Assessment of the Effect of Local Versus General Anesthesia on the Pain Perception After Inguinal Hernia Surgery M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Anaesthesia in Oral Surgery and Outpatient Surgery History

Department of Oral- and Maxillofacial Surgery, Semmelweis University Budapest Head of Department: Dr. Németh Zsolt General anaesthesia in oral surgery and outpatient surgery History 1844 Horace Wells nitrous oxide extraction of one of his own wisdom teeth by a colleague 1846 William Morton (pupil of Wells) ether extraction 1946 introduction of lidocaine General anaesthesia should be strictly limited to those patients and clinical situations in which local anaesthesia (with or without sedation) is not an option. Bourne JG. General anaesthesia in the dental surgery. B Dental J 1962; 113: 54-7. Coleman F. The history of nitrous oxide anaesthesia. Dental Record 1942; 62: 143-9 Naveen Malhotra General Anaesthesia for Dentistry ndian Journal of Anaesthesia 2008;52:Suppl (5):725-737 Types of general anaesthesia Outpatient anaesthesia • Dental chair anaesthesia Relative analgesia for simple extraction • Day care anaesthesia Conscious sedation (Sedoanalgesia) for minor oral surgery In patient anaesthesia Intubation with or without neuromuscular blocking for complicated extractions, oral- and maxillofacial surgical procedures Indications of general anaesthesia • Acute infection (pain) • Children • Mentally challenged patients • Dental phobia • Allergy to local anaesthetics • Extensive dentistry & facio-maxillary surgery Equipments • anaesthesia machine, vaporizers • oxygen, nitrous oxide • breathing circuits (adult and pediatric) • nasal and facial masks • oral and nasal air-ways • different laryngoscopes with all sizes of blades • nasal and -

Methohexital(BAN, Rinn)

1788 General Anaesthetics metabolic pathways include hydroxylation of the 3. Lökken P, et al. Conscious sedation by rectal administration of Methohexital Sodium (BANM, rINNM) midazolam or midazolam plus ketamine as alternatives to gener- cyclohexone ring and conjugation with glucuronic ac- al anesthesia for dental treatment of uncooperative children. Compound 25398; Enallynymalnatrium; Méthohexital Sodique; id. The beta phase half-life is about 2.5 hours. Keta- Scand J Dent Res 1994; 102: 274–80. Methohexitone Sodium; Metohexital sódico; Natrii Methohexi- 4. Louon A, et al. Sedation with nasal ketamine and midazolam for talum. mine is excreted mainly in the urine as metabolites. It cryotherapy in retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol crosses the placenta. 1993; 77: 529–30. Натрий Метогекситал 5. Zsigmond EK, et al. A new route, jet-injection for anesthetic in- C14H17N2NaO3 = 284.3. ◊ References. duction in children–ketamine dose-range finding studies. Int J CAS — 309-36-4; 22151-68-4; 60634-69-7. 1. Clements JA, Nimmo WS. Pharmacokinetics and analgesic ef- Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996; 34: 84–8. ATC — N01AF01; N05CA15. fect of ketamine in man. Br J Anaesth 1981; 53: 27–30. 6. Kronenberg RH. Ketamine as an analgesic: parenteral, oral, rec- tal, subcutaneous, transdermal and intranasal administration. J ATC Vet — QN01AF01; QN05CA15. 2. Grant IS, et al. Pharmacokinetics and analgesic effects of IM and Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2002; 16: 27–35. oral ketamine. Br J Anaesth 1981; 53: 805–9. Pharmacopoeias. US includes Methohexital Sodium for In- jection. 3. Grant IS, et al. Ketamine disposition in children and adults. Br J Nonketotic hyperglycinaemia. -

Local Anaesthesia for Major General Surgical Postgrad Med J: First Published As 10.1136/Pgmj.72.844.105 on 1 February 1996

Postgrad Med J' 1996; 72: 105-108 C) The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1996 Local anaesthesia for major general surgical Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.72.844.105 on 1 February 1996. Downloaded from procedures A review of 1 16 cases over 12 years A Dennison, N Oakley, D Appleton, J Paraskevopoulos, D Kerrigan, J Cole, WEG Thomas Summary ation was collated from medical notes, anaes- Between 1980 and 1992, 116 patients had thetic records and operation notes. Cases in either a simple mastectomy (32) or intra- which local anaesthesia was augmented by abdominal procedures (84) under local regional or intravenous techniques were exc- anaesthesia (0.5-1% lignocaine with luded from the study. Patients were not 1:200 000 adrenaline). A wide variety of included ifthey had neck/head or limb surgery, general surgical procedures were feasible abdominal hernia repair, simple drainage of using only supplementary intravenous intra-abdominal abscess or any minor proce- sedation (54%). Complications were un- dures including peritoneo-venous shunts, common and related to surgical proce- laparoscopic or endoscopic procedures. dure (three incorrect diagnoses, three The 116 patients presented in the study are procedures impossible) rather than the those who had intra-abdominal surgery (84; 53 anaesthetic technique. There were no women, 31 men) or simple mastectomy (32). anaesthetic toxicity or postoperative pro- The median age was 74 years (range 27-92) blems. Local anaesthesia is extremely and all the patients were grade III or worse on safe and facilitates larger surgical proce- the American Society of Anaesthesiologists dures than is generally appreciated. -

Nerve Blocks for Surgery on the Shoulder, Arm Or Hand

Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand Information for patients and families First Edition 2015 www.rcoa.ac.uk/patientinfo Nerve blocks for surgery on the shoulder, arm or hand This leaflet is for anyone who is thinking about having a nerve block for an operation on the shoulder, arm or hand. It will be of particular interest to people who would prefer not to have a general anaesthetic. The leaflet has been written with the help of patients who have had a nerve block for their operation. Throughout this leaflet we have used the above symbol to highlight key facts. Brachial plexus block? The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that lies between your neck and your armpit. It contains all the nerves that supply movement and feeling to your arm – from your shoulder to your fingertips. A brachial plexus block is an injection of local anaesthetic around the brachial plexus. It ‘blocks’ information travelling along these nerves. It is a type of nerve block. Your arm becomes numb and immobile. You can then have your operation without feeling anything. The block can also provide excellent pain relief for between three and 24 hours, depending on what kind of local anaesthetic is used. A brachial plexus block rarely affects the rest of the body so it is particularly advantageous for patients who have medical conditions which put them at a higher risk for a general anaesthetic. A brachial plexus block may be combined with a general anaesthetic or with sedation. This means you have the advantage of the pain relief provided by a brachial plexus block, but you are also unconscious or sedated during the operation. -

Femoral Nerve Block Versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44 Femoral Nerve Block versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Surgery By Ahmed Mansour, MD Assistant Professor of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University. Abstract Perioperative cardiac complications occur in 4% to 6% of patients undergoing infrainguinal revascularization under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. The risk may be even greater in patients whose cardiac disease cannot be fully evaluated or treated before urgent limb salvage operations. Prompted by these considerations, we investigated the feasibility and results of using femoral nerve block with infiltration of the genito4femoral nerve branches in these high-risk patients. Methods: Forty peripheral vascular reconstruction of lower limbs were performed under either spinal anesthesia (20 patients) or femoral nerve block with infiltration of genito-femoral nerve branches supplemented with local infiltration at the site of dissection as needed (20 patients). All patients had arterial lines. Arterial blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring was continued during surgery, in PACU and in the intensive care units. Results: Operations included femoral-femoral, femoral-popliteal bypass grafting and thrombectomy. The intra-operative events showed that the mean time needed to perform the block and dose of analgesics and sedatives needed during surgery was greater in group I (FNB,) compared to group II [P=0.01*, P0.029* , P0.039*], however, the time needed to start surgery was shorter in group I than in group II [P=0. 039]. There were no block failures in either group, but local infiltration in the area of the dissection with 2 ml (range 1-5 ml) of 1% lidocaine was required in 4 (20%) patients in FNB group vs none in the spinal group. -

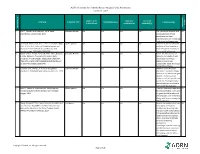

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table SAMPLE SIZE/ CONTROL/ OUTCOME CITATION EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTION(S) CONCLUSION(S) POPULATION COMPARISON MEASURE(S) SCORE CONSENSUS REFERENCE # REFERENCE 1 Lirk P., Picardi S. and Hollmann, M. W. Local Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a The mechanism of action and VA anaesthetics: 10 essentials. 2014 access pathways of local anesthetics and their pharmokinetics are increasingly understood and appreciated. 2 Calatayud, Jesús, M.D.,D.D.S., Ph.D., González, Õngel, Expert Opinion n/a n/a n/a n/a A review of the discovery and VA M.D., D.D.S., Ph.D. History of the development and evolution of local anesthesia evolution of local anesthesia since the coca leaf. from the Spanish discovery of Anesthesiology. 2003;98(6):1503-1508. the coca leaf in America. 3 Gordh T, M.D., Gordh, Torsten E.,M.D., Ph.D., Lindqvist Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Before the introduction of VA K, M.Sc. Lidocaine: The origin of a modern local lidocaine, the choice of local anesthetic. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1433-1437. anesthetics was limited. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. doi: Lidocaine's onset was 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. substantially faster and longer lasting than procaine. 4 Volcheck G.W., Mertes, P. M. Local and general Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Whether to test the local VA anesthetics immediate hypersensitivity reactions. 2014 anesthetic causing the allergic reaction or an alternative agent depends on the expected future need of the specific local anesthetic. -

The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures

Volume 2- Issue 1 : 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000695 Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Mini Review Open Access The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada MD* Received: January 17, 2018; Published: January 25, 2018 *Corresponding author: Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada, Ex-Professor of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, Teresópolis Schoolof Medicine, Rio de Janeiro, Rua Jose da Silva Ribeiro 119 apt 11 São Paulo, SP Brazil CEP: 05726-130, Email: Abstract The local anesthetics are widely u sed in minor pediatric surgical procedures. The major problem with their use is the resulted pain experienced by the patients at the time of injection. To discuss those situations in the light of the medical literature we present this mini-review. Key words: Local Injection; Pain; Buffer; pH; Lidocaine; Pediatric Surgery Procedure Introduction Table 1: Techniques for injection pain control*. a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) cream [17] S.No Techniques for injection pain control before infiltration, and local external cooling (cryoanalgesia) have 1. Warming the anesthetic solution [18,19] (Table 1). also been used to reduce the pain of infiltration of local anesthetic 2. Buffering the anesthetic Buffering the Anesthetic 3. Injection technique 4. Distraction Local anesthesia is extremely useful either as the sole method the best results on the minor surgery in general [3,6]. Blocking 5. Combination anesthetic technique the pain pathway with local anesthetic solution will also reduce 6. Cooling of skin the family stress response to the surgical procedure. -

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3Rd Edition, Version G

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3rd Edition, Version G I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Veterinary Formulary II. Anesthetic and Analgesic Considerations III. Species Specific Veterinary Formulary 1. Mouse 2. Rat 3. Neonatal Rodent 4. Guinea Pig 5. Chinchilla 6. Gerbil 7. Rabbit 8. Dog 9. Pig 10. Sheep 11. Non‐Pharmaceutical Grade Anesthetics IV. References I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Formulary Basic Definitions: Anesthesia: central nervous system depression that provides amnesia, unconsciousness and immobility in response to a painful stimulation. Drugs that produce anesthesia may or may not provide analgesia (1, 2). Analgesia: The absence of pain in response to stimulation that would normally be painful. An analgesic drug can provide analgesia by acting at the level of the central nervous system or at the site of inflammation to diminish or block pain signals (1, 2). Sedation: A state of mental calmness, decreased response to environmental stimuli, and muscle relaxation. This state is characterized by suppression of spontaneous movement with maintenance of spinal reflexes (1). Animal anesthesia and analgesia are crucial components of an animal use protocol. This document is provided to aid in the design of an anesthetic and analgesic plan to prevent animal pain whenever possible. However, this document should not be perceived to replace consultation with the university’s veterinary staff. As required by law, the veterinary staff should be consulted to assist in the planning of procedures where anesthetics and analgesics will be used to avoid or minimize discomfort, distress and pain in animals (3, 4). Prior to administration, all use of anesthetics and analgesic are to be approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). -

An Introduction to Anaesthesia

What You Need to KNoW about An introduction to anaesthesia Introduction divided into three stages: induction, main- n Central neuraxial block, e.g. spinal or Anaesthetic experience in the undergradu- tenance and emergence. epidural (Figure 1 and Table 1). ate timetable is often very limited so it can In regional anaesthesia, nerve transmis- remain somewhat of a mysterious practice sion is blocked, and the patient may stay Components of a general well into specialist training. This introduc- awake or be sedated or anaesthetized dur- anaesthetic tion to the components of an anaesthetic ing a procedure. Techniques used include: A general anaesthetic always involves an will help readers to get more from clinical n Local anaesthetic field block hypnotic agent, usually an analgesic and attachments in surgery and anaesthetics or n Peripheral nerve block may also include muscle relaxation. The serve as an introduction to the topic for n Nerve plexus block combination is referred to as the ‘triad of novice or non-anaesthetists. anaesthesia’. Figure 1. Schematic vertical longitudinal section The relative importance of each com- Types and sites of anaesthesia of vertebral column and structures encountered ponent depends on surgical and patient The term anaesthesia comes from the when performing central neuraxial blocks. * factors: the intervention planned, site, Greek meaning loss of sensation. negative pressure space filled with fat and surgical access requirement and the Anaesthetic practice has evolved from a venous plexi. † extends to S2, containing degree of pain or stimulation anticipated. need for pain relief and altered conscious- arachnoid mater, CSF, pia mater, spinal cord The technique is tailored to the individu- ness to allow surgery. -

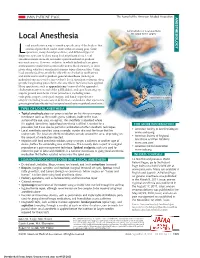

Local Anesthesia for Carpal Tunnel Surgery

JAMA PATIENT PAGE The Journal of the American Medical Association ANESTHESIOLOGY Administration of local anesthetic Local Anesthesia for carpal tunnel surgery ocal anesthesia is a way to numb a specific area of the body so that a medical procedure can be done without causing pain. Some Loperations, many dental procedures, and different types of diagnostic tests can be done using local anesthesia alone. Local anesthesia medications do not make a person sedated or produce unconsciousness. However, sedation, in which individuals are given medications to make them comfortable and to block memory, is often given along with local anesthesia for many types of procedures. Using local anesthesia alone avoids the side effects of sedation medications and medications used to produce general anesthesia (making an individual unconscious for a procedure). Local anesthetic solutions often provide long-lasting pain relief to the area where they have been applied. Many operations, such as appendectomy (removal of the appendix), cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder), and open heart surgery, require general anesthesia. Other procedures, including some orthopedic surgery, urological surgery, and female reproductive Carpal tunnel surgery surgery (including most cesarean deliveries), can be done after a person is given regional anesthesia (such as spinal anesthesia or epidural anesthesia). TYPES OF LOCAL ANESTHESIA • Topical anesthesia places or sprays a solution on the skin or a mucous membrane (such as the mouth, gums, eardrum, inside of the nose, surface of the eye, anus, or vagina). The anesthetic is absorbed where it is applied. Sometimes topical local anesthesia is all that is needed for a FOR MORE INFORMATION procedure, but it can also be part of a combination of other anesthetic techniques. -

Veterinary Anesthesia and Pain Management Secrets / Edited by Stephen A

Publisher: HANLEY & BELFUS, INC. Medical Publishers 210 South 13th Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 546-7293; 800-962-1892 FAX (215) 790-9330 Web site: http://www.hanleyandbelfus.com Note to the reader Although the information in this book has been carefully reviewed for cor rectness of dosage and indications, neither the authors nor the editor nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. Neither the publisher nor the editor makes any warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. Before prescribing any drug. the reader must review the manu facturer's correct product information (package inserts) for accepted indications, absolute dosage recommendations. and other information pertinent to the safe and effective use of the product described. This is especially important when drugs are given in combination or as an adjunct to other forms of therapy Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veterinary anesthesia and pain management secrets / edited by Stephen A. Greene. p. em. - (The Secrets Series®) Includes bibliographical references (p.). ISBN 1-56053-442-7 (alk paper) I. Veterinary anesthesia-Examinations, questions. etc. 2. Pain in animals Treatment-Examinations, questions, etc. I. Greene, Stephen A., 1956-11. Series. SF914.V48 2002 636 089' 796'076--dc2 I 2001039966 VETERINARY ANESTHESIA AND PAIN MANAGEMENT SECRETS ISBN 1-56053-442-7 © 2002 by Hanley & Belfus, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro duced, reused, republished. or transmitted in any form, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 CONTRIBUTORS G. -

2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats*

VETERINARY PRACTICE GUIDELINES 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats* Tamara Grubb, DVM, PhD, DACVAAy, Jennifer Sager, BS, CVT, VTS (Anesthesia/Analgesia, ECC)y, James S. Gaynor, DVM, MS, DACVAA, DAIPM, CVA, CVPP, Elizabeth Montgomery, DVM, MPH, Judith A. Parker, DVM, DABVP, Heidi Shafford, DVM, PhD, DACVAA, Caitlin Tearney, DVM, DACVAA ABSTRACT Risk for complications and even death is inherent to anesthesia. However, the use of guidelines, checklists, and training can decrease the risk of anesthesia-related adverse events. These tools should be used not only during the time the patient is unconscious but also before and after this phase. The framework for safe anesthesia delivered as a continuum of care from home to hospital and back to home is presented in these guidelines. The critical importance of client commu- nication and staff training have been highlighted. The role of perioperative analgesia, anxiolytics, and proper handling of fractious/fearful/aggressive patients as components of anesthetic safety are stressed. Anesthesia equipment selection and care is detailed. The objective of these guidelines is to make the anesthesia period as safe as possible for dogs and cats while providing a practical framework for delivering anesthesia care. To meet this goal, tables, algorithms, figures, and “tip” boxes with critical information are included in the manuscript and an in-depth online resource center is available at aaha.org/anesthesia. (J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2020; 56:---–---. DOI 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-7055) AFFILIATIONS Other recommendations are based on practical clinical experience and From Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Pullman, a consensus of expert opinion.