Tourism Facing a Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALLEGATO 4: CARTOGRAFIA DI INQUADRAMENTO (Fonte: Sistema Informativo Territoriale – SITER - Della Provincia Di Bergamo)

ALLEGATO 4: CARTOGRAFIA DI INQUADRAMENTO (fonte: Sistema Informativo TERritoriale – SITER - della Provincia di Bergamo) VILMINORE DI SCALVE VALGOGLIO GROMO COLERE ´ OLTRESSENDA ALTA ARDESIO ANGOLO TERME CASTIONE DELLA PRESOLANA FINO DEL MONTE VILLA D`OGNA PARRE PIARIO ONORE CLUSONE ROGNO SONGAVAZZO CERETE ROVETTA COSTA VOLPINO BOSSICO SOVERE GANDINO LOVERE 1:50.000 Confine comunale Industriale Raffreddamento Scarico di emergenza privato Scarico depurato pubblico Terminale pubblica fognatura bianche Scarico di emergenza (Staz. sol. / bypass) Sfioratore Sfioratore/scarico staz. sollevamento Reticolo idrografico Carta degli scarichi autorizzati in corpo d'acqua superficiale VILMINORE DI SCALVE VALGOGLIO GROMO COLERE ´ OLTRESSENDA ALTA ARDESIO ANGOLO TERME CASTIONE DELLA PRESOLANA FINO DEL MONTE VILLA D`OGNA PARRE PIARIO ONORE CLUSONE ROGNO SONGAVAZZO CERETE ROVETTA COSTA VOLPINO BOSSICO SOVERE GANDINO LOVERE 1:50.000 Confine comunale Sorgenti / Fontanili Derivazioni superficiali Pozzi Potabile Potabile Potabile Antincendio Antincendio Antincendio Igienico Igienico Igienico Industriale Industriale Industriale Produzione Energia Produzione Energia Produzione Energia Piscicoltura Piscicoltura Piscicoltura Zootecnico Zootecnico Irriguo Zootecnico Irriguo Uso Domestico Irriguo Uso Domestico Altro uso Uso Domestico Altro uso Altro uso Carta delle piccole derivazioni di acqua VILMINORE DI SCALVE VALGOGLIO GROMO COLERE ´ OLTRESSENDA ALTA ARDESIO ANGOLO TERME CASTIONE DELLA PRESOLANA FINO DEL MONTE VILLA D`OGNA PARRE PIARIO ONORE CLUSONE ROGNO SONGAVAZZO -

Bossico Dintorni

Bossico Dintorni Localita vicine a Bossico A Cerete D Songavazzo Lago d'Iseo: laghi vicino a Bossico Il lago d'Iseo si trova in Lombardia ed è lungo 25 Km, largo 4,7 Km con una profondità massima di 251 metri. Si tratta di un lago di origine glaciale, il grande ghiacciaio dell'Oglio ha lasciato, ancora oggi, i segni della sua presenza rappresentati da grigi massi di arenaria sparsi sul territorio. E'lo stesso fiume Oglio che funge da immissario ed emissario del lago. Nella parte centrale del lago troviamo l'isola di Siviano, detta comunemente Monte Isola, la più vasta tra le isole lacuali della penisola e gli isolotti di Loreto e San Paolo. Il fascino dell'ambiente lacustre, la prealpe operosa, i meravigliosi paesaggi e la pittura (troviamo molte opere venete nella galleria di Lovere), numerosi sono i motivi d'interesse di questo itinerario. Il lago venne dichiarato "il più industriale" d'Italia: la Valcamonica, solcata dal fiume Oglio, è un mondo prealpino ricoperto da vigneti e castagni che scendono dolcemente sui coltivi del fondovalle; le località intorno alla gola del Dezzo offrivano grandi quantità di ferro che diedero avvio all'industrializzazione della zona. Un lago dunque, che al fascino dell'ambiente unisce interessanti centri e località turistiche e industriali famose in tutta la penisola, un itinerario da non perdere. Come arrivare: Autostrada A4: da Milano direzione Venezia uscita Palazzolo Autostrada A4: da Verona direzione Milano uscita Rovato o Palazzolo Località posizionate sulla mappa B Costa Volpino C Lovere E Sovere -

[email protected] COMUNE DI

Regione Lombardia - Giunta DIREZIONE GENERALE INFRASTRUTTURE, TRASPORTI E MOBILITA' SOSTENIBILE INFRASTRUTTURE VIARIE E AEROPORTUALI VIABILITA' E MOBILITA' CICLISTICA Piazza Città di Lombardia n.1 www.regione.lombardia.it 20124 Milano [email protected] Tel 02 6765.1 Protocollo S1.2019.0010104 del 20/03/2019 PROVINCIA DI BERGAMO Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ADRARA SAN MARTINO Email: [email protected] mbardia.it COMUNE DI ADRARA SAN ROCCO Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ALBANO SANT'ALESSANDRO Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ALBINO Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ALGUA Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ALME Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ALMENNO SAN BARTOLOMEO Email: [email protected] mo.it COMUNE DI ALMENNO SAN SALVATORE Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ALZANO LOMBARDO Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI AMBIVERE Email: [email protected] Referente per l'istruttoria della pratica: PAOLA VIGO Tel. 02/6765.5137 GABRIELE CASILLO Tel. 02/6765.8377 COMUNE DI ANTEGNATE Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ARCENE Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ARDESIO Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI ARZAGO D'ADDA Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI AVERARA Email: [email protected] COMUNE DI AVIATICO Email: [email protected] -

20130508 Regedil 1Intestazione

COMUNE DI TREVIOLO Provincia di Bergamo REGOLAMENTO EDILIZIO COMUNALE lavori preparatori della Commissione Comunale Urbanistica verbale n. 2 in seduta del 15/3/2010 esame e confronto istruttorio ASL in seduta del 22/3/2010 parere ASL BG acquisito con lettera prot.n. U0083794/m.7.50 in data 22/6/2010 parere della Commissione Comunale Urbanistica verbale n. 8 in seduta del 10/11/2010 approvato con deliberazione consiliare n. 15 in data 27/4/2011 Revisione 01 adottata dal Consiglio Comunale n. 70 in data 30/11/2012 parere ASL BG - DDG n. 79 in data 25/1/2013 approvata dal Consiglio Comunale con deliberazione n. 8 del 8/5/2013 REVISIONE 1 maggio 2013 coordinamento generale geom. Alberto Dalleo Responsabile di Settore dell’Area 3 Tecnico-Progettuale elaborazione e ricerca geom. Rosalia Cuomo Responsabile Servizio Ecologia - Area 3 Tecnico-Progettuale coordinamento istituzionale Gianfranco Masper Sindaco con competenza sull’Urbanistica e l’Edilizia Privata PAGINA BIANCA SOMMARIO DEGLI ARTICOLI CAPO I - NORME GENERALI Titolo I – Disposizioni generali Art. 1 - Contenuto del Regolamento Edilizio................................................................................. Pag. 1 Art. 2 - Deroga alle norme del Regolamento Edilizio ................................................................... Pag. 1 Art. 3 - Soggetti legittimati a svolgere attività edilizia ................................................................... Pag. 1 CAPO II - GLI INTERVENTI DI TRASFORMAZIONE DEL TERRITORIO TITOLO I – Provvedimenti abilitativi ai lavori Art. -

Songavazzo - Falecchio - Bossico - Lovere

Traversata: Songavazzo - Falecchio - Bossico - Lovere Traversata Songavazzo - Bossico - Lovere Da Songavazzo m.640 si sale alla località Falecchio, si segue la stradina fin dopo le cascine di Camasù. Si devia su sentiero a destra, (indicazione Sorgente Cremonella e Bossico ), Indi con percorso ondulato alla Chiesetta dei Caduti m.1029 e in discesa a Bossico In caso di necessità m.860. Dislivelli totali: + m.450 - m. 220 in ore 3 circa. Comunicare al: Rientro a Lovere m. 200 dis - m. 450 in ore 1.30 N. 346 42 33 397 Coordinatori: Cremonesi Linda - Frigeni Franco Da Songavazzo (m. 640) a Bossico (m. 860) e a Lovere lago (m. 200) A Songavazzo occorre portarsi al cimitero dove la strada curva per salire a Falecchio e percorrendo scorciatoie e strada raggiungeremo l'altopiano, balcone verso la vai Borlezza e la Presolana. (All'altopiano è possibile arrivare anche in macchina). Dal piazzale dove sostano le auto, la stradina prosegue nella pineta, arrivati a un bivio si continua a destra costeggiando la valle, ammantata d'abeti e larici, in direzione Sud-Est. A sinistra la roccia del sovrastante monte Pizzo (m. 1190), che ogni tanto affiora è formata da stratificazioni oblique di calcare del Retico. A destra oltre la valle si trova la località Camnù alto e poco più avanti Camnù basso. Dopo circa un Km. da Falecchio si attraversa l'alveo asciutto del Tribes e si prosegue sulla sinistra idrografica, trovando sulla mulattiera dei begli agglomerati morenici. Dopo dieci minuti si arriva ai prati di Camasù a m.1062 dove si trovano delle cascine. -

BOSSICO: La Scaramozzino BOSSICO: » a Pag

www.araberara.it dal 1987 [email protected] dal 1987 VAL SERIANA, VAL DI SCALVE, ALTO E BASSO SEBINO, VAL CALEPIO, LAGO D’ENDINE, VAL CAVALLINA, BERGAMO Autorizzazione Tribunale di Bergamo: 6ZNSINHNSFQJ Pubblicità «Araberara» Numero 8 del 3 aprile 1987 Tel. 0346/28114 Fax 0346/921252 Redazione Via S. Lucio, 37/24 - 24023 Clusone 30 Agosto 2013 Composizione: Araberara - Clusone Tel. 0346/25949 Fax 0346/27930 “Poste italiane Spa - Spedizione in A.P. - D.L. 353/2003 Anno XXVII - n. 16 (443) - E 1,80 Stampa: C.P.Z. Costa di Mezzate (Bg) (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art.1, comma 1, DCB Bergamo” Direttore responsabile: Piero Bonicelli CODICE ISSN 1723 - 1884 RICOMINCIO SCUOLA DAL CIELO 'JSJIJYYFLJSYJ (p.b.) “Il ladro di cavalli non era lui, ma fu im- E DAL VENTO piccato per comodità” (Vecchioni). C’è tutto un » IL PICCO A CHIUDUNO flone cinematografco (americano) sui facili lin- Gli editoriali ARISTEA CANINI ciaggi con folle inferocite che vogliono “farsi giu- stizia”, la creazione mediatica di “mostri” di como- Gli stipendi do, condanne a morte revocate all’ultimo istante, Ricomincio da un sasso che La folla ateniese aveva il potere di mandare in rotola piano lungo il selciato esilio per dieci anni quelli che diventavano trop- mentre mi rimetto in cammino po potenti (con l’ostracismo, nome derivato dalle dei “Dirigenti verso il mio inizio d’anno, che tavolette di coccio su cui scrivevano il nome del poi settembre è così per tutti, il futuro esiliato). E comunque Socrate viene con- vero inizio, che ogni inizio ha dannato a morte da un’assemblea popolare che scolastici” dentro qualcosa di magico e se lo nella storia (raccontata da Platone) resta come conserva gelosamente, perché il un eclatante esempio di ottusità. -

CERATELLO ATTRAVERSO I SECOLI La Vicenda Storica Di Ceratello Si

CERATELLO ATTRAVERSO I SECOLI La vicenda storica di Ceratello si perde nella notte del tempo e si identifica con quella dei paesi relativamente più grossi del fondo valle Camonica e dell’Alto Sebino, Volpino, Rogno e Lovere. La Costa di Volpino fu luogo di abitazione di popolazioni celtiche, che erano popolazioni precedenti al dominio romano, insediatesi dall’età del ferro, in ondate migratorie susseguenti, fino al tardo medioevo. Proprio nel linguaggio e in abbondanti ritrovamenti tombali e nella toponomastica locale possiamo tentare di fare alcune ipotesi, atte a togliere il velo, sul mistero dei primi abitatori di Ceratello. [Vedi appendice 1] COLLOCAZIONE STRATEGICA Discendenti dai Camuni, popolazione indigena della Valle Camonica, i nostri antenati, risalirono i pendii della Costa in cerca di nuovi pascoli e luoghi più sicuri dal continuo passare di popoli e di inondazioni distruttive. Su questo balcone naturale lasciato dallo scavo del ghiacciaio che aveva formato la Valle Camonica e il Sebino, (vedi Una Gemma Subalpina di Alessio Amighetti celebre geologo nato a Ceratello) i pastori del passato avevano trovato un terreno sufficientemente adatto per sopravvivere, contendendo i pascoli alla folta vegetazione. La invidiabile posizione strategica che consentiva una visione di tutta la bassa valle da nord est a sud ovest, consigliava i potenti signori della pianura a mantenere, su questo monte, un castellano che aveva il compito di segnalare ogni spiacevole arrivo di nemici e consentire una adeguata difesa. Disboscando le zone più protette e pianeggianti, costruendo muri a secco per strappare un po’ di terra coltivabile alle rocce sporgenti, gli antichi abitatori si insediarono stabilmente su uno dei tre terrazzi che compongono gli altipiani e che caratterizzano tutto il costone della montagna dalla Valle di Supine alla Val Borlezza. -

Comuni Aderenti: Comuni in Corso Di Adesione

Comuni aderenti: Albano Sant'Alessandro – Albino – Almè - Almenno San Bartolomeo - Almenno San Salvatore - Alzano Lombardo – Ambivere – Comuni in corso di Arcene – Ardesio - Arzago d'Adda – Averara - adesione: Azzano San Paolo – Azzone – Barbata – Cenate Sopra – Clusone Bariano – Barzana – Berbenno – Bergamo – Entratico - Songavazzo Bianzano – Blello - Bolgare – Boltiere - – Vilminore di Scalve Bonate Sopra - Bonate Sotto – Bossico – Bottanuco – Bracca – Brembate - Brembate di Sopra – Brembilla - Brignano Gera d'Adda – Brusaporto – Calcinate – Calcio – Caluisco d’Adda - Calvenzano - Canonica d'Adda - Capriate San Gervasio – Caprino Bergamasco – Caravaggio - Carobbio degli Angeli – Comuni non Carvico – Casazza - Casirate d'Adda – aderenti: Casnigo - Castelli Calepio - Castione della Adrara San Martino - Presolana – Castro – Cavernago - Cenate Adrara San Rocco – Sotto - Cene – Cerete - Chignolo d'Isola – Algua – Antegnate – Chiuduno - Cisano Bergamasco – Ciserano - Aviatico - Bagnatica – Cividate al Piano – Colere - Cologno al Serio Bedulita - Berzo San – Colzate - Comun Nuovo - Corna Imagna – Fermo – Borgo di Terzo Cortenuova - Costa Volpino – Covo – Curno – – Branzi – Brumano - Cusio – Dalmine – Endine Gaiano - Fara Gera Camerata Cornello – d'Adda - Fara Olivana con Sola – Filago - Fino Capizzone - Carona - del Monte - Fiorano al Serio – Fontanella – Cassiglio - Castel Fonteno – Foppolo - Foresto Sparso – Rozzone - Cazzano Gandellino – Gandino - Gaverina Terme – Sant'Andrea – Cornalba Gorlago – Gorle - Gorno – Grassobbio – - Costa di -

Legambiente, Bandiera Verde in Val Brembana. Nera Per Bossico E Rovetta Written by Redazione | 5 Agosto 2015

Legambiente, bandiera verde in Val Brembana. Nera per Bossico e Rovetta written by Redazione | 5 Agosto 2015 Sulle montagne lombarde, l’unica bandiera verde per il 2015 sventola per il polo culturale Mercatorum e Priula – “Vie di Migranti, Artisti, dei Tasso e di Arlecchino”, mentre le bandiere nere sono ben tre: ai Comuni di Bossico e Rovetta (Bg), al Comune di Valvestino (Bs) e una condivisa tra Lombardia e Trentino e Alto Adige/ Südtirol per la proposta di scissione e declassamento del Parco dello Stelvio. Sono questi i vessilli che oggi Legambiente ha consegnato in occasione della partenza della Carovana delle Alpi, la campagna annuale sullo stato di salute dell’arco alpino, che anche quest’anno torna a segnalare le situazioni più virtuose, assegnando le Bandiere Verdi, e le realtà peggiori, quelle che mettono in campo le scelte più impattanti, che aumentano il consumo di suolo, che incidono pesantemente sulla qualità ambientale e sociale della vita in montagna, e che si fregiano quindi delle Bandiere Nere. «Il dossier di Carovana delle Alpi 2015 mostra un panorama a luci ed ombre. Certamente continuare a investire in nuove colate di cemento e in altre grandi infrastrutture stradali per aumentare l’attrattività turistica corrisponde ad una ipotesi di sviluppo obsoleta, anzi decisamente sorpassata – ha dichiarato il presidente nazionale di Legambiente Vittorio Cogliati Dezza – Non è sfregiando ulteriormente il territorio che potremo rispondere alla attuale crisi economica, bensì con una visione più ampia e lungimirante dello sviluppo imprenditoriale montano, con una strategia basata sulla valorizzazione della natura e sul protagonismo delle comunità locali, capaci di creare connessioni tra arte, cultura, tradizioni, ambiente ed enogastronomia. -

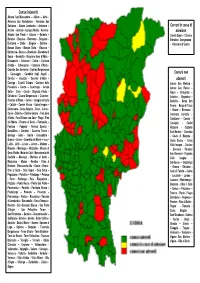

L'andamento Dei Contagi

Incremento Incremento Incremento Incremento Incremento Incremento L’andamento dei contagi ultimi 7 giorni per mille ab. ultimi 7 giorni per mille ab. ultimi 7 giorni per mille ab. I DATI NELL’ULTIMA Cassiglio 0 0,0 Lallio 1 0,2 Rota d'Imagna 0 0,0 SETTIMANA Castel Rozzone 0 0,0 Leffe 1 0,2 Rovetta 2 0,5 Castelli Calepio 9 0,8 Lenna 0 0,0 San Giovanni Bianco 3 0,6 Castione della Presolana 1 0,3 Levate 3 0,8 San Paolo d'Argon 2 0,3 Incidenza x 1.000 abitanti Castro 0 0,0 Locatello 0 0,0 San Pellegrino Terme 0 0,0 Cavernago 2 0,7 Lovere 2 0,4 Santa Brigida 0 0,0 1,68 - 4,96 Cazzano Sant'Andrea 0 0,0 Lurano 1 0,3 Sant'Omobono Terme 0 0,0 1,01 - 1,68 Cenate Sopra 1 0,4 Luzzana 0 0,0 Sarnico 5 0,7 0,69 - 1,01 Cenate Sotto 0 0,0 Madone 2 0,5 Scanzorosciate 3 0,3 Cene 1 0,2 Mapello 3 0,4 Schilpario 0 0,0 0,45 - 0,69 Cerete 0 0,0 Martinengo 5 0,5 Sedrina 0 0,0 0,08 - 0,45 Chignolo d'Isola 1 0,3 Medolago 0 0,0 Selvino 0 0,0 Chiuduno 3 0,5 Mezzoldo 0 0,0 Seriate 5 0,2 Cisano Bergamasco 1 0,2 Misano di Gera d'Adda 1 0,3 Serina 0 0,0 Settimana Ciserano 2 0,3 Moio de' Calvi 0 0,0 Solto Collina 0 0,0 20-26 gennaio 2021 Cividate al Piano 1 0,2 Monasterolo del Castello 0 0,0 Solza 0 0,0 Clusone 3 0,3 Montello 1 0,3 Songavazzo 0 0,0 Colere 0 0,0 Morengo 0 0,0 Sorisole 1 0,1 Cologno al Serio 6 0,5 Mornico al Serio 3 1,0 Sotto il Monte Giovanni XXIII 3 0,7 Comuni che hanno fatto Colzate 0 0,0 Mozzanica 7 1,6 Sovere 9 1,7 registrare zero positivi Comun Nuovo 5 1,1 Mozzo 0 0,0 Spinone al Lago 1 1,0 nella settimana Corna Imagna 0 0,0 Nembro 1 0,1 Spirano 1 0,2 20-26 gennaio 2021 Cornalba 0 0,0 Olmo al Brembo 0 0,0 Stezzano 9 0,6 Cortenuova 5 2,8 Oltre il Colle 0 0,0 Strozza 0 0,0 Costa di Mezzate 0 0,0 Oltressenda Alta 0 0,0 Suisio 0 0,0 Costa Serina 0 0,0 Oneta 0 0,0 Taleggio 0 0,0 Costa Valle Imagna 0 0,0 Onore 0 0,0 Tavernola Bergamasca 0 0,0 Costa Volpino 8 0,9 Orio al Serio 2 1,1 Telgate 6 1,1 Covo 0 0,0 Ornica 0 0,0 Terno d'Isola 2 0,2 Incremento Incremento Incremento Incremento Credaro 1 0,3 Osio Sopra 1 0,2 Torre Boldone 5 0,6 ultimi 7 giorni per mille ab. -

Allegato a DGR 4733

Direzione Generale Istruzione, Formazione e Lavoro ALLEGATO A alla DGR n. X/4733 del 22 gennaio 2016 PIANO DI ORGANIZZAZIONE DELLA RETE DELLE ISTITUZIONI SCOLASTICHE PER L'A.S. 2016-2017 Prov. Sede Aut. Cod. Aut. Cod. Sede Denominazione Nr. Sedi Ciclo Tipo autonomia Tipo sede Alunni Comune Indirizzo Montano BG Sede BGIC804004 IC di Vilminore di Scalve 8 Omnicomprensivo Omnicomprensivo 329 VILMINORE DI SCALVE Via Locatelli, 8/A BG BGIC804004 BGAA804011 Infanzia - Pezzolo Scuola dell'Infanzia Ordinaria VILMINORE DI SCALVE Via Bianchi, s.n.c. SI BG BGIC804004 BGAA804022 Infanzia - Schilpario Scuola dell'Infanzia Ordinaria SCHILPARIO Via della Costa, s.n.c. SI BG BGIC804004 BGEE804027 Primaria - Colere Scuola Primaria Ordinaria COLERE Piazza Risorgimento, 1 SI BG BGIC804004 BGEE804038 Primaria - Schilpario Scuola Primaria Ordinaria SCHILPARIO Via Nazionale, 1 SI BG BGIC804004 BGEE804049 Primaria - Vilminore di Scalve Scuola Primaria Ordinaria VILMINORE DI SCALVE Via Locatelli, 8/a SI BG BGIC804004 BGMM804026 Secondaria Primo Grado - Vilminore di Scalve Scuola Secondaria I grado Ordinaria VILMINORE DI SCALVE Via Locatelli, 8/a SI BG BGIC804004 BGMM804037 Secondaria Primo Grado - Cardinale Maj Scuola Secondaria I grado Ordinaria SCHILPARIO Via Nazionale, s.n.c. SI BG BGIC804004 BGTD150004 I.T. Tecnologico ed Economico - Vilminore Scuola Secondaria II grado Istituto Tecnico Ordinaria VILMINORE DI SCALVE Via Vittorio Emanuele II, 11 SI BG Sede BGIC80500X IC di Tavernola Bergamasca 9 Primo ciclo Comprensivo 611 TAVERNOLA BERGAMASCA Via Roma, 47 BG BGIC80500X BGAA80501R Infanzia - Tavernola Bergamaca Scuola dell'Infanzia Ordinaria TAVERNOLA BERGAMASCA Via Roma, 45 SI BG BGIC80500X BGAA80502T Infanzia - Riva di Solto Scuola dell'Infanzia Ordinaria RIVA DI SOLTO Via Torre, 2 SI BG BGIC80500X BGAA80503V Infanzia - Solto Collina Scuola dell'Infanzia Ordinaria SOLTO COLLINA Via Pozzi, 13 SI BG BGIC80500X BGEE805023 Primaria - Predore Scuola Primaria Ordinaria PREDORE Via Giovanni XXIII, s.n.c. -

Lovere - Sovere - Bossico // Lovere - Ceratello // Lovere - Castelfranco

ORARIO IN VIGORE dal 13 SETTEMBRE 2021 al 12 GIUGNO 2022 Linea L edizione 13 Settembre 2021 Contact center 035 289000 - Numero verde 800 139392 (solo da rete fissa) ANDATA www.bergamotrasporti.it | www.bergamo.arriva.it | www.sav-visinoni.it LOVERE - SOVERE - BOSSICO // LOVERE - CERATELLO // LOVERE - CASTELFRANCO Stagionalità corsa SCO SCO SCO SCO FER FER SCO FER SCO SCO SCO VSCO VSCO FER SCO FER SCO FER FER FER FER SCO FER FER SCO VSCO SCO SCO FER FER Giorni di effettuazione 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 6 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 12345 123456 12345 12345 123456 123456 NOTE A A E E C B B BOSSICO - piazza Chiesa 6:40 7:20 8:50 12:35 13:25 14:25 15:15 16:35 BIVIO PER BOSSICO 6:55 7:35 9:05 12:50 13:40 14:40 15:30 16:50 SOVERE - Municipio 7:00 7:00 7:40 8:25 9:10 9:10 12:25 12:55 12:55 13:45 13:55 14:25 14:45 14:55 15:25 15:40 16:55 SOVERE - Monumento 6:31 7:01 7:41 8:26 9:11 9:11 12:26 12:56 12:56 13:46 13:56 14:26 14:46 14:56 15:26 15:41 16:56 SOVERE - trattoria Pergola 6:35 7:05 7:45 8:30 9:15 12:30 13:00 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 15:45 17:00 PIANICO - Pensilina 6:38 7:08 7:48 8:33 9:18 12:33 13:03 14:03 14:33 15:03 15:33 15:48 17:03 CASTRO - loc.