Why We Need to Increase Plant/Insect Linkages in Designed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bumble Bee Clearwing Moths

Colorado Insects of Interest “Bumble Bee Clearwing” Moths Scientific Names: Hemaris thysbe (F.) (hummingbird clearwing), Hemaris diffinis (Boisduval) (snowberry clearwing), Hemaris thetis (Boisduval) (Rocky Mountain clearwing), Amphion floridensis (Nessus sphinx) Figure 1. Hemaris thysbe, the hummingbird clearwing. Photograph courtesy of David Order: Lepidoptera (Butterflies, Moths, and Cappaert. Skippers) Family: Sphingidae (Sphinx Moths, Hawk Moths, Hornworms) Identification and Descriptive Features: Adults of these insects are moderately large moths that have some superficial resemblance to bumble bees. They most often attract attention when they are seen hovering at flowers in late spring and early summer. It can be difficult to distinguish the three “bumble bee clearwing” moths that occur in Colorado, particularly when they are actively moving about plants. The three species are approximately the same size, with wingspans that range between 3.2 to 5.5cm. The hummingbird clearwing is the largest and distinguished by having yellow legs, an Figure 2. Amphion floridensis, the Nessus olive/olive yellow thorax and dark abdomen with sphinx. small patches. The edges of the wings have a thick bordering edge of reddish brown. The snowberry clearwing has black legs, a black band that runs through the eye and along the thorax, a golden/olive golden thorax and a brown or black abdomen with 1-2 yellow bands. The head and thorax of the Rocky Mountain clearwing is brownish olive or olive green and the abdomen black or olive green above, with yellow underside. Although the caterpillar stage of all the clearwing sphinx moths feed on foliage of various shrubs and trees, damage is minimal, none are considered pest species. -

Lafranca Moth Article.Pdf

What you may not know about... MScientific classificationoths Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Photography and article written by Milena LaFranca order: Lepidoptera [email protected] At roughly 160,000, there are nearly day or nighttime. Butterflies are only above: scales on moth wing, shot at 2x above: SEM image of individual wing scale, 1500x ten times the number of species of known to be diurnal insects and moths of moths have thin butterfly-like of microscopic ridges and bumps moths compared to butterflies, which are mostly nocturnal insects. So if the antennae but they lack the club ends. that reflect light in various angles are in the same order. While most sun is out, it is most likely a butterfly and Moths utilize a wing-coupling that create iridescent coloring. moth species are nocturnal, there are if the moon is out, it is definitely a moth. mechanism that includes two I t i s c o m m o n f o r m o t h w i n g s t o h a v e some that are crepuscular and others A subtler clue in butterfly/moth structures, the retinaculum and patterns that are not in the human that are diurnal. Crepuscular meaning detection is to compare the placement the frenulum. The frenulum is a visible light spectrum. Moths have that they are active during twilight of their wings at rest. Unless warming spine at the base of the hind wing. the ability to see in ultra-violet wave hours. Diurnal themselves, The retinaculum is a loop on the lengths. -

Barcoding Life Highlights 2013

Barcoding Life Highlights 2013 BARCODE OF LIFE: a short DNA sequence, from a uniform location on the genome, used for identifying species Snowberry clearwing (Hemaris diffinis) Butterfly bush(Buddleja davidii) DNA barcoding, first developed in 2003, is a Gates Foundation funded high schoolers in Danville, Illinois, and five other U.S. cities to barcode meat standardized approach to identifying species 19 by DNA. Here we focus on recent highlights products—so far, no adulteration has been found. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s Urban Barcode Project had since the Fourth International Barcode of a second successful year, in which the 2013 first prize was Life Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 2011. awarded to students documenting ant diversity in a park adjacent to their school.20 University of Guelph ran an insect DNA barcoding program with 2,000 students at Products need barcoding 60 high schools.21 BioLabs now offers an educational fish Barcoding uncovers continued international mislabeling DNA barcoding kit.22 An online course and a published of fish products, with costs to consumers and threats to compilation of protocols should help disseminate barcoding protected species, and reveals common mislabeling of other expertise.23,24 foods and herbal products.1-3 Barcoding helps detail the enormous illicit global trade in timber and in threatened Diverse support and endangered animals and plants, including products Recent papers and news reports indicate government such as “bushmeat,” meat from wild animals especially in and private funding in dozens of countries around the Africa and Asia, which carries human diseases.4-6 Barcoding world. In the U.S., a $3 million Google Global Impact documents invasive species at ports of entry and crop pests Award to the Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL) in agricultural goods.7,8 is helping establish an endangered species barcode database For these and other applications, certified, affordable, and train biodiversity enforcers in Nigeria, South Africa, and rapid barcode testing services promise great benefits. -

Growing a Wild NYC: a K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum Was Made Possible Through the Generous Support of Our Funders

A K-5 URBAN POLLINATOR CURRICULUM Growing a Wild NYC LESSON 1: HABITAT HUNT The National Wildlife Federation Uniting all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world Through educational programs focused on conservation and environmental knowledge, the National Wildlife Federation provides ways to create a lasting base of environmental literacy, stewardship, and problem-solving skills for today’s youth. Growing a Wild NYC: A K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum was made possible through the generous support of our funders: The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation is a private foundation that supports the arts, housing, basic needs, the environment, and education including professional development and school-day enrichment programs operating in public schools. The Office of the New York State Attorney General and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation through the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Written by Nina Salzman. Edited by Sarah Ward and Emily Fano. Designed by Leslie Kameny, Kameny Design. © 2020 National Wildlife Federation. Permission granted for non-commercial educational uses only. All rights reserved. September - January Lesson 1: Habitat Hunt Page 8 Lesson 2: What is a Pollinator? Page 20 Lesson 3: What is Pollination? Page 30 Lesson 4: Why Pollinators? Page 39 Lesson 5: Bee Survey Page 45 Lesson 6: Monarch Life Cycle Page 55 Lesson 7: Plants for Pollinators Page 67 Lesson 8: Flower to Seed Page 76 Lesson 9: Winter Survival Page 85 Lesson 10: Bee Homes Page 97 February -

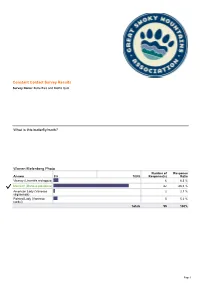

Constant Contact Survey Results What Is This Butterfly/Moth? Warren

Constant Contact Survey Results Survey Name: Butterflies and Moths Quiz What is this butterfly/moth? Warren Bielenberg Photo Number of Response Answer 0% 100% Response(s) Ratio Viceroy (Limenitis archippus) 6 6.3 % Monarch (Danaus plexippus) 82 86.3 % American Lady (Vanessa 2 2.1 % virginiensis) Painted Lady (Vanessa 5 5.2 % cardui) Totals 95 100% Page 1 What is this butterfly/moth? GSMA Photo Number of Response Answer 0% 100% Response(s) Ratio Showy Emerald (Dichorda 5 5.2 % iridaria) Polyphemus Moth 5 5.2 % (Antheraea Polyphemus) Pandorus Sphinx (Eumorpha 2 2.1 % pandorus) Luna Moth (Actias luna) 83 87.3 % Totals 95 100% What is this butterfly/moth? NPS Photo Number of Response Answer 0% 100% Response(s) Ratio Eastern Tiger Swallowtail 80 84.2 % (Papilio glaucus) Giant Swallowtail (Papilio 7 7.3 % cresphontes) Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus 2 2.1 % philenor) Spicebush Swallowtail 6 6.3 % (Papilio troilus) Totals 95 100% Page 2 What is this butterfly/moth? Warren Bielenberg Photo Number of Response Answer 0% 100% Response(s) Ratio Little Wood-Satyr (Megisto 4 4.2 % cymela) Common Buckeye (Junonia 69 72.6 % coenia) Northern Pearly-Eye (Enodia 17 17.8 % anthedon) Io Moth (Automeris io) 5 5.2 % Totals 95 100% What is this butterfly/moth? Warren Bielenberg Photo Number of Response Answer 0% 100% Response(s) Ratio American Snout (Libytheana 9 9.4 % carinenta) Orange-Patched Smoky 26 27.3 % Moth (Pyromorpha dimidiata) Silver-Spotted Skipper 55 57.8 % (Epargyreus clarus) Juvenal's Duskywing 5 5.2 % (Erynnis juvenalis) Totals 95 100% Page 3 What -

Moths & Butterflies of Grizzly Peak Preserve

2018 ANNUAL REPORT MOTHS & BUTTERFLIES OF GRIZZLY PEAK PRESERVE: Inventory Results from 2018 Prepared and Submi�ed by: DANA ROSS (Entomologist/Lepidoptera Specialist) Corvallis, Oregon SUMMARY The Grizzly Peak Preserve was sampled for butterflies and moths during May, June and October, 2018. A grand total of 218 species were documented and included 170 moths and 48 butterflies. These are presented as an annotated checklist in the appendix of this report. Butterflies and day-flying moths were sampled during daylight hours with an insect net. Nocturnal moths were collected using battery-powered backlight traps over single night periods at 10 locations during each monthly visit. While many of the documented butterflies and moths are common and widespread species, others - that include the Western Sulphur (Colias occidentalis primordialis) and the noctuid moth Eupsilia fringata - represent more locally endemic and/or rare taxa. One geometrid moth has yet to be identified and may represent an undescribed (“new”) species. Future sampling during March, April, July, August and September will capture many more Lepidoptera that have not been recorded. Once the site is more thoroughly sampled, the combined Grizzly Peak butterfly-moth fauna should total at least 450-500 species. INTRODUCTION The Order Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) is an abundant and diverse insect group that performs essential ecological functions within terrestrial environments. As a group, these insects are major herbivores (caterpillars) and pollinators (adults), and are a critical food source for many species of birds, mammals (including bats) and predacious and parasitoid insects. With hundreds of species of butterflies and moths combined occurring at sites with ample habitat heterogeneity, a Lepidoptera inventory can provide a valuable baseline for biodiversity studies. -

Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth Hemaris Gracilis

RARE SPECIES OF MASSACHUSETTS Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth Hemaris gracilis Massachusetts Status: Special Concern Federal Status: None DESCRIPTION The Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth (Hemaris gracilis) is a day-flying sphingid moth with a wingspan of 40-45 mm (Covell 1984). Both the forewing and the hind wing are unscaled and transparent except for reddish-brown margins and narrow lines of the same color along the wing veins. Dorsally, the head and thorax are olive green in color when fresh, fading to yellowish-green; the abdomen is banded with green concolorous with the head and thorax, reddish-brown concolorous with the wings, black, and white. The tip of the abdomen has a brush of hair-like scales that are orange medially, flanked with black. Of the three day-flying sphinx moths (Hemaris spp.) in Massachusetts, the Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth is most easily confused with the Hummingbird Clearwing (Hemaris thysbe). However, the Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth has a lateral reddish-brown Photo by M.W. Nelson stripe on the thorax, extending from the eye to the abdomen, that is absent on the Hummingbird Clearwing. POPULATION STATUS The Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth is threatened by habitat loss and fire suppression. Other potential threats include introduced generalist parasitoids, aerial insecticide spraying, non-target herbiciding, and off-road vehicles. RANGE Distribution in Massachusetts 1995-2020 The Slender Clearwing Sphinx Moth is found from based on records in NHESP database Labrador south to New Jersey, and west to Saskatchewan, North Dakota, Minnesota, and Illinois; it also occurs along the Atlantic coastal Sphinx Moth is known to occur in Franklin County plain from New Jersey south to Florida (Tuttle and adjacent northern and western Worcester 2007). -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Reptiles and Amphibians

A good book for beginners is Himmelman’s (2002) book “Discovering Moths’. Winter Moths (2000) describes several methods for By Dennis Skadsen capturing and observing moths including the use of light traps and sugar baits. There are Unlike butterflies, very little fieldwork has a few other essential books listed in the been completed to determine species suggested references section located on composition and distribution of moths in pages 8 & 9. Many moth identification northeast South Dakota. This is partly due guides can now be found on the internet, the to the fact moths are harder to capture and North Dakota and Iowa sites are the most study because most adults are nocturnal, and useful for our area. Since we often identification to species is difficult in the encounter the caterpillars of moths more field. Many adults can only be often than adults, having a guide like differentiated by studying specimens in the Wagners (2005) is essential. hand with a good understanding of moth taxonomy. Listed below are just a few of the species that probably occur in northeast South Although behavior and several physiological Dakota. The list is compiled from the characteristics separate moths from author’s personnel collection, and specimens butterflies including flight periods (moths collected by Gary Marrone or listed in Opler are mainly nocturnal (night) and butterflies (2006). Common and scientific names diurnal (day)); the shapes of antennae and follow Moths of North Dakota (2007) or wings; each have similar life histories. Both Opler (2006). moths and butterflies complete a series of changes from egg to adult called metamorphosis. -

The Pollinator Pantry Ambassadors of the White-Lined Sphinx Moth (Hyles Lineata) St

The Hummingbird Clearwing Moth (Hemaris thysbe) Pollinator Notes: The Pollinator Pantry Ambassadors of The White-lined Sphinx Moth (Hyles lineata) St. Louis County The Snowberry Clearwing Moth (Hemaris diffinis) Nine-Spotted Ladybug Beetle ( Coccinella novmnotata) 314-615-4FUN www.stlouisco.com/ Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) Just who are the "primary pollinators" in the St. Louis Country's pan- try? Let's meet them and their "ambassadors"! These mentioned representatives, our pollinator "ambassadors" were chosen "bee"-cause they are the most familiar, most efficient, most common, least aggressive, sometimes truly unique or just the easiest to recognize "pollen transporters". These pollinators are also the easiest to attract. They are fun to watch visiting our flowers and need a place to call "home" in our Hoverfly landscape. These all can "bee" a welcomed part of our neighbor- ( Toxomerus sp. Diptera) hoods! These are our St. Louis County Pollinator Pantry Ambassadors. The Butterfly and Skipper Ambassadors: The Mason and Leaf Cutter Bee Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) Ambassador: Silver-spotted Skipper ( Epargyreus clarus) Orchard (Osmia lignaria) The gentle orchard bee represents the mason The Nectar Moth Ambassadors: bees and leaf cutter bees (Osmia spp. and Megachile spp.) Silver-spotted Skipper The Snowberry Clearwing Moth Orchard Bee (Osmia lignaria) ( Epargyreus clarus) (Hemaris diffinis) The Honey Bee Ambassador: The Hummingbird Clearwing Moth Western Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) (Hemaris thysbe) The ambassador for honey bees is the busiest of The White-lined Sphinx bees, the western or European honey bee. It is the most (Hyles lineata) common of the species of honey bees. The real value of the honey bees is not the pro- The Hummingbird Ambassador: duction of honey. -

Illustration Sources

APPENDIX ONE ILLUSTRATION SOURCES REF. CODE ABR Abrams, L. 1923–1960. Illustrated flora of the Pacific states. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. ADD Addisonia. 1916–1964. New York Botanical Garden, New York. Reprinted with permission from Addisonia, vol. 18, plate 579, Copyright © 1933, The New York Botanical Garden. ANDAnderson, E. and Woodson, R.E. 1935. The species of Tradescantia indigenous to the United States. Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Reprinted with permission of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. ANN Hollingworth A. 2005. Original illustrations. Published herein by the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Fort Worth. Artist: Anne Hollingworth. ANO Anonymous. 1821. Medical botany. E. Cox and Sons, London. ARM Annual Rep. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1889–1912. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis. BA1 Bailey, L.H. 1914–1917. The standard cyclopedia of horticulture. The Macmillan Company, New York. BA2 Bailey, L.H. and Bailey, E.Z. 1976. Hortus third: A concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. Revised and expanded by the staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. Reprinted with permission from William Crepet and the L.H. Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. BA3 Bailey, L.H. 1900–1902. Cyclopedia of American horticulture. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. BB2 Britton, N.L. and Brown, A. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British posses- sions. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. BEA Beal, E.O. and Thieret, J.W. 1986. Aquatic and wetland plants of Kentucky. Kentucky Nature Preserves Commission, Frankfort. Reprinted with permission of Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. -

Attract Hummingbird Moths & Bumblebee Moths

Attract Hummingbird Moths & Bumblebee Moths Hemaris thysbe Photo © 2004 by Marc Apfelstadt Hemaris diffinis Photo© 2006 by Marc Apfelstadt Hummingbird Moth Bumblebee Moth Plant Native Host plants for eggs and caterpillars: Plant Native Host plants for eggs and caterpillars: Trumpet (or Coral) Honeysuckle trainable vine Trumpet (or Coral) Honeysuckle trainable vine (Lonicera sempervirens) – also a favorite of the (Lonicera sempervirens) Ruby-throated hummingbird Common Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus) Common Chokecherry tree (Prunus virginiana) Dwarf Bush-Honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera) – Wild Black Cherry tree (Prunus serotina) other honeysuckle bushes are invasive/harmful (see www.oipc.info) Plant native nectar plants that bloom during its flight time: April-August. Hummingbird Moths prefer gardens, Plant native nectar plants that bloom during its flight forest edges and meadows. See the How Do I Do This tab time: April-August. Bumblebee Moths prefer gardens, at www.backyardhabitat.info for information about how forest edges, meadows and brushy fields. See the How to create a wildlife habitat. Do I Do This tab at www.backyardhabitat.info for information about how to create a wildlife habitat. Nectar plants are listed in the links for attracting butterflies and attracting bees. A list of vendors to get Nectar plants are listed in the links for attracting you started is in Some Ohio Native Plant Sources. How butterflies and attracting bees. A list of vendors to get to create a forest edge is described in Attract Native you started is in Some Ohio Native Plant Sources. How Songbirds to your Ohio Yard. to create a forest edge is described in Attract Native Songbirds to your Ohio Yard.