Exploring the Differences in Development Paths Between the Dominican Republic and Haiti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dominican Republic

Required Report: Required - Public Distribution Date: June 29,2020 Report Number: DR2020-0012 Report Name: Retail Foods Country: Dominican Republic Post: Santo Domingo Report Category: Retail Foods Update on the Dominican Republic Retail Sector Prepared By: Mayra Carvajal Approved By: Elizabeth Autry Report Highlights: Report Highlights: The Dominican Republic (DR) is one of the most dynamic economies in the Caribbean region. With U.S. consumer-oriented product exports reaching US$600 million in 2019, the country represents the fifth-largest market in Latin America. The DR’s modern retail sector is growing rapidly and offers a wide variety of U.S. products. However, despite the prominence and growth of local supermarket chains, they only account for 20-25 percent of total retail sales. Most sales are still in the traditional channel, which includes neighborhood stores (colmados) and warehouses, which offer largely local products. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Market Fact Sheet: Dominican Republic Quick Facts CY 2019 List of Top 10 Growth Products The Dominican Republic (DR) is an upper middle-income country with low and stable inflation. It is the second-largest economy in 1) Cheese 6) Meat (Beef) the Caribbean, just behind Cuba, and the third-largest country in 2) Wine 7) Seafood terms of population (behind Cuba and Haiti). In 2019, the DR’s 3) Beer 8) Snack foods GDP reached approximately US$89 billion, a 5.1 percent increase 4) Pork 9) Frozen potatoes/veg from 2018. The DR’s major export growth has shifted away from 5) Chicken parts 10) Fresh fruit its traditional products (raw sugar, green coffee, and cacao) to gold, Ferro-nickel, sugar derivatives, free-trade zone products, Consumer-Oriented Trade (U.S. -

I. the ECONOMIC and TRADE ENVIRONMENT (1) Major Features

Dominican Republic W/TPR/S/11 Page 1 I. THE ECONOMIC AND TRADE ENVIRONMENT (1) Major Features of the Economy1 1. The Dominican Republic is located in the eastern half of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (with Haiti on the western half). It has an area of 48,442 km2. In 1993, the population was around 7.5 million; population growth has declined to around 2 per cent in the 1990s from 2.7 per cent in the early 1970s. The urban population is increasing, amounting to 63 per cent of the total in 1993 (Table I.1). The Dominican Republic is endowed with different types of soil suitable for agriculture and is rich in minerals; its traditional production structure has been in agricultural goods such as sugar, coffee, cocoa, and tobacco and in the exploitation of minerals such as nickel, doré (a gold and silver alloy) and bauxite. The abundance of labour and the proximity to the United States have been important elements in the rapid growth of exports, mainly of clothing, from free zones (Chapter V(4)); furthermore, a buoyant tourist industry has developed around the many attractive beaches (Chapters V(5)). Table I.1 Major features of the Dominican Republic economy (1987 prices) 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1991 1992 1993 Population (thousands) 4,423 5,049 5,697 6,376 7,110 7,247 7,387 7,543 urban population (per cent) 40.0 45.3 50.5 55.7 60.4 61.2 62.1 62.9 Current GNP per capita (US$) 340 720 1160 760 890 1010 1170 1230 Labor force (thousands) 1,157 1,340 1,571 1,862 2,187 2,251 2,317 2,384 Female participation (per cent) 11.0 11.7 12.4 13.7 15.0 15.3 15.6 15.9 GDP at constant market prices GDP (US$ million) 2,184 3,345 4,240 4,588 5,493 5,545 5,975 6,151 Share in GDP Agriculture 27.6 20.9 20.0 20.3 16.0 16.5 16.2 15.8 Industry 23.7 29.2 28.4 26.2 24.6 23.5 24.6 24.2 Manufacturing 15.4 15.7 15.3 13.7 12.5 12.3 12.9 12.6 Services 48.6 49.9 51.6 53.5 59.4 60.1 59.2 60.0 School enrollment ratio Primary 100 104 118 126 .. -

When Christopher Columbus Came Ashore in 1492, He Wrote in His Diary

When Christopher Columbus came ashore in 1492, he wrote in his diary, “This is the most beautiful land that human eyes have seen.” He would leave members of his family behind to colonize the island and would return to it after venturing throughout the Caribbean. In his will, he asked to be buried in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. It was to this island a group of 22, mostly graduate nursing students and faculty from University of San Diego (www.sandiego.edu) , along with one dentist, would travel as a mission endeavor, to improve the health of school children of a rural school. Excitement ran high as the emails & gmails flashed back and forth, final arranges were gelling into a final plan. Were we actually going to the Caribbean? Over six months in the planning, and after 8 prior visits to La Republica Dominicana (Dominican Republic in English, indigenous Taino Indians called it Quisqueya), the trip was finally coming to fruition. It was decided that now was the time to include dental care in the overall plan to help the needy families far into the mountainous area near the international border with Haiti. Destination, El Cercado, to work at the school, Fe y Alegria (“Faith and Gladness”); the goal, examine students and their families in health screening as well as undertake a couple of research projects, one having to do with new techniques for diagnosing diabetes compared to traditional methods. But after having seen the severe need in oral disease, this was the year to begin inclusion of emergency dental care. -

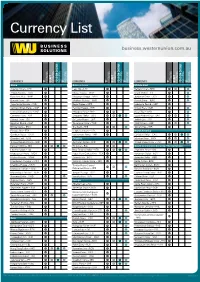

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Latin American Carbon Forum Hotel V Centenario Intercontinental Santo

Latin American Carbon Forum Hotel V Centenario Intercontinental Santo Domingo – Dominican Republic October 13-15, 2010 CDM in Latin American and the Caribbean INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS FORUM VENUE The Latin American Carbon Forum will be held from 13 to 15 October 2010, at the Hotel V CENTENARIO Intercontinental, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Address: HOTEL V CENTENARIO INTERCONTINENTAL Ave George Washington 218 Santo Domingo, 2890 Dominican Republic Front Desk: +1-809-221-0000 Fax: +1-809-221-2020 Web: http://www.ichotelsgroup.com/intercontinental/en/gb/locations/santodomingo Reservations: Hotel is minimum USD 109 per night plus 26% taxes in standard rooms. ACCOMMODATION Participants should make their own hotel and airport transfer bookings. A list of hotels near the venue: ***Stars BQ Hotel Av. Sarasota #53 Bella Vista, Santo Domingo 1818 Dominican Republic Tel: (809) 535-0800 Room types Room Type Single Double Extra Standard US$75.00 US$85.00 US$10.00 Superior US$90.00 US$100.00 Suite Superior US$115.00 US$125.00 Suite Royal US$130.00 US$140.00 Penthouse US$155.00 US$165.00 Rates per room per night, subject to 26% tax and service charges. INCLUSIONS • Breakfast buffet included in the Restaurant Casa Mencia. • Wireless Internet in rooms and included all areas of the Hotel. • Use of Fitness • roofing parking • wake up call ACCOMMODATION Two buildings of eight floors each, with 137 spacious rooms including 22 Suites and 4 Penthouses, Kitchenette and Jacuzzi available. All rooms are equipped with one or two queen beds, air conditioner, dual-line telephones and voice mail, cable TV, safe and hair dryer. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

General Information.Pdf

14 May 2008 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: SPANISH GENERAL INFORMATION 2008-326 1 INTRODUCTION The thirty-second session of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) will be held in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, from 9 to 13 June 2008. By resolution 631(XXXI), adopted at the thirty-first session of ECLAC (Montevideo, Uruguay, 20-24 March 2006), member States agreed that Santo Domingo would be the host city of the meeting. The session is the most important event of each biennium for ECLAC. It provides a forum for the consideration of issues of importance for the development of the countries of the region and an opportunity to review the activities of the Commission. The purpose of this document is to provide delegates attending the session with useful background information and logistical support to facilitate their work at the thirty-second session of ECLAC. Session coordinators will be pleased to answer any questions you may have concerning the logistics or organization of the event, whether before or during the session. 1. Programme of activities The thirty-second session of ECLAC will be held from Monday, 9 June, to Friday, 13 June 2008. The official opening ceremony will take place in the evening of Monday, 9 June (conference room 1). In the morning a press conference will be held on the thirty-second session of ECLAC at the National Palace (Palacio de Gobierno). The heads of delegation meeting will be held on Tuesday, 10 June, in conference room 2. The Executive Secretary will present the main session document in conference room 1. -

Currency List

Americas & Caribbean | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ANG Netherland Antillean Guilder ARS Argentine Peso BBD Barbados Dollar BMD Bermudian Dollar BOB Bolivian Boliviano BRL Brazilian Real BSD Bahamian Dollar CAD Canadian Dollar CLP Chilean Peso CRC Costa Rica Colon DOP Dominican Peso GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal GYD Guyana Dollar HNL Honduran Lempira J MD J amaican Dollar KYD Cayman Islands MXN Mexican Peso NIO Nicaraguan Cordoba PEN Peruvian New Sol PYG Paraguay Guarani SRD Surinamese Dollar TTD Trinidad/Tobago Dollar USD US Dollar UYU Uruguay Peso XCD East Caribbean Dollar 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Europe | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ALL Albanian Lek BGN Bulgarian Lev CHF Swiss Franc CZK Czech Koruna DKK Danish Krone EUR Euro GBP Sterling Pound HRK Croatian Kuna HUF Hungarian Forint MDL Moldovan Leu NOK Norwegian Krone PLN Polish Zloty RON Romanian Leu RSD Serbian Dinar SEK Swedish Krona TRY Turkish Lira UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Middle East | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverabl Non-Deliverabl Special Symbol Capability e Forward e Forward requirements/ Restrictions AED Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham BHD Bahraini Dinar ILS Israeli New Shekel J OD J ordanian Dinar KWD Kuwaiti Dinar OMR Omani Rial QAR Qatar Rial SAR Saudi Riyal 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. -

Viii Meeting of the Executive Committee of the Statistical Conference of the Americas of Eclac

UNITED NATIONS VIII MEETING OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE STATISTICAL CONFERENCE OF THE AMERICAS OF ECLAC Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 22 – 24 October 2008 GENERAL INFORMATION Meeting venue The VIII Meeting of the Executive Committee of the Statistical Conference of the Americas of ECLAC” will take place on 22, 23 and 24 October 2008, in the Hotel Renaissance Jaragua, located on Av. George Washington 367 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Registration of participants Registration of participants will begin on Monday 22 October, at 08:30 a.m. Inaugural Session The Seminar will be inaugurated at 09:00 a.m. Languages The official language of the meeting is Spanish. Simultaneous interpretation to English will be provided. Hotel reservations A limited number of rooms with special rates for participants have been blocked in the Renaissance Jaragua Hotel & Casino: Hotel Renaissance Jaragua (*****), Av. George Washington 367, apartado postal 769-2, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Telephone: (1-809) 221-2222 / 221-1476 Fax: (1-809) 686-0528 Toll free: 1-800-352-4354 Attention: Ms. Laura Terrero, Sales and Groups Manager Email: [email protected] Club Jardin Room: single or double US$ 90.00 (breakfast included) Luxury Tower Room: US$ 110.00 single with breakfast included Luxury Tower Room: US$ 115.00 double with breakfast included These rates are net per night, plus 26% tax and services charges. Requests for hotel reservations should be addressed directly to the hotel before 4 October. After this date, the hotel reserves the right to alter the rate offered and will not guarantee availability. To maintain the special rate given to participants, the hotel reservations must be requested personally and not through travel agencies or other means. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Country Currency Amount Argentina Argentina Peso 6,200 Australia Australian Dollar 3,300 Austria Euro 2,300 Belguim Euro 2,100 B

Referral payout amounts for referrals received on or after September 1, 2013. These award amounts will be valid through December 31, 2014. Payout amounts are reviewed annually. September 1, 2013 - December 31, 2014 EERP Payout Chart Country Currency Amount Argentina Argentina Peso 6,200 Australia Australian Dollar 3,300 Austria Euro 2,300 Belguim Euro 2,100 Brazil Reals 3,450 Bulgaria Lev 2,500 Canada Canadian Dollar 2,600 Chile Chilean Pesos 966,000 China RMB 6,000 Columbia COP 3300000 Costa Rica Costa Rica Colon 828,000 Czech Republic Koruna 38,800 Denmark Krone 21,400 Dominican Republic Dominican Peso 59,000 Egypt Egyptian Pound 8,500 Estonia Euro 1,600 Finland Euro 2,200 France Euro 2,350 Germany Euro 2,050 Hong Kong Hong Kong Dollar 16,000 Hungary Forint 387,000 India Rupee 47,600 Indonesia Rupiah 4,450,000 Ireland Euro 2,000 Italy Euro 2,200 Japan Yen 257,000 Jordan Dinar 1,370 Kenya Shilling 116,000 Korea Won 1,770,000 Kuwait Kuwaiti Dinar 592 Lithuania Litas 2,500 Luxembourg Euro 2,000 Malaysia Ringgit 4,200 Mexico Mexico Peso 22,800 Monaco Euro 2,300 Morroco MAD 14,600 Netherlands Euro 2,200 New Zealand New Zealand Dollar 2,950 Norway Kroner 21,800 Panama Balboa 1,460 Peru PEN 4,600 Poland Zloty 5,800 Qatar Rial 6,900 Romania New Lei 5,500 Russia Ruble 62,400 Revised Date: August 2013 Referral payout amounts for referrals received on or after September 1, 2013. These award amounts will be valid through December 31, 2014.