The Whale and the Region: Orca Capture and Environmentalism in the New Pacific Northwest Jason Colby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captive Orcas

Captive Orcas ‘Dying to Entertain You’ The Full Story A report for Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) Chippenham, UK Produced by Vanessa Williams Contents Introduction Section 1 The showbiz orca Section 2 Life in the wild FINgerprinting techniques. Community living. Social behaviour. Intelligence. Communication. Orca studies in other parts of the world. Fact file. Latest news on northern/southern residents. Section 3 The world orca trade Capture sites and methods. Legislation. Holding areas [USA/Canada /Iceland/Japan]. Effects of capture upon remaining animals. Potential future capture sites. Transport from the wild. Transport from tank to tank. “Orca laundering”. Breeding loan. Special deals. Section 4 Life in the tank Standards and regulations for captive display [USA/Canada/UK/Japan]. Conditions in captivity: Pool size. Pool design and water quality. Feeding. Acoustics and ambient noise. Social composition and companionship. Solitary confinement. Health of captive orcas: Survival rates and longevity. Causes of death. Stress. Aggressive behaviour towards other orcas. Aggression towards trainers. Section 5 Marine park myths Education. Conservation. Captive breeding. Research. Section 6 The display industry makes a killing Marketing the image. Lobbying. Dubious bedfellows. Drive fisheries. Over-capturing. Section 7 The times they are a-changing The future of marine parks. Changing climate of public opinion. Ethics. Alternatives to display. Whale watching. Cetacean-free facilities. Future of current captives. Release programmes. Section 8 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix: Location of current captives, and details of wild-caught orcas References The information contained in this report is believed to be correct at the time of last publication: 30th April 2001. Some information is inevitably date-sensitive: please notify the author with any comments or updated information. -

WINTER 2016 / VOLUME 65 / NUMBER 4 Concern—For the Trump Administration

WINTER 2016 / VOLUME 65 / NUMBER 4 concern—for the Trump administration. Prominent transition figures and names floated for key cabinet posts portend a disastrous direction for conservation in America. President- elect Trump says he will “cancel” the Paris climate accord A Letter from the President and approve the Keystone XL oil pipeline. And though the of AWI sins of the sons perhaps cannot be imputed to the father, it is gravely unsettling to see photos of Eric and Donald Jr. posing After perhaps the most disheartening, divisive campaign in proudly with lifeless “trophies”—a leopard and an elephant modern memory, the votes have been tabulated. Next year, among them—that were gunned down on safari. Meanwhile, a new administration will plant its flag in Washington, DC. we anticipate another Congress in which many of the most A new Congress will convene. A new era will begin for the powerful remain fixated on eroding or erasing hard-won legal citizens of America and, by extension, the citizens of the protections for animals. world affected by American policy. And so, we must redouble our efforts. The Animal Welfare The same can be said for the world’s animals. What happens in Institute will work on the ground, in court, and with Washington has ramifications for wild and domestic animals humanitarians in Congress and the executive branch to see across the country and throughout the world. Ideally, therefore, that animal suffering is addressed and alleviated, that what has an incoming administration would recognize the need to been gained will not be lost. protect biodiversity, take a moral stand against senseless cruelty in animal agriculture and other commercial sectors, and It will be difficult. -

Journal for Critical Animal Studies

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies Special issue Inquiries and Intersections: Queer Theory and Anti-Speciesist Praxis Guest Editor: Jennifer Grubbs 1 ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD GUEST EDITOR Jennifer Grubbs [email protected] ISSUE EDITOR Dr. Richard J White [email protected] EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE Dr. Matthew Cole [email protected] Vasile Stanescu [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas [email protected] Dr. Richard Twine [email protected] Dr. Richard J White [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Lindgren Johnson [email protected] Laura Shields [email protected] FILM REVIEW EDITORS Dr. Carol Glasser [email protected] Adam Weitzenfeld [email protected] EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For more information about the JCAS Editorial Board, and a list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board, please visit the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 2 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD ............................................................................................................. 2 GUEST EDITORIAL .............................................................................................................. 4 ESSAYS From Beastly Perversions to the Zoological Closet: Animals, Nature, and Homosex Jovian Parry ............................................................................................................................. -

The Whale, Inside: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada* Katie Sykes**

The Whale, Inside: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada* Katie Sykes** Canada has just passed a law making it illegal to keep cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in captivity for display and entertainment: the Ending the Captivity of Whales and Dolphins Act (Bill S-203). Only two facilities in the country still possess captive cetaceans: Marineland in Niagara Falls, Ontario; and the Vancouver Aquarium in Vancouver, British Columbia. The Vancouver Aquarium has announced that it will voluntarily end its cetacean program. This article summarizes the provisions of Bill S-203 and recounts its eventful journey through the legislative process. It gives an overview of the history of cetacean captivity in Canada, and of relevant existing 2019 CanLIIDocs 2114 Canadian law that regulates the capture and keeping of cetaceans. The article argues that social norms, and the law, have changed fundamentally on this issue because of several factors: a growing body of scientific research that has enhanced our understanding of cetaceans’ complex intelligence and social behaviour and the negative effects of captivity on their welfare; media investigations by both professional and citizen journalists; and advocacy on behalf of the animals, including in the legislative arena and in the courts. * This article is current as of June 17, 2019. It has been partially updated to reflect the passage of Bill S-203 in June 2019. ** Katie Sykes is Associate Professor of Law at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia. Her research focuses on animal law and on the future of the legal profession. She is co-editor, with Peter Sankoff and Vaughan Black, of Canadian Perspectives on Animals and the Law (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2015) the first book-length jurisprudential work to engage in a sustained analysis of Canadian law regulating the treatment of non-human animals at the hands of human beings. -

Secretary of Labor V. Seaworld of Florida, LLC, Docket No. 10-1705

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH REVIEW COMMISSION 1924 Building - Room 2R90. 100 Alabama Street. S.W. Atlanta. Georgia 30303-3104 Secretary of Labor, Complainant v. OSHRC Docket No. 10-1705 SeaWorld of Florida, LLC, Respondent. Appearances: John A. Black, Esquire and Tremelle Howard-Fishburne, Esquire Office of the Solicitor, U.S. Department of Labor, Atlanta, Georgia For Complainant Carla J. Gunnin Stone, Esquire Constangy, Brooks & Smith, LLC, Atlanta, Georgia For Respondent Karen C. Dyer, Esquire and Jon L. Mills, Esquire Boies, Schiller & Flexner, LLP, Orlando, Florida For Intervenor Before: Administrative Law Judge Ken S. Welsch DECISION AND ORDER SeaWorld of Florida, LLC, is a marine animal theme park in Orlando, Florida. Although it features several different species of animals, killer whales are SeaWorld's signature attraction. The killer whales perform in shows before audiences at Shamu Stadium. On February 24, 2010, SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau was interacting with Tilikum, a 29 year-old male killer whale, in a pool at Shamu Stadium. Ms. Brancheau reclined on a platform located just a few inches below the surface of the water. Tilikum was supposed to mimic her behavior by rolling over onto his back. Instead, Tilikum grabbed Ms. Brancheau and pulled her off the platform and into the pool. Ms. Brancheau died as a result of Tilikum' s actions. 1 In response to media reports of Ms. Brancheau's death, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) compliance officer Lara Padgett conducted an inspection of SeaWorld. Based on Ms. Padgett's inspection, the Secretary issued three citations to SeaWorld on August 23, 2010. -

Govt to NAME, Shame Slack Officials AS Streets Deluged

SUBSCRIPTION SUNDAY, MARCH 26, 2017 JAMADA ALTHANI 28, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Travellers to Troubled EU Purchase of Arrogate Germany urged renews vows 777-300ERs a wins Dubai to apply for on 60th ‘game-changer’ World Cup visas early5 anniversary7 for21 KAC thriller20 Govt to name, shame slack Min 16º Max 27º officials as streets deluged High Tide 11:27 & 22:46 Low Tide Fire Dept uses boats, divers to rescue trapped motorists 05:08 & 17:01 40 PAGES NO: 17179 150 FILS KUWAIT: The minister of public works announced yes- terday that a panel would be formed to examine why Weary flyers some roads and public places were swamped with rain- water late Friday. Civil servants who were slack and shrug as laptop failed to deal with the situation “would be exposed” along with those who were responsible for the wide- ban takes off scale flooding witnessed in Kuwait due to heavy rain, Abdulrahman Al-Mutawa indicated. DUBAI: A controversial ban on carry-on laptops and In a statement to Kuwait News Agency (KUNA), tablets on flights from the Middle East to the United Mutawa said he held an emergency meeting with offi- States and Britain went into effect yesterday - with cials of his department to discuss the causes of the less fanfare and frustration than expected. From problem. A special and neutral committee will be Dubai to Doha, passengers on dozens of flights formed to examine the causes that led to accumulation checked in their electronic devices, many shrugging of huge volumes of water on roads and public squares off the measure as yet another inconvenience of in the country, he added, indicating that names of the global travel. -

AN ALTERNATIVE PARADIGM for CONSERVATION EDUCATION: INNOVATIONS in the PUBLIC PRESENTATION of KILLER WHALES at the VANCOUVER AQUARIUM by ELIN P

AN ALTERNATIVE PARADIGM FOR CONSERVATION EDUCATION: INNOVATIONS IN THE PUBLIC PRESENTATION OF KILLER WHALES AT THE VANCOUVER AQUARIUM by ELIN P. KELSEY B.Sc. (Zoology), University of Guelph, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULHLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES in the Faculty of EDUCATION (SCIENCE EDUCATION) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July, 1994 ©ELIN P. KELSEY, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Science Education The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date July 29, 1994 DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Conservation is the number one goal of modern zoos and aquaria. Public education is the primary means through which zoos and aquaria attempt to fulfill their conservation goal. Yet, nearly two decades after its initial adoption, conservation education fails to be effectively translated into practice. This thesis argues that the entertainment paradigm in which zoos and aquaria have traditionally operated is at odds with their contemporary goal of conservation education, thus continued adherence to this entertainment paradigm prevents zoos and aquaria from effectively implementing conservation education. -

Let Stanley Park Be!

Just Say No! Let Stanley Park Be! PROTECT NATURE: Stanley Park Let Stanley Park Be! Lifeforce/Peter Hamilton Copyright Report to: Vancouver Parks Board Commissioners Mayor Sam Sullivan and Vancouver Council Compiled by: Lifeforce Foundation, Box 3117, Vancouver, BC, V6B 3X6, (604)669-4673; [email protected]; www.lifeforcefoundation.org November 25, 2006 Introduction The Aquarium and Zoo Industry sends anti-conservation messages to get up close with wildlife. Touch, feed and swim with business gimmicks promotes a speciest attitude to dominate and control wildlife. People, Animals and Ecosystems Threatened by Captivity Plans People, animals and ecosystems would be threatened if the Vancouver Aquarium expands again. More animals would be imprisoned and scarce Stanley Park land would be destroyed. The new prisons will costs taxpayers millions of dollars that should be spent on essential services social and environmental protection. The 50th Anniversary of the Vancouver Aquarium marks a legacy of animal suffering. They started the orca slave trade when one orca briefly survived their attempt to harpoon him to use as a model for a sculpture. The resulting removal of 48 Southern Community Orcas decimated their families. There has been at least 29 deaths of cetaceans and numerous other death and suffering of wildlife. The expansion is sad news because imprisonment of sentient creatures will continue. When the beluga pool was enlarged the promise was that it would be for three but when one died they capture three more. The overcrowding and abnormal aggression lead to some being warehoused in a 50-foot pool for over two years out of public view. -

What the Whale Was: Orca Cultural Histories in British Columbia Since 1964

WHAT THE WHALE WAS: ORCA CULTURAL HISTORIES IN BRITISH COLUMBIA SINCE 1964 by Mark T. Werner B.A., St. Olaf College, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2010 © Mark T. Werner, 2010 Abstract My thesis argues that indigenous historical narratives demonstrate an understanding of the killer whale subjectivity that settler society is only beginning to comprehend. Set in the late 20th century, a period when human relationships with killer whales were undergoing a fast-paced reconfiguration, my research explores the spaces of orca-human encounter in regards to three killer whales: Moby Doll, the world’s first orca held in captivity; Skana, the first orca showcased at the Vancouver Aquarium; and Luna, the orphaned orca of Nootka Sound. Each example speaks to the common process by which humans project culturally-specific narratives and beliefs onto the lives of the whales. In the case of Moby Doll, I argue that the dominant discourse regarding the whale conformed to a strict gender script that functioned to silence other narratives and realities of Moby’s captivity. In my following chapter, I look at how the close relationship between Paul Spong and Skana inspired the scientist to abandon his most fundamental assumptions about orcas in favor of new affordances for orca subjectivity. Furthermore, I argue that the scientific research of John Lilly, a scientist who had a similar conversion experience with dolphins, inspired whole new literatures and imaginations of intelligent dolphins in New Age culture. -

Keto & Tilikum Express the Stress of Orca Captivity

Keto & Tilikum Express the Stress of Orca Captivity by John S. Jett Visiting Research Professor Stetson University [email protected] & Jeffrey M. Ventre Physician New Orleans, LA, USA [email protected] February 2011 Manuscript Submitted to The Orca Project Appendix A Compiled by John Kielty Appendix B Adapted by the Authors Keto & Tilikum Express the Stress of Orca Captivity The practice of keeping killer whales in captivity has proven to be detrimental to the health and safety of animals and trainers alike. On Christmas Eve, 2009, trainer Alexis Martinez was killed by a male captive bred orca named Keto, who was on loan from Sea World to a facility called Loro Parque, in the Canary Islands, Spain. Two months later, on 24 February 2010, trainer Dawn Brancheau was killed by Tilikum, an animal involved with two previous human fatalities. Medical Examiner (ME) reports described massive trauma to both Dawn and Alexis. Neither death was accidental. While orca captivity generates large profits for companies like Sea World (SW), life in a shallow concrete tank is greatly impoverished compared to the lives of their free-ranging counterparts. Trainer deaths, whale deaths, and numerous documented injuries to both trainers and whales provide evidence of several key issues related to killer whale captivity. Tilikum is representative of the many social and health issues plaguing captive orcas. Typically spending their entire lives within tight family groupings, orcas captured from the wild, including Tilikum, have been traumatically extracted from the security, comfort and mentoring which these groupings provide. Captured animals are confined to small, acoustically-dead, concrete enclosures where they must live in extremely close proximity to other whales with which they often share no ancestral, cultural or communication similarities. -

2020 Volume 51

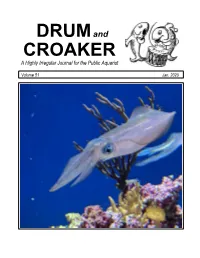

DRUM and CROAKER A Highly Irregular Journal for the Public Aquarist Volume 51 Jan. 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 51, 2020 2 Drum and Croaker ~50 Years Ago Richard M. Segedi 3 The Culture of Sepioteuthis lessoniana (Bigfin Reef Squid) at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Alicia Bitondo 15 Comparison of Mean Abundances of Ectoparasites from North Pacific Marine Fishes John W. Foster IV and Tai Fripp 39 A Review of the Biology of Neobenedenia melleni and Neobenedenia girellae, and Analysis of Control Strategies in Aquaria Barrett L. Christie and John W. Foster IV 86 Trends in Aquarium Openings and Closings in North America: 1856 To 2020 Pete Mohan 99 Daphnia Culture Made Simple Doug Sweet 109 Hypersalinity Treatment to Eradicate Aiptasia in a 40,000-Gallon Elasmobranch System at the Indianapolis Zoo Sally Hoke and Indianapolis Zoo Staff 121 German Oceanographic Museum, Zooaquarium de Madrid and Coral Doctors Cluster to Develop a Project on Training of Locals on Reef Rehabilitation in the Maldives Pablo Montoto Gasser 125 Efficacy of Ceramic Biological Filter Bricks as a Substitute for Live Rock in Land-Based Coral Nurseries Samantha Siebert and Rachel Stein 132 AALSO & RAW Joint Conference Announcement for 2020 Johnny Morris' Wonders of Wildlife National Museum and Aquarium in Springfield, Missouri, USA, March 28 - April 1 136 RetroRAW 2019 Abstracts The Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Columbus, OH, USA, May 13-17 162 A Brief Guide to Authors Cover Photo: Bigfin Reef Squid - Alicia Bitondo Interior Gyotaku: Bruce Koike Interior Line Art Filler: Craig Phillips, D&C Archives Drum and Croaker 51 (2020) 1 DRUM AND CROAKER ~50 YEARS AGO Richard M. -

Political Discussion Group Packet January 2017

POLITICAL DISCUSSION GROUP PACKET JANUARY 2017 Wild Elephants Live Longer Than Their Zoo Counterparts Maryann Mott for National Geographic News December 11, 2008 Wild elephants in protected areas of Africa and Asia live more than twice as long as those in European zoos, a new study has found. Animal welfare advocates have long clashed with zoo officials over concerns about the physical and mental health of elephants in captivity. PHOTO: Elephant Shuns Jumbo Treadmill (May 19, 2006) More U.S. Zoos Closing Elephant Exhibits (March 2, 2006) VIDEO: Abused Elephants Saved (March 26, 2008) British and Canadian scientists who conducted the six-year study say their finding puts an end to that debate once and for all. "We're worried that the whole system basically doesn't work and improving it is essential," said lead author Georgia Mason, a zoologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. Obesity and stress are likely factors for the giant land mammals' early demise in captivity, she said. Until these problems are resolved, the authors are calling for a halt to importing wild elephants and breeding them in facilities unless an institution can guarantee long, healthy lives for its elephants. The study will be published tomorrow in the journal Science. (Related: "Zoo Life Shortens Elephant Lives in Europe, Study Says" [October 25, 2002].) Wild and Long-Lived Mason and colleagues looked at data from more than 4,500 wild and captive African and Asian elephants. The data include elephants in European zoos, which house about half of the world's captive elephants; protected populations in Amboseli National Park in Kenya; and the Myanma Timber Enterprise in Myanmar (Burma), a government-run logging operation where Asian elephants are put to work.