Order Granting Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 an Analysis About Slang Language in The

p-ISSN: 2622-7843 e-ISSN: 2622-7894 Volume 3, Issue 01, 2020 AN ANALYSIS ABOUT SLANG LANGUAGE IN THE SONG LYRICS OF THE BLACK EYED PEAS (BOOM BOOM POW, IMMA BE, PUMP IT, SHUT UP, AND MY HUMPS Febryan Bayu Ramadhan1 English and Letters Faculty, Surakarta University [email protected], Arini Hidayah2 English and Letters Faculty, Surakarta University Abstract This research concerns the analysis of slang in the song lyrics of The Black Eyed Peas entitled Boom Boom Pow, Imma Be, Pump It, Shut Up, My Humps. The are two objectives in this research, namely to tell types of the slang appeared in this song, and to explain the meaning of slang. This analysis use descriptive method due to the fact that this research describe the meaning of the slangs. The data were taken from the song lyrics of The Black Eyed Peas entitled Boom Boom Pow, Imma Be, Pump It, Shut Up and My Humps. The researcher uses document and records method to gather the data which is by taking note of the slangs appeared in this song, then classifying them by their types, after that explaining their meaning, the researcher analyzing the meanings of the slang using an American Slang Dictionary and the researcher also asked the help of a Native American in analyzing the meanings of slang, finally, give a conclusion. The researcher found there are 37 total data of slangs in the song lyrics of The Black Eyed Peas entitled Boom Boom Pow, Imma Be, Pump It, Shut Up and My Humps. Then there are 37 total data of the meaning of slangs in the song lyrics of The Black Eyed Peas entitled Boom Boom Pow, Imma Be, Pump It, Shut Up and My Humps. -

Uptownlive.Song List Copy.Pages

Uptown Live Sample - Song List Top 40/ Pop 24k Gold - Bruno Mars Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Aint My Fault - Zara Larsson All of Me (John Legend) Another You - Armin Van Buren Bad Romance -Lady Gaga Better Together -Jack Johnson Blame - Calvin Harris Blurred Lines -Robin Thicke Body Moves - DNCE Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Cake By The Ocean - DNCE California Girls - Katy Perry Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Can’t Feel My Face - The Weeknd Can’t Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia Cheerleader - OMI Clarity - Zedd feat. Foxes Closer - Chainsmokers Closer – Ne-Yo Cold Water - Major Lazer feat. Beiber Crazy - Cee Lo Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Despacito - Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Beiber DJ Got Us Falling In Love Again - Usher Don’t Know Why - Norah Jones Don’t Let Me Down - Chainsmokers Don’t Wanna Know - Maroon 5 Don’t You Worry Child - Sweedish House Mafia Dynamite - Taio Cruz Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga ET - Katy Perry Everything - Michael Bublé Feel So Close - Calvin Harris Firework - Katy Perry Forget You - Cee Lo FUN- Pitbull/Chris Brown Get Lucky - Daft Punk Girlfriend – Justin Bieber Grow Old With You - Adam Sandler Happy – Pharrel Hey Soul Sister – Train Hideaway - Kiesza Home - Michael Bublé Hot In Here- Nelly Hot n Cold - Katy Perry How Deep Is Your Love - Calvin Harris I Feel It Coming - The Weeknd I Gotta Feelin’ - Black Eyed Peas I Kissed A Girl - Katy Perry I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift I Want You To Know - Zedd feat. Selena Gomez I’ll Be - Edwin McCain I’m Yours - Jason Mraz In The Name of Love - Martin Garrix Into You - Ariana Grande It Aint Me - Kygo and Selena Gomez Jealous - Nick Jonas Just Dance - Lady Gaga Kids - OneRepublic Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Lean On - Major Lazer feat. -

The Black Eyed Peas 'Pump It' up on Big Screens

THE BLACK EYED PEAS ‘PUMP IT’ UP ON BIG SCREENS NATIONWIDE WITH THE E.N.D. WORLD TOUR LIVE PRESENTED BY BLACKBERRY CONCERT EVENT LIVE FROM LOS ANGELES ON MARCH 30 NCM Fathom and AEG Live Team Up Again to Present an Exclusive One-Night Concert Performance with Behind-the-Scenes Footage Broadcast LIVE to Nearly 500 Select Movie Theaters Centennial, Colo. – Feb. 11, 2010 – The Black Eyed Peas are getting the party started across the country on The E.N.D. World Tour, presented by BlackBerry® and will rock the big screen as their concert performance from Los Angeles is transmitted LIVE nationwide on Tuesday, March 30th. Broadcast from STAPLES Center to nearly 500 select movie theaters across America, The Black Eyed Peas: The E.N.D. World Tour LIVE Presented by BlackBerry event will feature a 30-minute exclusive program for movie theater audiences, including behind-the-scenes footage and band interviews. Tickets for The Black Eyed Peas: The E.N.D. World Tour LIVE Presented by BlackBerry on March 30 at 10:30 p.m. Eastern / 9:30 p.m. Central / 8:30 p.m. Mountain / 7:30 p.m. Pacific are available at participating theater box offices and online at www.FathomEvents.com. For a complete list of theater locations and prices, please visit the web site (theaters and participants may be subject to change). “This tour is not the E.N.D. but the beginning of The Black Eyed Peas experience presented to you in full Pea fashion,” says Taboo of The Black Eyed Peas. -

Nova's Red Room with the Black Eyed Peas – Grand

NOVA’S RED ROOM WITH THE BLACK EYED PEAS – GRAND FINAL EVE Friday 14 September 2018 The Black Eyed Peas, one of the most commercially successful pop groups, will perform in a special Nova’s Red Room on Friday 28 September in Melbourne. Comprised of will.i.am, apl.de.ap and Taboo, the Black Eyed Peas are multi-platinum artists who have released six studio albums, selling over 30 million records worldwide. The group have won seven Grammy awards and have just announced their new album Masters of The Sun, set for release on 12 October, which coincides with the launch of their new single "Big Love". Having formed in LA in the late 80s, the Black Eyed Peas 2003’s breakthrough album, Elephunk, produced their first hit singles, “Where Is the Love,” “Shut Up,” “Hey Mama” and “Let’s Get It Started”. Monkey Business followed in 2005, producing the hit singles, “Don’t Phunk with My Heart,” “My Humps” and “Pump It,” and went triple-platinum around the world. The E.N.D. (The Energy Never Dies), their fifth studio album, and was nominated for six Grammy Awards, winning Best Pop Vocal Album and featuring the hit singles, “Boom Boom Pow” and the David Guetta- produced “I Gotta Feeling”. The E.N.D. sold more than 14.5 million copies worldwide and was nominated for six Grammy Awards, winning Best Pop Vocal Album. The Beginning, the band’s sixth studio album, featured the singles “The Time (Dirty Bit),” “Just Can’t Get Enough” and “Don’t Stop The Party” and was followed with a six month “The Beginning Massive Stadium Tour.” Masters of The Sun is the group's first studio album in eight years, following their multi-million selling 2010 LP The Beginning. -

L2 Digital Singles Pie Chart

Name ________________ Date _________ The top 10 best-selling digital singles in the world … ever! Sales Ranking Artist Single Released (millions) 1 The Black Eyed Peas "I Gotta Feeling" 2009 15 2 Adele ”Rolling in the Deep” 2010 14 3 The Black Eyed Peas ”Boom Boom Pow” 2009 11 4 Bruno Mars "Just the Way You Are" 2010 13 5 Bruno Mars "Grenade" 2010 10 6 Carly Rae Jepsen "Call Me Maybe" 2011 14 7 Eminem featuring Rihanna ”Love the Way You Lie” 2010 13 8 Flo Rida featuring T-Pain "Low" 2007 12 9 Gotye featuring Kimbra "Somebody That I Used to Know" 2011 13 10 Jason Mraz "I'm Yours" 2008 12 TASK: Make a pie chart to show the ‘Top 7’ digital single sales of all-time 1. Work out your total number of sales for the 7 singles and write in the total in the table 2. Show here your calculation for how many ‘degrees per part’. ___________________________________________________________ 3. Multiply the ‘part’ by each single’s number of sales and write it in the ‘angle’ column 4. Check your angles add up to 360 degrees Single Sales (millions) Angle (º) “I Gotta Feeling” ”Rolling in the Deep” ”Boom Boom Pow” "Just the Way You Are" "Grenade" "Call Me Maybe" ”Love the Way You Lie” Total Feb 2014. Kindly contributed by Martyn Staines, Newbury, Berkshire who adapted it from a resource from Janet Wilkins (Skillsworkshop, 2008). Page 1 of 2 Search for Martyn and Janet on www.skillsworkshop.org Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_best‐selling_singles#Best‐selling_digital_singles L2 Functional Maths / Adult Numeracy. -

New Songs Are Added to the List Every Week and This Is Just a Partial Song List

New songs are added to the list every week and this is just a partial song list The band will learn special songs if they don’t know them already (First dance Father daughter etc..) Classic 70s and 80s Dance and Disco P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing) ‐ Michael Jackson September ‐ Earth Wind and Fire Boogie Shoes ‐ K.C. & The Sunshine Band Got To Be Real ‐ Cheryl Lynn Don't Leave Me This Way ‐ Thelma Houston Play That Funky Music ‐ Wild Cherry Let's Groove Tonight ‐ Earth Wind & Fire Shake Your Body ‐ Jackson 5 Brick House ‐ The Commodores Get Down On It ‐ Kool & the Gang Don't Stop Til You Get Enough ‐ Michael Jackson I Will Survive ‐ Gloria Gaynor Bad Mamma Jamma – Carl Carlton Ladies' Night ‐ Kool & The Gang Singasong ‐ Earth Wind and Fire Lady Marmelade – Various Artists Working Day & Night ‐ Michael Jackson We Are Family ‐ Sister Sledge Rock With You – Michael Jackson Celebration ‐ Kool & the Gang Can't Get Enough Of Your Love ‐ Barry White Boogie Oogie Oogie – Taste of Honey Best of My Love ‐ The Emotions Glamorous Life ‐ Sheila E. You Dropped a Bomb On Me – The Gap Band Word Up – Cameo The Bird ‐ The Time Bad Girls ‐ Donna Summer Shake Your Groove Thing ‐ Peaches & Herb Shake Your Booty ‐ K.C. & the Sunshine Band Kiss – Prince Who’s That Lady – The Isley Brothers You’re My First, My Last, My Everything – Barry White Back In Love Again – LTD Good Times – Chic Pick Up the Pieces – Average White Band LeFreak – Chic Take Your Time (Do It Right) ‐ S.O.S. -

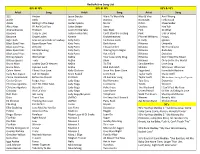

Radioactive Song List

RadioActive Song List 00’s & 10’s 00’s & 10’s 00’s & 10’s Artist Song Artist Song Artist Song 311 Amber Jason Derulo Want To Want Me Nico & Vinz Am I Wrong Adele Hello Jessie J. Domino No Doubt Hella Good Adele Rolling In The Deep Jordan Sparks No Air O.M.I. Cheerleader Alicia Keys If I Ain't Got You Justin Bieber Sorry Outkast Hey Yah Ariana Grande Problem Justin Timberlake Sexy Back Pink So What Beyonce Crazy In Love Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop the Feeling Pink U & Ur Hand Beyonce Single Ladies Karmin Brokenhearted Pharrell Williams Happy Big n Rich Save A Horse Ride A Cowboy Katy Perry California Gurls R. Kelly Igniton Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow Katy Perry Dark Horse Rihanna Umbrella Black Eyed Peas Dirty Bit Katy Perry I Kissed A Girl Rihanna We Found Love Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Katy Perry Waking Up In Vegas Rihanna Rude Boy Black Eyed Peas Imma Be Katy Perry Hot n Cold Rihanna Disturbia Britney Spears Womanizer Ke$ha Your Love Is My Drug Rihanna Don't Stop The Music Britney Spears Toxic Ke$ha Blow Rihanna Only Girl In The World Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Ke$ha Tic Tok Sara Barellies Love Song Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Ke$ha Blah Blah Blah Shakira Whenever Wherever Calvin Harris I Need Your Love Kelly Clarkson Since You Been Gone Sugarland Incredible Machine Carly Rae Jepsen Call me Maybe Kevin Rudolf Let It Rock Taylor Swift Shake It Off Carrie Underwood Before He Cheats Kid Rock All Summer Long Taylor Swift We Are Never Getting Back Together Cee Lo Green Forget You Lady Gaga Bad Romance Taio Cruz Dynamite Christina -

BALLADS JAZZ/BIG BAND FUNK/MOTOWN, 70'S/80'S ROCK TOP 40 DANCE: 90'S - CURRENT

BALLADS JAZZ/BIG BAND FUNK/MOTOWN, 70's/80's ROCK TOP 40 DANCE: 90's - CURRENT A ThousAnd YEArs- ChrisHnA Perri At Last- Etta James Ain't No MountAin High Enough- Marvin GAyE & TAmmi TErrEAll Right Now- Rod StEwArt 24k Magic- Bruno Mars All of Me- John Legend A Wink & A Smile- Harry Connick, JR. Ain't Too Proud To BEg- ThE TemptAHons AmEricAn Girl- Tom PeYy ApAchE- SugAr Hill Gang AmAZEd- Lonestar Blue Bossa- Kenny Dorham All Night Long- LionEl RichiE All SummEr Long- Kid Rock Bad Guy- Billie Eilish Because You LovEd Me- CElinE Dion Come Away With Me- Nora Jones Bad Girls- Donna SummEr Brown EyEd Girl- Van Morrison BlurrEd Lines- Robin Thicke & Pharrell Bless the BrokEn RoAd- RascAl FlAYs Don't Know Why- Nora Jones BEst Of My LovE- ThE EmoHons Don't Stop BeliEving- JournEy Boom Boom Pow- BlAck EyEd PEAs Can't Help Falling In LovE- Elvis PrEslEy Dream A Little Dream of Me- Ella FitzgeraldBoogiE OogiE OogiE- A TAstE of HonEy HArd to HAndlE- BlAck Crowes Bust A MovE- Young MC Could Not Ask For MorE- Edwin McCAin Everything- Michael Buble Brick HousE- ThE CommodorEs Lights- Journey Cake By The Ocean- DNCE CrAZy- PAtsy ClinE Fly Me to the Moon- Frank Sinatra Build Me Up BuYErcup- ThE FoundAHons Livin' On A PrAyEr- Bon Jovi CaliforniA Girls- Katy PErry CrAZy Love- VAn Morrison In the Mood- Glenn Miller BusHn' LoosE- Chuck Brown Lose Your LovE- Ou^ield CAll Me MaybE- CArly RaE JEpsEn ForEvEr Young- Rod StEwArt It Had to be You- Harry Connick, JR. -

1 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat

1 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 5 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 6 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 9 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 10 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 13 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 14 Lady Gaga Poker Face 15 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 16 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 17 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 18 ABBA Dancing Queen 19 Outkast Hey Ya! 20 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 21 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 22 Kool & The Gang Celebration 23 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 24 Sister Sledge We Are Family 25 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 26 Usher Feat. Will.I.Am Omg 27 Beatles Twist And Shout 28 Ke$Ha Tik Tok 29 Jackson, Michael Thriller 30 Lady Gaga Bad Romance 31 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 32 Brown, Chris Forever 33 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 34 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 35 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 36 Isley Brothers Shout 37 James, Etta At Last 38 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 39 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 40 Temptations My Girl 41 Jackson, Michael Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough 42 Commodores Brick House 43 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 44 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 45 Seger, Bob & The Silver Bullet Band Old Time Rock & Roll 46 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Life of the Party

LIFE OF THE PARTY 2021 Song List CONTEMPORARY & DANCE DANCE HITS ● Rolling in the Deep - Adele ● Boogie Oogie Oogie - A Taste of Honey ● Someone Like You - Adele ● I Love the Nightlife - Alicia Bridges ● One and Only - Adele ● If I Ain't Got You - Alicia Keys ● Set Fire to Rain - Adele ● Ring My Bell - Anita Ward ● Til the World Ends - Brittany Spears ● Freeway of Love - Aretha Franklin ● Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepson ● Dr. Feelgood - Aretha Franklin ● Forget You - Cee Lo Green ● Rock Steady - Aretha Franklin ● Turn Up the Music - Chris Brown ● Chain of Fools - Aretha Franklin ● Turn Me On - David Guetta feat. Nick Minaj ● Respect - Aretha Franklin ● I Like It - Enrique Iglesias ● Hello Sunshine - Aretha Franklin ● We Are Young - Fun ● Pick Up the Pieces - Average White Band ● Some Nights - Fun ● Love Shack - B-52's ● Some I Use to Know - Gotye ● I Want to Hold Your Hand - Beatles ● On the Floor - J Lo ● All You Need is Love - Beatles ● Domino - Jessie J ● Come Together - Beatles ● Lovestoned - Justin Timberlake ● Birthday - Beatles ● Just Dance - Lady Gaga ● In My Life - Beatles ● Telephone - Lady Gaga ● Crazy in Love - Beyonce & Destiny's Child ● Poker Face - Lady Gaga ● Deja Vu - Beyonce & Destiny's Child ● What Makes You Beautiful - Lady Gaga ● Survivor - Beyonce & Destiny's Child ● Bad Romance - Lady Gaga ● Halo - Beyonce & Destiny's Child ● I'm Sexy and I Know It - LMFAO ● Love On Top - Beyonce & Destiny's Child ● Party Rock! - LMFAO ● Irreplaceable - Beyonce & Destiny's Child ● Moves Like Jagger - Maroon 5One More Night - ● Single Ladies(Put a Ring On it) - Beyonce Maroon 5 &Destiny's Child ● Just a Dream - Nelly ● Let's Get it Started - Black Eyed Peas ● Starships - Nicki MinajUp All Night - ● Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas ● One Direction ● Hey Mama - Black Eyed Peas ● What Makes You Beautiful - One Direction ● Imma Be - Black Eyed Peas ● Part of Me - Katy Perry ● I Gotta Feeling - Black Eyed Peas ● Teenage Dream - Katy Perry ● Stayin' Alive - The Bee Gees ● E.T. -

Analysis of Grammatical Errors in Pop Song Lyrics

University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice Faculty of Education Department of English Studies Bachelor thesis Analysis of grammatical errors in pop song lyrics Magdalena Smolková Supervisor: Mgr. Ludmila Zemková Ph.D. České Budějovice 2018 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem svoji bakalářskou práci na téma „Analýza gramatických chyb v textech popových písní“ vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě fakultou elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. V Českých Budějovicích dne 23.4.2018 …..………………………… Magdalena Smolková Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala Mgr. Ludmile Zemkové, Ph.D. za vedení, podporu a rady při psaní mé bakalářské práce. Rovněž bych ráda poděkovala Mgr. Jiřímu Kloudovi za korekturu této práce. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Ludmila Zemková, Ph.D. for her guidance, great support and kind advice throughout writing my bachelor thesis. Also, I would like to thank Mgr. Jiří Klouda for correction of this thesis. Anotace Práce bude zkoumat výskyt gramatických chyb v textech písní, řadících se do hudebního žánru pop-music. -

Top 200 Most Requested Songs

Top 200 Most Requested Songs RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 5 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 6 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 9 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 10 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 13 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 14 Lady Gaga Poker Face 15 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 16 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 17 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 18 ABBA Dancing Queen 19 Outkast Hey Ya! 20 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 21 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 22 Kool & The Gang Celebration 23 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 24 Sister Sledge We Are Family 25 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 26 Usher Feat. Will.I.Am Omg 27 Beatles Twist And Shout 28 Ke$Ha Tik Tok 29 Jackson, Michael Thriller 30 Lady Gaga Bad Romance 31 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 32 Brown, Chris Forever 33 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 34 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 35 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 36 Isley Brothers Shout 37 James, Etta At Last 38 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 39 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 40 Temptations My Girl 41 Jackson, Michael Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough 42 Commodores Brick House 43 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 44 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 45 Seger, Bob & The Silver Bullet Band Old Time Rock & Roll 46 Village People Y.M.C.A.