Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06Dem Internationalen Steuerwettbewerb Begegnen

DEM INTERNATIONALEN STEUERWETTBEWERB 06BEGEGNEN I. Motivation II. Der Tax Cuts and Jobs Act und seine Auswirkungen 1. Wesentliche Elemente der Steuerreform 2. Makroökonomische Auswirkungen der Steuerreform III. Deutschland im internationalen Steuerwettbewerb 1. Gewinnsteuersätze international im Abwärtstrend 2. Diskriminierende Besteuerung von mobilen und immobilen Aktivitäten IV. Herausforderungen bei der internationalen Besteuerung 1. Prinzipien zur Festlegung der Besteuerungsrechte 2. Besteuerung der Digitalwirtschaft als Herausforderung 3. Alternative Harmonisierungsbestrebungen V. Steuerpolitische Optionen zur Förderung privater Investitionen 1. Moderate Senkung der Steuerbelastung 2. Abbau von Verzerrungen Eine andere Meinung Literatur Dem internationalen Steuerwettbewerb begegnen – Kapitel 6 DAS WICHTIGSTE IN KÜRZE Zu Beginn des Jahres 2018 wurde in den Vereinigten Staaten mit dem Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) eine umfangreiche Steuerreform umgesetzt, die zum einen die Steuersätze auf Arbeits- und Kapi- taleinkommen deutlich reduziert hat, zum anderen die Besteuerung multinationaler Unternehmen neu ordnet. Dies ist die größte Steuerreform seit dem Tax Reform Act 1986 und dürfte sich in viel- facher Hinsicht auf die Wirtschaft in den Vereinigten Staaten auswirken. Es ist eine zusätzliche Belebung des US-amerikanischen Wirtschaftswachstums zu erwarten, was wiederum das deut- sche Wirtschaftswachstum anregen dürfte. Mit Belgien, Frankreich und Italien haben Staaten mit ehemals höheren Steuersätzen als Deutsch- land ebenfalls die Steuersätze gesenkt und weitere Senkungen angekündigt. Bei den tariflichen Gewinnsteuersätzen rückt Deutschland damit allmählich wieder an die Spitze der OECD-Länder. Die Steuertarife sind jedoch nur ein Bestandteil eines Steuersystems. Die Bemessungsgrundlage, auf die der Steuersatz angewandt wird, ist gleichermaßen von Bedeutung. In diesem Kontext wird unter dem Begriff „Smart Tax Competition“ diskutiert, inwieweit steuerliche Anreize gezielt gesetzt werden können, um bestimmte, sehr mobile Aktivitäten anzuziehen. -

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Microsimulation Model: Documentation and Methodology for Version 0304

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Microsimulation Model: Documentation and Methodology for Version 0304 Jeffrey Rohaly Adam Carasso Mohammed Adeel Saleem January 10, 2005 Jeffrey Rohaly is a research associate at the Urban Institute and director of tax modeling for the Tax Policy Center. Adam Carasso is a research associate at the Urban Institute. Mohammed Adeel Saleem is a research assistant at the Urban Institute. This documentation covers version 0304 of the model, which was developed in March 2004. The authors thank Len Burman and Kim Rueben for helpful comments and suggestions and John O’Hare for providing background on statistical matching. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Urban Institute, the Brookings Institution, their boards, or their sponsors. Documentation and Methodology: Tax Model Version 0304 A. Introduction.................................................................................................................... 3 Overview................................................................................................................................. 3 History..................................................................................................................................... 5 B. Source Data .................................................................................................................... 7 SOI Public Use File ............................................................................................................... -

Tax Administrations and the Challenges of the Digital

LISBON TAX SUMMIT TAX ADMINISTRATIONS AND THE CHALLENGES OF THE DIGITAL WORLD 24 - 26 October 2018 Lisbon, Portugal SUMMARY REPORT LISBON TAX SUMMIT TAX ADMINISTRATIONS AND THE CHALLENGES OF DIGITAL WORLD CONTENTS DAY 1 FAIR AND EFFECTIVE TAXATION ACROSS THE DIGITAL ECONOMY 2 SESSION 1 INAUGURAL SESSION 2 SESSION 2 KEYNOTES: FAIR AND EFFECTIVE TAXATION ACROSS THE DIGITAL ECONOMY 3 SESSION 3 PANEL: HOW TO TAX DIGITAL BUSINESSES - COUNTRIES EXPERIENCES 4 SESSION 4 PANEL: TAX TRANSPARENCY IN THE DIGITAL ERA 6 SESSION 5 ROUND TABLE: DIGITAL TAXATION. IMPLICATIONS, CONCERNS ON THE POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION SIDES 7 SESSION 6 ROUND TABLE: TREATMENT OF CRYPTOCURRENCIES 14 AND INITIAL COIN OFFERINGS 8 DAY 2 MAKING TAX ADMINISTRATION DIGITAL 9 SESSION 7 KEYNOTE: MAKING TAX ADMINISTRATION DIGITAL 9 SESSION 8 PANEL: GETTING CLOSER TO THE FACTS. REAL-TIME CONTROLS FOR TAX ADMINISTRATION PURPOSES 10 SESSION 9 PANEL: PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY 11 SESSION 10 PANEL: HUMAN RESOURCES & CAPACITY BUILDING 13 SESSION 11 ROUND TABLE: TAX AND CUSTOMS DIGITAL ADMINISTRATIONS 14 SESSION 12 PANEL: ADVANCED ANALYTICS FOR COMPLIANCE CONTROL 15 DAY 3 VISION OF THE FUTURE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TAX DIGITIZATION 16 SESSION 13 KEYNOTE: VISION OF THE FUTURE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TAX DIGITIZATION 16 SESSION 14 PANEL: NEW TECHNOLOGIES TO ENHANCE TAX COMPLIANCE AND COLLECTION 17 SESSION 15 PANEL: TAX DIGITIZATION: VIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES OF BUSINESS COMMUNITY 18 SESSION 16 ROUND TABLE: TAX ADMINISTRATION IN 10 - 15 YEARS, HOW ARE WE COPING WITH THE PACE OF -

The Little Downpayment Savings Policy That Could

This article was downloaded by: [George Mason University] On: 27 August 2015, At: 04:02 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Housing and Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhas20 The little downpayment savings policy that could: revisiting building and loan societies and their products in times of the tight credit box and the pending housing finance reform Katrin Anackera a School of Policy, Government and International Affairs, 3351 Fairfax Drive, MSN 3B1, Arlington, VA 22201, USA Published online: 25 Aug 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Katrin Anacker (2015): The little downpayment savings policy that could: revisiting building and loan societies and their products in times of the tight credit box and the pending housing finance reform, Housing and Society, DOI: 10.1080/08882746.2015.1076128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2015.1076128 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. -

2013 Individual Income Tax Rates, Standard Deductions, Personal Exemptions, and Filing Thresholds

15-Oct-15 2016 Individual Income Tax Rates, Standard Deductions, Personal Exemptions, and Filing Thresholds If your filing status is Single If your filing status is Married filing jointly Taxable Income Taxable Income But not But not Over --- over --- Marginal Rate Over --- over --- Marginal Rate $0 $9,275 10% $0 $18,550 10% $9,275 $37,650 15% $18,550 $75,300 15% $37,650 $91,150 25% $75,300 $151,900 25% $91,150 $190,150 28% $151,900 $231,450 28% $190,150 $413,350 33% $231,450 $413,350 33% $413,350 $415,050 35% $413,350 $466,950 35% $415,050 and over 39.6% $466,950 and over 39.6% If your filing status is Married filing If your filing status is Head of Household separately Taxable Income Taxable Income But not But not Over --- over --- Marginal Rate Over --- over --- Marginal Rate $0 $13,250 10% $0 $9,275 10% $13,250 $50,400 15% $9,275 $37,650 15% $50,400 $130,150 25% $37,650 $91,150 25% $130,150 $210,800 28% $91,150 $190,150 28% $210,800 $413,350 33% $190,150 $413,350 33% $413,350 $441,000 35% $413,350 $441,000 35% $441,000 and over 39.6% $441,000 and over 39.6% Standard Deduction Standard Deduction for Dependents Standard Blind/Elderly Greater of $1000 or sum of $350 and Single $6,300 $1,550 individual's earned income Married filing jointly $12,600 $1,250 Personal Exemption $4,050 Head of Household $9,300 $1,550 Married filing Threshold for Refundable separately $6,300 $1,250 Child Tax Credit $3,000 Filing Threshold Number of Blind / Elderly Exemptions 0 1 2 3 4 Single 10,350 11,900 13,450 Head of Household 13,350 14,900 16,450 Married -

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) BEPS Action 7 Additional Guidance on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments 4 October 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AFME and UK Finance .................................................................................................................. 5 Andrew Cousins & Richard Newby ............................................................................................... 8 Andrew Hickman ............................................................................................................................ 13 ANIE (Federazione Nazionale Imprese Elettrotecniche ed Elettroniche) ....................................... 19 Association of British Insurers ....................................................................................................... 22 BDI ...... .......................................................................................................................................... 24 BDO...... .......................................................................................................................................... 26 BEPS Monitoring Group ................................................................................................................ 29 BIAC ... .......................................................................................................................................... 47 BusinessEurope ............................................................................................................................. -

Tax Policy State and Local Individual Income Tax

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK The State of State (and Local) Tax Policy SPECIFIC STATE AND LOCAL TAXES How do state and local individual income taxes work? 1/9 Q. How do state and local individual income taxes work? A. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia levy broad-based taxes on individual income. New Hampshire and Tennessee tax only individual income from dividends and interest. Seven states do not tax individual income of any kind. Local governments in 13 states levy some type of tax on income in addition to the state income tax. State governments collected $344 billion from individual income taxes in 2016, or 27 percent of state own-source general revenue (table 1). “Own-source” revenue excludes intergovernmental transfers. Local governments—mostly concentrated in Maryland, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—collected just $33 billion from individual income taxes, or 3 percent of their own-source general revenue. (Census includes the District of Columbia’s revenue in the local total.) TABLE 1 State and Local Individual Income Tax Revenue 2016 Revenue (billions) Percentage of own-source general revenue State and local $376 16% State $344 27% Local $33 3% Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, “State and Local Finance Initiative Data Query System.” Note: Own-source general revenue does not include intergovernmental transfers. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia levy a broad-based individual income tax. New Hampshire taxes only interest and dividends, and Tennessee taxes only bond interest and stock dividends. (Tennessee is phasing its tax out and will completely eliminate it in 2022.) Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming do not have a state individual income tax. -

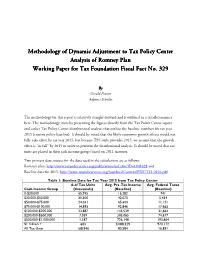

Methodology of Dynamic Adjustment to Tax Policy Center Analysis of Romney Plan Working Paper for Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No

Methodology of Dynamic Adjustment to Tax Policy Center Analysis of Romney Plan Working Paper for Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 329 ByByBy Gerald Prante Adjunct Scholar The methodology for this report is relatively straight-forward and is outlined in a detailed manner here. The methodology starts by presenting the figures directly from the Tax Policy Center report and earlier Tax Policy Center distributional analysis that outline the baseline numbers for tax year 2015 (current policy baseline). It should be noted that the likely economic growth effects would not fully take effect by tax year 2015, but because TPC only provides 2015, we assume that the growth effect is “in full” by 2015 in order to perform the distributional analysis. It should be noted that tax units are placed in their cash income groups based on 2011 incomes. Two primary data sources for the data used in the calculations are as follows: Romney plan: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1001628 and Baseline data for 2015: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/Content/PDF/T12-0126.pdf . Table 1: Baseline Data for Tax Year 2015 from Tax Policy Center # of Tax Units Avg. Pre -Tax Income Avg. Federal Taxes Cash Income Group (thousands) (Baseline) (Baseline) 0-$30,000 65,745 16,282 741 $30,000 -$50,000 30,300 42,073 5,454 $50,000 -$75,000 24,031 65,604 11,121 $75,000 -$100,000 14,893 92,846 17,663 $100,000 -$200,000 23,887 145,539 31,662 $200,000 -$500,000 7,059 305,065 74,677 $500,000 -$1,000,000 1,187 726,148 193,864 $1 million + 603 3,088,329 970,172 All Tax Units 168,946 80,584 16,851 Table 2: Static Distributional Estimates of Romney Plan from TPC Report Avg. -

How Do Federal Income Tax Rates Work? XXXX

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX How do federal income tax rates work? XXXX Q. How do federal income tax rates work? A. The federal individual income tax has seven tax rates that rise with income. Each rate applies only to income in a specific range (tax bracket). CURRENT INCOME TAX RATES AND BRACKETS The federal individual income tax has seven tax rates ranging from 10 percent to 37 percent (table 1). The rates apply to taxable income—adjusted gross income minus either the standard deduction or allowable itemized deductions. Income up to the standard deduction (or itemized deductions) is thus taxed at a zero rate. Federal income tax rates are progressive: As taxable income increases, it is taxed at higher rates. Different tax rates are levied on income in different ranges (or brackets) depending on the taxpayer’s filing status. In TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX How do federal income tax rates work? XXXX 2020 the top tax rate (37 percent) applies to taxable income over $518,400 for single filers and over $622,050 for married couples filing jointly. Additional tax schedules and rates apply to taxpayers who file as heads of household and to married individuals filing separate returns. A separate schedule of tax rates applies to capital gains and dividends. Tax brackets are adjusted annually for inflation. BASICS OF PROGRESSIVE INCOME TAXATION Each tax rate applies only to income in a specific tax bracket. Thus, if a taxpayer earns enough to reach a new bracket with a higher tax rate, his or her total income is not taxed at that rate, just the income in that bracket. -

Table T20-0036 Average Effective Federal Tax Rates -- All Tax Units by Expanded Cash Income Level, 2019 1 Baseline: Current Law

26-Feb-20 PRELIMINARY RESULTS http://www.taxpolicycenter.org Table T20-0036 Average Effective Federal Tax Rates -- All Tax Units By Expanded Cash Income Level, 2019 1 Baseline: Current Law Expanded Cash Tax Units As a Percentage of Expanded Cash Income Income Level (thousands of 2019 Number Percent of Individual 4 Corporate All Federal 3 Payroll Tax Estate Tax Excise Tax 5 dollars)2 (thousands) Total Income Tax Income Tax Taxes Less than 10 12,490 7.2 -4.7 8.0 0.5 0.0 1.6 5.4 10-20 22,010 12.6 -5.8 6.8 0.5 0.0 1.0 2.5 20-30 19,660 11.3 -4.7 7.4 0.6 0.0 0.9 4.2 30-40 15,860 9.1 -2.1 7.7 0.7 0.0 0.8 7.2 40-50 13,250 7.6 0.4 7.6 0.7 0.0 0.8 9.4 50-75 24,800 14.2 2.8 7.8 0.9 0.0 0.7 12.2 75-100 16,610 9.5 5.2 7.8 1.0 0.0 0.7 14.7 100-200 31,760 18.2 7.6 8.3 1.1 0.0 0.6 17.6 200-500 14,360 8.2 11.9 7.5 1.5 0.1 0.5 21.5 500-1,000 1,810 1.0 17.5 4.8 2.0 0.2 0.4 24.9 More than 1,000 830 0.5 23.7 1.9 3.5 0.3 0.3 29.7 All 174,690 100.0 9.9 6.8 1.6 0.1 0.6 18.8 Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Microsimulation Model (version 0319-2). -

EFFECTS of the TAX CUTS and JOBS ACT: a PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS William G

EFFECTS OF THE TAX CUTS AND JOBS ACT: A PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS William G. Gale, Hilary Gelfond, Aaron Krupkin, Mark J. Mazur, and Eric Toder June 13, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper examines the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, the largest tax overhaul since 1986. The new tax law makes substantial changes to the rates and bases of both the individual and corporate income taxes, cutting the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent, redesigning international tax rules, and providing a deduction for pass-through income. TCJA will stimulate the economy in the near term. Most models indicate that the long-term impact on GDP will be small. The impact will be smaller on GNP than on GDP because the law will generate net capital inflows from abroad that have to be repaid in the future. The new law will reduce federal revenues by significant amounts, even after allowing for the modest impact on economic growth. It will make the distribution of after-tax income more unequal, raise federal debt, and impose burdens on future generations. When it is ultimately financed with spending cuts or other tax increases, as it must be in the long run, TCJA will, under the most plausible scenarios, end up making most households worse off than if TCJA had not been enacted. The new law simplifies taxes in some ways but creates new complexity and compliance issues in others. It will raise health care premiums and reduce health insurance coverage and will have adverse effects on charitable contributions and some state and local governments. -

International Trade Policy That Works for U.S. Workers

Washington Center for Equitable Growth | equitablegrowth.org 54 International trade policy that works for U.S. workers By Kimberly A. Clausing, Reed College Overview International trade comes with many benefits for Americans. It lowers the cost and increases the variety of our consumer purchases. It benefits work- ers who make exports, as well as those who rely on imports as key inputs in their work. It helps fuel innovation, competition, and economic growth. And it helps strengthen international partnerships that are crucial for addressing global policy problems. Yet trade also poses risks. Because the United States is a country with large amounts of capital and a highly educated workforce, we tend to specialize in products that use those key resources intensively. That’s why we export complex products such as software, airplanes, and Hollywood movies. Yet we import products that reduce demand for our less-educated labor be- cause countries with lower wages are able to make labor-intensive products more competitively. As a consequence, international trade has harmed many U.S. workers by lowering demand for their labor. Studies find that increased imports, par- ticularly those from China during the early 2000s, displaced more than 1 million U.S. workers.1 There is no evidence that particular trade agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, created any- where near so much displacement, yet many U.S. workers are also skeptical of trade agreements, which they associate with poor labor market out- comes in the U.S. economy over prior decades.2 Indeed, since 1980, the U.S.