Lantau Tomorrow Vision: to Reclaim Or Not to Reclaim?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Hong Kong Stopover

HONG KONG STOPOVER Why not break up your trip to Europe or America with an exciting Hong Kong stopover? Experience a taste of Asia’s World City in just 48 or 72 hours... Fast Facts Must do’s in Hong Kong Geography - situated on the south-eastern coast Attractions of China. Hong Kong is comprised of Hong Kong • The Big Buddha Island, Kowloon, New Territories and over 260 • Star Ferry outlying islands. • HK Disneyland • Street Markets Currency - Hong Kong dollars (HK$) • The Peak Electricity - 220V/50Hz UK plug Day Tours • Big Bus Tours Visas - Australian and New Zealand passport • Hong Kong Island Tour holders DO NOT require a visa for stays up to 90 • Victoria Harbour Cruise days in Hong Kong • Hong Kong Foodie Tours Language - Cantonese, Mandarin, English Dining • Dim sum • Chinese BBQ Transport • Fusion • Fine dining Airport Express Link • Local snacks One of the world’s leading Airport railway systems, offers you a swift and inexpensive trip Shopping between Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) Shopping areas and either Kowloon (22 mins) or Hong Kong • Hong Kong Island - Station (24 mins) Central, Causeway Bay • Kowloon - Tsim Sha Tsui, Single ticket cost - HK$100 (Kowloon) or HK$110 Nathan Road (HK Island) Malls & Department stores Return ticket cost - HK$185 (Kowloon) or HK$205 • Hong Kong Island - IFC Mall, Times (HK Island) Square • Kowloon - Harbour City Octopus Card • Lantau Island - Citygate Outlets This is an electronic fare card accepted on most public transport, most fast food chains and stores. Street Markets Can be purchased at any MTR station, Airport • Hong Kong Island - Stanley Express and Ferry Customer Service. -

G.N. (E.) 266 of 2021 PREVENTION and CONTROL of DISEASE

G.N. (E.) 266 of 2021 PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF DISEASE (COMPULSORY TESTING FOR CERTAIN PERSONS) REGULATION Compulsory Testing Notice I hereby exercise the power conferred on me by section 10(1) of the Prevention and Control of Disease (Compulsory Testing for Certain Persons) Regulation (the Regulation) (Chapter 599, sub. leg. J) to:— Category of Persons (I) specify the following category of persons [Note 1]:— (a) any person who had been present at Citygate (only the shopping mall is included), 18–20 Tat Tung Road & 41 Man Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island, New Territories, Hong Kong in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time during the period from 10 April to 26 April 2021; (b) any person who had been present at Zaks, Shop G04 on G/F & Shop 103 on 1/F, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, New Territories, Hong Kong in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time during on 11 April 2021; (c) any person who had been present at Novotel Citygate Hong Kong, 51 Man Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island, New Territories, Hong Kong in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time during the period from 10 April to 11 April 2021; (d) any person who had been present on the following premises in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time on 21 April 2021:— (1) 13/F, Cameron Commercial Centre, 458–468 Hennessy -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

Right to Adequate Housing There Were No Recommendations Made on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKSAR) in the Second UPR Cycle

Right to Adequate Housing There were no recommendations made on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKSAR) in the Second UPR Cycle. Framework in HKSAR HKSAR is the most expensive city, worldwide, in which to buy a home. Broadly, housing is categorized into; permanent private housing, public rental housing, and public housing. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) has been extended to HKSAR and its implementation is covered under Article 39 of the Basic Law. The middle income group is squeezed by the rocketing prices, relative to low incomes; particularly given that there is no control to prevent public rental rates being set against the wider commercial property market. The crisis in the affordability of housing in Hong Kong has been noted by successive Chief Executives since 2013. For example, the current Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, said in her Policy Address in October 2017 that “meeting the public’s housing needs is our top priority”. However, despite these statements, since 2013 there has been a continued surge in property prices, rental prices and an increase in the number of homeless. Concerns with the lack of affordable and adequate housing were raised by the ICESCR Committee in their 2014 Concluding Observations on HKSAR. Challenges Cases, facts and comments • The government has not taken • Median property prices are 19.4 times the median sufficient action to protect and salary. promote the right to adequate housing • In the years 2007-2016, property prices in HKSAR under Article 11(1) of ICESCR, including increased by 176.4%, compared to a 42.9% rise in the right to choose one’s residence the median monthly income. -

Public Housing in the Global Cities: Hong Kong and Singapore at the Crossroads

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 11 January 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202101.0201.v1 Public Housing in the Global Cities: Hong Kong and Singapore at the Crossroads Anutosh Das a, b a Post-Graduate Scholar, Department of Urban Planning and Design, The University of Hong Kong (HKU), Hong Kong; E-mail: [email protected] b Faculty Member, Department of Urban & Regional Planning, Rajshahi University of Engineering & Technology (RUET), Bangladesh; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Affordable Housing, the basic human necessity has now become a critical problem in global cities with direct impacts on people's well-being. While a well-functioning housing market may augment the economic efficiency and productivity of a city, it may trigger housing affordability issues leading crucial economic and political crises side by side if not handled properly. In global cities e.g. Singapore and Hong Kong where affordable housing for all has become one of the greatest concerns of the Government, this issue can be tackled capably by the provision of public housing. In Singapore, nearly 90% of the total population lives in public housing including public rental and subsidized ownership, whereas the figure tally only about 45% in Hong Kong. Hence this study is an effort to scrutinizing the key drivers of success in affordable public housing through following a qualitative case study based research methodological approach to present successful experience and insight from different socio-economic and geo- political context. As a major intervention, this research has clinched that, housing affordability should be backed up by demand-side policies aiming to help occupants and proprietors to grow financial capacity e.g. -

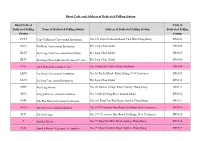

Short Code and Address of Dedicated Polling Station

Short Code and Address of Dedicated Polling Station Short Code of Code of Dedicated Polling Name of Dedicated Polling Station Address of Dedicated Polling Station Dedicated Polling Station Station CCCI Cape Collinson Correctional Institution No. 123 Cape Collinson Road, Chai Wan, Hong Kong DPS101 NKCI Nei Kwu Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS104 HLCI Hei Ling Chau Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS105 HLTC Hei Ling Chau Addiction Treatment Centre Hei Ling Chau Island DPS106 LCK Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre No. 5 Butterfly Valley Road, Kowloon DPS108 LKCI Lai King Correctional Institution No. 16 Wa Tai Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories DPS109 LSCI Lai Sun Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS110 MHP Ma Hang Prison No. 40 Stanley Village Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS111 TFCI Tong Fuk Correctional Institution No. 31 Ma Po Ping Road, Lantau Island DPS112 PSW Pak Sha Wan Correctional Institution No. 101 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS113 PUCI Pik Uk Correctional Institution No. 399 Clearwater Bay Road, Sai Kung, New Territories DPS114 PUP Pik Uk Prison No. 397 Clearwater Bay Road, Sai Kung, New Territories DPS115 S Stanley Prison No. 99 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS116 S(A) Stanley Prison (Category A Complex) No. 99 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS117 Short Code of Code of Dedicated Polling Name of Dedicated Polling Station Address of Dedicated Polling Station Dedicated Polling Station Station SLPC Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre No. 21 Hong Fai Road, Siu Lam, New Territories DPS118 SPP Shek Pik Prison No. 47 Shek Pik Reservoir Road, Lantau Island DPS119 STCI Sha Tsui Correctional Institution No. -

Berthing Guidelines

Berthing Guidelines Endorsed by Pilotage Advisory Committee Marine Department, HKSAR Contents of these Berthing Guidelines are subject to change. Please visit MARDEP Website for updated information. Last PAC endorsement: 11 May 2005 Prepared by Hong Kong Pilots Association Ltd. Berthing Guidelines Updated on 11 May 2005 Chapter: 1 INDEX Chapter Description 1 Index 2 General remarks 3 Pilotage advisory committee 4 Berthing remarks 5 List of important telephone numbers 6 Tugs information 7 Floating docks information 8 Berth/wharf/terminal information 9 Typhoon procedure 10 Miscellaneous 11 Government mooring buoys 12 Berthing guidelines : by location code (Index) Berthing guidelines : by location code 13 Amendment log sheet ** BERTHING GUIDELINES INDEX ** Code Location BUOY Government mooring buoy CCEMENT China Cement Company (TSK) CFT China ferry terminal CLPTSK China light power station (TSK) CMKEN-N China Merchant Kennedy Town north berth CMKEN-S China Merchant Kennedy Town south berth CRC-A China Resources T/Y main berth (A) CRC-B China Resources T/Y west berth (B) CRC-C China Resources T/Y east berth (C) CRC-CW China Resources Chai Wan berth CRC3-TY China Resources T/Y No. 3 berth CTX Caltex T/Y main berth CTX-5 Caltex T/Y No. 5 berth CTX-6A Caltex T/Y No. 6A berth CTX-LPG Caltex T/Y LPG berth ESSO Esso oil terminal main berth ESSO-EL Esso oil terminal electric power wharf EUROASIA Euro-Asia wharf T/Y HKELECT(N) Lamma power station north wharf HKELECT(S) Lamma power station south wharf JBDGA Junk Bay DG anchorage KC1,2,3,5 Kwai Chung -

Privatising Management Services in Subsidised Housing in Hong Kong

The research register for this journal is available at The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.mcbup.com/research_registers http://www.emerald-library.com/ft Privatising Privatising management management services in subsidised housing services in Hong Kong Ling Hin Li and Amy Siu 37 Department of Real Estate and Construction, The University of Received August 1998 Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Revised June 2000 Keywords Tenant, Property management, Housing, Privatization, Hong Kong Abstract Privatisation of services from the public sector is topical currently mainly because of the potential savings and efficiency to be gained. In the aspect of property management, the Hong Kong Housing Authority owns more than 600,000 units of public housing flats and the requirement for good and efficient property management services is enormous. The current policy of privatising these services to the private management agents has proved to be a correct direction in terms of retaining the growth of the public sector, and also improving the level of services to the tenants. While the privatisation scheme might bring in more opportunities for growth of the property management companies in the private sector, it is more important for the government to forge a proper transitional arrangement to switch to full private management in order not to endanger the already low morale in the public sector. 1. Introduction Privatisation is a general term describing a multitude of government initiatives designed to increase the role of the private sector in the provision of the conventional public services. The principles behind privatisation represent an ideology that puts larger emphasis on the efficiency of the market forces than on the public sector. -

SOUTH CHEUNG CHAU ISLAND LANDFILL 10.1 Basic Information Project Title 10.1.1 South Cheung Chau Island Landfill Site (SCCIL) – Marine Site M.5

Extension of Existing Landfills and Identification Scott Wilson Ltd of Potential New Waste Disposal Sites January 2003 10. SOUTH CHEUNG CHAU ISLAND LANDFILL 10.1 Basic Information Project Title 10.1.1 South Cheung Chau Island Landfill Site (SCCIL) – marine site M.5. Nature of Project 10.1.2 The Project would form a new marine based waste disposal site situated on the existing disposal ground for uncontaminated dredged mud situated south of Cheung Chau (see Figure 10.1). 10.1.3 The SCCIL would require construction of an artificial island of approximately 850ha. The site would be designated as a public filling area for the receipt of inert C&D material; once the reclamation is completed, the site would be developed as a landfill for subsequent operation for the disposal of waste. 10.1.4 Construction works would be as described in Part A, Section 3.2. In addition works for SCCIL would include: - Dredging of 20Mcum of underlying muds for seawall construction. Location and Scale of Project 10.1.5 The SCCIL is located approximately 5km south of the western end of Lantau and 3km south of Cheung Chau. The island of Shek Kwu Chau lies 2.5km to the north west. The site coincides with the area used for mud disposal. Seabed levels in this area vary from 10 to 20m below Chart Datum. This site is bound by the SAR boundary to the south and a major shipping channel to the north. 10.1.6 The SCCIL would cover an area of 850ha to an elevation of +6 mPD. -

Lantau Development Work Plan

C&W DC No. 28/2015 Lantau Development Work Plan (2/2015) 2 Outline Planning Department 1. Lantau at Present 2. Development Potential of Lantau 3. Considerations for Developing Lantau 4. Major Infrastructure and Development Projects under Construction / Planning in Lantau 5. Vision、Strategic Positioning、Planning Themes Development Bureau 6. Lantau Development Advisory Committee Lantau at Present 4 Lantau at Present Area: Approx 147sq km (excluding nearby islands & airport) Approx 102sq km (about 70%) within country park area Population : Approx 110 500 (2013 estimate) Jobs: Approx 29 000 (plus approx 65 000 on Airport Island) Discovery Bay Tung Chung New Town Mui Wo Legend Country Park Population Concentration Area 5 Lantau at Present North: Strategic economic infrastructures and urban development East : Tourist hub South & West: Townships and rural areas Development Potential of Lantau 7 Development Potential of Lantau International Gateway Guangzhou International and regional Wuizhou transport hub (to Zhaoqing) Dongguan Converging point of traffic from Guangdong, Hong Kong, Macau Materialize “One-hour Foshan intercity traffic circle”」 Nansha Shenzhen Guangzhou Gongmun Qianhai Zhongshan Dongguan Shenzhen Zhuhai Lantau Hengqin Zhuahi Lantau 8 Development Potential of Lantau Potential for “bridgehead economy” at the Hong Kong Boundary Crossing Facilities Island of Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge (HZMB) Tuen Mun to Chek Lap Kok Link HZMB 9 Development Potential of Lantau Proximity to main urban areas Closer to the CBD on Hong Kong