Alternatives to War: Eight Things the Us Should Do Regarding Isis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phyllis Bennis

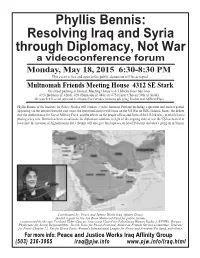

Phyllis Bennis: Resolving Iraq and Syria through Diplomacy, Not War a videoconference forum Monday, May 18, 2015 6:30-8:30 PM This event is free and open to the public; donations will be accepted. Multnomah Friends Meeting House 4312 SE Stark On-street parking is limited; Meeting House is 4-5 blocks from bus lines #15 (Belmont @ 42nd), #20 (Burnside @ 44th) or #75 (Cesar Chavez/39th @ Stark). Or watch it live on ustream.tv/channel/occucakes (remove ads using Firefox and AdBlockPlus) Phyllis Bennis of the Institute for Policy Studies will conduct a video forum in Portland including a question and answer period Appearing via the internet from the east coast, the renowned analyst will focus on the US War on ISIS (/Islamic State), the debate over the Authorization for Use of Military Force, and the effects on the people of Iraq and Syria of the US-led war-- in which Iran is playing a key role. Bennis has been an advocate for diplomatic solutions in light of the ongoing state of war the US has been in at least since the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Bennis will also give brief updates on Israel/Palestine and what's going on in Yemen. Coordinated by: Peace and Justice Works Iraq Affinity Group, funded in part by the Jan Bone Memorial Fund for public forums. cosponsored by Occupy Portland Elder Caucus, Americans United for Palestinian Human Rights (AUPHR), Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, Jewish Voice for Peace-Portland, American Friends Service Committee, Veterans for Peace Chapter 72, Pacific Green Party, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom-Portland, and others. -

U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess They hate our freedoms--our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other (George W. Bush, Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People, September 20, 2001). These values of freedom are right and true for every person, in every society—and the duty of protecting these values against their enemies is the common calling of freedom-loving people across the globe and across the ages (National Security Strategy, September 2002 http://www. whitehouse. gov/nsc/nss. html). The historical connection between U.S. foreign policy and human rights has been strong on occasion. The War on Terror has not diminished but rather intensified that relationship if public statements from President Bush and his administration are to be believed. Some argue that just as in the Cold War, the American way of life as a free and liberal people is at stake. They argue that the enemy now is not communism but the disgruntled few who would seek to impose fundamentalist values on societies the world over and destroy those who do not conform. Proposed approaches to neutralizing the problem of terrorism vary. While most would agree that protecting human rights in the face of terror is of elevated importance, concern for human rights holds a peculiar place in this debate. It is ostensibly what the U.S. is trying to protect, yet it is arguably one of the first ideals compromised in the fight. -

And Pale Odia Palestinian Woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip

and Pale odia Palestinian woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip. Her home was demolished by Israeli military, (p.16) (Photo: Neal Cassidy) nunTHE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE FOR PROGRESSIVE WOMEN VOL. XV SUMMER 1990 PUBLISHER/EDITOR IN CHIEF Merle Hoffman MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Lowy ASSOCIATE EDITOR Eleanor J. Bader ASSISTANT EDITOR Karen Aisenberg EDITOR AT LARGE Phyllis Chester CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Charlotte Bunch Vinie Burrows Naomi Feigelson Chase Irene Davall FEATURES Above: Goats on a porch at Toi Derricotte Mandala. All animals are treated with Roberta Kalechofsky BREAKING BARRIERS: affection and respect, even the skunks. Flo Kennedy WOMEN AND MINORITIES IN (p.10) (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Fred Pelka THE SCIENCES Cover: A single mother and her Helen M. Stummer ON THE ISSUES interviews children find permanency in a H.O.M.E.- ART DIRECTORS Paul E. Gray, President of MIT, and built home. (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Michael Dowdy Dean of Student Affairs, Shirley M. Julia Gran McBay, on sexism and racism in A SONG SO BRAVE — ADVERTISING AND SALES academia 7 PHOTO ESSAY DIRECTOR Text By Phyllis Chesler Carolyn Handel H.O.M.E. Photos By Joan Roth ONE WOMAN'S APPROACH Phyllis Chesler and an international ON THE ISSUES: A feminist, humanist TO SOCIETY'S PROBLEMS group of feminists present a Torah to publication dedicated to promoting By Helen M. Stummer political action through awareness and the women of Jerusalem 19 education; working toward a global Visual sociologist Helen M. Stummer political consciousness; fostering a spirit profiles a unique program to combat TO PEE OR NOT TO PEE of collective responsibility for positive homelessness, poverty and By Irene Davall social change; eradicating racism, disenfranchisement 10 A humorous recollection of the "pee- sexism, ageism, speciesism; and support- in" that forced Harvard to examine its ing the struggle of historically disenfran- FROM STONES TO sexism 20 chised groups to protect and defend STATEHOOD themselves. -

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A. History w/ Departmental Honors ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE A SYSTEM OF DISCRIMINATION COVID-19 IMPACT Given that PalestiniansSTRACT are suffering from As is evident from headlines over the last year, Palestinians are faring much worse While many see the founding of Israel in 1948 as the beginning of discrimination against COVID-19 has amplified all of the existing issues of apartheid, which had put Palestinians the COVID-19 pandemic not only to a under the COVID-19 pandemic than Israelis. Many news sources focus mainly on the Palestinians, it actually extends back to early Zionist colonization in the 1920s. Today, in a place of being less able to fight a pandemic (or any major, global crisis) effectively. greater extent than Israelis, but explicitly present, discussing vaccine apartheid and the current conditions of West Bank, Gaza, discrimination against Palestinians continues at varying levels throughout West Bank, because of discriminatory systems put into and Palestinian communities inside Israel. However, few mainstream news sources Gaza, and Israel itself. Here I will provide some examples: Gaza Because of the electricity crisis and daily power outages in Gaza, medical place by Israel before the pandemic began, have examined how these conditions arose in the first place. My project shows how equipment, including respirators, cannot run effectively throughout the day, and the it is clear that Israel is responsible for taking the COVID-19 crisis in Palestine was exacerbated by existing structures of Pre-1948 When the infrastructure of what would eventually become Israel was first built, constant disruptions in power cause the machines to wear out much faster than they action to ameliorate the crisis. -

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001 DPI TO HOST INTKRNATIONAI, MEDIA ENCOUNTER ON QUESTION OF PALESTINE IN PARIS, 18 - 19 JUNE Search for Peace in Middle East, Role of United Nations To Be Discussed Prominent journalists and Middle East experts, including senior officials and lawmakers from Israel and the Palestinian Authority, will meet at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) headquarters in Paris, on 18 and 19 June, at an international media encounter on the question of Palestine organized by the Department of Public Information (DPI). The overall theme of the encounter is "The search for peace in the Middle East". It is designed as a forum where media representatives and international experts will have an opportunity to discuss the status of the peace process, ways and means to break the deadlock, and the cycle of violence and reporting about the developments in the Middle East. They will also discuss the role of the United Nations in the question of Palestine and in the overall search for peace in the Middle East. The Secretary-General of the United Nations is expected to issue a message welcoming the participants, which will be delivered by Shashi Tharoor, Interim Head, DPI. The Secretary-General of the French Foreign Ministry, Loic Hennekinne, and the Director-General of UNESCO, Koichiro Matsuura, will also welcome the participants. Terje Roed-Larsen, United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process and Personal Representative of the Secretary-General to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Palestinian Authority, will present the keynote address of the encounter, focusing on the peace process in the Middle East. -

Network Against Islamophobia a Project of Jewish Voice for Peace

Network Against Islamophobia A Project of Jewish Voice for Peace Issue No. 2. December 2014 Welcome What JVP Chapters Stories & Strategies: Islamophobia in Hamas is ISIS? What’s in this Have Been Doing to Organizers Speak Out Social Media What People Are newsletter, what is the Challenge Islamophobia An Interview With A Picture Is Worth A Saying About Network Against Updates from Atlanta Bina Ahmad Thousand Words This Meme, Islamophobia, and how and New York City Page 5-7 Page 8 Islamophobia, and to contact us. Page 2-4 Israel Page 1 Page 9-11 Welcome to the 2nd issue of the newsletter for the Network Against Islamophobia (NAI), a project of Jewish Voice for Peace. Since we posted our first newsletter, we have been putting together resources that we hope will be useful both to JVP chapters and to other groups organizing against Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism: FAQs on U.S. Islamophobia & Israel Politics; Resources on Islamophobia & Anti-Arab Racism in the United States; and Challenging the Pamela Geller/American Freedom Defense Initiative (AFDI) Anti-Muslim Ads. Also, check out the Jews Against Islamophobia Coalition’s short video, Jews Recommit to Standing Against Islamophobia, which we’ve posted on the NAI website. This newsletter contains information about some of the organizing against Islamophobia that JVP chapters have been doing. It also highlights the links between Islamophobia and Israel’s latest military campaign in Gaza. In an interview for the newsletter, human rights lawyer and activist Bina Ahmad discusses the impact on the U.S. Muslim community of the summer’s assault and the connection between Islamophobia and Israeli and U.S. -

David Ray Griffin Foreword by Richard Folk

THE NEW PEARL HARBOR Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11 by David Ray Griffin foreword by Richard Folk CONTENTS Acknowledgements vi Forword by Richard Falk vii Introduction xi PART ONE THE EVENTS OF 9 / 11 1. Flights 11 and 175: How Could the Hijackers' Missions Have Succeeded? 3 2. Flight 77: Was It Really the Aircraft that Struck the Pentagon? 25 3. Flight 93: Was It the One Flight that was Shot Down? 49 4. The Presidents Behavior. Why Did He Act as He Did? 57 PART TWO THE LARGER CONTEXT 5. Did US Officials Have Advance Information about 9/11? 67 6. Did US Officials Obstruct Investigations Prior to 9/11? 75 7. Did US Officials Have Reasons for Allowing 9/11? 89 8. Did US Officials Block Captures and Investigations after 9/11? 105 PART THREE CONCLUSION 9. Is Complicity by US Officials the Best Explanation? 127 10. The Need for a Full Investigation 147 Notes 169 Index of Names 210 Back Cover Text OLIVE BRANCH PRESS An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc. Northampton, Massachusetts First published in 2004 by OLIVE BRANCH PRESS An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc. 46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060 www.interlinkbooks.com Text copyright © David Ray Griffin 2004 Foreword copyright © Richard Falk 2004 All rights reserved. No pan of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher unless National Security in endangered and education is essential for survival people and their nation . -

American Air Strikes in Syria Would Do Nothing to Further Justice for The

American Air Strikes in Syria Would Do Nothing to Further Justice for the Victims of the Attack on Douma There is no legal justification for the current US troop presence in Syria, let alone additional air strikes. By Phyllis Bennis, reprint from Donald Trump’s the Prohibition of campaign-era neo- Chemical Weap- isolationism is long ons, the chemical- over. He seems to want weapons watchdog a war now, and if he with a UN mandate can’t have one with and the only inter- North Korea because nationally credible the pesky possibility of agency on this issue, a diplomatic solution announced that its got in the way, Syria team was heading will do, and the recent to Syria and hoped alleged chemical-weap- to begin its inves- ons attack by Bashar tigation in Douma al-Assad’s army on the by April 14. If all city of Douma, near goes well, we may Damascus, seems to get answers to at have provided the pre- Douma, Syria, March 30, 2018. (Reuters / Bassam Khabieh) least some of the text. But war with Syria currently unknown means the potential for war with Iran, and even with nuclear-armed questions: Were chemical weapons definitely used? What Russia—so this is serious. And it’s not just talk. Trump has been were they made of? How were they delivered? Who was assembling a war cabinet and recruiting security advisers—John impacted? We probably won’t learn who was responsible Bolton, Mike Pompeo, Gina Haspel—known for choosing war over in the initial report—the OPCW’s mandate rarely includes LA VOZ diplomacy and torture over international law. -

Obama's First Year

Barely Making the Grade: OBAMA’S FIRST YEAR A Study by the Institute for Policy Studies John Feffer, Dedrick Muhammad, Karen IPS-DC.ORG Dolan, Daphne Wysham, Sarah Anderson and Phyllis Bennis IPS-DC.ORG ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Erik Leaver for layout. Nate Kerksick and Adwoa Masozi for design elements. Contact: Institute for Policy Studies Tel: 202 234 9382 x 227 Email: [email protected] 1112 16th St. NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20036 http://www.ips-dc.org INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES (IPS-DC.ORG) strengthens social movements with independent research, visionary thinking, and links to the grassroots, scholars and elected officials. Since 1963 it has empowered people to build healthy and democratic societies in communities, the United States, and the world. INTRODUCTION BARELY MAKING THE GRADE OBAMA’S FIRST YEAR BY JOHN FEFFER GRADE After the first 100 days of the Obama administra- After the first year in tion, the Institute for Policy Studies introduced our office, Obama fell short Change Index to evaluate the policies and perfor- 6.5 of what he outlined as a mance of the new president. Did the candidate who candidate and what we promised change deliver on his promises? had hoped for during the campaign. Back in April, we gave the administration a score of 7 out of 10. "In other words, President Obama has certainly raised the level of U.S. foreign and After his first year in office, Obama emerged as the domestic policy," we wrote in our report Thirsting "have it both ways" president: hawk and dove, popu- for Change. -

VOICE PO Box 9186, Portland, Oregon 97207 (503) 653-6625 Fosna.Org SEPTEMBER 2009

The OICE Newsletter of Friends of Sabeel—North America VOICE PO Box 9186, Portland, Oregon 97207 (503) 653-6625 fosna.org SEPTEMBER 2009 Get Involved! Sabeel Conference Message from the Chair Washington, DC The Rev. Richard K. Toll, D. Min., D.D. Pursue Justice—Seek Peace: Chairman, Friends of Sabeel—North America Framing the Discourse- Mobilizing for Action October 1—3, 2009 Summer 2009 was a very busy time for Naim and me as we traveled up and down the west coast for a second book tour and the 76th Sabeel Conference General Convention of the Episcopal Church, a ten-day event held in Cedar Falls, Iowa A Free Palestine & A Secure Anaheim, California. We had events in San Diego, Pasadena, Los Israel: From Occupation to Angeles, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle, selling hundreds of Liberation and Reconciliation copies of Naim’s new book, A Palestinian Christian Cry for October 9-10, 2009 Reconciliation . We are so grateful to our dedicated volunteers in all those areas who worked hard putting together book signing events, Sabeel Fall 2009 Witness Trip Palestine/Israel fundraisers, and media opportunities. Below are some pictures of our Sabeel Fall 2009 International booth at the convention (photos by FOSNA volunteer Jim Bettendorf). October 29-November 6, 2009 A real sign of hope is the obvious increase in organized opposition to Sabeel’s message and Sabeel Conference our efforts to turn the tide of opinion toward a just peace in Palestine/Israel. Everywhere Seattle, Washington February 19-20, 2010 we went, those who continue to actively promote only an Israeli view of realities on the ground attempted to vilify Sabeel and Naim. -

Mandate to Discriminate

Mandate to Discriminate Appointing the 2016-2022 UN Special Rapporteur on “Israel’s Violations of the Principles and Bases of International Law” Report by UN Watch March 10, 2016 Geneva, Switzerland Executive Summary Council in the end chose to appoint Mr. Wibisono. The UN Human Rights Council The decision by the plenary is scheduled (UNHRC) is soon to appoint a st replacement for Makarim Wibisono, the to take place at the end of the current 31 former Indonesian diplomat who session of the UNHRC, on Thursday, announced that he will step down March 24, 2016. prematurely, at the end of March 2016, after serving less than two years in his Mandate Against Human Rights position as “Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the The selective, prejudicial and Palestinian territories occupied since discriminatory nature of this mandate has 1967.” been recognized by several of the mandate-holders themselves—including This report examines the controversial former Special Rapporteur Hannu mandate, reviews the 10 applicants, and Halinen—as it negates the very concept of makes recommendations for relevant universal human rights and the rule of stakeholders. law. Appointment Procedure While the title of the mandate implies that the special rapporteur monitors “the Following interviews with five out of the situation of human rights in the ten applicants, the UNHRC’s Palestinian territories,” this is false. In Consultative Group (CG)—chaired by the fact, the text of the mandate, unchanged representative of Egypt— on March 4th since 1993, makes clear that the recommended two names: Penny Green rapporteur is charged with investigating of the UK, ranked first, and Michael Lynk only “Israel’s violations.” of Canada, ranked second. -

Re-Contextualizing the War on Terror

Re-contextualizing The War on Terror Emilie Beck Advisor: Dr. Kari Jensen, Department of Global Studies and Geography Committee: Dr. Zilkia Janer, Department of Global Studies and Geography and Dr. Stefanie E. Nanes, Department of Political Science. Honors Dissertation in Geography, Spring 2018 Hofstra University 2 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Methodology and Positionality .......................................................................................................... 6 Critical Understandings of Space in the Context of Conflict ............................................................ 12 Contextualizing the Spaces of the War on Terror .................................................................................. 12 The ‘Era of Development,’ NeoliBeralism, and U.S. Hegemony ............................................................. 14 Racialized and Orientalist Configurations of Space and Identity ........................................................... 19 The Discursive Construction of the War on Terror .......................................................................... 25 President Bush’s Rhetoric: Us vs. Them, Imaginative Geographies, and Cartographic Performances .. 25 Spaces of InvisiBility and Camouflaged Politics ..................................................................................... 32 Neoliberalizing Space: Foundation and Effects ...............................................................................