersal of pollen, seed and vegetative organs; and 2) by using nuclear and cytoplasmic markers to estimate genetic parameters (Fis, Nm). These approaches have shown that nuclear (iso- zyme markers) as well as cytoplasmic (chloroplastic DNA) gene flow is usually high, so that very low interspecific differentiation occurs. However, intraspecific differentiation is higher for the cytoplasmic DNA than for the nuclear isozyme markers. floral biology / life cycle / breeding system / gene flow / oak Résumé — Système de reproduction et flux de gènes chez les espèces du genre Quercus. Les caractéristiques de la biologie florale, du cycle de vie et du système de reproduction ont été analysées pour les espèces du genre Quercus. Ces espèces sont auto-incompatibles et à très lon- gue durée de vie. Les effets des flux de gènes sur la structuration de la variabilité génétique ont aussi été étudiés de 2 manières. D’une part, grâce aux mesures de la dispersion du pollen, des graines et des organes végétatifs, et, d’autre part, en utilisant des paramètres génétiques (Fis, Nm) obtenus à partir des marqueurs nucléaires et cytoplasmiques. -

Lichens of Red Oak Quercus Rubra in the Forest Environment in the Olsztyn Lake District (NE Poland)

ACTA MYCOLOGICA Dedicated to Professor Alina Skirgiełło Vol. 41 (2): 319-328 on the occasion of her ninety-fifth birthday 2006 Lichens of red oak Quercus rubra in the forest environment in the Olsztyn Lake District (NE Poland) DARIUSZ KUBIAK Department of Mycology, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn Oczapowskiego 1A, PL-10-957 Olsztyn, [email protected] Kubiak D.: Lichens of red oak Quercus rubra in the forest environment in the Olsztyn Lake District (NE Poland). Acta Mycol. 41 (2): 319-328, 2006. A list of 63 species of lichens and 4 species of lichenicolous fungi recorded on the bark of red oak (Quercus rubra L.) in Poland is given. Literature data and the results of field studies conducted in the forest in the Olsztyn Lake District between 1999 and 2005 are used in the report. Fifty-five taxa, including lichens rare in Poland, for instance Lecanora albella, Lecidella subviridis, Ochrolechia turneri, were recorded. Key words: lichens (lichenized fungi), lichenicolous fungi, red oak (Quercus rubra), Poland INTRODUCTION Rich lichen biotas, usually comprising numerous specific species, are associat- ed with the genus Quercus L. both in Poland (Cieśliński, Tobolewski 1988; Rutkowski 1995) and in other parts of Europe (Alvarez, Carballal 2000; Zedda 2002; Engel et al. 2003). Many rare or very rare lichen species in Poland and taxa considered to be extinct have been found to colonise oak bark in Poland (Cieśliński, Tobolewski 1988; Rutkowski 1995; Rutkowski, Kukwa 2000; Fałtynowicz 1991). Its diversified texture provides niches suitable for dif- ferent lichen species while the phorophyte’s longevity influences the richness and diversity of its lichen biota. -

Quercus Rubra

Quercus rubra - Northern Red Oak or Red Oak (Fagaceae) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Quercus rubra is a large shade tree that thrives in dry that matures over 2 seasons, with a wide cap that sites, often with good brick-red autumn color, covers the upper one-fourth of the nut, on a very becoming very rounded to spreading with age. short peduncle and either single or in pairs, but Northern Red Oak is probably the most common clustered on the second-year wood and often with a landscape Oak of the Midwest. heavy mast crop (abundant fruit production) Twigs FEATURES -greenish- to reddish-brown, turning gray by the Form second year and somewhat stout -large shade tree Trunk -maturing at about 60' tall x -dark gray to black, being lightly furrowed with flat- 80' wide under urban topped subtle ridges through middle age, and conditions, but much larger becoming deeply furrowed with a light reddish in the wild interior bark in old -upright oval growth habit in age youth, becoming rounded to -branches arising spreading with age directly from the -medium growth rate trunk are relatively few, but large, Culture adding to the bold -full sun to partial sun (partial shade tolerant in texture by their youth) size, and by -performs best in full sun in moist, deep, acidic, well- exposing the large drained soils, but is very adaptable to poor soils, dry trunk more than soils, and soils of various pH most Oaks -propagated by seeds -no serious diseases or pests USAGE -commonly available -

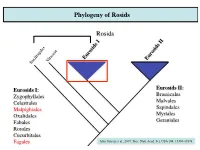

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

(LONICERA MAACKII) COMPARED to OTHER WOODY SPECIES By

ABSTRACT BEAVER (CASTOR CANADENSIS) ELECTIVITY FOR AMUR HONEYSUCKLE (LONICERA MAACKII) COMPARED TO OTHER WOODY SPECIES by Janet L. Deardorff The North American beaver is a keystone riparian obligate which creates and maintains riparian areas by building dams. In much of the eastern U.S., invasive shrubs are common in riparian zones, but we do not know if beavers promote or inhibit these invasions. I investigated whether beavers use the invasive shrub, Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), preferentially compared to other woody species and the causes of differences in L. maackii electivity among sites. At eight sites, I identified woody stems on transects, recording stem diameter, distance to the water’s edge, and whether the stem was cut by beaver. To determine predictors of cutting by beaver, I conducted binomial generalized regressions, using distance from the water’s edge, diameter, and plant genus as fixed factors and site as a random factor. To quantify beaver preference, I calculated an electivity index (Ei) for each genus at each site. Lonicera maackii was only preferred at two of the eight sites though it comprised 41% of the total cut stems. Stems that were closer to the water’s edge and with a smaller diameter had a higher probability of being cut. Among sites, L. maackii electivity was negatively associated with the density of stems of preferred genera. BEAVER (CASTOR CANADENSIS) ELECTIVITY FOR AMUR HONEYSUCKLE (LONICERA MAACKII) COMPARED TO OTHER WOODY SPECIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science by Janet L. -

An Evaluation of Northern Red Oak (Quercus Rubra) at Seney National Wildlife Refuge (2005)

An Evaluation of Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) at Seney National Wildlife Refuge (2005) K.A. Henslee Applied Conservation Biology Intern Seney National Wildlife Refuge, Seney, MI 49883 Introduction Northern red oak (Quercus rubra) is a widespread and common deciduous tree species found throughout eastern North America (Figure 1). It grows best on well drained upland soils with a north or east aspect at elevations between 0-1,800 m (0-5,900 ft) and can reach dimensions of 20-30 m (65-98 ft) in height and 61-91 cm (24-36 in) in diameter (USDA 2005). Northern red oak can live up to 500 years. Northern red oak is identifiable by several distinct characteristics. The tree derives its common name from the red hue the foliage turns in the fall and the red coloration of the petioles and heartwood. The leaves are alternate, simple, 10-25 cm (5-8 in) in length, yellow-green above and have 7-11 bristle tipped lobes. The bark can be various shades of dark brown to black and is smooth on young trees, forming “ski-track” like fissures with flat ridges as the tree matures. Acorns are 2-3 cm (1 in) in length, a third of which is covered by a flat cap, lined with fine silky hairs (USDA 2005). Northern red oak can produce acorns as early as 25 years of age, with larger and more abundant crops occurring after age 50. Masting intervals occur every two-five years and the number of acorns produced varies between individual trees and subsequent years based on weather conditions (USDA 2005).