RTV Trend Report 2020. Right-Wing Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An American Perspective on Amok Attacks

Research Note no 30 December 2017 Centre de Recherche de l’École des Officiers de la Gendarmerie Nationale An American perspective on Amok attacks By Second-lieutenant Alexandre Rodde (French National gendarmery reserve) On March 16th 2017, at 12:50, Killian B. entered the Alexis de Tocqueville High School in Grasse (French Riviera), carrying several weapons. The shooting spree that ensued, lasted ten minutes, and left five victims injured, before the French National Police was able to arrest the attacker1. In France, this type of attack is a new challenge for law-enforcement forces, especially for intervention squads. These weaponized attacks without any political motive - known in France as “amok attacks”2 - are often mistaken for terrorist attacks, notwithstanding their differences. So, let us ask ourselves : what differenciates such an attack from a terrorist one ? Defined as “an episode of sudden mass assault”3 the Malaysian word “amok” was popularized in a 1922 novel by Stefan Zweig4. Modern amok attacks can be described as a sudden assault, in a densely populated area or premise, by a lone attacker5, using one or several firearms6. The United States are used to these attacks, which have been carefully described and studied by local academics and practitioners. Lessons learned from the USA deserve to be known by the French security forces. Amok attackers, unlike lone- wolf terrorists, do not act according to political or religious agendas, but due to a personal motive7. The differences between both types of attack include their respective targets, methods and purpose. It is therefore important first to assess the threat in France (I), then to study the operational challenge it raises for both the French law-enforcement agencies and the French people (II). -

Islamophobia and Religious Intolerance: Threats to Global Peace and Harmonious Co-Existence

Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies (QIJIS) Volume 8, Number 2, 2020 DOI : 10.21043/qijis.v8i2.6811 ISLAMOPHOBIA AND RELIGIOUS INTOLERANCE: THREATS TO GLOBAL PEACE AND HARMONIOUS CO-EXISTENCE Kazeem Oluwaseun DAUDA National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN), Jabi-Abuja, Nigeria Consultant, FARKAZ Technologies & Education Consulting Int’l, Ijebu-Ode [email protected] Abstract Recent events show that there are heightened fear, hostilities, prejudices and discriminations associated with religion in virtually every part of the world. It becomes almost impossible to watch news daily without scenes of religious intolerance and violence with dire consequences for societal peace. This paper examines the trends, causes and implications of Islamophobia and religious intolerance for global peace and harmonious co-existence. It relies on content analysis of secondary sources of data. It notes that fear and hatred associated with Islām and persecution of Muslims is the fallout of religious intolerance as reflected in most melee and growingverbal attacks, trends anti-Muslim of far-right hatred,or right-wing racism, extremists xenophobia,. It revealsanti-Sharī’ah that Islamophobia policies, high-profile and religious terrorist intolerance attacks, have and loss of lives, wanton destruction of property, violation led to proliferation of attacks on Muslims, incessant of Muslims’ fundamental rights and freedom, rising fear of insecurity, and distrust between Muslims and QIJIS, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2020 257 Kazeem Oluwaseun DAUDA The paper concludes that escalating Islamophobic attacks and religious intolerance globally hadnon-Muslims. constituted a serious threat to world peace and harmonious co-existence. Relevant resolutions in curbing rising trends of Islamophobia and religious intolerance are suggested. -

Is the United States an Outlier in Public Mass Shootings? a Comment on Adam Lankford

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: https://journaltalk.net/articles/5980/ ECON JOURNAL WATCH 16(1) March 2019: 37–68 Is the United States an Outlier in Public Mass Shootings? A Comment on Adam Lankford John R. Lott, Jr.1 and Carlisle E. Moody2 LINK TO ABSTRACT In 2016, Adam Lankford published an article in Violence and Victims titled “Public Mass Shooters and Firearms: A Cross-National Study of 171 Countries.” In the article he concludes: “Despite having less than 5% of the global population (World Factbook, 2014), it [the United States] had 31% of global public mass shooters” (Lankford 2016, 195). Lankford claims to show that over the 47 years from 1966 to 2012, both in the United States and around the world there were 292 cases of “public mass shooters” of which 90, or 31 percent, were American. Lankford attributes America’s outsized percentage of international public mass shooters to widespread gun ownership. Besides doing so in the article, he has done so in public discourse (e.g., Lankford 2017). Lankford’s findings struck a chord with President Obama: “I say this every time we’ve got one of these mass shootings: This just doesn’t happen in other countries.” —President Obama, news conference at COP21 climate conference in Paris, Dec. 1, 2015 (link) 1. Crime Prevention Research Center, Alexandria, VA 22302. 2. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23187; Crime Prevention Research Center, Alexan- dria, VA 22302. We would like to thank Lloyd Cohen, James Alan Fox, Tim Groseclose, Robert Hansen, Gary Kleck, Tom Kovandzic, Joyce Lee Malcolm, Craig Newmark, Scott Masten, Paul Rubin, and Mike Weisser for providing helpful comments. -

A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States

ICCT Policy Brief October 2019 DOI: 10.19165/2019.2.06 ISSN: 2468-0486 A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States Author: Sam Jackson Over the past two years, and in the wake of deadly attacks in Charlottesville and Pittsburgh, attention paid to right-wing extremism in the United States has grown. Most of this attention focuses on racist extremism, overlooking other forms of right-wing extremism. This article presents a schema of three main forms of right-wing extremism in the United States in order to more clearly understand the landscape: racist extremism, nativist extremism, and anti-government extremism. Additionally, it describes the two primary subcategories of anti-government extremism: the patriot/militia movement and sovereign citizens. Finally, it discusses whether this schema can be applied to right-wing extremism in non-U.S. contexts. Key words: right-wing extremism, racism, nativism, anti-government A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States Introduction Since the public emergence of the so-called “alt-right” in the United States—seen most dramatically at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017—there has been increasing attention paid to right-wing extremism (RWE) in the United States, particularly racist right-wing extremism.1 Violent incidents like Robert Bowers’ attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in October 2018; the mosque shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019; and the mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas in August -

Article: Why Dylann Roof Is a Terrorist Under Federal Law, and Why It Matters

ARTICLE: WHY DYLANN ROOF IS A TERRORIST UNDER FEDERAL LAW, AND WHY IT MATTERS Winter, 2017 Reporter 54 Harv. J. on Legis. 259 * Length: 19820 words Author: Jesse J. Norris 1 * Highlight After white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine African-Americans at a Charleston, South Carolina church, authorities declined to refer to the attack as terrorism. Many objected to the government's apparent double standard in its treatment of Muslim versus non-Muslim extremists and called on the government to treat the massacre as terrorism. Yet the government has neither charged Roof with a terrorist offense nor labeled the attack as terrorism. This Article argues that although the government was unable to charge Roof with terrorist crimes because of the lack of applicable statutes, the Charleston massacre still qualifies as terrorism under federal law. Roof's attack clearly falls under the government's prevailing definition of domestic terrorism. It also qualifies for a terrorism sentencing enhancement, or at least an upward departure from the sentencing guidelines, as well as for the terrorism aggravating factor considered by juries in deciding whether to impose the death penalty. Labeling Roof's attack as terrorism could have several important implications, not only in terms of sentencing, but also in terms of government accountability, the prudent allocation of counterterrorism resources, balanced media coverage, and public cooperation in preventing terrorism. For these reasons, this Article contends that the government should treat the Charleston massacre, and similar ideologically motivated killings, as terrorism. This Article also makes two policy suggestions meant to facilitate a more consistent use of the term terrorism. -

Prayer Shaming"

God, Life, and Everything "Prayer Shaming" So many topics and so little time. Just in the last week or so, there's been a letter to the editor complaining about my column criticizing those who blame or seem to blame all Islam for terror (I've written a response, but it'll have to wait a few weeks); Jerry Falwell, Jr.'s call for students at Liberty University to carry weapons as defense against Muslims; the cartoon of Santa being arrested for Identity theft, and of course, Advent. With the rash of religion-based topics in the news these days, I really need a daily column to get it all in! But I'll focus this week one that is pretty basic. Prayer. In the wake of the past couple of mass shootings (by "mass shooting" I understand a situation in which four or more people are shot by one party), there has been a frustrated criticism of politicians and Facebook posts that say, "Our thoughts and prayers are with [name of victim community]." The New York Daily News ran a loud front page headline last Thursday that read: "God Isn't Fixing This." What's behind this "Prayer Shaming" as the criticism has been dubbed? Do people no longer believe in prayer? Should we no longer pray for victims of violence? Actually, I believe the criticism is more nuanced. I believe it has nothing to do with whether or not critics believe in the efficacy of prayer. In fact, I know several folks who pray regularly yet have taken part in this very public critique on it. -

The Sixteen Deadliest Mass Shootings in Europe, 1987-2015

The Deadliest Non-Terrorist Mass Shootings in Europe, 1987-2015* Date Place Shot dead Legal status of Firearms and Perpetrators 24 Feb 2015 Uherský Brod, Czech Republic 8 + 1 Legal pistols, licensed gun owner 9 Apr 2013 Velika Ivanča, Serbia 13 + 1 Registered pistol, licensed gun owner 22 Jul 2011 Oslo, Norway 69 Legal firearms, licensed gun club member 30 Aug 2010 Bratislava, Slovakia 7 + 1 Legal assault rifle, licensed gun club member 2 Jun 2010 Cumbria, England 12 + 1 Legal rifle & shotgun, licensed gun owner 11 Mar 2009 Stuttgart, Germany 15 + 1 Legal handgun, father a pistol club member 23 Sep 2008 Kauhajoki, Finland 10 + 1 Legal handgun, licensed pistol club member 7 Nov 2007 Tuusula, Finland 8 + 1 Legal handgun, licensed pistol club member 15 Oct 2002 Chieri, Italy 7 + 1 Legal guns, licensed gun collector 26 Apr 2002 Erfurt, Germany 16 + 1 Legal guns, licensed pistol club member 27 Mar 2002 Nanterre, France 8 Legal guns, licensed pistol club member 27 Sep 2001 Zug, Switzerland 14 + 1 Legal guns, licensed pistol owner 9 Nov 1999 Bielefeld, Germany 7 + 1 Unconfirmed – pistol, most likely unlawfully held 13 Mar 1996 Dunblane Scotland 17 + 1 Legal guns, licensed pistol club member 19 Aug 1987 Hungerford, England 16 + 1 Legal guns, licensed pistol club member Total victims + perpetrators shot: 227 + 13 * As no known study reveals the legal status of firearms used in European gun homicide to a lower threshold, ‘Mass Shooting’ is defined here as a multiple homicide committed by one or more perpetrators in which seven or more victims died by gunshot in proximate events in a civilian setting not involving terrorism and where one or more firearms were the primary cause of death, not counting any perpetrators killed by their own hand or otherwise. -

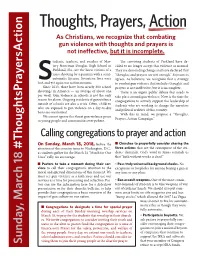

Thoughts, Prayers, Action As Christians, We Recognize That Combating Gun Violence with Thoughts and Prayers Is Not Ineffective, but It Is Incomplete

Thoughts, Prayers, Action As Christians, we recognize that combating gun violence with thoughts and prayers is not ineffective, but it is incomplete. tudents, teachers, and coaches of Mar- The surviving students of Parkland have de- jory Stoneman Douglas High School in cided to no longer accept this violence as normal. Parkland, Fla., are the latest victims of a They are demanding change and have declared that mass shooting by a gunman with a semi- “thoughts and prayers are not enough.” Sojourners automatic firearm. Seventeen lives were agrees. As believers, we recognize that a strategy Slost, and yet again our nation mourns. to combat gun violence that includes thoughts and Since 2013, there have been nearly 300 school prayers is not ineffective, but it is incomplete. shootings in America — an average of about one There is an urgent public debate that needs to per week. Gun violence in schools is not the only take place around gun violence. Now is the time for reason for alarm. Ongoing incidents of gun violence congregations to actively support the leadership of outside of schools are also a crisis. Often, children students who are working to change the narrative who are exposed to gun violence on a day-to-day and political realities of this country. basis are overlooked. With this in mind, we propose a “Thoughts, We cannot ignore the threat gun violence poses Prayers, Action Campaign.” to young people and communities everywhere. Calling congregations to prayer and action On Sunday, March 18, 2018, before the n Churches to prayerfully consider sharing the attention of the country turns to Washington, D.C., three actions that are the centerpiece of the stu- #ThoughtsPrayersAction as students gather for the March 24 “March for Our dents’ demands. -

Germany Hanau: Far-Right Terror Attack

Hanau: Far-Right Terror Attack GERMANY HANAU: FAR-RIGHT TERROR ATTACK solaceglobal.com Page 0 Hanau: Far-Right Terror Attack Hanau: Far-Right Terror Attack Executive Summary At approximately 22:00 local time on Wednesday, 19 February, a lone gunman launched two deadly attacks targeting Shisha bars in Hanau, Hesse, a commuter town roughly 25 kilometres east of Frankfurt, killing at least nine people and seriously injuring several others. The shootings triggered a large-scale police response operation and a seven-hour manhunt while officers searched for what they initially believed could have been multiple assailants. A single suspect was later identified, found dead at his home, along with the body of a second person. At the time of writing, the motive for the attacks remains unclear. The shooter is, however, understood to have allegedly left material expressing far-right extremist views, as well as a suicide letter and video claiming responsibility. Additionally, the attack targeted two shisha bars predominantly frequented by Kurdish or Turkish clients, supporting the hypothesis of a targeted attack. As of Thursday, 20 February, federal prosecutors have taken charge of the investigation amid the reports of a possible terrorist motive. Shisha Bars Targeted in Two Shootings According to local media reports, the attack commenced at around 22:00 local time when eight or nine gunshots were fired at the shisha bar, Midnight, on Heumarkt in the centre of the town. The perpetrator is then believed to have then fled the scene in a vehicle towards Kurt-Schumacher-Platz, where, shortly after the initial attack, he opened fire at a second shisha bar, the Arena Bar & Café, in the western Kesselstadt district. -

John Henry Smith: for Connecticut Public Radio, I'm John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith: For Connecticut public radio, I'm John Henry Smith. Once again, politicians are offering thoughts and prayers to victims of a mass shooting and their loved ones. This latest mass shooting in Boulder, Colorado has claimed 10 lives. Our next guest indicates any attempt to say this is a mental illness problem is wrong-headed. She is Kathy Flaherty, Executive Director of the Connecticut Legal Rights Project. Her organization provides legal services to low income persons with psychiatric disability, statewide. Kathy, what effect has the tendency to blame mass shootings on mental illness done to folks here in Connecticut who are indeed clinically mentally ill? Kathy Flaherty: Because, I am a person who lives in recovery from a mental health diagnosis. I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder back when I was in law school. Whenever a new mass shooting event occurs, you're basically waiting for the other shoe to drop. Sooner or later, the blame gets placed on mental illness, rather than looking at bigger systemic issues. And, I understand in one way why that happens because most of us, we really just can't comprehend what it would take for a person to get to the point where they would do something like this. My perspective is, though, is it really is very rarely related to a diagnosed mental health condition, and often a result of many other things, including a perspective of white male supremacy, racism, misogyny, a whole lot of very toxic stuff mixed together, that results in rage and people taking that rage out with a weapon. -

Mass Shootings and Offenders' Motives

MASS SHOOTINGS AND OFFENDERS’ MOTIVES: A COMPARISON OF THE UNITED STATES AND FOREIGN NATIONS Vanessa Terrades* I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 399 II. MASS SHOOTINGS IN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES .......................... 400 A. The United States .......................................................................... 400 B. European Countries ...................................................................... 409 C. Australia ........................................................................................ 411 D. Latin America ............................................................................... 413 III. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS ....................................................... 414 A. United States and Mexico ............................................................. 414 B. United States and Australia .......................................................... 415 C. United States and Europe ............................................................. 417 IV. RESOLUTIONS TO PREVENT OR REDUCE THE RISK OF MASS SHOOTINGS ...................................................................................... 417 A. Improve Mental Illness Treatment ................................................ 417 B. Gun Control .................................................................................. 419 C. Target Hardening .......................................................................... 421 D. The Problem with Arming Teachers ............................................ -

Public Health Approach to Mass Shootings

The Public Health Approach to Preventing Mass Shootings EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Our communities are not acting on obvious warning Public health systems are effective at detecting those signs that regularly occur before mass shootings that, at risk of violent behavior because they are expert if acted upon, could allow us to collectively and reliably at getting close to, and being trusted by persons at prevent mass shooting events from occurring. These high risk, allowing these health systems to interrupt warning signs are regularly detected on social media violence and change behaviors. posts, as well as parent, student, neighbor and other’s concerns, complaints and reports. Public Health For example, prior to the tragedy on February 14 in Adds More Prevention Parkland, Florida, a number of community members knew that the young man had serious problems and • Proactive detection of warning signs had even signaled his intentions1 - just as family, - trained professionals detecting warning signs coworkers, and neighbors have been aware of - community reporting that is confidential and helpful troubling signs in many other mass shooters in the - connection with schools and other sectors past. In many cases law enforcement has been alerted, yet were unable to stop the shooter from acting as • Personalized connection to highest risk no illegal act had occurred. In some cases, absent an obvious crime, people have not reported the troubling • Tracking & follow up with highest risk warning signs, particularly when it would mean potentially causing harm