Leadership with Integrity C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meet 22 of the Region's Top Brand Builders & Advisers at Malaysia's

14th 2017 The 14th Superlative Annual Brand Marketing Conference 15 & 16 May, 2017 www.brandfest.com.my Meet 22 of the Region’s Top Brand Builders & Advisers at Malaysia’s Most Informative Annual Brand Marketing Conference 100% HRDF Claimable! Special Group Rate: RM1320.00 nett per pax (3 delegates and more) www.brandfest.com.my The 14th Brandfest 2017: Malaysia’s Not-to-be-Missed Annual Conference on Contemporary Brand Marketing 15 May 2017, Monday (DAY 1) 7.45 Registration and Morning Coffee this key transformation in brand marketing in Southeast Asia and in particular, Malaysia. 9.00 Welcome Remarks by the Chair: • How brands can reach to relevant and targeted audiences Andreas Vogiatzakis, CEO, Havas Media Group Malaysia • How to maximize your Marketing ROI online • What are some ways to become engaging and more relevant to KEYNOTE ADDRESS your customers online REBRANDING BEST PRACTICES & FAILURES • Valuable lessons for Brand Builders. 9.15 The Experiences of Brands that Have Evolved & Andrew is currently the Chief Marketing Officer of Lazada Malaysia, Malaysia’s Stepped Up to the Times with Strategic Rebranding #1 e-commerce marketplace - where he leads their digital marketing, brand building and conversion optimization efforts. Prior to Lazada, Andrew consulted for the Boston Consulting Group, the World Bank and Endeavor Zayn Khan, Chief Executive Officer (SEA) Global - helping companies in various stages of growth to scale up their Dragon Rouge, Singapore operations and enter new markets. Andrew is obsessed about making data- Brand Custodians will in time pass by a red flag that clearly states “Rebrand!” driven decisions, nailing product-market fit and building border-less, high History has shown that some act fast; and others after customers have performance teams. -

Kuwait COVID Death Toll Tops 1,000 After 5 More Fatalities

RAJAB 3, 1442 AH MONDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2021 16 Pages Max 28º Min 10º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18361 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Ministry sets prices at fish Blaze destroys hundreds of fuel Egypt unearths ‘world’s oldest’ West Brom draw damages 4 market after auctions halted 5 tankers on Afghan-Iran border 12 mass-production brewery 16 Manchester United title bid Kuwait COVID death toll tops 1,000 after 5 more fatalities Govt to attend session on coronavirus • Calls to scrap institutional quarantine By B Izzak Marzouq Al-Ghanem said he was informed by mier. He said that he will not attend the ses- HH the Prime Minister Sheikh Sabah Al- sion unless the new Cabinet is formed. A simi- KUWAIT: The health ministry yesterday Khaled Al-Sabah, who is still forming the new lar position was expressed by MPs Saud Al- registered 798 COVID-19 cases over a 24- Cabinet, that the outgoing government will Mutairi, Hamdan Al-Azemi, Fares Al-Otaibi hour period, taking the total number of infec- attend the special session called by MPs. and Mohammad Al-Mutair. tions to 177,701, while five fatalities were MP Osama Al-Munawer and a group of Two lawmakers also called on the govern- recorded, raising the death toll to 1,003. lawmakers submitted a motion last week to ment to review its decision on forcing arrivals Active cases amounted to 10,679 with 133 hold a special session to debate the new to be placed in institutional quarantine for patients in intensive care units, Spokesman Dr strain of the coronavirus and recent gov- seven days at their cost. -

University Court Videoconference Monday, 26 April 2021 AGENDA 1

University Court Videoconference Monday, 26 April 2021 AGENDA 1 Minute A1, A2 To approve the minute of the meeting and note of the seminar held on 22 February 2021 2 Matters Arising & Review of Action Log A3 To raise any matters arising and review the Action Log 3 Principal’s Report B To note a report from Peter Mathieson, Principal SUBSTANTIVE ITEMS 4 Adaptation & Renewal Team Report C To note a report from Barry Neilson, Director of Strategic Change 5 Support for Students at Risk of Self-Harm D To note a briefing paper from Gavin Douglas, Deputy Secretary Student Experience 6 Students’ Association and Sports Union Reports To note the reports presented by Ellen MacRae, EUSA President • Students’ Association Report E1 • Sports Union Report E2 7 Director of Finance’s Report F To note a report by Lee Hamill, Director of Finance 8 Equality Reporting To approve the reports presented by Sarah Cunningham-Burley, University Lead for Equality, Diversity & Inclusion: • EDMARC Staff and Student Reports 2020 G1 • Equality Outcomes 2021-25, and Equality Mainstreaming and G2 Outcomes Progress Report 2017-21 9 Gujarat Biotechnology University – Final Agreement H To approve a paper presented by David Gray, Head of School of Biological Sciences ITEMS FOR NOTING OR FORMAL APPROVAL 10 Estates Small Works Programme I To approve 11 Governance Apprenticeship Programme J To approve 12 General Council Prince Philip Fund K To approve 13 Committee Reports • Exception Committee L1 • Policy & Resources Committee L2 • Audit & Risk Committee L3 • Knowledge Strategy -

Prologue This Report Is Submitted Pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264)

Prologue This report is submitted pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264). Section 4 of this law provides, in part, that: ―The President shall from time to time as occasion may require, but not less than once each year, make reports to the Congress of the activities of the United Nations and of the participation of the United States therein.‖ In July 2003, the President delegated to the Secretary of State the authority to transmit this report to Congress. The United States Participation in the United Nations report is a survey of the activities of the U.S. Government in the United Nations and its agencies, as well as the activities of the United Nations and those agencies themselves. More specifically, this report seeks to assess UN achievements during 2007, the effectiveness of U.S. participation in the United Nations, and whether U.S. goals were advanced or thwarted. The United States is committed to the founding ideals of the United Nations. Addressing the UN General Assembly in 2007, President Bush said: ―With the commitment and courage of this chamber, we can build a world where people are free to speak, assemble, and worship as they wish; a world where children in every nation grow up healthy, get a decent education, and look to the future with hope; a world where opportunity crosses every border. America will lead toward this vision where all are created equal, and free to pursue their dreams. This is the founding conviction of my country. It is the promise that established this body. -

India Legal Forum Presents Webinar Series on "Intellectual Property Rights: an Overview and Its Implications in the Pharmaceutical Industry.”

ALL INDIA LEGAL FORUM ALL INDIA LEGAL FORUM PRESENTS WEBINAR SERIES ON "INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS: AN OVERVIEW AND ITS IMPLICATIONS IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY.” Event collaborators ABOUT THE ORGANISER: All India Legal Forum, the brainchild of several legal luminaries and eminent personalities across the country and the globe, is a dream online platform which aims at proliferating legal Knowledge and providing an ingenious understanding and cognizance of various fields of law, simultaneously aiming to generate diverse social, political, legal and constitutional discourse on law-related topics, making sure that legal knowledge penetrates to every nook and corner of the ever-growing legal fraternity. All India Legal Forum also houses a blog that addresses contemporary issues in any field of law. We at All India Legal Forum don’t just publish blogs, we also guide the authors when their research paper is not up to the mark. HONORARY BOARD: All India Legal Forum is pleased to have support of diverse group of eminent personalities, comprising: Justice Arjan Kumar Sikri, Justice Mukundakam Sharma, Justice Bellur Srikrishna, Justice S.L. Bhayana, Justice Amarnath Jindal, Dr. Vinod Surana, CEO and Partner, Surana and Surana International Attorneys, Mr. Ajit Prakash Shah, Former Chairman, 20th Law Commission of India, Mr. Rishabh Gupta, Partner, Shardul Amarchand and Mangal Das, Mr. M S Bharath, Senior Partner, Anand and Anand Associates, Mr. Safir Anand, Senior Partner, Anand and Anand Associates, Mr. JLN Murthy and many more. ABOUT THE WEBINAR SERIES: All India Legal Forum after conducting a successful Webinar Tri-Series on the Cyber Laws now has come up with another First National Mega Webinar Series on Intellectual Property Rights. -

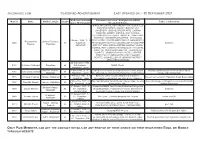

Jogsanjog.Com Classified Adveritsement Last Updated on :- 30 September 2021

JOGSANJOG.COM CLASSIFIED ADVERITSEMENT LAST UPDATED ON :- 30 SEPTEMBER 2021 DOB, time and birth Education Profession / Salary/Income PM/PA Matri id Name Nanihal , Origin Height Father 's information place 'M' if manglik /Occupation Details M.PHIL IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY (RCI LICENCED) MASTERS IN PSYCHOLOGY (BANASTHALI UNIVERSITY ) BACHELORS OF ARTS ( SOPHIA COLLEGE, AJMER) , CONSULTANT CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AT GOYAL HOSPITAL, MANIDHARI HOSPITAL, VASUNDHRA HOSPITAL, VRINDAVAN 5 October 1994 , 3 : 32 PSYCHIATRIC CENTRE DIRECTOR AT AMELIORATE ( Priyadarshini Udawat (Rathore) , 8240 63 , Rajasthan , PSYCHOLOGY CENTRE) COUNSELLOR AT JODHPUR Business Rajawat Rajasthan JODHPUR DISTRICT ARMY ORGANISATION MONTHLY 90,000, CONSULTANT CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AT GOYAL HOSPITAL, MANIDHARI HOSPITAL, VASUNDHRA HOSPITAL, VRINDAVAN PSYCHIATRIC CENTRE DIRECTOR AT AMELIORATE ( PSYCHOLOGY CENTRE) COUNSELLOR AT JODHPUR DISTRICT ARMY ORGANISATION 20 September 1990 , 8123 Dr Kusum Nathawat Rajasthan 66 Not Available , MBBS, Doctor Rajasthan , Jaipur Rathore- mertiya , 7 May 1996 , 2 : 45 , DVM (doctor of veterinary medicine) from CVAS, bikane, Assistant administrative officer at govt.medical 8173 Yashmita Shekhawat 64 Rajasthan Rajasthan , Jaipur Inte, ship student, Pursuing internship from CVAS, bikaner college and hospital,sikar 1 February 1991 , 5 : 0 Bachelor of Homeopathy Medicine and Surgery, 7515 Dr Neha Chauhan Tanwar , Rajasthan 64 Government servant in Rajasthan Khadi Board Jaipur , Rajasthan , Jaipur Successfully running Her own clinic at our residence -

Witchcraft, Violence and Everyday Life: an Ethnographic Study of Kinshasa

WITCHCRAFT, VIOLENCE AND EVERYDAY LIFE: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF KINSHASA A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY SILVIA DE FAVERI COLLEGE OF BUSINESS, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, MEDIA AND COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION OF ANTHROPOLOGY BRUNEL UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2014 Abstract The inhabitants of Kinshasa, who call themselves Kinois, deal with insecurity and violence on a daily basis. Cheating and thefts are commonplace, and pillaging by street gangs and robberies by armed thieves are everyday occurrences. The state infrastructure is so poorly regulated that deaths by accident or medical negligence are also common. This, and much more, contributes to a challenging social milieu within which the Kinois’ best hope is simply to ‘make do’. This thesis, based on extensive fieldwork in Kinshasa, analyses different forms of violence which affect the Kinois on a daily basis. I argue that the Kinois’ concept of violence, mobulu, differs from Western definitions, which define violence as an intrinsically negative and destructive force. Mobulu is for the Kinois a potentially constructive phenomenon, which allows them to build relationships, coping strategies and new social phenomena. Violence is perceived as a transformative force, through which people build meaningful lives in the face of the hardship of everyday life. Broadly speaking, this thesis contributes to the Anthropology of violence which has too often focused on how violence is imposed upon a population, often from a structural level of a state and its institutions. Such an approach fails to account for the nuances of alternate perspectives of what ‘violence’ is, as evidenced in this thesis through the prism of the Kinois term mobulu. -

Against PDF for Women Scheme for the Year 2012-13 & 2013-14

A list of shortlisted candidates (1101) against PDF for women scheme for the year 2012-13 & 2013-14 is being uploaded on the UGC website. Shortlisted candidates are requested to keep themselves ready to reach UGC office as per schedule of dates fixed (Subject-wise) during the period from 18.03.2014 to 28.03.2014. All candidates may also carry their CVC/Biodata a copy of their proposal alongwith record of their publications/books. Presentation can also be done , if required & necessary. Schedule will follow in coming one or two days. List of Shortlisted Candidates under Post Doctroal Fellowship for Women (2012-13 & 2013-14) S.No. Candidate ID Name DOB Place of Research Subject 1 PDFWM-2013-14-OB-TAM- D.MURUGANANTHI 5/23/1982 Tamil Nadu Agricultural university Agriculture 21816 2 PDFWM-2012-13-OB-TAM- ANBUKKARASI K 5/25/1981 TamilNadu Agricultural University Agriculture 20045 3 PDFWM-2013-14-SC-UTT- VANDANA KUMARI 09-12-1981 Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar University Agriculture 17466 Agra 4 PDFWM-2012-13-GE-GUJ- POONAM RAJWANSHI 12/14/1968 University Agriculture 18265 5 PDFWM-2013-14-GE-WES- ADITI CHATTOPADHYAY 2/25/1984 Bidhan Chandra Krishi Agriculture 19117 Viswavidyalaya 6 PDFWM-2013-14-GE-UTT- ARPITA SHARMA 3/27/1985 G.B.P.U.A&T. PANTNAGAR, Agriculture 13707 UTTARAKHAND-263145 7 PDFWM-2013-14-GE-ASS- PUSPA BHUYAN 3/1/1973 Gauhati University Agriculture 21628 8 PDFWM-2013-14-GE-JAM- AMARDEEP KOUR 4/2/1980 Punjab Agricultural University, Agriculture 17049 Ludhiana 9 PDFWM-2012-13-GE-WES- KANTA BOKARIA 2/8/1964 INDIAN STATISTICAL Agriculture 12396 -

Embodied Histories, Danced Religions, Performed Politics: Kongo Cultural Performance and the Production of History and Authority

Embodied Histories, Danced Religions, Performed Politics: Kongo Cultural Performance and the Production of History and Authority by Yolanda Denise Covington A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Elisha P. Renne, Chair Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew Associate Professor Mbala D. Nkanga Assistant Professor Julius S. Scott III © Yolanda Denise Covington 2008 To my grandmother NeNe ii Acknowledgements When I look back on my experiences, it seems as if I was guided by some unseen hand. From my acceptance into the A Better Chance Program for high school, to my career switch from medicine to anthropology/Africana Studies at Brown University, to my trips to Panama, and finally to Congo while at the University of Michigan, I often felt as if my path was being determined by someone else and I was just traveling along it. Along the way, however, I met many wonderful people who have played crucial roles in my journey, and I have to thank them for getting me here. This dissertation is really a collaborative project, for I could not have completed it without the guidance and assistance of so many people. The first person I have to thank is my grandmother, who has inspired and encouraged from my days at C.E.S. 110X in the Bronx. She has always been supportive and continues to push me to reach my highest potential. I could not have reached this point without a great support system and wonderful dissertation committee. -

Dr Pathy Book.Pdf

dinanath Published by Third Eye Communications A unit of Ketaki Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. N-4/252, IRC Village, Bhubaneswar Odisha. India 751015 E [email protected] With Support from IPCA ILa Panda Centre for Arts Bhubaneswar Dr. Dinanath Pathy left this material and world doing what he loved most; working for the cause of art and for Print-Tech Offset Pvt. Ltd. what he believed to be right. He left behind a vast expanse of memories and Bhubaneswar experiences which can never be filled in. In this publication we have earnestly tried Concept, Layout and Design to create the memories of the legendary Jyotiranjan Swain painter, writer and art philosopher Satyabhusan Hota through a collection of pictures. There are many more images and memories Photographs which could not be included due to limitations of time and immediate Ramahari Jena, A. Prathap, PC Dhir, availability of materials. We are looking Jyotiranjan Swain, Subrat Das, Sangram forward to touching other aspects of his Jena, Soubhagya Pathy, Abtin Javid, life in our future publications. IPCA, Angarag and Sutra Foundation Dr. Dinanath Pathy 1942-2016 Painter, Writer and Art Historian A distinguished practicing painter and pioneer of the Modern and Contemporary Art Movement of Odisha, Dr. Dinanath Pathy was brought up in a family of artists and poets in the traditional town of Digapahandi, Ganjam in Odisha. In education and training, he combined both traditional Guru-Sisya Parampara as well as the modern university system. He studied at Khallikote, Bhubaneswar, Santiniketan and Zurich. He wrote two dissertations: History of Orissan Painting, and Art and Regional Traditions. -

Births, Deaths, Labour and Militarized Border-Crossing Among Sex Workers in an Area of Armed Conflict in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo

Chercher La Vie : Births, Deaths, Labour and Militarized Border-Crossing among Sex Workers in an Area of Armed Conflict in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo by Anna-Louise Crago A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology Department University of Toronto © Copyright by Anna-Louise Crago 2020 Chercher La Vie : Births, Deaths, Labour and Militarized Border- Crossing among Sex Workers in an Area of Armed Conflict in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo Anna-Louise Crago Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology University of Toronto 2020 Abstract This dissertation is a study of sociality and power in armed conflict. It is based on ethnographic research with two groups of women who sell sex in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, self-identified “ bambaragas ”. These women travel back and forth across militarized lines in areas of armed conflict to perform sex work and other complementary labour and to trade with a variety of different state and non-state armed groups. This study argues that any attempt to understand sociality and power in war must grapple centrally with non-violent death. The combined effects of armed conflict and privatization contributed to mass infant, child and maternal death. Bambaragas and their children bore a distinct and disproportionate death burden. Hospitals sat at the intersection of governance of health as a private commodity rather than a public entitlement, by both the state and non-state armed groups. This resulted in policies within hospitals of refusing emergency care, abusing and punishing women suspected of abortion, imposing debt and extracting payment, and forcibly detaining women who couldn’t pay for their or their children’s care. -

Diplomatic and Consular List

DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR LIST September 2019 DEPARTMENT OF PROTOCOL MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS BANGKOK It is requested that amendment be reported without delay to the Protocol Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This List is up-to-date at the time of printing, but there are inevitably frequent changes and amendments. CONTENTS Order of Precedence of Heads of Missions ............................................................................... 1 - 7 Diplomatic Missions ............................................................................................................. 8 - 232 Consular Representatives .................................................................................................. 233 - 250 Consular Representatives (Honorary) ............................................................................... 251 - 364 United Nations Organizations ........................................................................................... 365 - 388 International Organizations ............................................................................................... 389 - 403 Public Holidays for 2019 .................................................................................................. 404 - 405 MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS BANGKOK Order of Precedence of Heads of Missions ORDER OF PRECEDENCE Ambassadors Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary * Belize H.E. Mr. David Allan Kirkwood Gibson…………………………………………... 12.02.2004 Order of Malta H.E. Mr. Michael Douglas Mann…………………………………………………... 29.09.2004 * Dominican