Troublous Times in New Mexico, 1659–1670

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Middle Rio Grande Basin: Historical Descriptions and Reconstruction

CHAPTER 4 THE MIDDLE RIO GRANDE BASIN: HISTORICAL DESCRIPTIONS AND RECONSTRUCTION This chapter provides an overview of the historical con- The main two basins are flanked by fault-block moun- ditions of the Middle Rio Grande Basin, with emphasis tains, such as the Sandias (Fig. 40), or volcanic uplifts, on the main stem of the river and its major tributaries in such as the Jemez, volcanic flow fields, and gravelly high the study region, including the Santa Fe River, Galisteo terraces of the ancestral Rio Grande, which began to flow Creek, Jemez River, Las Huertas Creek, Rio Puerco, and about 5 million years ago. Besides the mountains, other Rio Salado (Fig. 40). A general reconstruction of hydro- upland landforms include plateaus, mesas, canyons, pied- logical and geomorphological conditions of the Rio monts (regionally known as bajadas), volcanic plugs or Grande and major tributaries, based primarily on first- necks, and calderas (Hawley 1986: 23–26). Major rocks in hand, historical descriptions, is presented. More detailed these uplands include Precambrian granites; Paleozoic data on the historic hydrology-geomorphology of the Rio limestones, sandstones, and shales; and Cenozoic basalts. Grande and major tributaries are presented in Chapter 5. The rift has filled primarily with alluvial and fluvial sedi- Historic plant communities, and their dominant spe- ments weathered from rock formations along the main cies, are also discussed. Fauna present in the late prehis- and tributary watersheds. Much more recently, aeolian toric and historic periods is documented by archeological materials from abused land surfaces have been and are remains of bones from archeological sites, images of being deposited on the floodplain of the river. -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

Church Trends in Latin America

A PROLADES Study, Reflection & Discussion Document DRAFT COPY - NOT FOR PUBLICATION Church Trends in Latin America Compiled and Edited by Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES Last revised on 21 December 2012 Produced by PROLADES Apartado 1525-2050, San Pedro, Costa Rica Telephone: 506-2283-8300; FAX 506-234-7682 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.prolades.com 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Defining the “full breadth of Christianity in Latin America” I. A General Overview of Religious Affiliation in Latin America and the Caribbean by Regions and Countries, 2010………………………………………………………………….. 5 II. The Western Catholic Liturgical Tradition……………………………………………………. 10 A. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………... 10 B. The period of Roman Catholic hegemony in Latin America, 1500-1900…………………………. 18 (1) The Holy Office of the Inquisition in the Americas…………………………………………… 18 (2) Religious Liberty in Latin America after Independence………………………………………. 26 (3) Concordats……………………………………………………………………………………. 32 C. The period of accelerated religious change in Latin America, 1800 to date……………………… 36 D. Defections from the Roman Catholic Church in Latin America since 1950; the changing religious marketplace………………………………………………………………... 41 (1) Defections to Protestantism…………………………………………………………………… 42 (2) Defections to Marginal Christian groups……………………………………………………... 60 (3) Defections to independent Western Catholic movements…………………………………….. 60 (4) Defections to non-Christian religions………………………………………………………… 61 (5) Defections to secular society (those with no -

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

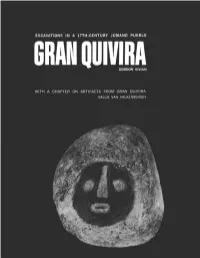

Gran Quiviragordon Vivian

EXCAVATIONS I N A 17TH-CENTURY JUMANO PUEBLO GRAN QUIVIRA GORDON VIVIAN WITH A CHAPTER ON ARTIFACTS FROM GRAN QUlVlRA SALLIE VAN VALKENBURGH ARCHEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER EIGHT NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE George B. Hartzog, Jr., Director America's Natural Resources Created in 1849, the Department of the Interior–America's Department of Natural Resources– is concerned with the management, conservation, and de- velopment of the Nation's water, wildlife, mineral, forest, and park and recre- ational resources. It also has major responsibilities for Indian and territorial affairs. As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Departmentworks to as- sure that nonrenewable resources are developed and used wisely, that park and recreational resources are conserved, and that renewable resources make their full contribution to the progress, prosperity, and security of the United States- now and in the future. Archeological Research Series No. 1. Archeology of the Bynum Mounds, Mississippi. No. 2. Archeological Excavations in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1950. No. 3. Archeology of the Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia. No. 4. Archeological Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia. No. 5. The Hubbard Site and Other Tri-wall Structures in New Mexico and Colorado. No. 6. Search for the Cittie of Ralegh, Archeological Excavations at Fort Ralegh National Historic Site, North Carolina. No. 7. The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. No. 8. Excavations in a 17th-century Jumano Pueblo, Gran Quivira, New Mexico. THIS PUBLICATION is one of a series of research studies devoted to specialized topics which have been explored in connection with the various areas in the National Park System. -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

CHAPTER 3 HUMAN SETTLEMENT PATTERNS, POPULATIONS, AND RESOURCE USE This chapter presents an overview, in three main sec- reasoning, judgment, and his ideas of enjoyment, tions, of the ways in which each of the three major eco- as well as his education and government (Hughes cultures of the area has adapted to the various ecosys- 1983: 9). tems of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. These groups consist of the American Indians, Hispanos, and Anglo-Americans. This philosophy permeated all aspects of traditional Within the American Indian grouping, four specific Pueblo life; ecology was not a separate attitude toward groups—the Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, and Ute—are dis- life but was interrelated with everything else in life. cussed in the context of their interactions with the environ- Another perspective on Native Americans was given by ment (Fig. 15). The Hispanic population is discussed as a Vecsey and Venables (1980: 23): single group, although the population was actually com- posed of several groups, notably the Hispanos from Spain To say that Indians existed in harmony with na- or Mexico, the genizaros (Hispanicized Indians from Plains ture is a half-truth. Indians were both a part of and other regional groups), mestizos (Hispano-Indio nature and apart from nature in their own “mix”), and mulatos (Hispano-Black “mix”). Their views world view. They utilized the environment ex- and uses of the land and water were all very similar. Anglo- tensively, realized the differences between hu- Americans could also be broken into groups, such as Mor- man and nonhuman persons, and felt guilt for mon, but no such distinction is made here. -

The Religious Lives of Franciscan Missionaries, Pueblo Revolutionaries, and the Colony of Nuevo Mexico, 1539-1722 Michael P

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Among the Pueblos: The Religious Lives of Franciscan Missionaries, Pueblo Revolutionaries, and the Colony of Nuevo Mexico, 1539-1722 Michael P. Gueno Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES AMONG THE PUEBLOS: THE RELIGIOUS LIVES OF FRANCISCAN MISSIONARIES, PUEBLO REVOLUTIONARIES, AND THE COLONY OF NUEVO MEXICO, 1539-1722 By MICHAEL P. GUENO A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Michael P. Guéno defended on August 20, 2010. __________________________________ John Corrigan Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Edward Gray University Representative __________________________________ Amanda Porterfield Committee Member __________________________________ Amy Koehlinger Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ John Corrigan, Chair, Department of Religion _____________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For Shaynna iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure and honor to remember the many hands and lives to which this manuscript and I are indebted. The innumerable persons who have provided support, encouragement, and criticism along the writing process humble me. I am truly grateful for the ways that they have shaped this text and my scholarship. Archivists and librarians at several institutions provided understanding assistance and access to primary documents, especially those at the New Mexico State Record Center and Archive, the Archive of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Archivo General de la Nacion de Mexico, and Biblioteca Nacional de la Anthropologia e Historia in Mexico City. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Themes: The Original Inhabitants UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Indian Meets European NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC QUARAI AND/OR COMMON Quarai State Monument______________________________ | LOCATION STREET& NUMBER on secondary road about 1 mile west of Punta de Agua _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Punta de Agua x VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New Mexico 35 Torrance 057 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED ^AGRICULTURE ^MUSEUM — BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X-PARK —STRUCTURE j^BOTM _ WORK IN PROGRESS _ EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE *SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS ?LYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC JOBBING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION __NO —MILITARY X-OTHER 9raizing IOWNER OF PROPERTY State of New Mexico NAME (Mr. Tom Caperton> current chief of Monuments Division, Museum of New Mexico STREETS NUMBER P.O. Box 2087 CITY, TOWN STATE Santa Fe VICINITY OF New Mexico 87501 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTIONAlso; Torrance county courthouse, COURTHOUSE. Estancia, New Mexico REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC State Lands Office STREETS NUMBER P.O. Box 1148 CITY. TOWN STATE Fo New Mexico REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE -

Chronicles of the Trail

Chronicles of the Trail Quarterly Journal of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association Vol. 6, No. 1 Winter 2010 Christian Soldier with Santo Niño Moro – Bracho, Zacatecas LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 25 January 2010 Dear Readers— As promised, I want to inform the CARTA Board It is with understanding and regret that the Executive and membership about a variety of well established Committee accepted his resignation. projects. Although I can only mention a few items of We are very grateful for the amount of work that interest here, please see our “News & Notes” section Will was able to accomplish in such a short time, for more updates. particularly helping with the development of in-house With an eye toward developing El Camino Real written policies. Candidates interested in applying for spur and loop trails to the planned Rio Grande River an appointment as interim President (to serve until Trail, New Mexico State University linguistics professor the September elections) are asked to send their vita and new CARTA member Daniel Villa will conduct and a Letter of Interest to PO Box 15162, Las Cruces, a series of oral history projects. The information will NM 88004 or e-mail [email protected]. We look be used to enhance the visitor experience by adding forward to working with Will as an active member, a contemporary or “living” history component to and we wish him all the best. cultural and heritage tourism. There is also a potential The full Board has agreed to meet the weekend of cultural/heritage corridor partnership in the works 13 March 2010 (Mountainair, NM) to update and revise with Laurie Frantz, Director, NM Scenic Byways. -

Kiva, Cross, and Crown

National Park Service: Kiva, Cross, and Crown The photograph of Wahu Toya, identified by Edgar L. Hewett as "Wa-ng" and by Elsie Clews Parsons as "Francisco Kota or Waku," Table of Contents was taken at Jemez pueblo by John K. Hillers. B. M. Thomas Collection, Museum of New Mexico. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/kcc/index.htm[8/14/2012 8:55:28 AM] National Park Service: Kiva, Cross, and Crown (Table of Contents) Cover Foreword Preface I The Invaders, 1540-1542 II The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest, 1542-1595 III Oñate's Disenchantment, 1595-1617 IV The "Christianization" of Pecos, 1617-1659 V The Shadow of the Inquisition, 1659-1680 VI Their Own Worst Enemies, 1680-1704 VII Pecos and the Friars, 1704-1794 VIII Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas, 1704-1794 IX Toward Extinction, 1794-1840 Epilogue Appendices I Population II Notable Natives III The Franciscans IV Encomenderos and Alcaldes Mayores V Miera's 1758 Map of New Mexico Abbreviations Notes Bibliography Index (omitted from the online edition) Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kessell, John L. Kiva, cross, and crown. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/kcc/contents.htm[8/14/2012 8:55:32 AM] National Park Service: Kiva, Cross, and Crown (Table of Contents) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Pecos, N.M.—History. 2. New Mexico—History— To 1948. I. Title. E99.P34K47 978.9'55 77-26691 This book has subsequently been republished by the Western National Parks Association. Cover. Three panels of the cover design symbolize the story of Pecos. -

Morgan Labin Veraluz Dissertation

Deserts of Plenty, Rivers of Want: Apaches and the Inversion of the Colonial Encounter in the Chihuahuan Borderlands, 1581-1788 by Morgan LaBin Veraluz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: !Professor Philip J. Deloria, Chair !Associate Professor Anthony P. Mora !Associate Professor Michael J. Witgen !Professor Donald R. Zak © Morgan LaBin Veraluz 2014 For Tom and Lei, my parents & for Claire, my wife ii Table of Contents Dedication........................................................................................................................ii List of Maps.....................................................................................................................iv Abstract............................................................................................................................v Introduction:!The Power of Chihuahuan Borderlands; Faraon and Mescalero !!Apacherías and the Inversion of the Colonial Encounter...........................1 Chapter 1: !Discovery: Riparian Empire in the Chihuahuan Desert; Ecological !!Asymmetries around New Mexico............................................................37 Chapter 2:!Invasion: Faraon Reconquista and Spanish Interregnum !!Reinterpreted..........................................................................................104 Chapter 3:!Experimentation: Faraon Apachería during the Second Era of !!Colonial Encounter..................................................................................168 -

Reconstructing a Chicano/A Literary Heritage: Hispanic Colonial Literature of the Southwest

Reconstructing a Chicano/a Literary Heritage: Hispanic Colonial Literature of the Southwest Item Type book; text Publisher University of Arizona Press (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © 1993 by The Arizona Board of Regents. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY- NC-ND 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Download date 11/10/2021 08:08:24 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/632275 RECONSTRUCTING A CHICANO/A LITERARY HERITAGE HISPANIC COLONIAL LITERA TURE OFTHE SOUTHWEST EDITED BY MAR fA HERRERA-SOBEK Reconstructing a Chicano/a Literary Heritage Reconstructing a Chicano/a Literary Heritage Hispanic Colonial Literature of the Southwest Edited by MARIA HERRERA-SOBEK THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS Tucson This Open Arizona edition is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu Copyright © 1993 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2018 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3780-8 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Typographical errors may have been introduced in the digitization process. The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows: Reconstructing a Chicano/a literary heritage : Hispanic colonial literature of the Southwest / edited by María Herrera-Sobek.