The Culture of Learning Disabilities, Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christmas Bowl.Pdf

www.christmasbowl.org A Brand New Bowl Game! The Christmas Bowl™ is a newly proposed postpost--seasonseason college football bowl game, located in Los Angeles, CA. The Christmas Bowl™ location lends itself to some of the largest college football conference followings, as well as one of the nations largest tourist destinations. The Christmas Bowl™ anticipates NCAA approval by April of 2010, and will play the inaugural game the week of Christmas 2010 in one of the most histohistoricalrical stadiums in the world, The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. 3 A New Game Based on Tradition! Bringing a new bowl game to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum has been a vision of Christmas Bowl™ CEO, Derek Dearwater, for almost 10 years. The Christmas Bowl™ name was adopted in recognition of the first postseason bowl game ever played in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum ---- the 1924 Los Angeles Christmas Festival. While the defunct bowl game was only played in 1924, it’s meaningful to the PACPAC--10,10, as it showcased USC defeating a competitive University of Missouri team 2020--7,7, finishing the season with a record of 99--2.2. The 1924 Trojan’s were coached by Elmer Henderson,Henderson, the winningest coach in USC’s history, with a record of 45 --7 (.865). Also present on the field the day of the LA Christmas Festival, was Brice Taylor, USC’s first AllAll--American.American. Scenes from the 1924 Los Angeles Christmas Festival: USC Head Coach USC AllAll--AmericanAmerican The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Elmer "Gloomy Gus" Henderson Brice Taylor in its first year! 4 The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Completed in 1923, Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum is located in the University Park neighborhood of Los Angeles at Exposition Park. -

USC Heisman Salute

USC All-Americans The following is a complete listing of all USC football players who NCAA have ever received first team All-American honors. Although there are 1st 2nd 3rd Con- several teams selected throughout the country, the NCAA now recognizes No. Year Name, Position Team Team Team sensus only seven in determining whether a player is a unanimous or consensus 37 1960 Marlin McKeever, E 1 5 1 choice--AP, Football Coaches Association, Football Writers Association, the Walter Camp Foundation, The Sporting News, CNNSI.com and Football 38 1962 Hal Bedsole, E 10 0 1 X News. 39 1962 Damon Bame, LB 2 0 0 From 1962 to 1990, USC had at least one first team All-American every year. From 1972 to 1987, there was at least one consensus All- 40 1963 Damon Bame, LB 3 1 1 American Trojan every year. Also, there have been 26 first team All- American Trojan offensive linemen since 1964. 41 1964 Bill Fisk, OG 2 2 0 42 1964 Mike Garrett, TB 2 2 0 NCAA 1st 2nd 3rd Con- 43 1965 Mike Garrett, TB 11 0 0 X'H No. Year Name, Position Team Team Team sensus 1 1925 Brice Taylor, G 2 0 0 44 1966 Nate Shaw, DB 8 1 1 X 45 1966 Ron Yary, OT 8 3 0 X 2 1926 Mort Kaer, B 9 0 0 X 3 1927 Morley Drury, B 10 1 0 X 46 1967 O.J. Simpson, TB 11 0 0 X' 4 1927 Jess Hibbs, T 8 1 0 X 47 1967 Ron Yary, OT 11 0 0 X'O 48 1967 Adrian Young, LB 9 2 0 X 5 1928 Jess Hibbs, T 3 0 2 49 1967 Tim Rossovich, DE 5 2 0 X 6 1928 Don Williams, B 2 1 0 50 1968 O.J. -

Extensions of Remarks Hon. John Brademas

November 20, 1974 EXTENSIONS OF R~EMARK.S 36775 stand in adjournment until the hour of able president of the Export-Import ing activities almost without limit while the 12 noon tomorrow. Bank, Mr. Casey. American taxpayer is unable to get financing for his home or his business. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without I think he is an excellent man, and I At the appropriate time, we shall move to objection, it is so ordered. am pleased to work with him. We have a reject the conference report and send it back difference of view on some of these mat to committee for revision. ters pertaining to Export-Import Bank; Rejecion of the conference report will not ORDER FOR THE TRANSACTION OF but so far as the Senator from Virginia close down the Bank. It will only restrict ROUTINE MORNING BUSINESS TO is concerned, the item I am particularly major new transactions until Congress takes MORROW interested in is putting a ceiling on the further action to insure that the Bank oper amount of loans that may be made to ates in the national interest. Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, We urge your support in voting down the I ask unanimous consent that after the Russia. Mr. Casey, the president of the Export-Import Bank Conference Report. two leaders or their designees have been bank, if I judge him accurately, does not Sincerely, recognized under the standing order to want a blank check, but it is the State HARRY F. BYRD, Jr., morrow, there be a period for the trans Department that has insisted upon a JAMES B. -

THE ALUMNUS I; Ii I T the STATE COLLEGE of WASHINGTON T I •

., Published Monthly by the Alumni of the State College of Washington ' l .. ~................. .....- . ................ ..... ...................... ......... ..... ........ ............. ................................................- ................... ...... 1 -- - _ _ • i i ...... + THE ALUMNUS I; Ii i t THE STATE COLLEGE OF WASHINGTON t i • .. f I i i t Volume XV December, 1925, Pullman, W ashington Nwmher 10 t ; ; + . + ----.--..---------..-.......-...------------.------- -- ..................................................................................."........................................................................................................ • • OFFICERS OF THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION 'I< G. H. Gannon, '15, Pullman, Wash. ...................President A. R. Galbraith, '13, Garfield, 'Yash. ........First Vice President • !. J . O. Blair, '08, Vancouver, ·Wash ..... ......Second Vice President Alumni Secretary "' .. H. M. Chambers, '13 . .. ... ... ..... .. .. ....... .Pullman, Wash. Treasurer C. L. Hix, '09 . ... ... .......... ...... ...... ...Pullman, Vvash. Members-at-Large 4 r L. B. Vincent, '15 ................................Yakima, 'Vash. S. Elroy McCaw, '10, .. , ... .... ... .... ... .. ...Bellingham, "Wash. J . H. Binns, '16, .................................Tacoma, "Wash. Ira Clark, '02 ............... ....... .. ... .. Walla Walla, 'Vash. Walter Robinson, '07 .... .. .. ... ................Spokane, ·Wash. (1 ,. Members of Athletic Council I , R. C. McCroskey, '06 ..... ........ ... .. ... ... ..Garfield, -

Download This

Form No. 10-306 <R«v. 10-74) UNITED STATES DtP A RTMt.NT OH THE INTERIOR FOB NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL ff£G/STEff FORMS _______ TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC _Los Angelas Memorial Coliseum________________________________ ANO/OR COMMON Olympic Stadium (1932)_______________________ ____ __________ ILOCATION STREET & NUMBER 3911 S. Ficmeroa Street _NOT FOR PUBUCATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles «OTMM, VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California Los Angeles flCLASSIFICATION i CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT iLpUBUC -^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM — BUILDINGIS) •PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK ^.STRUCTURE *- . —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBUC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT — REUGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RCSTRICTEO —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO •-MILITARY J?OTMER: C Sport S ) AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission STREET & NUMBER 3911 S. Figueroa Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles VICINITY OF California Q0037 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Hall of Records. Log; Anqp>1e>g Tnnntv STREET & NUMBER 320 W. Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE TITLE State Historical Landmark Nomination (DATE May 11, 1934 —FEDERAL }^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY COR SURVEY RECORDS State Historic Preservation Office. CITY. TOWN STATE Sacramento California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CH6CX ONE CHECX ON6- ^.EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED ^UNALTERED £_ORIGINALS1TE _aooo -JUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (Olympic Stadium), situated in Exposition Park, is a reinforced concrete, cast-in-place structure in the form of a giant elliptical bowl.* The ellipse is about 1,038 feet long by 738 feet wide at its midpoint. -

CKLN-FM Mind Control Series Table of Contents

CKLN-FM Mind Control Series Table of Contents Transcripts and tapes are available to buy Updated July 1998 The MCF episode numbering below does not match the tape numbers Search for Get a Free Search Engine for Your Web Site CKLN-FM 88.1 Toronto - International Connection Started March 16, 1997 This is a nine month series; episodes will be added as they occur. CKLN would like to make the show available to other radio stations. For more information or to be put on the transcript e-mail list contact producer Wayne Morris at [email protected] Transcripts and tapes are available at the office of CKLN, 380 Victoria St., Jorgenson Hall, Ryerson University, Toronto, 416-595-1477. Series Announcement 1. The CIA and Military Mind Control Research: Building the Manchurian Candidate - A lecture by Dr. Colin Ross [More by and about Dr. Ross in MindNet] Also see Part 2. 2. Producer Wayne Morris Interviews Dr. Colin Ross. Also see Part 1. 3. Mind Control Survivors' Testimony at the Human Radiation Experiments Hearings 4. Producer Wayne Morris Interviews Ronald Howard Cohen - abducted by the military 5. Interview with Valerie Wolf, Claudia Mullen and Chris deNicola Ebner 6. Lecture by Dr. Alan Scheflin - History of Mind Control 7. Cludia Mullen - Presentation to the Believe the Children Conference, Interview 8. Lecture by Authors Walter Bowart, Alan Scheflin, and Randy Noblitt 9. Lecture by Therapist Valerie Wolf, M.S.W.: Assessment and Treatment of Survivors of Sadistic Abuse 10. Talk by John Rappoport - The CIA, Mind Control, and Children 11. Interview with Valerie Wolf, M.S.W., therapist to trauma and mind control survivors 12. -

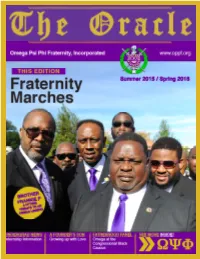

1 the Oracle

The Oracle - Summer 2015/Spring 2016 1 Oracle Editorial Board OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY, INC. Brother Milbert O. Brown, Jr. Editor of The Oracle International Headquarters Email: [email protected] 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 Brother Glenn Rice 404-284-5533 Assistant Editor of The Oracle Brother James Witherspoon The Oracle Director of Photography International Photographer, Chief Volume 86 No. 30 SUMMER 2015/ SPRING 2016 The official publication of District Directors of Public Relations Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. The Oracle is published quarterly 1st Brother Shahid Abdul-Karim 2nd Brother Zanes Cypress, Jr. by Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. 3rd Brother Norman Senior 4th Brother Dr. Fred Aikens at its publications office: 5th Brother D’Wayne Young 6th Brother Kurt Walker 3951 Snapfinger Parkway, Decatur, GA 30035. 7th Brother Barrington Dames 8th Brother Dr. Paul Prosper 9th Brother Avery Matthews 10th Brother Sean Long * The next Oracle deadline: 12th Brother Myron E. Reed 13th Brother Trevor Hodge July 15, 2016 Assistant International Photographers *Deadlines are subject to change. Brother Galvin Crisp Brother Jamal Parker Send address changes to: Brother Wayne Pollard Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Brother John H. Williams, EMERITUS , First International Photographer Attn: Grand KRS 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 Copy Editors and Undergraduate Oracle interns* Brother Vernon A. Battle Brother Jarrett A. Thomas Brother Cedric L. Brown Brother William Haywood, Intern* COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY Brother Dr. Marvin C. Brown, Sr. Brother Jarrett Raghnal, Intern* Bro. James Witherspoon, Director of Photography, International Photographer, Chief International Executive Director COVER DESIGN BY Brother Kenneth Barnes Bro. Craig Spraggins, Psi Alpha Alpha Chapter 40th Grand Basileus Brother Antonio F. -

FALL 2009 Vol

FALSE MEMORY SYNDROME FOUNDATION NEWSLETTER FALL 2009 Vol. 18 No. 4 Dear Friends, television program “Lie to Me” aired a segment in in which “‘Repressed-recovered memories’, ‘dissociative amnesia’ an individual with multiple personalities was encouraged to [3] and related concepts are best described as pernicious psychi- use hypnosis as a way to recover repressed memories. atric folklore devoid of convincing scientific evidence. Such (See page 9 ) The series is about a professor who uses facial theories are quite incapable of reliably assisting the legal expressions to determine if a person is lying. “Lie to Me” process. In our collective opinion, these unsupported, contro- claims to be based on the scientific research of psychologist versial notions have caused incalculable harm to the fields of Paul Ekman, Ph.D., who is a consultant to the show. (See psychology and psychiatry, damaged tens of thousands of page 9.) families, severely harmed the credibility of mental health Following are some comments from the program: professionals, and misled the legislative, civil, criminal, and family legal systems into many miscarriages of justice.” [1] minute 16: Three characters in conversation: “Trisha’s got it, multiple personality disorder...the holy grail of psychiatry...dis- This powerful clear statement is from an amicus[2] brief sociative identity disorder” filed in the Shanley case. The statement is highly significant because it was signed by almost 100 distinguished psychol- minute 19: “In their conscious life the alters aren’t aware of -

Usc's All-Americans

USC’S ALL-AMERICANS The following is a complete listing of all USC football players who NCAA have ever received first team All-American honors. Although there are 1ST 2ND 3RD CON- several teams selected throughout the country, the NCAA now recognizes NO. YEAR NAME, POSITION TEAM TEAM TEAM SENSUS only seven in determining whether a player is a unanimous or consensus 40 1963 Damon Bame, LB 3 1 1 choice--AP, Football Coaches Association, Football Writers Association, the Walter Camp Foundation, The Sporting News, CNNSI.com and 41 1964 Bill Fisk, OG 2 2 0 Football News. 42 1964 Mike Garrett, TB 2 2 0 From 1962 to 1990, USC had at least one first team All-American every year. From 1972 to 1987, there was at least one consensus All- 43 1965 Mike Garrett, TB 11 0 0 X'H American Trojan every year. Also, there have been 27 first team All- American Trojan offensive linemen since 1964. 44 1966 Nate Shaw, DB 8 1 1 X 45 1966 Ron Yary, OT 8 3 0 X NCAA 1ST 2ND 3RD CON- 46 1967 O.J. Simpson, TB 11 0 0 X' NO. YEAR NAME, POSITION TEAM TEAM TEAM SENSUS 47 1967 Ron Yary, OT 11 0 0 X'O 1 1925 Brice Taylor, G 2 0 0 48 1967 Adrian Young, LB 9 2 0 X 49 1967 Tim Rossovich, DE 5 2 0 X 2 1926 Mort Kaer, B 9 0 0 X 50 1968 O.J. Simpson, TB 10 0 0 X'H 3 1927 Morley Drury, B 10 1 0 X 51 1968 Mike Battle, DB 3 2 1 4 1927 Jess Hibbs, T 8 1 0 X 52 1969 Jimmy Gunn, DE 8 1 0 X 5 1928 Jess Hibbs, T 3 0 2 53 1969 Al Cowlings, DT 3 1 0 6 1928 Don Williams, B 2 1 0 54 1969 Sid Smith, OT 4 2 0 55 1969 Clarence Davis, TB 1 1 1 7 1929 Nate Barragar, G-C 1 1 0 8 1929 Francis Tappaan, -

USC Hall of Fame Inductee Charles White)

USC ATHLETIC HALL OF FAME ’94, ’95, ’97, ’99, ’01, ’03, ’05, ’07, ’09, ’12, ‘15 1994 Inductees Jon Arnett (Football, Pre-1960) Clarence “Buster” Crabbe (Swimming) Rod Dedeaux (Coach) Braven Dyer (Media) Mike Garrett (Football, Post-1960) Al Geiberger (Golf) Frank Gifford (Football, Pre-1960) Marv Goux (Special Recognition) Howard Jones (Coach) Fred Lynn (Baseball) John McKay (Coach) Parry O’Brien (Track and Field) Bill Sharman (Basketball) O.J. Simpson (Football, Post-1960) Stan Smith (Tennis) Norman Topping (Special Recognition) JON ARNETT USC Football Known as “Jaguar Jon” because of his outstanding agility, Jon Arnett was a 1955 consensus All-American back at USC as a junior and noted punt/kickoff returner. A three-year starter in football, he also competed on the Trojan track team, placing second in the long jump in the NCAAs in 1954. He graduated from USC with a degree in finance in 1957. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2001. Arnett then played for the Los Angeles Rams (he still holds the team record for the longest kickoff return, 105 yards) for seven years and the Chicago Bears for three years. He was selected to the 1959 All-Pro backfield and played in the Pro Bowl six times. He then became a successful businessman. CLARENCE “BUSTER” CRABBE USC Swimming USC’s first All-American swimmer (1931), Clarence “Buster” Crabbe won an NCAA title in the 440-yard freestyle in 1931 and a gold medal in the 400-meter free at the 1932 Olympics. He also won an AAU individual indoor swimming title in 1932 and the Pacific Coast Conference individual swim title in 1931 in the 220-yard freestyle and the 440-yard freestyle.