JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Transcribed for Orchestra By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frescobaldi Gesualdo Solbiati

Frescobaldi Gesualdo Solbiati FRANCESCO GESUALDI Accordion Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583 -1643) If we think of the theatre as a place in which audiences not only perceive with their eyes and ears, but also their deeper feelings, then the work presented in this recording Dal II Libro di Toccate is in many respects theatrical. The explanation lies in the fact that one of Francesco 1. Toccata I 4’42 Gesualdi’s particular gifts as a performer is his ability to produce sounds that conjure 2. Toccata II 4’44 up the action underlying the music, and indeed evoke the spaces in which the events 3. Toccata III, da sonarsi alla Levatione 8’51 take place. This is particularly noteworthy when performance is actually separated 4. Toccata IV, da sonarsi alla Levatione 6’58 from the reality of visualization. 5. Toccata VIII, di Durezze e Ligature 5’01 The synaesthetic experience underlying vision and visionary perception is arguably one of the fundamental ingredients of the “Second Practice”, or stile moderno, which Dal I Libro di Toccate aimed at engaging the feelings of the listener. This art was essential to the evocative 6. Partite sopra l'Aria della Romanesca (1–14) 21’49 power of Frescobaldi’s music. In his performance Francesco Gesualdi establishes a particular spatial and temporal Carlo Gesualdo (1566–1613) universe in which the constraints of absolute formal rigour are reconciled with 7. Canzon francese del Principe 6’40 freedom of accentuation and vital breath, so as to invest each execution with the immediacy of originality. In this ability to renew with each rendering, Gesualdi’s Alessandro Solbiati (1956) playing speaks for the way wonderment can forge the essential relationship between 8. -

Max Reger's Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Carole Terry, Chair Jonathan Bernard Craig Sheppard Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Wyatt Smith ii University of Washington Abstract Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Carole Terry School of Music The history and performance of transcriptions of works by other composers is vast, largely stemming from the Romantic period and forward, though there are examples of such practices in earlier musical periods. In particular, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach found its way to prominence through composers’ pens during the Romantic era, often in the form of transcriptions for solo piano recitals. One major figure in this regard is the German Romantic composer and organist Max Reger. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Reger produced many adaptations of works by Bach, including organ works for solo piano and four-hand piano, and keyboard works for solo organ, of which there are fifteen primary adaptations for the organ. It is in these adaptations that Reger explored different ways in which to take these solo keyboard works and apply them idiomatically to the organ in varying degrees, ranging from simple transcriptions to heavily orchestrated arrangements. This dissertation will compare each of these adaptations to the original Bach work and analyze the changes made by Reger. It also seeks to fill a void in the literature on this subject, which often favors other areas of Reger’s transcription and arrangement output, primarily those for the piano. -

A Study of Selected Piano Toccatas in the Twentieth Century: a Performance Guide Seon Hwa Song

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Study of Selected Piano Toccatas in the Twentieth Century: A Performance Guide Seon Hwa Song Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A STUDY OF SELECTED PIANO TOCCATAS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By SEON HWA SONG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Seon Hwa Song defended on January 12, 2011. _________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo Professor Directing Treatise _________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative _________________________ Douglas Fisher Committee Member _________________________ Gregory Sauer Committee Member Approved: _________________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo, Professor and Coordinator of Keyboard Area _____________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Above all, I am eagerly grateful to God who let me meet precious people: great teachers, kind friends, and good mentors. With my immense admiration, I would like to express gratitude to my major professor Leonard Mastrogiacomo for his untiring encouragement and effort during my years of doctoral studies. His generosity and full support made me complete this degree. He has been a model of the ideal teacher who guides students with deep heart. Special thanks to my former teacher, Dr. Karyl Louwenaar for her inspiration and warm support. She led me in my first steps at Florida State University, and by sharing her faith in life has sustained my confidence in music. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Music for the Cimbalo Cromatico and the Split-Keyed Instruments in Seventeenth-Century Italy," Performance Practice Review: Vol

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 8 Number 1 Spring Music for the Cimbalo Cromatico and the Split- Keyed Instruments in Seventeenth-Century Italy Christopher Stembridge Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Stembridge, Christopher (1992) "Music for the Cimbalo Cromatico and the Split-Keyed Instruments in Seventeenth-Century Italy," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 1, Article 8. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199205.01.08 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Early Baroque Keyboard Instruments Music for the Cimbalo Cromatico and Other Split- Keyed Instruments in Seventeenth-Century Italy* Christopher Stembridge The Concept of the Cimbalo Cromatico Although no example of such an instrument is known to have survived intact, the cimbalo cromatico was a clearly defined type of harpsichord that apparently enjoyed a certain vogue in Italy during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.1 The earliest use of the term is found in the titles of two toccatas per il cimbalo cromatico included by Ascanio Mayone in his Secondo Libro di Diversi Capricci per Sonare published in Naples in 1609.2 Subsequently the term was used in publications by This is the first of three related articles. The second and third, to be published in subsequent issues of Performance Practice Review, will deal with the instruments themselves. -

Three Sonatas for Piano by Emma Lou Diemer Chin-Ming Michelle Lin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Three sonatas for piano by Emma Lou Diemer Chin-Ming Michelle Lin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lin, Chin-Ming Michelle, "Three sonatas for piano by Emma Lou Diemer" (2007). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1660. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1660 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THREE SONATAS FOR PIANO BY EMMA LOU DIEMER A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music by Chin-Ming Lin B.F.A., Tunghai University, Taiwan, 2000 M.M., Carnegie Mellon University, 2003 December, 2007 To my parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the members of my committee throughout my doctoral studies and during the writing of this paper at Louisiana State University. I am very thankful for my previous piano professor Dr. Jennifer Hayghe for her tremendous guidance and piano teaching in first two years of my doctoral residency; a special thanks to my major professor Mr. Gregory Sioles for his enthusiastic and brilliant teaching in piano and his dedication in revising this written document and helping me prepare for my lecture recital; Professor Michael Gurt for contributing his insightful expertise and musicianship; Dr. -

Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion

Requirements for Audition 1 Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion March 2019 The NZSO tunes at A440. Auditions must be unaccompanied. Solo 01 | BACH | LUTE SUITE IN E MINOR MVT. 6 – COMPLETE (NO REPEATS) 02 | DELÉCLUSE | ETUDE NO. 9 FROM DOUZE ETUDES - COMPLETE Excerpts BASS DRUM 7 03 | BRITTEN | YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO THE ORCHESTRA .................................. 7 04 | MAHLER | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 1 ......................................................................... 8 05 | PROKOFIEV | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 4 .................................................................... 9 06 | SHOSTAKOVICH | SYMPHONY NO. 11 MVT. 1 .........................................................10 07 | STRAVINSKY | RITE OF SPRING ...............................................................................10 08 | TCHAIKOVSKY | SYMPHONY NO. 4 MVT. 4 ..............................................................12 BASS DRUM WITH CYMBAL ATTACHMENT 13 09 | STRAVINSKY | PETRUSHKA (1947) ...........................................................................13 New Zealand Symphony Orchestra | Sub-Principal Percussion | March 2019 2 Requirements for Audition CYMBALS 14 10 | DVOŘÁK | SCHERZO CAPRICCIOSO ........................................................................14 11 | MUSSORGSKY | NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN .........................................................14 12 | RACHMANINOV | PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 MVT. 3 ................................................15 13 | SIBELIUS | FINLANDIA ................................................................................................15 -

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Toccata Seconda

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji’s Toccata Seconda Jeremy Chaulk 1 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Preludio-Toccata ................................................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Preludio-Corale .............................................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Scherzo .......................................................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Aria .............................................................................................................................................. 10 2.5 Ostinato ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.6 Notturno ...................................................................................................................................... 13 2.7 Interludio – Moto Perpetuo .......................................................................................................... 13 2.8 Cadenza: punta d’Organo ............................................................................................................ 16 2.9 Fuga libera a cinque voci .............................................................................................................. 17 -

MONTEVERDI's OPERA HEROES the Vocal Writing for Orpheus And

MONTEVERDI’S OPERA HEROES The Vocal Writing for Orpheus and Ulysses Gustavo Steiner Neves, M.M. Lecture Recital Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Karl Dent Chair of Committee Quinn Patrick Ankrum, D.M.A. John S. Hollins, D.M.A. Mark Sheridan, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2017 © 2017 Gustavo Steiner Neves Texas Tech University, Gustavo Steiner Neves, May 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES iv LIST OF TABLES iv CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1 Thesis Statement 3 Methodology 3 CHAPTER II: THE SECOND PRACTICE AND MONTEVERDI’S OPERAS 5 Mantua and La Favola d’Orfeo 7 Venice and Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria 13 Connections Between Monteverdi’s Genres 17 CHAPTER III: THE VOICES OF ORPHEUS AND ULYSSES 21 The Singers of the Early Seventeenth Century 21 Pitch Considerations 27 Monteverdi in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries 30 Historical Recordings and Performances 32 Voice Casting Considerations 35 CHAPTER IV: THE VOCAL WRITING FOR ORPHEUS AND ULYSSES 37 The Mistress of the Harmony 39 Tempo 45 Recitatives 47 Arias 50 Ornaments and Agility 51 Range and Tessitura 56 CHAPTER V: CONCLUSIONS 60 BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 ii Texas Tech University, Gustavo Steiner Neves, May 2017 ABSTRACT The operas of Monteverdi and his contemporaries helped shape music history. Of his three surviving operas, two of them have heroes assigned to the tenor voice in the title roles: L’Orfeo and Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria. -

Toccata for Orchestra"

About "Toccata for Orchestra" "Toccata for Orchestra" was commissioned by a consortium of orchestras including the Evansville Philharmonic Orchestra, Alfred Savia, Music Director; the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Mario Venzago, Music Director; the Oklahoma City Philharmonic, Joel Levine, Music Director; the Omaha Symphony, Thomas Wilkins, Music Director; and the Virginia Symphony Orchestra, JoAnn Falletta, Music Director. The Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra premiered the work in March of 2007. This lively work is meant to be a miniature concerto for orchestra. From the string quartet before letter P to the lyrical flute and clarinet solos in the middle of the work to the fugue section that begins at letter P, every instrument in the orchestra has a solo moment somewhere in this piece. "Toccata for Orchestra" opens quietly with a rhythmic, low register xylophone solo. This quintal harmony and rhythm sets the stage for the opening theme. A former student and now composition colleague, Kevin James, had mentioned to me his discussion of toccatas with the organist at the main cathedral in Siena, Italy. He was told that in the 17th century, toccatas were typically improvisational preludes for church services often involving music that would sequence keys in fourths or fifths to see which notes on the organ might be malfunctioning, as they were unpredictable instruments at the time. This practice would inform the organist of which notes to avoid in the rest of the service. I decided to incorporate this musical idea into my toccata. The melodic pattern of fifths states all of the notes in the chromatic scale by measure 6, and goes on to be the basis for the B theme first heard at letter D in this work. -

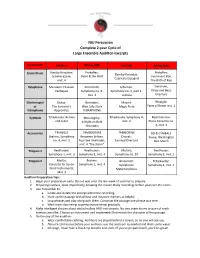

NIU Percussion Complete 2‐Year Cycle of Large Ensemble Audi On

NIU Percussion Complete 2‐year Cycle of Large Ensemble Audion Excerpts Instrument Fall Even Spring Odd Fall Odd Spring Even Rimsky‐Korsakov: Prokofiev: Prokofiev: Snare Drum Rimsky‐Korsakov: Scheherazade, Peter & the Wolf Lieutenant Kijé, Capriccio Espagnol mvt. 4 The Birth of Kijé Xylophone Messiaen: Oiseaux Persiche, Schuman: Gershwin, Exoques Symphony no. 6, Symphony no. 3, part 2, Porgy and Bess, mvt. 4 toccata Overture Glockenspiel Dukas: Bernstein, Mozart: Respighi: or The Sorcerer’s West Side Story Magic Flute Pines of Rome mvt. 1 Vibraphone Apprence VIBRAPHONE Cymbals Tchaikovsky: Romeo Mussorgsky: Tchaikovsky: Symphony 4, Rachmaninov: and Juliet A Night on Bald mvt. 4 Piano Concerto no. Mountain 2, mvt. 3 Accessories TRIANGLE TAMBOURINE TAMBORINE BD & CYMBALS Brahms, Symphony Benjamin Brien: Dvorak: Sousa, Washington no. 4, mvt. 3 Four Sea Interludes, Carnival Overture Post March mvt. 4 “the storm” Timpani 1 Beethoven: Beethoven: Mozart, Beethoven: Symphony 1, mvt. 3 Symphony 9, mvt. 4 Symphony no. 39 Symphony 9, mvt. 1 Timpani 2 Marn, Brahms: Hindemith: Tchaikovsky: Concerto for Seven Symphony 1, mvt. 4 Symphonic Symphony 4, mvt. 1 Wind Instruments, Metamorphosis Mvt. 3 Audion Preparaon Tips: 1. Begin your preparaon early. Do not wait unl the last week of summer to prepare. 2. Preparing involves, most importantly, knowing the music! Study recordings before you learn the notes. 3. Use Transcribe! to: a. locate and isolate the excerpt within the recording. b. mark up the passage with phrase and measure markers as helpful. c. loop phrases and play along with them. Construct the passage one phrase at a me. d. Work from slow tempi to performance tempi gradually. -

Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 50 in C Minor

Second PhD Presentation Topic: Intertextuality and Narrativity in Medtner’s Toccata: Piano Concerto No. 2, op. 50 in C minor (1880-1951) John Zachariah Diutlwileng Ntsepe Scholarly Doctoral Programme (PhD) University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz (KUG) Advisors: Prof. Christian Utz Prof. Peter Revers Prof. Christian Flamm 17 January 2020 SECOND PRESENTATION Introduction In my first presentation, I introduced the topic of my thesis: Investigating Nikolai Medtner’s Piano Concertos. Medtner’s sonatas and concertos form an imperative part of his oeuvre. The core of my dissertation is delineated to his three piano concertos. Medtner’s dual cultural heritage (Russian and German) is highlighted by influences from composers such as Beethoven, Chopin, Grieg, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Schubert, Schumann, Scriabin, Tchaikovsky and Wagner, including poets such as Fet, Geothe, Heine, Lermantov, Nietzeche, Pushkin and Tyutchev. Christoph Flamm (1995: 69) also stresses Medtner’s mutually beneficial friendship with the Symbolist poet and theorist, Andrei Bely. Even though Medtner was mostly auto-didactical, shortly after his graduation (around the beginning of 1901) Medtner had consultations and discussions regarding form and structural problems with Sergej Taneev (Flamm 1995:5). However, Medtner’s natural talent provided him with original and individual strategies for overcoming formal and structural conundrums in his concertos. Moreover, due to their multiple illusions and references to other musical and literary works, Medtner’s concertos require