AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Robert Frank Koontz for the Ph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lehman Caves Management Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Great Basin National Park Lehman Caves Management Plan June 2019 ON THE COVER Photograph of visitors on tour of Lehman Caves NPS Photo ON THIS PAGE Photograph of cave shields, Grand Palace, Lehman Caves NPS Photo Shields in the Grand Palace, Lehman Caves. Lehman Caves Management Plan Great Basin National Park Baker, Nevada June 2019 Approved by: James Woolsey, Superintendent Date Executive Summary The Lehman Caves Management Plan (LCMP) guides management for Lehman Caves, located within Great Basin National Park (GRBA). The primary goal of the Lehman Caves Management Plan is to manage the cave in a manner that will preserve and protect cave resources and processes while allowing for respectful recreation and scientific use. More specifically, the intent of this plan is to manage Lehman Caves to maintain its geological, scenic, educational, cultural, biological, hydrological, paleontological, and recreational resources in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, and current guidelines such as the Federal Cave Resource Protection Act and National Park Service Management Policies. Section 1.0 provides an introduction and background to the park and pertinent laws and regulations. Section 2.0 goes into detail of the natural and cultural history of Lehman Caves. This history includes how infrastructure was built up in the cave to allow visitors to enter and tour, as well as visitation numbers from the 1920s to present. Section 3.0 states the management direction and objectives for Lehman Caves. Section 4.0 covers how the Management Plan will meet each of the objectives in Section 3.0. -

Biochemical Divergence Between Cavernicolous and Marine

The position of crustaceans within Arthropoda - Evidence from nine molecular loci and morphology GONZALO GIRIBET', STEFAN RICHTER2, GREGORY D. EDGECOMBE3 & WARD C. WHEELER4 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary- Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology; Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. ' Friedrich-Schiller-UniversitdtJena, Instituifiir Spezielte Zoologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Jena, Germany 3Australian Museum, Sydney, NSW, Australia Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, U.S.A. ABSTRACT The monophyly of Crustacea, relationships of crustaceans to other arthropods, and internal phylogeny of Crustacea are appraised via parsimony analysis in a total evidence frame work. Data include sequences from three nuclear ribosomal genes, four nuclear coding genes, and two mitochondrial genes, together with 352 characters from external morphol ogy, internal anatomy, development, and mitochondrial gene order. Subjecting the com bined data set to 20 different parameter sets for variable gap and transversion costs, crusta ceans group with hexapods in Tetraconata across nearly all explored parameter space, and are members of a monophyletic Mandibulata across much of the parameter space. Crustacea is non-monophyletic at low indel costs, but monophyly is favored at higher indel costs, at which morphology exerts a greater influence. The most stable higher-level crusta cean groupings are Malacostraca, Branchiopoda, Branchiura + Pentastomida, and an ostracod-cirripede group. For combined data, the Thoracopoda and Maxillopoda concepts are unsupported, and Entomostraca is only retrieved under parameter sets of low congruence. Most of the current disagreement over deep divisions in Arthropoda (e.g., Mandibulata versus Paradoxopoda or Cormogonida versus Chelicerata) can be viewed as uncertainty regarding the position of the root in the arthropod cladogram rather than as fundamental topological disagreement as supported in earlier studies (e.g., Schizoramia versus Mandibulata or Atelocerata versus Tetraconata). -

Impact of Agricultural Practices on Biodiversity of Soil Invertebrates

Impact of Agricultural Practices on Biodiversity of Soil Invertebrates Impact of • Stefano Bocchi and Francesca Orlando Agricultural Practices on Biodiversity of Soil Invertebrates Edited by Stefano Bocchi and Francesca Orlando Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Agronomy www.mdpi.com/journal/agronomy Impact of Agricultural Practices on Biodiversity of Soil Invertebrates Impact of Agricultural Practices on Biodiversity of Soil Invertebrates Editors Stefano Bocchi Francesca Orlando MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editors Stefano Bocchi Francesca Orlando University of Milan University of Milan Italy Italy Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Agronomy (ISSN 2073-4395) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/agronomy/special issues/Soil Invertebrates). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03943-719-1 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03943-720-7 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Valentina Vaglia. c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

Diversity of Entomopathogens Fungi: Which Groups Conquered the Insect

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/003756; this version posted April 14, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Diversity of entomopathogens Fungi: Which groups conquered the insect body? João P. M. Araújoa & David P. Hughesb aDepartment of Biology, Penn State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America. bDepartment of Entomology and Department of Biology, Penn State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America. [email protected]; [email protected]; ! Abstract The entomopathogenic Fungi comprise a wide range of ecologically diverse species. This group of parasites can be found distributed among all fungal phyla and as well as among the ecologically similar but phylogenetically distinct Oomycetes or water molds, that belong to a different kingdom (Stramenopila). As a group, the entomopathogenic fungi and water molds parasitize a wide range of insect hosts from aquatic larvae in streams to adult insects of high canopy tropical forests. Their hosts are spread among 18 orders of insects, in all developmental stages such as: eggs, larvae, pupae, nymphs and adults exhibiting completely different ecologies. Such assortment of niches has resulted in these parasites evolving a considerable morphological diversity, resulting in enormous biodiversity, much of which remains unknown. Here we gather together a huge amount of records of these entomopathogens to comparing and describe both their morphologies and ecological traits. These findings highlight a wide range of adaptations that evolved following the evolutionary transition to infecting the most diverse and widespread animals on Earth, the insects. -

Diversity of Entomopathogens Fungi: Which Groups Conquered

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/003756; this version posted April 4, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Diversity of entomopathogens Fungi: Which groups conquered the insect body? João P. M. Araújoa & David P. Hughesb aDepartment of Biology, Penn State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America. bDepartment of Entomology and Department of Biology, Penn State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America. [email protected]; [email protected]; Abstract The entomopathogenic Fungi comprise a wide range of ecologically diverse species. This group of parasites can be found distributed among all fungal phyla and as well as among the ecologically similar but phylogenetically distinct Oomycetes or water molds, that belong to a different kingdom (Stramenopila). As a group, the entomopathogenic fungi and water molds parasitize a wide range of insect hosts from aquatic larvae in streams to adult insects of high canopy tropical forests. Their hosts are spread among 18 orders of insects, in all developmental stages such as: eggs, larvae, pupae, nymphs and adults exhibiting completely different ecologies. Such assortment of niches has resulted in these parasites evolving a considerable morphological diversity, resulting in enormous biodiversity, much of which remains unknown. Here we gather together a huge amount of records of these entomopathogens to comparing and describe both their morphologies and ecological traits. These findings highlight a wide range of adaptations that evolved following the evolutionary transition to infecting the most diverse and widespread animals on Earth, the insects. -

The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231610049 The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes Article in Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology · September 2012 DOI: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 961 2,825 25 authors, including: Sina M Adl Alastair Simpson University of Saskatchewan Dalhousie University 118 PUBLICATIONS 8,522 CITATIONS 264 PUBLICATIONS 10,739 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Christopher E Lane David Bass University of Rhode Island Natural History Museum, London 82 PUBLICATIONS 6,233 CITATIONS 464 PUBLICATIONS 7,765 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Biodiversity and ecology of soil taste amoeba View project Predator control of diversity View project All content following this page was uploaded by Smirnov Alexey on 25 October 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Journal of Published by the International Society of Eukaryotic Microbiology Protistologists J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 59(5), 2012 pp. 429–493 © 2012 The Author(s) Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology © 2012 International Society of Protistologists DOI: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes SINA M. ADL,a,b ALASTAIR G. B. SIMPSON,b CHRISTOPHER E. LANE,c JULIUS LUKESˇ,d DAVID BASS,e SAMUEL S. BOWSER,f MATTHEW W. BROWN,g FABIEN BURKI,h MICAH DUNTHORN,i VLADIMIR HAMPL,j AARON HEISS,b MONA HOPPENRATH,k ENRIQUE LARA,l LINE LE GALL,m DENIS H. LYNN,n,1 HILARY MCMANUS,o EDWARD A. D. -

ÖDÖN TÖMÖSVÁRY (1852-1884), PIONEER of HUNGARIAN MYRIAPODOLOGY Zoltán Korsós Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural

miriapod report 20/1/04 10:04 am Page 78 BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MYRIAPOD AND ISOPOD GROUP Volume 19 2003 ÖDÖN TÖMÖSVÁRY (1852-1884), PIONEER OF HUNGARIAN MYRIAPODOLOGY Zoltán Korsós Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Baross u. 13, H-1088 Budapest, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Ödön (=Edmund) Tömösváry (1852-1884) immortalised his name in the science of myriapodology by discovering the peculiar sensory organs of the myriapods. He first described these organs in 1883 on selected species of Chilopoda, Diplopoda and Pauropoda. On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Tömösváry’s birth, his unfortunately short though productive scientific career is overviewed, in this paper only from the myriapodological point of view. A list of the 32 new species and two new genera described by him are given and commented, together with a detailed bibliography of Tömösváry’s 24 myriapodological works and subsequent papers dealing with his taxa. INTRODUCTION Ödön Tömösváry is certainly one of the Hungarian zoologists (if not the only one) whose name is well- known worldwide. This is due to the discovery of a peculiar sensory organ which was later named after him, and it is called Tömösváry’s organ uniformly in almost all languages (French: organ de Tömösváry, German: Tömösvárysche Organ, Danish: Tömösvarys organ, Italian: organo di Tömösváry, Czech: Tömösváryho organ and Hungarian: Tömösváry-féle szerv). The organ itself is believed to be a sensory organ with some kind of chemical or olfactory function (Hopkin & Read 1992). However, although its structure was studied in many respects (Bedini & Mirolli 1967, Haupt 1971, 1973, 1979, Hennings 1904, 1906, Tichy 1972, 1973, Figures 4-6), the physiological background is still not clear today. -

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List Associated Tables The Texas Priority Species List……………..733 Introduction For many years the management and conservation of wildlife species has focused on the individual animal or population of interest. Many times, directing research and conservation plans toward individual species also benefits incidental species; sometimes entire ecosystems. Unfortunately, there are times when highly focused research and conservation of particular species can also harm peripheral species and their habitats. Management that is focused on entire habitats or communities would decrease the possibility of harming those incidental species or their habitats. A holistic management approach would potentially allow species within a community to take care of themselves (Savory 1988); however, the study of particular species of concern is still necessary due to the smaller scale at which individuals are studied. Until we understand all of the parts that make up the whole can we then focus more on the habitat management approach to conservation. Species Conservation In terms of species diversity, Texas is considered the second most diverse state in the Union. Texas has the highest number of bird and reptile taxon and is second in number of plants and mammals in the United States (NatureServe 2002). There have been over 600 species of bird that have been identified within the borders of Texas and 184 known species of mammal, including marine species that inhabit Texas’ coastal waters (Schmidly 2004). It is estimated that approximately 29,000 species of insect in Texas take up residence in every conceivable habitat, including rocky outcroppings, pitcher plant bogs, and on individual species of plants (Riley in publication). -

The Classification of Lower Organisms

The Classification of Lower Organisms Ernst Hkinrich Haickei, in 1874 From Rolschc (1906). By permission of Macrae Smith Company. C f3 The Classification of LOWER ORGANISMS By HERBERT FAULKNER COPELAND \ PACIFIC ^.,^,kfi^..^ BOOKS PALO ALTO, CALIFORNIA Copyright 1956 by Herbert F. Copeland Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 56-7944 Published by PACIFIC BOOKS Palo Alto, California Printed and bound in the United States of America CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Introduction 1 II. An Essay on Nomenclature 6 III. Kingdom Mychota 12 Phylum Archezoa 17 Class 1. Schizophyta 18 Order 1. Schizosporea 18 Order 2. Actinomycetalea 24 Order 3. Caulobacterialea 25 Class 2. Myxoschizomycetes 27 Order 1. Myxobactralea 27 Order 2. Spirochaetalea 28 Class 3. Archiplastidea 29 Order 1. Rhodobacteria 31 Order 2. Sphaerotilalea 33 Order 3. Coccogonea 33 Order 4. Gloiophycea 33 IV. Kingdom Protoctista 37 V. Phylum Rhodophyta 40 Class 1. Bangialea 41 Order Bangiacea 41 Class 2. Heterocarpea 44 Order 1. Cryptospermea 47 Order 2. Sphaerococcoidea 47 Order 3. Gelidialea 49 Order 4. Furccllariea 50 Order 5. Coeloblastea 51 Order 6. Floridea 51 VI. Phylum Phaeophyta 53 Class 1. Heterokonta 55 Order 1. Ochromonadalea 57 Order 2. Silicoflagellata 61 Order 3. Vaucheriacea 63 Order 4. Choanoflagellata 67 Order 5. Hyphochytrialea 69 Class 2. Bacillariacea 69 Order 1. Disciformia 73 Order 2. Diatomea 74 Class 3. Oomycetes 76 Order 1. Saprolegnina 77 Order 2. Peronosporina 80 Order 3. Lagenidialea 81 Class 4. Melanophycea 82 Order 1 . Phaeozoosporea 86 Order 2. Sphacelarialea 86 Order 3. Dictyotea 86 Order 4. Sporochnoidea 87 V ly Chapter Page Orders. Cutlerialea 88 Order 6. -

Biodiversity from Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats of Georgia, USA

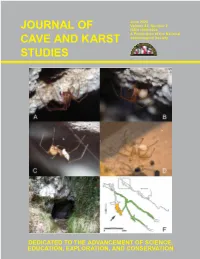

Kirk S. Zigler, Matthew L. Niemiller, Charles D.R. Stephen, Breanne N. Ayala, Marc A. Milne, Nicholas S. Gladstone, Annette S. Engel, John B. Jensen, Carlos D. Camp, James C. Ozier, and Alan Cressler. Biodiversity from caves and other subterranean habitats of Georgia, USA. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 82, no. 2, p. 125-167. DOI:10.4311/2019LSC0125 BIODIVERSITY FROM CAVES AND OTHER SUBTERRANEAN HABITATS OF GEORGIA, USA Kirk S. Zigler1C, Matthew L. Niemiller2, Charles D.R. Stephen3, Breanne N. Ayala1, Marc A. Milne4, Nicholas S. Gladstone5, Annette S. Engel6, John B. Jensen7, Carlos D. Camp8, James C. Ozier9, and Alan Cressler10 Abstract We provide an annotated checklist of species recorded from caves and other subterranean habitats in the state of Georgia, USA. We report 281 species (228 invertebrates and 53 vertebrates), including 51 troglobionts (cave-obligate species), from more than 150 sites (caves, springs, and wells). Endemism is high; of the troglobionts, 17 (33 % of those known from the state) are endemic to Georgia and seven (14 %) are known from a single cave. We identified three biogeographic clusters of troglobionts. Two clusters are located in the northwestern part of the state, west of Lookout Mountain in Lookout Valley and east of Lookout Mountain in the Valley and Ridge. In addition, there is a group of tro- globionts found only in the southwestern corner of the state and associated with the Upper Floridan Aquifer. At least two dozen potentially undescribed species have been collected from caves; clarifying the taxonomic status of these organisms would improve our understanding of cave biodiversity in the state. -

Phylogenomics Illuminates the Backbone of the Myriapoda Tree of Life and Reconciles Morphological and Molecular Phylogenies

Phylogenomics illuminates the backbone of the Myriapoda Tree of Life and reconciles morphological and molecular phylogenies The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Fernández, R., Edgecombe, G.D. & Giribet, G. Phylogenomics illuminates the backbone of the Myriapoda Tree of Life and reconciles morphological and molecular phylogenies. Sci Rep 8, 83 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18562-w Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37366624 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Title: Phylogenomics illuminates the backbone of the Myriapoda Tree of Life and reconciles morphological and molecular phylogenies Rosa Fernández1,2*, Gregory D. Edgecombe3 and Gonzalo Giribet1 1 Museum of Comparative Zoology & Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 28 Oxford St., 02138 Cambridge MA, USA 2 Current address: Bioinformatics & Genomics, Centre for Genomic Regulation, Carrer del Dr. Aiguader 88, 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3 Department of Earth Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] The interrelationships of the four classes of Myriapoda have been an unresolved question in arthropod phylogenetics and an example of conflict between morphology and molecules. Morphology and development provide compelling support for Diplopoda (millipedes) and Pauropoda being closest relatives, and moderate support for Symphyla being more closely related to the diplopod-pauropod group than any of them are to Chilopoda (centipedes). -

Journal of Cave and Karst Studies

June 2020 Volume 82, Number 2 JOURNAL OF ISSN 1090-6924 A Publication of the National CAVE AND KARST Speleological Society STUDIES DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE, EDUCATION, EXPLORATION, AND CONSERVATION Published By BOARD OF EDITORS The National Speleological Society Anthropology George Crothers http://caves.org/pub/journal University of Kentucky Lexington, KY Office [email protected] 6001 Pulaski Pike NW Huntsville, AL 35810 USA Conservation-Life Sciences Julian J. Lewis & Salisa L. Lewis Tel:256-852-1300 Lewis & Associates, LLC. [email protected] Borden, IN [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Earth Sciences Benjamin Schwartz Malcolm S. Field Texas State University National Center of Environmental San Marcos, TX Assessment (8623P) [email protected] Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Leslie A. North 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, KY Washington, DC 20460-0001 [email protected] 703-347-8601 Voice 703-347-8692 Fax [email protected] Mario Parise University Aldo Moro Production Editor Bari, Italy [email protected] Scott A. Engel Knoxville, TN Carol Wicks 225-281-3914 Louisiana State University [email protected] Baton Rouge, LA [email protected] Exploration Paul Burger National Park Service Eagle River, Alaska [email protected] Microbiology Kathleen H. Lavoie State University of New York Plattsburgh, NY [email protected] Paleontology Greg McDonald National Park Service Fort Collins, CO The Journal of Cave and Karst Studies , ISSN 1090-6924, CPM [email protected] Number #40065056, is a multi-disciplinary, refereed journal pub- lished four times a year by the National Speleological Society.