The Olympian Ideal of Universal Brotherhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology . 2 Vols. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1977. Collected Writings . 11 Vols. Ed. by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. Campbell, B. 1980. Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement . Berkeley: University of California Press. -

BATMAN Vs SUPERMAN What Would Superman Drive, What Should Batman Drive and Where Could Wonder Woman Store Her Outfit?

WIN A PULSAR BRUCE WAYNE’S JEEP WATCH PEUGEOT ADD FUEL OFFERS WORTH DUCHESS OF CAMBRIDGE PLAYS TENNIS £145 SHORTLISTED FOR NEWSPRESS MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR BATMAN vs SUPERMAN What would Superman drive, what should Batman drive and where could Wonder Woman store her outfit? Your magazine featuring the stars, their cars and more... freecarmag.co.uk 1 FUELLED BY FUN This ISSUEweek 30 / 2016 Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice. We don’t understand why there are a couple of superheroes slugging it out like a wrestling bout, with Wonder Woman watching disapprovingly. However, we are looking forward to making sense of it all very soon at the local multiplex. We’ve got a superhero of our own Free Car Mag, or possibly Margaret, but we are too frightened to call her that. Well she’s more than qualified to tell other superheroes and even super villains what to drive. There is still time to win yourself a brilliant Pulsar watch. All you have to do is sign up to get notification of the latest issue. If you have already signed up, then you are already in with a chance. Tell all your friends and family, because we don’t spam you with nonsense, or pass your details on. We are good like that. 4 News Events Celebs – Made in Chelsea We are also doing very well at the moment. Shortlisted as and Duchess of Cambridge Consumer Magazine and Editor of the Year in the Newspress 6 Batman vs Superman Awards after only being around for a year, it has taken a real 8 Supercars for Superheroes superhuman effort I can tell you. -

The Secret Doctrine Symposium

The Secret Doctrine Symposium Compiled and Edited by David P. Bruce THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P.O. Box 270, Wheaton, IL 60187-0270 www.theosophical.org © 2011 Introduction In creating this course, it was the compiler’s intention to feature some of the most com- pelling and insightful articles on The Secret Doctrine published in Theosophical journals over the past several decades. Admittedly, the process of selecting a limited few from the large number available is to some extent a subjective decision. One of the criteria used for making this selection was the desire to provide the reader with a colorful pastiche of commentary by respected students of Theosophy, in order to show the various avenues of approach to Mme. Blavatsky’s most famous work. The sequence of the articles in the Symposium was arranged, not chronologically, nor alphabetically by author, but thematically and with an eye to a sense of balance. While some of the articles are informational, there are also those that are inspirational, historical, and instructional. It is hoped that the Symposium will encourage, inspire, and motivate the student to begin a serious and sustained exploration of this most unusual and important Theosophical work. Questions have been added to each of the articles. When referring to a specific quote or passage within the article, the page number and paragraph are referenced. For instance, (1.5) indicates the fifth paragraph on page one; (4.2) indicates the second paragraph on page four. A page number followed by a zero, i.e ., (25.0) would indicate that something is being discussed in the paragraph carried over from the previous page, in this case, page 24. -

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

A REFLECTION on the SECRET DOCTRINE, No. 1

January 2012 A REFLECTION ON THE SECRET DOCTRINE , No. 1 The word doctrine may be defined as set of principles or as a body of teachings related to a particular subject. One example from the field of religion would be the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. In the realm of jurisprudence, the doctrine of self-defense is well established. Economists often refer to Marxist or Keynesian doctrines. The military has its doctrines relating to warfare which are studied at West Point and other military academies. A doctrine is something more than a mere idea, or even a concept. For these to be elevated to the status of doctrines, they need to be subjected to a period of intense critical analysis by scholars and experts in that particular field. The principles articulated by Mme. Blavatsky in The Secret Doctrine qualify as doctrines because they are part of a wisdom tradition extending back centuries in time. In his historical introduction to the 1979 edition, Editor Boris de Zirkoff dispenses with the notion that The Secret Doctrine is nothing more than a “syncretistic work wherein a multitude of seemingly unrelated teachings and ideas are cleverly woven together to form a more or less coherent whole” (1:74). It is not difficult to see how a novice reader might arrive at this superficial but erroneous conclusion, given the non-linear style of writing employed by Blavatsky in her magnum opus. To the student possessing a measure of intuitive capacity, deep and sustained consideration will reveal The Secret Doctrine to be “a wholly coherent outline of an ageless doctrine, a system of thought based upon occult facts and universal truths inherent in nature and which are as specific and definite as any mathematical proposition” (1:74). -

“History of Education Society Bulletin” (1985)

History of Education Society Bulletin (1985) Vol. 36 pp 52 -54 MONTESSORI WAS A THEOSOPHIST Carolie Wilson Dept. of Education, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia In October 1947 Time magazine reported that world famous education- ist Dr. Maria Montessori, though 'almost forgotten', was none the less very much alive in India where she was continuing to give lectures in the grounds of the Theosophical Society's magnificent estate at Adyar on the outskirts of Madras. 1 Accompanied by her son Mario, Montessori had gone to India at the invitation of Theosophical Society President, George Arundale, in No- vember 1939 and had been interned there as an 'enemy alien' when Italy en- tered the Second World War in June 1940. The Dottoressa was permitted however, to remain at Adyar to continue her teacher training courses and later to move to a more congenial climate in the hills at Kodaikanal. 2 At the end of the War she made a short visit to Europe but returned to India to undertake the first teacher training course at the new Arundale Montessori Training Centre.3 The Centre was established as a memorial to former Theosophi- cal Society President, Dr. Annie Besant, whose centenary was being celebrat- ed at Adyar in October 1947.4 In view, no doubt, of her continued residence at Adyar and the gener- ous support the Theosophical Society extended to Montessori and Mario during the War years, the Dottoressa was asked on one occasion under the shade of the famous giant banyan tree at Adyar, whether she had in fact become a Theosophist. -

The Third Object of the Theosophical Society

March 2011 THE THIRD OBJECT OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY To investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity. ― Third Object of the Theosophical Society The wording of the Theosophical Society’s three Objects was revised a number of times during the early years of the Society, but they have remained essentially unchanged since 1896. Many of our members associate this Object primarily with psychic powers such as clairvoyance, clairaudience, precognition, telepathy and the like. Certainly the scope of the third Object includes these types of interesting phenomena, but it really goes much deeper than that. In the March 1953 issue of The American Theosophist (AT) , seventy-eight years after the founding of the Society, the Theosophical writer Rohit Mehta observed, “We have yet to understand the full significance of the third Object.” Oddly enough, this may still be the case today. Over the years, deep students of Theosophy have given us hints as to the inner meaning of the third Object. In Human Regeneration , Radha Burnier suggests that “we must see the connection between the three Objects . to the unfoldment of the human consciousness.” In the October 1970 issue of the AT , Joy Mills suggested that the third Object relates to both “a way of knowing” and “a way of living.” By knowing she meant, not an accumulation of intellectual data, but rather a “process of inner comprehension.” Another insight was given by Hugh Shearman in his AT article of June 1949: “Occult truths are never hidden from us by anybody. We reveal or conceal them ourselves individually by what we are and what we are not yet.” In other words, the methods used to gain ordinary knowledge are not sufficient to compre- hend the hidden laws of nature and unfold the latent powers within. -

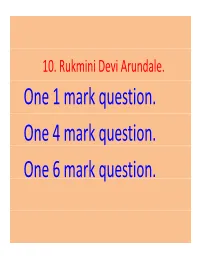

One 1 Mark Question. One 4 Mark Question. One 6 Mark Question

10. Rukmini Devi Arundale. One 1 mark question. One 4 mark question. One 6 mark question. Content analysis About Rukmini Devi Arundale. Born on 29‐02‐1904 Father Neelakantha StiSastri Rukmini Devi Arundale Rukmini Devi Liberator of classical dance. India’s cultural queen. Rukmini Devi Fearless crusader for socilial c hange. Champion of vegetarianism. Andhra art of vegetable-dyed Kalmakari Textile crafts like weaving silk an d cotton a la (as prepared in) Kanchipuram Banyan tree at Adyar Rukmini Devi The force that shaped the future of Rukmini Devi Anna Pavlova Anna Pavlova Wraith-like ballerina (Wraith-like =otherworldly) Her meeting with Pavlova. First meeting : In 1924, in London at the Covent Gardens. Her meeting with Pavlova. Second meeting: Time : At the time of annual Theosophical Convention at Banaras. Place : Bombay - India. The warm tribute of Pavlova Rukmini Devi: I wish I could dance like you, but I know I never can. The warm tribute of Pavlova Anna Pavlova:NonoYoumust: No, no. You must never say that. You don’t have to dance, for if you just walk across the stage, it will be enouggph. People will come to watch you do just that. Learning Sadir. She learnt Sadir, the art of Devadasis . Hereditary guru : Meenakshisundaram Pillai. Duration: Two years. First performance At the International Theosophical Conference Under a banyan tree In 1935. reaction Orthodox India was shocked . The first audience adored her revelatory debut. The Bishop of Madras confessed that he felt like he had attended a benediction. Liberating the Classical dance. Changes made to Sadir. Costume and jewellery were of good taste. -

Painting the Masters. the Mystery of Hermann Schmiechen

Painting the Masters The Mystery of Hermann Schmiechen Massimo Introvigne (UPS, Torino, Italy) Besançon’s Forbidden Image One of the first books where sociology of religion met history of art was L’image interdite. Une histoire intellectuelle de l’iconoclasme, published by French social historian Alain Besançon in 1994 Iconoclasm vs Iconodulism The controversial book argued that Western art history is defined by opposition between iconoclasm (i.e the idea that the sacred should not be represented visually) and iconodulism (i.e support for sacred images) Although the terminology dates back to the Byzantine iconoclastic riots of the 8th century (right), modern Western iconoclasm originated with John Calvin (1509-1564) and became culturally dominant after the Enlightenment Iconoclasm: not against art, but against an art representing God or divine spirits Besançon’s definition of iconoclasm is not identical with some dictionary definitions of the same word. For him, iconoclasm is not against art and may even promote it. It only excludes from the field of art the representation of God and divine spirits or beings Image of Byzantine Emperor Leo III (685-741) on a coin: Leo, a leading iconoclast, was obviously not against representing himself Abstract Art as Iconoclasm Besançon* also argued that: 1. Iconoclasm is a distinctive trait of modernity, and abstract art is its most mature fruit 2. Symbolism, at first sight anti-iconoclastic, by substituting the Christian foundations of sacred art with a very different esoteric spirituality, in fact prepared the way for abstract iconoclasm 3. Several abstract painters, including Piet Mondrian (1872- 1944) passed at one stage through symbolism (Evolution, 1910-1911, left) * … with whom I do not necessarily agree Besançon and Theosophy Besançon claimed to be among the first social historians to devote serious attentions to Madame Blavatsky (1831-1891) and other Theosophical classics. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 135 NO. 7 APRIL 2014 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 M. P. Singhal The many lives of Siddhartha 7 Mary Anderson The Voice of the Silence — II 13 Clara Codd Charles Webster Leadbeater and Adyar Day 18 Sunita Maithreya Regenerating Wisdom 21 Krishnaphani Spiritual Ascent of Man in Secret Doctrine 28 M. A. Raveendran The Urgency for a New Mind 32 Ricardo Lindemann International Directory 38 Editor: Mr M. P. Singhal NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: Common Hoope, Adyar —A. Chandrasekaran Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. 1 THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Vice-President: Mr M. P. Singhal Secretary: Dr Chittaranjan Satapathy Treasurer: Mr T. S. Jambunathan Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Society’s Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. Their bond of union is not the profession of a common belief, but a common search and aspiration for Truth. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Why Wonder Woman Matters

Why Wonder Woman Matters When I was a kid, being a hero seemed like the easiest thing in the world to be- A Blue Beetle quote from the DC Comics publication The OMAC Project. Introduction The superhero is one of modern American culture’s most popular and pervasive myths. Though the primary medium, the comic book, is often derided as juvenile or material fit for illiterates the superhero narrative maintains a persistent presence in popular culture through films, television, posters and other mediums. There is a great power in the myth of the superhero. The question “Why does Wonder Woman matter?” could be answered simply. Wonder Woman matters because she is a member of this pantheon of modern American gods. Wonder Woman, along with her cohorts Batman and Superman represent societal ideals and provide colorful reminders of how powerful these ideals can be.1 This answer is compelling, but it ignores Wonder Woman’s often turbulent publication history. In contrast with titles starring Batman or Superman, Wonder Woman comic books have often sold poorly. Further, Wonder Woman does not have quite the presence that Batman and Superman both share in popular culture.2 Any other character under similar circumstances—poor sales, lack of direction and near constant revisions—would have been killed off or quietly faded into the background. Yet, Wonder Woman continues to persist as an important figure both within her comic universe and in our popular consciousness. “Why does Wonder Woman matter?” To answer this question an understanding of the superhero and their primary medium, the comic book, is required, Wonder Woman is a comic book character, and her existence in the popular consciousness largely depends on how she is presented within the conventions of the comic book superhero narrative.