Resilient Doctoral Students in California: a Reflective Study of the Relation Between Childhood Challenges and Academic Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tt Fall 12 Web.Pub

VOL. 53 No. 3 FALL 2012 Meet Michigan’s winning mini-Spingold squad Editor’s note: A team of five 20-something Ann Arbor players won the 0-1500 mini- Spingold KO, a multi- day limited national championship, at the summer North Ameri- can Bridge Champion- ships in Philadelphia. A month earlier, they also won the Sunday Winners of the mini-Spingold 0-1500 Swiss Teams at the KO Teams: (front) Jin Hu and Jonathan Fleischmann; (back) Max Glick, Zach- Toledo Regional. ary Scherr and Zachary Wasserman. Here are their stories: Jonathan Fleischmann ter. I'm an attorney less than a year out of law school. I'm 24 years old and live in I started playing in 1999 Bloomfield Hills with my fa- (Continued on page 22) ther, two brothers, and a sis- DON’T FORGET TO VOTE The annual election for MBA Board of Directors will be held during the last four days of the October regional. If you cannot be there on one of those days, you can still vote by complet- ing and sending in an absentee ballot. See page 5. Candi- dates’ pictures and statements appear on pages 6 and 7. Michigan Bridge Association Unit #137 2012 VINCE & JOAN REMEY MOTOR CITY REGIONAL October 8-14, 2012 Site: William Costick Center, 28600 Eleven Mile Road, Farmington Hills MI 48336 (between Inkster and Middlebelt roads) 248-473-1816 Intermediate/Newcomers Schedule (0-299 MP) Single-session Stratified Open Pairs: Tue. through Fri., 1 p.m. & 7 p.m.; Sat., 10 a.m. & 2:30 p.m. -

Hall of Fame Takes Five

Friday, July 24, 2009 Volume 81, Number 1 Daily Bulletin Washington, DC 81st Summer North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Hall of Fame takes five Hall of Fame inductee Mark Lair, center, with Mike Passell, left, and Eddie Wold. Sportsman of the Year Peter Boyd with longtime (right) Aileen Osofsky and her son, Alan. partner Steve Robinson. If standing ovations could be converted to masterpoints, three of the five inductees at the Defenders out in top GNT flight Bridge Hall of Fame dinner on Thursday evening The District 14 team captained by Bob sixth, Bill Kent, is from Iowa. would be instant contenders for the Barry Crane Top Balderson, holding a 1-IMP lead against the They knocked out the District 9 squad 500. defending champions with 16 deals to play, won captained by Warren Spector (David Berkowitz, Time after time, members of the audience were the fourth quarter 50-9 to advance to the round of Larry Cohen, Mike Becker, Jeff Meckstroth and on their feet, applauding a sterling new class for the eight in the Grand National Teams Championship Eric Rodwell). The team was seeking a third ACBL Hall of Fame. Enjoying the accolades were: Flight. straight win in the event. • Mark Lair, many-time North American champion Five of the six team members are from All four flights of the GNT – including Flights and one of ACBL’s top players. Minnesota – Bob and Cynthia Balderson, Peggy A, B and C – will play the round of eight today. • Aileen Osofsky, ACBL Goodwill chair for nearly Kaplan, Carol Miner and Paul Meerschaert. -

Chance, Luck and Statistics : the Science of Chance

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Alberta Gambling Research Institute Alberta Gambling Research Institute 1963 Chance, luck and statistics : the science of chance Levinson, Horace C. Dover Publications, Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/41334 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Chance, Luck and Statistics THE SCIENCE OF CHANCE (formerly titled: The Science of Chance) BY Horace C. Levinson, Ph. D. Dover Publications, Inc., New York Copyright @ 1939, 1950, 1963 by Horace C. Levinson All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario. Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 10 Orange Street, London, W.C. 2. This new Dover edition, first published in 1963. is a revised and enlarged version ot the work pub- lished by Rinehart & Company in 1950 under the former title: The Science of Chance. The first edi- tion of this work, published in 1939, was called Your Chance to Win. International Standard Rook Number: 0-486-21007-3 Libraiy of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-3453 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc. 180 Varick Street New York, N.Y. 10014 PREFACE TO DOVER EDITION THE present edition is essentially unchanged from that of 1950. There are only a few revisions that call for comment. On the other hand, the edition of 1950 contained far more extensive revisions of the first edition, which appeared in 1939 under the title Your Chance to Win. One major revision was required by the appearance in 1953 of a very important work, a life of Cardan,* a brief account of whom is given in Chapter 11. -

Practical Slam Bidding Ebook

Practical Slam Bidding ebook RON KLINGER MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR BIG HANDS INTRODUCTION Slam bidding brings an excitement all of its own. The pulse quickens, adrenalin is pumping, it’s all systems go. The culmination can be euphoria when you are successful, misery when the slam fails. The aim of this book is to increase your euphoria-to-misery ratio. Of all the skills in bridge, experts perform worst in the slam area. You do not need to go far to find the reason: Lack of experience. Slams occur on about 10% of all deals. Compare that with 50% for partscores and 40% for games. No wonder players are less familiar with the big hands. Half of the slam hands will be yours, half will go to your opponents. You can thus expect a slam your way about 5% of the time. That is roughly one deal per session. If you play twice a week, you can hope for about a hundred slams a year. Practise on the 120 deals in this book and study them, and you will have the equivalent of an extra year’s training under your belt. Your euphoria ratio is then bound to rise. How to use this ebook This is not so much an ebook for reading pleasure as a workbook. It is ideal for partnership practice but you can also use it on your own. For each set of hands, the dealer is given, followed by the vulnerability. You and partner are the East and West. If the dealer is North, East comes next; if the dealer is South, West is next. -

Roadmap for Resilience: the California Surgeon General's

DECEMBER 09, 2020 Roadmap for Resilience The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health Suggested citation for the report: Bhushan D, Kotz K, McCall J, Wirtz S, Gilgoff R, Dube SR, Powers C, Olson-Morgan J, Galeste M, Patterson K, Harris L, Mills A, Bethell C, Burke Harris N, Office of the California Surgeon General. Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health. Office of the California Surgeon General, 2020. DOI: 10.48019/PEAM8812. OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR December 2, 2020 In one of my first acts as Governor, I established the role of California Surgeon General. Among all the myriad challenges facing our administration on the first day, addressing persistent challenges to the health and welfare of the people of our state—especially that of the youngest Californians—was an essential priority. We led with the overwhelming scientific consensus that upstream factors, including toxic stress and the social determinants of health, are the root causes of many of the most harmful and persistent health challenges, from heart disease to homelessness. An issue so critical to the health of 40 million Californians deserved nothing less than a world-renowned expert and advocate. Appointed in 2019 to be the first- ever California Surgeon General, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris brought groundbreaking research and expertise in childhood trauma and adversity to the State’s efforts. In this new role, Dr. Burke Harris set three key priorities – early childhood, health equity and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress – and is working across my administration to give voice to the science and evidence-based practices that are foundational to the success of our work as a state. -

Slam Bidding Why Bid a Slam? Just Like There Is a Bonus for Being in the Game Level, There Is a Bonus for Being in the Slam Levels

Slam Bidding Why bid a slam? Just like there is a bonus for being in the game level, there is a bonus for being in the slam levels. A small slam is a contract at the 6-level, Bidding and making a small slam is worth 500 bonus points when not vul and 750 bonus points when vul. A grand slam is a contract at the 7-level, Bidding and making a small slam is worth 1000 bonus points when not vul and 1500 bonus points when vul. Decision #1: Do you have enough overall strength? When considering a slam, you have to first decide if your two hands have the power to take 12 or 13 tricks once you get the lead. You can often add your points to the number partner has shown to determine your chances. For "normal", fairly balanced hands, use these guidelines: • To make a small slam (bid of 6) -- you need 33 pts. • To make a grand slam (bid of 7) -- you need 37 pts. You may make a slam with fewer points if your hands have other features to make up for what you lack in high-card strength. These include: • Extra trumps -- you need at least an 8-card fit to bid a suit slam, but stronger fits produce more tricks. You may score an extra trick for each trump you have over 8. • Long, strong side suits -- if you can set up and run a long side suit, the small cards can be as valuable as honors. • Short suits -- once you know you have a trump fit, add in your distribution points to determine your hand's full value. -

The Jacoby 2NT Convention David Bakhshi

English Bridge Useful Conventions by David Bakhshi S Roman Key-Card N O I T N E Blackwood V N O C L IN this series, we will look at several responder also reveals whether he holds the U conventions that have been embraced queen of trumps, the final im portant card F both by the expert community and also by when bidding good slams. E aspiring players looking to develop their S bidding accuracy. The first of these is a How does the 4NT bidder proceed? David Bakhshi U variation on the Blackwood convention, which utilises a bid of 4NT to ask partner While it may seem that having either/or how many aces he holds, to ensure that the responses will be confusing to the 4NT 1 RKCB with spades as trumps; 2 1 or 4 key cards; partnership does not attempt to bid a slam bidder, it will often be the case that he 3 Asking for the spade queen; 4 ♠Q + ♣K. when missing two aces. The traditional will know how many key cards his responses to the Blackwood 4NT enquiry partner has as a result of the number of Asking for kings are: 5 ♣ = 0 or 4 aces; 5 ♦ = 1 ace; 5 ♥ = 2 key cards he possesses himself. If two key aces; 5 ♠ = 3 aces. cards are missing, the enquirer will simply Can the enquirer still ask for kings when sign off by returning to the trump suit at interested in a grand slam? Why have variations developed? the five level. When the partner ship is As with regular Blackwood, the enquirer missing just one key card, he will still be can ask for kings by asking for key cards How many times have you bid a slam that interested in slam; now the enquirer first, then following up with a bid of 5NT. -

Hall of Fame Inducts Five Players

Friday, July 19, 2019 Volume 91, Number 1 Daily Bulletin 91st North American Bridge Championships [email protected] | Editors: Paul Linxwiler, Chip Dombrowski, Sue Munday Henneberger wins Hall of Fame inducts five players At last night’s induction ceremony for the Robot IndividualMartin Henneberger ACBL Hall of Fame, five players became members of Coquitlam BC won the of the Hall’s Class of 2019. Peter Boyd, Bart Summer NABC Robot Bramley and Judi Radin were chosen directly by Individual with a score the Hall of Fame electors for the Open category, of 68.62%. Henneberger while Patty Tucker received the Blackwood Award had been in second place for her contributions to the game, and the late after the first two days by Michael Seamon received the von Zedtwitz Award about 4 percentage points in recognition of his bridge accomplishments. behind Fred Pollack, but Additionally, Curtis Cheek received the Sidney H. Henneberger’s day three score of 67.52% put him Lazard Jr. Sportsmanship Award. over when Pollack could muster only 55.75%. The event was emceed by David Berkowitz. Pollack of Laval QC finished second with 67.31%. The ceremony began with Marc Jacobus Sheng Li of New York presenting Cheek for the sportsmanship honor. won Flight B with 64.52%, “I met Curtis 30 years ago. He’s a great just 0.06% ahead of Day opponent and a great person. He always introduced 2019 Hall of Fame Open inductees: Bart 2 leader John Mayne of himself at the table, and he always smiled, but Bramley, Judi Radin and Peter Boyd. -

Slam Bidding Part I

BETTER BIDDING by BERNARD MAGEE leaps in value because you have a fit. You have 17 high-card points, can add two for your excellent long suit and also two for your singleton (with the long trumps); that makes a total of 21. Your partner’s bid shows 10-12 points so that puts the Slam partnership in the range of 31-33, which certainly has slam potential, and there- fore you should try for slam. A 4♥ bid would finish the auction, so West must Bidding do something else to try to find a slam. We will discuss the conventions availa- Part I ble in the forthcoming two articles. Layout B ♠ A 10 4 2 ♠ K Q J 6 ♥ 9 6 4 N ♥ A K 5 3 W E idding slams is not easy, but of the approach followed in this article, ♦ A 9 7 2 S ♦ K 4 there is no doubt that bidding readers who use this method of evalua- ♣ A8 ♣ K 5 3 B and making a slam is one of the tion should stick with it, and when it sug- great joys of bridge. The first important gests that a slam might be on, they should element in slam bidding is trying to explore its possibility. identify when a slam might be on. Note that although you may have 30 Layout C points between you (or the Losing Trick ♠ A10 ♠ K Q J 6 Count might suggest that a slam is on), ♥ 9 6 4 N ♥ A K 5 3 Basic identification W E but without the necessary controls (aces, ♦ A 9 7 2 S ♦ K 4 Slams are a lot easier to make if you kings, singletons and voids), you may ♣ A 8 4 2 ♣ K 5 3 have a big trump fit, because you can still not be able to make a slam – there make extra tricks by trumping and so do is plenty of checking to be done! not have to rely on high cards alone. -

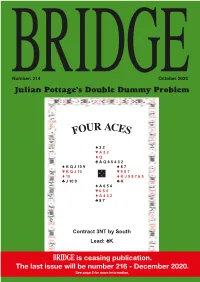

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

Community Park Project Halted by Flood “We Can’T Control Mother Nature,” Says Village Engineer, “We’Re Looking to Mitigate Mother Nature”

VOL. 3, WK. 38 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 $1.00 Community Park project halted by flood “We can’t control Mother Nature,” says village engineer, “We’re looking to mitigate Mother Nature” Floodwaters cover Community park after heavy rains on Friday, September 13. Black Earth Creek never reached flood stage. Construction vehicles and the office were surrounded by water. PHOTO BY JOE BLOCK by JOE BLOCK drological Prediction Center, at “Well, that’s why we work this going to affect my property again. park and additional costs Editor 5.23 feet there is between a 20 with Town & County Engineer- with water coming towards my A new concession stand will percent and 50 percent chance ing,” said village president Pat house?” be built in the middle of the In September the board Black Earth residents are the creek will reach that level Troge. Coyle replied, “You don’t park, on the northern border. It voted to issue approximately concerned that the $749,000 in any year. Village engineer “We’ve seen the amount know.” will be raised several feet above $925,000 in bonds for fund- Community Park project will Brian Berquist confirmed that of water in that area,” said Troge then called for a vote. the ground, above the 100-year ing, with trustee Coyle oppos- not alleviate yearly flooding. is about a one in five to one in Nickolas Bulbolz, the Town & The project was approved by flood level. The smaller ball- ing. The village is applying for Their concerns became reality 10 year flood interval. County engineer in charge of a 4-3 vote. -

Newsletter - Please Take • a Small Increase in the Country Subscription a Look and Let Us Know of Any Issues Or Comments

President's Welcome Money, Money, Money First, many thanks to everyone who responded to our They say that money makes the world go round. proposals for the playing sessions in 2020 by sending Money also makes the bridge club go round! The 2019 back a survey form. We had 55 responses which is Committee has taken the view that both subscriptions about 30% of our membership. and table money should be increased slightly from I know that many of you did not feel affected by 2020, to improve the financial sustainability of the the changes proposed and so did not feel the need to Club. respond - which is fine! So, the Committee has Here’s what’s planned for Subscriptions: assumed that all responses came from people who would like some changes (i.e. who are not completely • A small increase in the Ordinary subscription satisfied with what the Club is currently offering). rate from $100 to $110, with a corresponding We are pleased that so many of you have engaged increase for Ordinary/Second Club members in this process rather than stay quiet. Thank you! The from $77 to $87 full outcome is attached to this newsletter - please take • A small increase in the Country subscription a look and let us know of any issues or comments. rate from $60 to $80, with a corresponding During October, the Committee was busy with the Swiss pairs 5A tournament on 12 October and our Club increase for Country/Second Club members Spring Fling Tournament on 19 October. It was good to from $46 to $57 see a high turnout from our club at these events.