Five Years on with the first Entry Taking Gcses Is an Opportune Moment to Take Stock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper School

1 Editor’s Note Welcome to the first edition of Liverpool College’s Middle School Magazine College Column. Over the past few months, I have been working with both Year 8 Butler’s and Year 8 Brook’s during Thursday activity sessions to bring you this inaugural issue. Firstly, I would like to applaud the efforts of all pupils that were involved in the making of this very first version of College Column. I am extremely grateful for the hard work and dedication demonstrated by the pupils of both Butler’s and Brook’s during this process. Moreover, I would like to thank Mr Cartwright for arranging this activity and allowing pupils to become creative outside of the classroom. It has been a privilege to see pupils develop original ideas into complete articles. Additionally, I am very excited to begin working on future editions of College Column with the other Year 8 forms throughout the remainder of the academic year. If you’re in a Year 8 form, get thinking of future articles that you would like to include in your personal issue of College Column. Finally, to you the reader, thank you for taking the time to read the very first College Column. This version of College Column puts particular emphasis on Liverpool College’s recent (and quite frankly fantastic GCSE results) in addition to providing advice for our new Year 7 pupils, a range of original pieces of creative writing and information about the impending school play Bye, Bye Birdie. There are a range of puzzles and activities to complete in the magazine. -

Broad Square Bulletin Issue 3 – Friday 21St September

Broad Square Bulletin Issue 3 – Friday 21st September Message from the Headteacher . This week it has been wonderful to welcome so many parents and carers of children in Y1-Y6 to our 'Meet the Teachers' sessions. We hope that those who were able to attend really appreciated hearing about the expectations for their child's year ahead. I know that morning meetings can sometimes be difficult to attend, especially if you work so we have uploaded the presentations onto our website. Visit the parents page on the information tab to access them. Y4 had an insightful trip this week which included a guided tour of Liverpool with one of the city's Blue Badge Guides. They have learnt such a lot about the history of our wonderful city which will underpin the rest of their topic this term. The guide complemented our children on their outstanding behaviour and he was also very impressed in their eagerness to learn and have a go at all of the activities. Thank you again for your efforts with getting children into school every day and on time. We had 2 classes last week with 100% attendance, which is fantastic. A letter with all the key dates for the term ahead will be sent to you next week and we will also be putting them onto our website. These will include any further opportunities for family learning. I look forward to seeing as many of you as possible next Friday for the Macmillan coffee morning too! Have a lovely weekend, Mrs. V. Corbett Events next week (24th-28th September) Upcoming Events Thurs. -

British Physics Olympiad 2008 Awards by School

British Physics Olympiad 2008: Awards School Surname First Name Award Abbey College, Cambridge Sun Jing Gold Chen Hu Gold Zhao Yue Gold Zhang Yuewen Gold Tan Guo Wen Silver Do Dinh Silver Xu Zengmin Bronze I Long Pham Nam Bronze I Zhou Yang Bronze I Yen Vu Thi Hai Bronze II Huo Zhao Bronze II Abingdon School, Oxon. Desmond Harry Gold Ai Yuzhao Gold Middleton Tim Gold Loh Howard Silver Morgan John Silver Kong Timothy Silver Coldwell Michael Silver Ganin Leonid Bronze I Tao Jun Bronze I Delo Joseph Bronze I Cheung Kevin Bronze II Lau Jonathan Bronze II Baker Sean Bronze II Long Edmund Bronze II Ko Mephis Bronze II White Stuart Commendation Adams Grammar School, Shropshire Oliver Ian Silver Lunt Alexander Bronze I Wright Jonathan Bronze I Millar Richard Bronze I Phillips Joe Bronze II Wakefield Andrew Bronze II Kirkpatrick David Bronze II White Ben Bronze II Stevens Liam Bronze II Rutherford Ian Bronze II Morris David Commendation Wrigley Lewis Commendation Shotton Chris Commendation Morris Gareth Commendation Odeneye Sayo Commendation Alcester Grammar, Warcs. Michaelis Tom Bronze I Zolman David Commendation Lawler Jamie Commendation Francis - Jones Jamie Commendation Dent Michael Commendation Austin Dan Commendation Rowlinson Josh Commendation Davies Luke Commendation 11 January 2008 Page 1 of 19 School Surname First Name Award Arnold School, Lancs. Nelson Andrew Silver Parekh Viren Bronze II Aylesbury Grammar School, Bucks. Li Ben Gold Chaushev Alex Commendation Bablake School, Coventry Ho Dan Bronze I Hall Matthew Bronze II Bosher Bradley Bronze II Seeley Mark Bronze II Berd Tom Bronze II Bancroft's School, Essex Aggarwal Prenau Silver Chandrakumaran Maiuran Bronze I Regueiro Alexander Bronze II Ranjan Uthishtan Bronze II Leahe Adam Bronze II Carter Samantha Bronze II Cornhill Emily Bronze II Armstrong James Bronze II Tay Weparn Commendation Barnard Castle School, Northumberland Moss Andrew Bronze II Almond James Bronze II Barton Court G. -

National Student Assessment Policies In

FIVE YEARS ON Open Access to Independent Education Alan Smithers and Pamela Robinson Centre for Education and Employment Research University of Buckingham On behalf of the Sutton Trust and the Girls’ Day School Trust Contents Foreword, Sir Peter Lampl, Chairman of the Sutton Trust i Executive Summary ii Latest Developments, Barbara Harrison, Chief Executive of the GDST iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Admissions 3 3. Progress and Achievement 11 4. Views of the Pupils 16 5. Views of the Parents 24 6. Impact on School 29 7. Evaluation 38 References 41 Foreword When I came back to the UK in the mid-Nineties, the educational landscape had changed considerably. The proportion of state school students at my old university, Oxford, had fallen from around two-thirds when I was there in the late Sixties, to under a half; and my old school, Reigate Grammar, where all places had been free, was now – along with many other former grammar and direct grant schools – fully fee-paying, closed to the vast majority of children on its doorstep. It soon became clear to me that these examples were symptomatic of a wider and significant decline in the opportunities available to bright children from non-privileged backgrounds. That was my motivation for establishing the Sutton Trust and joining with the Girls’ Day School Trust to introduce Open Access, or needs-blind admission as it is known in the US, to The Belvedere School one of the GDST’s 26 high performing schools. We wanted the School’s first-rate teaching and ethos of excellence to be available to all girls in its local area, with every place allocated on the basis of merit alone, not ability to pay. -

18124 Dfes 400 Academies AW.Indd

PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES 400 Academies Prospectus for Sponsors and Local Authorities Contents Why Academies? 03 Transforming Educational Opportunity 04 Sponsors 08 Local Authorities & Academies 12 School Competitions 14 Governance 15 Buildings 17 02 400 Academies: Prospectus for Sponsors and Local Authorities PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Mossbourne Academy Mossbourne Academy is built on the site of The Academy is by any criteria a great success. Hackney Downs School, which was closed in When inspected by OFSTED in September 2006, 1995 as one of the worst schools in the country. it received a grade 1 (outstanding) on every The Academy serves the same diverse local single measure. Inspectors described themselves community, which has high levels of deprivation as “enthralled”, and concluded that: – with over 40% of the students receiving free “ Mossbourne Community Academy is an school meals, but the contrast between the outstanding school because it achieves its two schools could not be greater. mission… Within a very short time it has demonstrated that it is changing the lives Sponsored by local businessman, the late of pupils for the better.” Sir Clive Bourne, Mossbourne opened in an award-winning new building in September See: www.mossbourne.hackney.sch.uk 2004. Mossbourne’s Principal, Sir Michael Wilshaw, is a National Leader of Education and trains other academy leaders. 400 Academies: Prospectus for Sponsors and Local Authorities 03 Why Academies? Academies are all-ability independent state schools with a mission to transform education where the status quo is simply not good enough. -

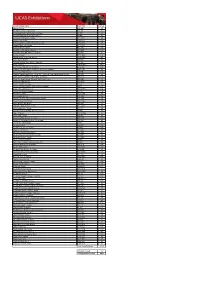

School/College Name Post Code Group 9629 9826

School/college name Post code Group Abacus College L15 4LE 10 All Saints Catholic High School L33 8XF 42 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College L9 7BF 125 Archbishop Blanch C of E High School L76HQ 80 Bebington High Sports College CH632PS 30 Benton Park School LS19 6LX 130 Birkenhead School, Birkenhead, Merseyside CH43 2JD 47 Bishop Heber High School SY14 8JD 125 Bolton VI Form College BL3 5BU 200 Broadgreen International School L13 5UQ 137 Broughton Hall High School, Liverpool L12 9HJ 85 Burnley College BB12 0AN 150 Calday Grange Grammar School CH48 8GG 228 Calderstones School L183HS 117 Cardinal Heenan High School, Liverpool L12 9HZ 65 Carmel College WA10 3AG 779 Castell Alun High School, Wrexham LL12 9HA 106 Cheslyn Hay Sport and Community High School, Walsall WS6 7JQ 93 Chesterfield High School L239YB 100 Childwall Sports and Science Academy - (formerly A Specialist Sports School) L15 6XZ 50 Christ the King Catholic High School, Southport PR8 4EX 100 Christ The King Catholic School & Sixth Form Centre PR8 4EX 90 Christleton High School CH3 7AD 190 City of Liverpool College L77JA 11 City of Liverpool College, The Learning Exchange L35TP 111 Cowley International College WA10 6PN 130 Deyes High School, Maghull L31 6DE 150 Ellesmere College SY12 9AB 80 Formby High School L37 3HW 150 Gateacre Community Comprehensive School L25 2RW 50 Great Sankey High School WA5 3AA 120 Grove School, Shropshire TF9 1HF 75 Hawarden High School, Deeside CH5 3DN 88 Holly Lodge Girls College L12 7LE 40 Holy Family Catholic High School, Liverpool L234UL 53 -

Dfe Number School Name Address Admitting Authority PAN Oversubscribed Places Offered Waiting List Numbers Distance Tie Break

DfE Number School Name Address Admitting Authority PAN Oversubscribed Places Offered Waiting List Numbers Distance Tie Break Max Distance Miles 3414000 King's Leadership Academy, Liverpool King's Leadership Academy, Dingle Vale, Liverpool, L8 9SJ OAA 150 No 150 3414404 Holly Lodge Girls' College Holly Lodge Girls College, Mill Lane, West Derby, Liverpool, L12 7LE Community 189 No 196 3414420 Fazakerley High School Fazakerley High School, Sherwoods Lane, Liverpool, L10 1LN Community 180 No 176 3414425 Broadgreen International School, A Tech College Queens Drive, West Derby, Liverpool, L13 5UQ OAA 210 No 205 3414429 Gateacre Community Comprehensive School Hedgefield Road, Liverpool, L25 2RW Community 240 No 205 3414797 The De La Salle Academy Carr Lane East, Liverpool, L11 4SG OAA 120 No 96 3415400 St Francis Xavier's College Beaconsfield Road, Liverpool, L25 6EG OAA 215 No 211 3416908 The Academy of St Nicholas' Enterprise South Liverpool Academy, Horrocks Avenue, Liverpool, L19 5PF OAA 180 No 143 3414001 Childwall Sports & Science Academy Queens Drive, Wavertree, Liverpool, L15 6XZ OAA 180 Yes 180 33 3414004 Liverpool College Molyneux Road, Mossley Hill, L18 8BE OAA 145 Yes 145 314 3414009 The Academy of St Francis Assisi The Academy Of St Francis Of Assisi, Gardners Drive, Liverpool, L6 7UR OAA 180 Yes 180 22 3414306 West Derby School West Derby School, 364 West Derby Road, Tuebrook, Liverpool, L13 7HQ OAA 180 Yes 180 103 3414421 Alsop High School (A Technology College) Queens Drive, Walton, Walton, Liverpool, L4 6SH Community 270 Yes -

List of North West Schools

List of North West Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abraham Moss Community School Manchester 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Academy@Worden Lancashire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Accrington Academy Lancashire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Accrington and Rossendale College Lancashire Please check your secondary Please check your school. -

AGM 2018 Chairman’S Report

AGM 2018 Chairman’s Report 0151 317 9500 [email protected] nwrfca.org.uk the Volunteer Estate, we have been able Introduction to bring in additional revenue which has not only benefitted the units, facilitating Col Nick Williams, Chairman, NW RFCA the activities on their sites by receiving 30% back, but has enabled those units Reserves and Cadets “valuable and valued” that simply don’t have the marketable estate to raise income. Additionally, we Another financial year has come to an end and as have been able to support some excellent you read this Chairman’s Report we will be coming activities through our entrepreneurial up to the end of month three of this year. The in- outlook – more of which will be covered further into this report – but the multi- year financial pressures last year put a squeeze skilled operative in Cheshire and on our outputs but whilst the fiscal arena is tight we seem to have come Merseyside, and the installation of our away remarkably unscathed from this New Year’s in-year financial 1.1MW solar array at Altcar as well as the battery storage/gas peaking installations pressures. Certainly we are in a better position this year as at the time of both in Altcar and potentially across a the AGM last year we had already been faced with our third in-year cut number of Army Reserve Centres, will within the Grant-in-Aid Army Regional Command allocation; a significant bring in additional revenues to support the reductions of budgets. In addition, reduction was against the Army Cadet Force (ACF) operating grant, as in partnership with Army Headquarters well as other cuts across our funding lines. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 517 28 October 2010 No. 61 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 28 October 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 443 28 OCTOBER 2010 444 5. Iain Stewart (Milton Keynes South) (Con): What House of Commons steps he is taking to ensure the economic sustainability of the rail network. [19916] Thursday 28 October 2010 10. Jake Berry (Rossendale and Darwen) (Con): What steps he is taking to ensure the economic The House met at half-past Ten o’clock sustainability of the rail network. [19921] 12. Karl McCartney (Lincoln) (Con): What steps he PRAYERS is taking to ensure the economic sustainability of the rail network. [19923] [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] The Secretary of State for Transport (Mr Philip Hammond): Recent estimates by the Office of Rail Regulation suggest that the UK railway has costs up to 40% higher than comparable European railways. To Oral Answers to Questions secure a fair deal for passengers and taxpayers in the medium term, we must get the cost base of the railway under control. The Rail Value for Money study led by Sir Roy McNulty will report in the spring, and the TRANSPORT Government will then respond to its recommendations. We have recently completed a consultation on passenger rail franchising, and will publish our response in due The Secretary of State was asked— course. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Pensions Committee, 17/07/2017

Public Document Pack Pensions Committee Date: Monday, 17 July 2017 Time: 6.00 pm Venue: Council Chamber - Birkenhead Town Hall Contact Officer: Pat Phillips Tel: 0151 691 8488 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.wirral.gov.uk AGENDA 1. MEMBERS' CODE OF CONDUCT - DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Members of the Committee are asked to declare any disclosable pecuniary and non pecuniary interests, in connection with any item(s) on the agenda and state the nature of the interest. 2. MINUTES (Pages 1 - 6) To approve the accuracy of the minutes of the meeting held 21 March, 2017. 3. AUDIT FINDINGS REPORT (Pages 7 - 32) 4. STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2016/17 AND LETTER OF REPRESENTATION (Pages 33 - 40) 5. DRAFT ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS (Pages 41 - 124) 6. BUDGET OUTTURN 16/17, FINAL BUDGET 17/18 (Pages 125 - 132) 7. LGPS UPDATE (Pages 133 - 142) 8. POOLING UPDATE (Pages 143 - 146) 9. TRANSPARENCY CODE (Pages 147 - 150) 10. PENSION BOARD ANNUAL REPORT (Pages 151 - 158) 11. ISS GUIDANCE UPDATE (Pages 159 - 162) 12. PENSIONS ADMINISTRATION STRATEGY (Pages 163 - 192) 13. TREASURY MANAGEMENT ANNUAL REPORT (Pages 193 - 196) 14. PLSA CONFERENCE (Pages 197 - 200) 15. FUNDAMENTALS TRAINING (Pages 201 - 204) 16. LGC INVESTMENT SUMMIT (Pages 205 - 214) 17. MTAA UPDATE REPORT (Pages 215 - 218) 18. MONITORING OF INVESTMENT MANDATES (Pages 219 - 222) 19. TPR COMPLIANCE REPORT (Pages 223 - 228) 20. IMWP MINUTES 06/04/17 & 16/06/17 (Pages 229 - 232) 21. EXEMPT INFORMATION - EXCLUSION OF MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC The following items contain exempt information. RECOMMENDATION: That, under section 100 (A) (4) of the Local Government Act 1972, the public be excluded from the meeting during consideration of the following items of business on the grounds that they involve the likely disclosure of exempt information as defined by the relevant paragraphs of Part I of Schedule 12A (as amended) to that Act. -

PRIMARY to SECONDARY School

TRANSFER FROM PRIMARY TO SECONDARY SCHOOl Information for parents September 2021 INTRODUCTION This information booklet is aimed at the parents of children currently in Year 5 who will become eligible from 12th September 2020 to make their secondary applications for Year 7 places starting in September 2021. This information booklet outlines what will happen and gives you guidance about how you can get more information about schools and advice about how to apply for school places. From 12th September you are then able to make your school preferences application at liverpool.gov.uk/admissions where there is further information and guidance posted online. CHOOSING A SCHOOL The Liverpool city council website includes the composite prospectus admissions information spread across its webpages at liverpool.gov.uk/admissions This includes important information about how to apply to schools; what criteria are used to allocate places if a school gets more applications than it has places available and how places were allocated in the previous year. Before expressing a preference for a school it is important that you understand the school’s admission policy and know whether or not the school was oversubscribed in the previous year. By using this information you can assess your child’s chances of gaining a place in the school. In addition to the composite prospectus admissions information online at liverpool.gov.uk/admissions there are several other sources of information that you can use to find out more about schools, these include the following: • School Open Evenings. (Please see Open Evening section within this booklet for further details) • School websites • School Admissions Team (Contact details can be found in the Contact Points section in this information booklet).