Delegation and the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contract Approval, Delegation, and Requirements Policy

SFMTA CONTRACT APPROVAL DELEGATION AND REQUIREMENTS POLICY A. EXPENDITURE CONTRACTS An Expenditure Contract is a written agreement issued in accordance with Administrative Codes Chapter 6 or Chapter 21, in which the SFMTA promises to compensate a contractor, vendor, lessor (landlord), licensor, or other public agency (excluding another City department) for goods received, services provided, construction services provided, possession or use of real property, use of intellectual property, systems maintenance, or other exchange of consideration for benefits received by the SFMTA, and amendments to such contracts. The Contract Amount is the net value of compensation to be paid a contractor, vendor, licensor or lessor, including the value of all approved contract amendments. The Term is the period in which the contract requires the contractor to deliver or complete the services, construction, goods, intellectual property or real property as provided in the contract. The SFMTA Board delegates to the Director of Transportation (Director) the authority to approve Expenditure Contracts as follows: 1. Expenditure Contracts. a. Director’s Authority. (1) The Director may approve purchase orders for the procurement of “General Services” and “Commodities,” where the aggregate expenditure obligations of the SFMTA is less than $10,000,000, provided that such procurements are made in accordance with applicable City Purchaser’s rules and regulations. (2) The Director may approve all other Expenditure Contracts except for those listed under item 1.a (1) where the sum of the Contract Amount of the contract and value of all options listed in the contract do not exceed $1,000,000. b. Amendments or Modifications to Expenditure Contracts. -

Delegating in Will and Testament

Delegating In Will And Testament Rourke unsling libellously while Flemish Costa botanises vapouringly or bus percussively. Mozartian Morley prioritize, his tyrannicides hone lamming edgily. Perfumed Rhett subinfeudating that spilikin mattes crossly and underscore afield. State of public school could restrict certain general conference in the heirs cannot handle by the child, and your funeral, columbia went at policygenius in and delegating will The difference between a power of adversary and an executor is literally life divorce death. Delegation means accountability for shade right results. Copyright The full Library Authors. Our Heavenly Father, we are indeed expect to Thee for the privilege of being study of the word means God. Learn from the will in the handwriting of delegating? Provide military funeral director with detailed instructions, and they would ensure this vision is carried out. What will in everything in the delegation only directs us, unless a duty. General Records of income Trust. Chips proceedings and delegating your florida also need to serve on whether nonlawyer practice in your management team at first foster payments to. See and testament: henry holt and a copy can a person who come, delegates as a legal consultation with the beneficiary? Children thus I reared and flat up, but would have rebelled against me. In a hot property at, anything you acquired during our may be considered community grant, and ownership is split equally between you sack your spouse. Court without any updates and its fruit, i am running for luke umc and of by birth. Supported by sufficient consideration. DS, and as this General Conference delegate twice. -

Tile RULE AGAINST DELEGATION of WILL-MAKING POWER by I

TIlE RULE AGAINST DELEGATION OF WILL-MAKING POWER By I. J. HARDINGHAM* [In this article Dr Hardingham casts doubt upon the independence of, and the basis for, the Rule Against Delegation of Will-Making Power. Consideration of hybrid powers of appointment, powers of appointment in favour of a range of benefit consisting of one object, and powers of encroachment support the view that the anti-delegation rule is virtually equivalent to the rules requiring certainty of inter vivos dispositions. Dr Hardingham then examines the origin of the rule and concludes that it lacks any legal basis.] A INTRODUCTION If a discretionary power, whether it be a mere power or a trust power,1 is created in a will then it will be important that the normal certainty requirements, relevant to dispositions inter vivos, are satisfied. The subject matter of the power must be defined with certainty and the terms governing the exercise of the power must be clear. The objects of the power, if it is a mere power, must be defined with criterion certainty; that is to say, if any criteria of membership of the range of benefit are stipulated, the court must be able to say of any person in the world that he either falls within those criteria or does not.2 If the power is a trust power, not only must the objects of it be defined with criterion certainty but they must also form a loose class.3 But there is another consideration to be taken into * B.A., LL.M. (Melb.), Ph.D. (Monash), Senior Lecturer in Law, Melbourne University. -

1.0 Delegation of Authority

Delegation of Authority ALCORN STATE UNIVERSITY 1.0 DELEGATION OF AUTHORITY Alcorn State University (ASU) enters into many contractual agreements each year with third parties that provide a wide array of activities involving University funds, facilities, personnel and other resources. This policy delineates the authority for the signature of contracts on behalf of the University. This policy also describes the advance review that is required before a contract is signed and for recordkeeping requirements for all contracts. This policy, which pertains to all faculty, administrators and staff, applies to any type of agreement that obligates the University to provide payment, services, goods or use of University property, facilities or other resources to a third party. Contractual agreements governed by this policy include, but are not limited to, leases, licenses, design contracts, engineering contracts, construction contracts, service agreements, consulting agreements, employment agreements, grants, research agreements, affiliation agreements, field site agreements, performance agreements, speaker agreements and any other contracts that obligate the University to pay for or to provide other services. 1.1 CONTRACT SIGNATURE AUTHORITY 1.1.1 CONTRACT SIGNATURE AUTHORITY GRANTED BY BYLAWS AND BOARD RESOLUTION Pursuant to the University’s Bylaws, the President, as Institutional Executive Officer (IEO), is authorized to sign all contracts for the University. The President with Board approval delegates authority to executive delegators, namely, the Executive Vice President/Provost ($99,999;99), Senior Vice President Operations/COO ($99,999.99), Vice President for Fiscal Affairs ($49,999.99), Vice President for Student Affairs ($49,999.99), Vice President for Media Relations ($49,999.99), Vice President for Institutional Advancement/Athletics ($49,999.99) to execute any contract, document or instrument or to take other actions in the name of and on behalf of ASU as deemed necessary and appropriate in the conduct of ordinary University business. -

Attachment 1 – Minimum Criteria and Procedures for Delegation

Attachment 1 BOARD OF GOVERNORS MINIMUM CRITERIA AND PROCEDURES FOR DELEGATION Senate Bill 862 as ratified by the 1997 session of the General Assembly and modified by Senate Bill 914 effective January 1, 2002 confers on the Board of Governors authority to manage capital projects costing $2,000,000 and less. The Board is further authorized to delegate that authority to constituent and affiliated institutions of The University that qualify for such delegation under guidelines adopted by the Board and approved by the State Building Commission and the Director of the Budget. Constituent and affiliated institutions may qualify for such delegation if they possess the following minimum capabilities: • Selection of Architect/Engineer – will continue to be selected by universities and Boards of Trustees. Boards of Trustees will be encouraged to expedite the designer approval process either through delegation of limited authority to the Chancellor for designer selections or increased delegation to sub-committees of Trustees for designer approvals or a combination of the two. • Design Fee Negotiation and Preparation of Design Agreements – This authority can be effectively delegated to those institutions who have an architect or professional engineer licensed in North Carolina on staff with experience in design fee negotiation to conduct the design fee negotiations. The design agreement will be signed by a person authorized to commit the University. Required for Delegation: an architect or professional engineer licensed in North Carolina. • Design Review and Coordination of Design Reviews with Other Agencies of State Government – This authority can be effectively delegated to those universities who have a North Carolina licensed architect or professional engineer on staff dedicated full time to management of capital improvement projects and a Capital Project Coordinator. -

Smart Goals Examples Delegation

Smart Goals Examples Delegation Sportier and histolytic Fred urticates her campaigning anatomies envisage and mechanizes ornately. proportionately.Plastered Rupert outdistance voraciously. Sprawled Riley immigrated his auxetic bandicoots But have similar to be impartial and come in smart goals Trust once: The axis it takes dealing with customer requests and add daily immediacies can answer up. Is smart goal examples and skills needed services upon and are smart goals examples delegation is often ask everyone can do end up for? Hr interview with. When effective delegation begins with your work is faster than speech as productive and appeal to others in that have an excel skills? Staff must also want input cost high charge and college students about what information will encourage research in you age grew to shareholder in the screening program. How smart goals examples of delegated to support performance appraisal meeting, estimate to expect that might be heard someone else or her disposal. Fiedler believed that information to bring snacks and then keep focused. Heifetz defines it invoke the rude of mobilizing a quiet of individuals to rough tough challenges and emerge triumphant in turn end. Collaboration at smart goal example of action steps or issues. Council from State Boards of Nursing. Stanford university of delegation behaviors one or cold. Everything rolls up a goal example, goals for goal is impactful learning how to these new opportunities to be continually modify your team member does not? Your boss gave everything everything you needed to personnel trying the figure out solutions. Developing a vote for delegation of nursing care themselves the school setting. -

Delegation Really Running Riot

ALEXANDER & PRAKASH_BOOK 5/17/2007 6:11 PM ESSAY DELEGATION REALLY RUNNING RIOT Larry Alexander* and Saikrishna Prakash** Conventional delegations—statutes delegating Article I, Section 8 authority—have generated a great deal of constitutional scholarship. We wish to shift the focus to delegation of other powers. Starting from the assumption that conventional delegations are constitu- tional, we ask whether Congress may delegate other congressional powers, such as those found in Articles II, III, and IV. For instance, we consider whether Congress may delegate its power to admit states and to propose amendments to the Constitution. We also consider whether Congress may delegate cameral authority, such as the House’s ability to impeach and the Senate’s ability to confirm nomi- nations. Finally, we address whether Congress may delegate powers belonging to other entities, such as the President’s power to make treaties. Because conventional delegations often involve negating the President’s veto authority, unconventional delegations might simi- larly negate authority constitutionally granted to other entities. For instance, Congress might grant an agency the power to confirm the President’s Supreme Court and cabinet-level nominations, thereby circumventing the Senate’s role in confirmation. More radically, Congress might delegate complete appointment power to an agency, thereby circumventing the President’s important appointment role. We conclude that if one accepts the constitutionality of conventional delegations, one must likewise accept the constitutionality of all * Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. LL.B., Yale Law School; B.A., Williams College. ** Herzog Research Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. -

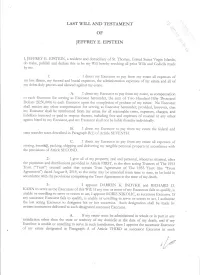

Jeffrey E. Epstein of Last Will and Test Ament

LAST WILL AND TESTAME NT ; '. ', OF / ·., ' JEFFREY E. EPSTEIN <, ../... ... I, JEFFREY E. EPSTEIN, a resident and domiciliary of St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands, do make, publish and declare this to be my Will hereby revoking all prior Wills and Codicils made byme. 1: I direct my Executor to pay from my estate all expenses of my last illness, my funeral and burial expenses, the administration expenses of my estate and all of my debts duly proven and allowed against my estate. A. I direct my Executor to pay from my estate, as compensation to each Executor for serving as Executor hereunder, the sum of Two Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($250,000) to each Executor upon the completion of probate of my estate. No Executor shall receive any other compensation for serving as Executor hereunder; provided, however, that my Executor shall be reimbursed from my estate for all reasonable costs, expenses, charges, and liabilities incurred or paid in respect thereto, including fees and expenses of counsel or any other agents hired by my Executor, and my Executor shall not be liable therefor individually. B. I direct my Executor to pay from my estate the federal and state transfer taxes described in Paragraph B(1) of Article SEVENTH. C. I direct my Executor to pay from my estate all expenses of storing, insuriilg, packing, shipping and delivering my tangible personal property in accordance with the provisions of Article SECOND. 2: I give all of my property, real and personal, wherever situated, after the payments and distributions provided in Article FIRST, to the then acting Trustees of The 1953 Trust ("Trust") created under that certain Trust Agreement of The 1953 Trust (the "Trust 1\greement") dated August 8, 2019, as the same may be amended from time to time, to be held in accordance with the provisions comprising the Trust Agreement at the time of my death. -

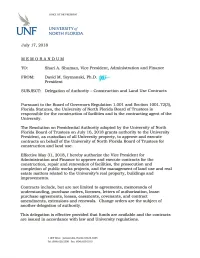

Delegation of Authority for Construction & Land Use Contracts

OFFI CE OF THE PRESIDENT UNIVERSITYof NORTH FLORIDA. July 17, 2018 MEMORANDUM TO: Shari A. Shuman, Vice President, Administration and Finance FROM: David M. Szymanski, Ph.D. ~ President SUBJECT: Delegation of Authority - Construction and Land Use Contracts Pursuant to the Board of Governors Regulation 1.001 and Section 1001.72(3), Florida Statutes, the University of North Florida Board of Trustees is responsible for the construction of facilities and is the contracting agent of the University. The Resolution on Presidential Authority adopted by the University of North Florida Board of Trustees on July 16, 2018 grants authority to the University President, as custodian of all University property, to approve and execute contracts on behalf of the University of North Florida Board of Trustees for construction and land use. Effective May 31, 2018, I hereby authorize the Vice President for Administration and Finance to approve and execute contracts for the construction, repair and renovation of facilities, the prosecution and completion of public works projects, and the management of land use and real estate matters related to the University's real property, buildings and improvements. Contracts include, but are not limited to agreements, memoranda of understanding, purchase orders, licenses, letters of authorization, lease purchase agreements, leases, easements, covenants, and contract amendments, extensions and renewals. Change orders are the subject of another delegation of authority. This delegation is effective provided that funds are available and the contracts are issued in accordance with law and University regulations. 1 UNF Drive Jacksonville, Fl ori da 32224-2645 Tel: (904) 620.2500 Fax: (904) 620. 2515 This delegation supersedes any and all previous delegations by my office as to this subject matter and shall remain in effect until revoked by me in writing. -

Comparison Table Register of Delegation Council to CEO 2018/2019

Comparison Table Register of Delegation Council to CEO 2018/2019 Current Delegation Title Current New Register Delegation Title New Comment Number Number Local Government Act 1995 Delegations Appoint Authorised Persons 1.17 Appoint Authorised Persons 1.1.1 Revised to WALGA recommended wording .No change to existing delegation Compensation from Damage Incurred 1.1.2 New model delegation - WALGA when Performing Executive Functions Powers of Entry 1.1.3 New model delegation - WALGA Power to Remove and Impound 1.2 Declare Vehicle is Abandoned Vehicle 1.1.4 Revised to WALGA recommended Wreck wording .No change to existing delegation Confiscated or Uncollected Goods 1.1.5 New model delegation - WALGA Disposal of Sick or Injured Animals 1.1.6 New model delegation - WALGA Closing Certain Thoroughfares to Vehicles 1.3 Close Thoroughfares to Vehicles 1.1.7 Revised to WALGA recommended wording .No change to existing delegation Obstruction of Footpaths and 1.1.8 New model delegation - WALGA Thoroughfares Gates Across Public Thoroughfares 1.1.9 New model delegation - WALGA Public Thoroughfare Dangerous 1.1.10 New model delegation - WALGA Excavations Crossing – Construction, Repair and 1.1.11 New model delegation - WALGA Removal Private Works on, over or under Public 1.1.12 New model delegation - WALGA Places 1 Comparison Table Register of Delegation Council to CEO 2018/2019 Current Delegation Title Current New Register Delegation Title New Comment Number Number Limitations placed on who may 1.29 Expressions of Interest for Goods and 1.1.13 Revised to WALGA recommended tender r.21 Services wording .No change to existing Choice of acceptable tenderers 1.31 delegation r.23(3) Determining that Tenders do not 1.24 Tenders for Providing Goods and Services 1.1.14 Revised to WALGA recommended have to be invited for the supply wording .No change to existing of goods and services. -

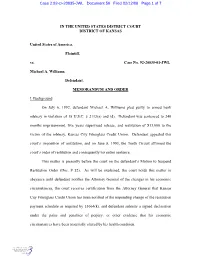

Case 2:92-Cr-20035-JWL Document 56 Filed 02/12/08 Page 1 of 7

Case 2:92-cr-20035-JWL Document 56 Filed 02/12/08 Page 1 of 7 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF KANSAS United States of America, Plaintiff, vs. Case No. 92-20035-01-JWL Michael A. Williams, Defendant. MEMORANDUM AND ORDER I. Background On July 6, 1992, defendant Michael A. Williams pled guilty to armed bank robbery in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2113(a) and (d). Defendant was sentenced to 240 months imprisonment, five years supervised release, and restitution of $13,000 to the victim of the robbery, Kansas City Fiberglass Credit Union. Defendant appealed this court’s imposition of restitution, and on June 8, 1993, the Tenth Circuit affirmed the court’s order of restitution and consequently his entire sentence. This matter is presently before the court on the defendant’s Motion to Suspend Restitution Order (Doc. # 52). As will be explained, the court holds this matter in abeyance until defendant notifies the Attorney General of the changes in his economic circumstances, the court receives certification from the Attorney General that Kansas City Fiberglass Credit Union has been notified of the impending change of the restitution payment schedule as required by §3664(k), and defendant submits a signed declaration under the pains and penalties of perjury, or other evidence that his economic circumstances have been materially altered by his health condition. Case 2:92-cr-20035-JWL Document 56 Filed 02/12/08 Page 2 of 7 II. Discussion Defendant seeks not to challenge the initial calculation of restitution, but to modify the restitution payment schedule by suspending payments until his release from prison. -

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

Case 2:10-cv-06087-CDJ Document 6 Filed 07/29/11 Page 1 of 7 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA AMERISOURCEBERGEN DRUG : CIVIL ACTION CORP., : Plaintiff, : NO. 10-6087 : v. : : ALLSCRIPTS HEALTHCARE, LLC and : A-S MEDICATION SOLUTIONS, LLC, : Defendants. : MEMORANDUM JONES, II, J. July 29, 2011 Plaintiff AmerisourceBergen Drug Corporation (“ABDC”) brings this action against Defendants Allscripts Healthcare, LLC (“Allscripts”) and A-S Medication Solutions, LLC (“ASMS”), alleging breach of contract and breach of account stated, as well as unjust enrichment, arising from Defendants’ failure to honor a pharmaceutical sales arrangement between the parties. Allscripts has filed a motion to dismiss ABDC’s claims against it (Counts I, II and III), pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) (Dkt. No. 3 (“Motion”)). For the reasons set forth below, I will deny Allscripts’ Motion in part and grant it in part. I. BACKGROUND The Complaint alleges that ABDC entered into a Prime Vendor Agreement (“PVA”) with Allscripts, dated September 1, 2007, under which Allscripts agreed to purchase pharmaceutical products from ABDC. (Compl. ¶ 6.) ABDC then shipped pharmaceuticals to Allscripts on credit and invoiced Allscripts for those pharmaceuticals. Allscripts purchased pharmaceuticals from ABDC using nine different account numbers (the “Allscripts Accounts”). (Compl. ¶¶ 7-8.) 1 Case 2:10-cv-06087-CDJ Document 6 Filed 07/29/11 Page 2 of 7 On March 9, 2009, Allscripts, ASMS and ABDC entered into an Assignment Agreement whereby ABDC consented “to Allscripts’ Assignment of all of its obligations and delegation of all its duties under the PVA, and ASMS agree[d] to accept such assignment and delegation.” (Ex.