Botanical Briefs: Ylang-Ylang Oil— Extracts from the Tree Cananga Odorata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

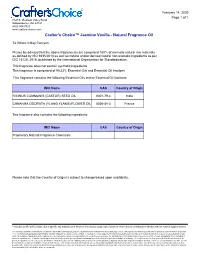

Crafter's Choice™ Jasmine Vanilla

February 14, 2020 Page 1 of 1 7820 E. Pleasant Valley Road Independence, OH 44131 (800) 908-7028 www.crafters-choice.com Crafter’s Choice™ Jasmine Vanilla - Natural Fragrance Oil To Whom it May Concern, Please be advised that the above fragrance(s) are comprised 100% of aromatic natural raw materials as defined by ISO 9235:2013 as well as natural and/or derived natural non-aromatic ingredients as per ISO 16128: 2016, published by the International Organization for Standardization. This fragrance does not contain synthetic ingredients. This fragrance is comprised of 90.33% Essential Oils and Essential Oil fractions This fragrance contains the following Essential Oils and/or Essential Oil fractions: INCI Name CAS Country of Origin RICINUS COMMUNIS (CASTOR) SEED OIL 8001-79-4 India CANANGA ODORATA (YLANG YLANG) FLOWER OIL 8006-81-3 France This fragrance also contains the following ingredients: INCI Name CAS Country of Origin Proprietary Natural Fragrance Chemicals Please note that the Country of Origin is subject to change based upon availability. * indicates unofficial INCI name, due to specific raw material used. However, the most accurate name has been chosen based on industry knowledge and raw material supplier names. The information and data contained in this document are presented for informational purposes only and have been obtained from various third party sources. Although we have made a good faith effort to present accurate information as provided to us, our ability to independently verify information and data obtained from outside sources is limited. To the best of our knowledge, the information presented herein is accurate as of the date of publication, however, it is presented without any other representation or warranty as to its completeness or accuracy and we assume no responsibility for its completeness or accuracy. -

Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities of Cananga Odorata (Ylang-Ylang)

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2015, Article ID 896314, 30 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/896314 Review Article Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities of Cananga odorata (Ylang-Ylang) Loh Teng Hern Tan,1 Learn Han Lee,1 Wai Fong Yin,2 Chim Kei Chan,3 Habsah Abdul Kadir,3 Kok Gan Chan,2 and Bey Hing Goh1 1 JeffreyCheahSchoolofMedicineandHealthSciences,MonashUniversityMalaysia,46150BandarSunway, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia 2Division of Genetic and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Science, Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 3Biomolecular Research Group, Biochemistry Program, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Correspondence should be addressed to Bey Hing Goh; [email protected] Received 30 April 2015; Revised 4 June 2015; Accepted 9 June 2015 AcademicEditor:MarkMoss Copyright © 2015 Loh Teng Hern Tan et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Ylang-ylang (Cananga odorata Hook. F. & Thomson) is one of the plants that are exploited at a large scale for its essential oil which is an important raw material for the fragrance industry. The essential oils extracted via steam distillation from the plant have been used mainly in cosmetic industry but also in food industry. Traditionally, C. odorata is used to treat malaria, stomach ailments, asthma, gout, and rheumatism. The essential oils or ylang-ylang oil is used in aromatherapy and is believed to be effective in treating depression, high blood pressure, and anxiety. -

Drupe. Fruit with a Hard Endocarp (Figs. 67 and 71-73); E.G., and Sterculiaceae (Helicteres Guazumaefolia, Sterculia)

Fig. 71. Fig. 72. Fig. 73. Drupe. Fruit with a hard endocarp (figs. 67 and 71-73); e.g., and Sterculiaceae (Helicteres guazumaefolia, Sterculia). Anacardiaceae (Spondias purpurea, S. mombin, Mangifera indi- Desmopsis bibracteata (Annonaceae) has aggregate follicles ca, Tapirira), Caryocaraceae (Caryocar costaricense), Chrysobal- with constrictions between successive seeds, similar to those anaceae (Licania), Euphorbiaceae (Hyeronima), Malpighiaceae found in loments. (Byrsonima crispa), Olacaceae (Minquartia guianensis), Sapin- daceae (Meliccocus bijugatus), and Verbenaceae (Vitex cooperi). Samaracetum. Aggregate of samaras (fig. 74); e.g., Aceraceae (Acer pseudoplatanus), Magnoliaceae (Liriodendron tulipifera Hesperidium. Septicidal berry with a thick pericarp (fig. 67). L.), Sapindaceae (Thouinidium dodecandrum), and Tiliaceae Most of the fruit is derived from glandular trichomes. It is (Goethalsia meiantha). typical of the Rutaceae (Citrus). Multiple Fruits Aggregate Fruits Multiple fruits are found along a single axis and are usually coalescent. The most common types follow: Several types of aggregate fruits exist (fig. 74): Bibacca. Double fused berry; e.g., Lonicera. Achenacetum. Cluster of achenia; e.g., the strawberry (Fra- garia vesca). Sorosis. Fruits usually coalescent on a central axis; they derive from the ovaries of several flowers; e.g., Moraceae (Artocarpus Baccacetum or etaerio. Aggregate of berries; e.g., Annonaceae altilis). (Asimina triloba, Cananga odorata, Uvaria). The berries can be aggregate and syncarpic as in Annona reticulata, A. muricata, Syconium. Syncarp with many achenia in the inner wall of a A. pittieri and other species. hollow receptacle (fig. 74); e.g., Ficus. Drupacetum. Aggregate of druplets; e.g., Bursera simaruba THE GYMNOSPERM FRUIT (Burseraceae). Fertilization stimulates the growth of young gynostrobiles Folliacetum. Aggregate of follicles; e.g., Annonaceae which in species such as Pinus are more than 1 year old. -

Amendment 49 STAND Benzyl Alcohol

IFRA Amendment 49 IFRA STANDARD STANDARD Benzyl alcohol CAS-No.: 100-51-6 Molecular C7H8O The scope of this Standard formula: includes, but is not limited to the CAS number(s) indicated Structure: above; any other CAS number(s) used to identify this fragrance ingredient should be considered in scope as well. Synonyms: Benzenemethanol Benzylic alcohol α-Hydroxytoluene Phenylcarbinol Phenyl carbinol Phenylmethanol Phenylmethyl alcohol α-Toluenol History: Publication date: 2020 (Amendment 49) Previous 2007 Publications: Implementation For new submissions*: February 10, 2021 dates: For existing fragrance compounds*: February 10, 2022 *These dates apply to the supply of fragrance mixtures (formulas) only, not to the finished consumer products in the marketplace. RECOMMENDATION: RESTRICTION RESTRICTION LIMITS IN THE FINISHED PRODUCT (%): Category 1 0.45 % Category 7A 0.68 % Category 2 0.14 % Category 7B 0.68 % Category 3 0.34 % Category 8 0.057 % Category 4 2.5 % Category 9 2.2 % 2020 (Amendment 49) 1/5 IFRA Amendment 49 IFRA STANDARD STANDARD Benzyl alcohol Category 5A 0.64 % Category 10A 2.2 % Category 5B 0.17 % Category 10B 8.5 % Category 5C 0.34 % Category 11A 0.057 % Category 5D 0.057 % Category 11B 0.057 % Category 6 1.5 % Category 12 No Restriction FLAVOR REQUIREMENTS: Due to the possible ingestion of small amounts of fragrance ingredients from their use in products in Categories 1 and 6, materials must not only comply with IFRA Standards but must also be recognized as safe as a flavoring ingredient as defined by the IOFI Code of Practice (www.iofi.org). For more details see chapter 1 of the Guidance for the use of IFRA Standards. -

Annonacin in Asimina Triloba Fruit : Implications for Neurotoxicity

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 Annonacin in Asimina triloba fruit : implications for neurotoxicity. Lisa Fryman Potts University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Potts, Lisa Fryman, "Annonacin in Asimina triloba fruit : implications for neurotoxicity." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1145. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1145 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANNONACIN IN ASIMINA TRILOBA FRUIT: IMPLICATIONS FOR NEUROTOXICITY 8y Lisa Fryman Potts 8.S. Centre College, 2005 M.S. University of Louisville, 2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Medicine at the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anatomical Sciences and Neurobiology University of Louisville School of Medicine Louisville, Kentucky December 2011 Copyright 2011 by lisa Fryman Potts All rights reserved ANNONACIN IN ASIMINA TRILOBA FRUIT: IMPLICATIONS FOR NEUROTOXICITY By Lisa Fryman Potts B.S. Centre College, 2005 M.S. University of Louisville, 2010 A Dissertation Approved on July 21, 2011 by the following Dissertation Committee: Irene Litvan, M.D. Dissertation Director Frederick Luzzio, Ph.D. Michal Hetman, M.D., Ph.D. -

Early Floral Developmental Studies in Annonaceae

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Biosystematics and Ecology Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 10 Autor(en)/Author(s): Leins Peter, Erbar Claudia Artikel/Article: Early floral developmental studies in Annonaceae. In: Reproductive Morphology in Annonaceae. 1-28 Early floral developmental©Akademie d. Wissenschaften studies Wien; download in unter Annonaceae www.biologiezentrum.at Peter LEINS and Claudia Erba r Abstract: In theAnnonaceae the perianth mostly consists of three trimerous whorls, with a slight tendency to a spiral sequence of their members. The androecium and the gynoecium are variable in the number of their organs (high polymery to low, fixed numbers). In this study the early development of polymerous androecia is investigated Artabotrysin hexapetalus andAnnona montana. In these species the androecia begin their development with six stamens in the comers of a hexagonal floral apex. This early developmental pattem resembles that in someAristolochiaceae andAlismatales. Not only in this respect but also because of other important features theAnnonaceae may be regarded as closely related to these two groups, but as more archaic. The carpels in the mostly choricarpous gynoecia areconduplicate (not peltate) or very rarely (Cananga) slightly peltate. The gynoecium ofMonodora consists of a single, clearly peltate carpel with a very peculiar laminal placentation (the ovules are inserted in seven double rows). This unusual condition can be interpreted as the expression sequentialof two genetical programs during development: the program for a single carpel and that for a pluricarpellate gynoecium(Simulation of a syncarpous gynoecium). Introduction - Morphology of the adult flowers The familiy Annonaceae, with about 130 genera and 2300 species by far the largest family of the Magnoliales, makes up about three-fourths of the order (CRONQUIST 1981). -

Natural History Guide to American Samoa

NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE TO AMERICAN SAMOA rd 3 Edition NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE This Guide may be available at: www.nps.gov/npsa Support was provided by: National Park of American Samoa Department of Marine & Wildlife Resources American Samoa Community College Sport Fish & Wildlife Restoration Acts American Samoa Department of Commerce Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, University of Hawaii American Samoa Coral Reef Advisory Group National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Natural History is the study of all living things and their environment. Cover: Ofu Island (with Olosega in foreground). NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE TO AMERICAN SAMOA 3rd Edition P. Craig Editor 2009 National Park of American Samoa Department Marine and Wildlife Resources Pago Pago, American Samoa 96799 Box 3730, Pago Pago, American Samoa American Samoa Community College Community and Natural Resources Division Box 5319, Pago Pago, American Samoa NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE Preface & Acknowledgments This booklet is the collected writings of 30 authors whose first-hand knowledge of American Samoan resources is a distinguishing feature of the articles. Their contributions are greatly appreciated. Tavita Togia deserves special recognition as contributing photographer. He generously provided over 50 exceptional photos. Dick Watling granted permission to reproduce the excellent illustrations from his books “Birds of Fiji, Tonga and Samoa” and “Birds of Fiji and Western Polynesia” (Pacificbirds.com). NOAA websites were a source of remarkable imagery. Other individuals, organizations, and publishers kindly allowed their illustrations to be reprinted in this volume; their credits are listed in Appendix 3. Matt Le'i (Program Director, OCIA, DOE), Joshua Seamon (DMWR), Taito Faleselau Tuilagi (NPS), Larry Basch (NPS), Tavita Togia (NPS), Rise Hart (RCUH) and many others provided assistance or suggestions throughout the text. -

Improvement of Ylang-Ylang Essential Oil Characterization by GC×GC-TOFMS

Molecules 2013, 18, 1783-1797; doi:10.3390/molecules18021783 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Article Improvement of Ylang-Ylang Essential Oil Characterization by GC×GC-TOFMS Michał Brokl 1,†, Marie-Laure Fauconnier 2,†, Céline Benini 2, Georges Lognay 3, Patrick du Jardin 2 and Jean-François Focant 1,* 1 Chemistry Department—CART, Organic and Biological Analytical Chemistry, University of Liège, Allée du 6 Août B6c, Liège B-4000, Belgium; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Plant Biology Unit, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, University of Liège, Passage des Déportés 2, Gembloux B-5030, Belgium; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.-L.F.); [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (P.J.) 3 Analytical Chemistry Laboratory-CART, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, University of Liège, Passage des des Déportés 2, Gembloux B-5030, Belgium; E-Mail: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-(0)-4-366-3531; Fax: +32-(0)-4-366-4387. Received: 11 December 2012; in revised form: 24 January 2013 / Accepted: 25 January 2013 / Published: 30 January 2013 Abstract: A single fraction of essential oil can often contain hundreds of compounds. Despite of the technical improvements and the enhanced selectivity currently offered by the state-of-the-art gas chromatography (GC) and mass spectrometry (MS) instruments, the complexity of essential oils is frequently underestimated. Comprehensive two-dimensional GC coupled to time-of-flight MS (GC×GC-TOFMS) was used to improve the chemical characterization of ylang-ylang essential oil fractions recently reported in a previous one-dimensional (1D) GC study. -

Avifaunas of the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains, Indonesian New Guinea

Jared Diamond & K. David Bishop 292 Bull. B.O.C. 2015 135(4) Avifaunas of the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains, Indonesian New Guinea by Jared Diamond & K. David Bishop Received 13 February 2015 Summary.—Of the 11 outlying mountain ranges along New Guinea’s north and north-west coasts, the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains are those most isolated from the Central Range and from other outliers by flat lowlands almost at sea level. The Kumawa Mountains were previously unexplored ornithologically, and the Fakfak Mountains unexplored above 900 m. We report four surveys conducted in 1981, 1983 and 2013. The known combined avifauna is now 283 species, including 77 upland species of which the two ranges share at least 57. Among Central Range upland species whose geographic and altitudinal ranges make them plausible candidates to have colonised Fakfak and Kumawa, 15 are nevertheless unrecorded in both Fakfak and Kumawa. Of those 15, 13 are also unrecorded in the mountains of Yapen Island, which at Pleistocene times of low sea level was also separated from other New Guinea mountains by a wide expanse of flat lowlands. This suggests that colonisation of isolated mountains by those particular upland species depends on dispersal through hilly terrain, and that they do not disperse through flat lowland forest. Because of the low elevation, small area and coastal proximity of the Kumawa and Fakfak Mountains, avian altitudinal ranges there show the largest Massenerhebung effect (lowering) of any New Guinea mainland mountains known to us. We compare zoogeographic relations of the Fakfak and Kumawa avifaunas with the mountains of the Vogelkop (the nearest outlier) and with the Central Range. -

Cananga Cananga Odorata 15 Ml PRODUCT INFORMATION PAGE

Cananga Cananga odorata 15 mL PRODUCT INFORMATION PAGE PRODUCT DESCRIPTION The yellow flowers of the Cananga tree, native to tropical Asia, have been used in traditional practices for centuries. Today, Indonesians still place Cananga flowers on honeymooners’ pillows to symbolize the start of a happy union. Cananga’s rich history and powerful benefits are largely due to its high concentration of beta-caryophyllene, which is a topically soothing chemical constituent found in many essential oils including Frankincense, Copaiba, and Ylang Ylang. Applied topically, Cananga has renewing properties that can rejuvenate the appearance of skin. The light, floral scent of Cananga can have a calming and elevating effect when diffused. USES Certified Pure Tested Grade® Cosmetic • Add two to three drops to Epsom salts for a soothing and Application: relaxing bath experience. Plant Part: Flower • Add one to two drops to daily moisturizer to help enhance Extraction Method: Steam distillation skin’s appearance. Aromatic Description: Warm, sweet, flowery, and • Add a few drops to hand and body lotion and apply to woody desired area for a soothing, rejuvenating massage. Main Chemical Components: β-Caryophyllene Germacrene D Household • Diffuse for a calming, peaceful aroma. Cananga • Add a few drops to aromatherapy jewelry for an uplifting Cananga odorata 15 mL aroma. Available during July 2019 Promo. DIRECTIONS FOR USE Diffusion: Use three to four drops in the diffuser of choice. Topical use: Apply one to two drops to desired area. Dilute with a carrier oil to minimize any skin sensitivity. CAUTIONS For external use only. Possible skin sensitivity. Keep out of reach of children. -

Developmental Patterns in Stem Primary Xylem Of

August, 1967] BENZING-PRIMARY XYLEM OF RANALES. II. 813 ESAU, K. 1965a. Vascular differentiation in plants. gymnosperms. Ph.D. thesis. University of Michigan, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Ann Arbor. 1965b. Plant anatomy. 2nd ed. John Wiley MONEY, L. L., I. W. BAILEY, AND B. G. SWAMY. 1950. and Sons, Inc., New York. The morphology and relationships of the Moni EZELARAB, G. E., AND K. J. DORMER. 1963. The miaceae. J. Arnold Arbor. 31: 372-404. organization of the primary vascular system in the PHILIPSON, W. R., AND E. E. BALFOUR. 1963. Vascular Ranunoulaoeae. Ann. Bot. 27: 23-38. patterns in dicotyledons. III. Anatomy of the stem FAHN, A., AND I. W. BAILEY. 1957. The nodal anatomy of Calycanthaceae. Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinb. 52: and the primary vascular cylinder of the Calycan 517-530. thaceae. J. Arnold Arbor. 38: 107-117. QUINLAN, C. E. 1920. Contributions towards a knowl JACOBS, W. P., AND I. B. MORROW. 19,'')7. A quantita edge of the anatomy of the lower dicotyledons. III. tive study of xylem development in the vegetative Anatomy of the stem of Calycanthaceae. Trans. shoot apex of Coleus. Amer, J. Bot. 44: 823-842. Roy. Soc. Edinb. 52: 517-530. JEFFREY, E. C. 1917. The anatomy of woody plants. WETMORE, R. H., AND C. W. WARDLAW. 1951. Experi University of Chicago Press. mental morphogenesis in vascular plants. Ann. Rev. KUMARI, G. K. 1963. The primary vascular system of Plant Physiol. 2: 269-292. Arner. J. But. 54(7): 813-820. 1967. DEVELOP1VlENTAL PATTERNS IN STEM: PRIMARY XYLEM OF 'WOODY RANALES. -

Product Catalogue 2021 CONTENTS

Naturally Australian Products & NAP Global Essentials Product Catalogue 2021 CONTENTS CATEGORIES PAGE 1. Conventional Essential Oils ____________________________________________ 3 2. Conventional Absolutes _____________________________________________ 10 3. Conventional CO2 Extractions _________________________________________ 11 4. Conventional Hydrosols ______________________________________________ 12 5. Conventional Australian Seed Oils ____________________________________ 13 6. Conventional Australian Oil Infusions __________________________________ 13 7. Conventional Carrier and Seed Oils _____________________________________ 13 8. Organic Essential Oils _______________________________________________ 16 9. Organic CO2 Extractions ___________________________________________ 20 10. Organic Hydrosols ________________________________________________ 22 11. Organic Carrier Oils and Seed Oils ___________________________________ 23 12. Exotic Native Australian Cellular Extracts - Concentrate and Standard __ 25 13. Fruit and Vegetable Cellular Extracts - Concentrate and Standard ______ 26 14. Traditional Cellular Extracts - Concentrate and Standard ______________ 27 15. Advanced Floral Cellular Extracts - Concentrate and Standard _________ 28 16. Powdered Extracts ________________________________________________ 29 17. Conventional Powders - Food Grade and Cosmetic _______________ 30 18. Organic Powders - Food Grade and Cosmetic ___________________ 32 19. Waxes ___________________________________________________________ 33 20. Exfoliants