University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Gallery of Art (NGA) Is Hosting a Special Tribute and Black

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 MEDIA ADVISORY WHAT: The National Gallery of Art (NGA) is hosting a Special Tribute and Black-tie Dinner and Reception in honor of the Founding and Retiring Members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC). This event is a part of the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation's (CBCF) 20th Annual Legislative Weekend. WHEN: Wednesday, September 26, 1990 Working Press Arrival Begins at 6:30 p.m. Reception begins at 7:00 p.m., followed by dinner and a program with speakers and a videotape tribute to retiring CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA) , Walter E. Fauntroy (DC), and George Crockett (MI) . WHERE: National Gallery of Art, East Building 4th Street and Constitution Ave., N.W. SPEAKERS: Welcome by J. Carter Brown, director, NGA; Occasion and Acknowledgements by CBC member Kweisi Mfume (MD); Invocation by CBC member The Rev. Edolphus Towns (NY); Greetings by CBC member Alan Wheat (MO) and founding CBC member Ronald Dellums (CA); Presentation of Awards by founding CBC members John Conyers, Jr. (MI) and William L. Clay (MO); Music by Noel Pointer, violinist, and Dr. Carol Yampolsky, pianist. GUESTS: Some 500 invited guests include: NGA Trustee John R. Stevenson; (See retiring and founding CBC members and speakers above.); Founding CBC members Augustus F. Hawkins (CA), Charles B. Rangel (NY), and Louis Stokes (OH); Retired CBC founding members Shirley Chisholm (NY), Charles C. Diggs (MI), and Parren Mitchell (MD) ; and many CBC members and other Congressional leaders. Others include: Ronald Brown, Democratic National Committee; Sharon Pratt Dixon, DC mayoral candidate; Benjamin L Hooks, NAACP; Dr. -

Rediscover Northern Ireland Report Philip Hammond Creative Director

REDISCOVER NORTHERN IRELAND REPORT PHILIP HAMMOND CREATIVE DIRECTOR CHAPTER I Introduction and Quotations 3 – 9 CHAPTER II Backgrounds and Contexts 10 – 36 The appointment of the Creative Director Programme and timetable of Rediscover Northern Ireland Rationale for the content and timescale The budget The role of the Creative Director in Washington DC The Washington Experience from the Creative Director’s viewpoint. The challenges in Washington The Northern Ireland Bureau Publicity in Washington for Rediscover Northern Ireland Rediscover Northern Ireland Website Audiences at Rediscover Northern Ireland Events Conclusion – Strengths/Weaknesses/Potential Legacies CHAPTER III Artist Statistics 37 – 41 CHAPTER IV Event Statistics 42 – 45 CHAPTER V Chronological Collection of Reports 2005 – 07 46 – 140 November 05 December 05 February 06 March 07 July 06 September 06 January 07 CHAPTER VI Podcasts 141 – 166 16th March 2007 31st March 2007 14th April 2007 1st May 2007 7th May 2007 26th May 2007 7th June 2007 16th June 2007 28th June 2007 1 CHAPTER VII RNI Event Analyses 167 - 425 Community Mural Anacostia 170 Community Poetry and Photography Anacostia 177 Arts Critics Exchange Programme 194 Brian Irvine Ensemble 221 Brian Irvine Residency in SAIL 233 Cahoots NI Residency at Edge Fest 243 Healthcare Project 252 Camerata Ireland 258 Comic Book Artist Residency in SAIL 264 Comtemporary Popular Music Series 269 Craft Exhibition 273 Drama Residency at Catholic University 278 Drama Production: Scenes from the Big Picture 282 Film at American Film -

Blood and Oil

A Presentation of the Media Education Foundation Michael T. Klare’s BLOOD AND OIL “Our military policy and our energy policy have become intertwined. They have become one and the same… And if we continue to rely on military force to solve our resource needs, we’re in for a very bloody and dangerous and painful century indeed.” – Michael Klare in Blood and Oil Running Time: 52 minutes For further information about this film or to arrange interviews with Michael Klare or the film’s producers, please contact: Scott Morris | Producer/Co-Writer/Co-Editor | tel 413.584.8500 ext. 2216 | cell 978.204.8831 | email [email protected] For high-resolution images from the film, visit: www.bloodandoilmovie.com/pressroom.html 2 EARLY PRAISE FOR BLOOD AND OIL “Blood and Oil is a compelling, credible and thought-provoking history lesson for all Americans. A must-see for current and older generations who served America's militaristic pursuit of oil, and for their children who will soon be required to conduct a serious intervention at home to heal this nation's blood for oil compulsion.” Lt. Col. Karen Kwiatkowski, Air Force (Ret.) “Michael Klare's analysis of the role of oil in US foreign policy since 1945 is indispensable to an understanding of the critical problems we face. I hope that this lucid and historically accurate film is widely seen.” Chalmers Johnson, author of the Blowback Trilogy “Michael Klare looks into the future with sharper eyes than almost anyone else around. Pay attention!” Bill McKibben, author of The End of Nature “Digging into the archives of military history, Klare discerns a clear pattern: presidential commitment to oil addiction entails mounting costs and loss of life. -

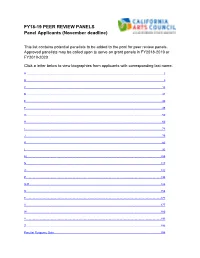

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with the Honorable Sharon Pratt

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with The Honorable Sharon Pratt PERSON Kelly, Sharon Pratt, 1944- Alternative Names: The Honorable Sharon Pratt; Sharon Pratt Kelly; Sharon Pratt Dixon Life Dates: January 30, 1944- Place of Birth: Washington, District of Columbia, USA Residence: Washington, D.C. Work: Washington, D.C. Occupations: Mayor Biographical Note Former Washington, D.C. Mayor Sharon Pratt was born on January 30, 1944 in Washington, D.C. Pratt is the daughter of Mildred Petticord and Carlisle Edward Pratt. Pratt graduated from Roosevelt High School in 1961 and earned her B.S. degree in political science in 1965 from Howard University. Pratt attended Howard University Law School where she earned her J.D. University Law School where she earned her J.D. degree in 1968. Pratt served as in-house counsel for the Joint Center for Political Studies from 1970 to 1971. From 1971 to 1976, she worked as an associate for the law firm Pratt & Queen PC. In 1972, Pratt became a law professor at the Antioch School of Law in Washington, D.C., and worked there until 1976 when she became the Associate General Counsel for the Potomac Electric Power Company, known as PEPCO. In 1982, Pratt directed the failed mayoral campaign for Patricia Robert Harris. That same year, Pratt married Arrington Dixon, a Democratic Washington, D.C. City Councilman. Pratt was promoted to the Director of Consumer Affairs for the Potomac Electric Power Company in 1979 and then later to Vice President of Consumer Affairs in 1983. In 1988, Pratt announced that she would challenge Mayor Marion Barry in the 1990 mayoral election in Washington, D.C. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, APRIL 15, 2008 No. 59 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. Speaker NANCY PELOSI on 4–24–2006: But before we achieve those things in f Democrats have a commonsense plan the future, we’ll have to figure out a to help bring down skyrocketing gas way to live, work, and prosper in the MORNING-HOUR DEBATE prices. present. For too many Democrats, The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the August 4, 2007, Democrats have voted growing our economy today, tomorrow, order of the House of January 4, 2007, those four times to raise taxes in the and next month isn’t much of a pri- the Chair will now recognize Members 110th Congress: January 18, August 4, ority. In fact, the majority has voted from lists submitted by the majority December 6, 2007, February 27, 2008. The four separate times to raise energy and minority leaders for morning-hour Pelosi Premium continues. taxes in the 110th Congress. But even if debate. Since Democrats took control of Con- we had access to all of the oil in the The Chair will alternate recognition gress, gasoline prices have skyrocketed world, we would need places to turn between the parties, with each party by more than $1 per gallon forcing that oil into gasoline. Regrettably, the limited to 30 minutes and each Mem- worker families to pay a Pelosi Pre- U.S. -

Kelly, Sharon Pratt

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 1-26-2016 Kelly, Sharon Pratt DPAAC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, DPAAC, "Kelly, Sharon Pratt" (2016). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 249. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/249 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guide to the Sharon Pratt Kelly Papers DCAAP.0021 Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Collection Number 228 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by D.C. Africana Archives Project This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit January 26, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard DC Africana Archives Project Gelman Library Special Collections, Suite 704 2130 H Street NW Washington DC, 20052 Guide to the Sharon Pratt Kelly Papers DCAAP.0021 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note.............................................................................................................................. -

Walter Edward Washington (1915-2003): a Photo Tribute

Washington History in the Classroom This article, © the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is provided free of charge to educators, parents, and students engaged in remote learning activities. It has been chosen to complement the DC Public Schools curriculum during this time of sheltering at home in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Washington History magazine is an essential teaching tool,” says Bill Stevens, a D.C. public charter school teacher. “In the 19 years I’ve been teaching D.C. history to high school students, my scholars have used Washington History to investigate their neighborhoods, compete in National History Day, and write plays based on historical characters. They’ve grappled with concepts such as compensated emancipation, the 1919 riots, school integration, and the evolution of the built environment of Washington, D.C. I could not teach courses on Washington, D.C. Bill Stevens engages with his SEED Public Charter School history without Washington History.” students in the Historical Society’s Kiplinger Research Library, 2016. Washington History is the only scholarly journal devoted exclusively to the history of our nation’s capital. It succeeds the Records of the Columbia Historical Society, first published in 1897. Washington History is filled with scholarly articles, reviews, and a rich array of images and is written and edited by distinguished historians and journalists. Washington History authors explore D.C. from the earliest days of the city to 20 years ago, covering neighborhoods, heroes and she-roes, businesses, health, arts and culture, architecture, immigration, city planning, and compelling issues that unite us and divide us. -

Entire Issue

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, APRIL 15, 2008 No. 59 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. Speaker NANCY PELOSI on 4–24–2006: But before we achieve those things in f Democrats have a commonsense plan the future, we’ll have to figure out a to help bring down skyrocketing gas way to live, work, and prosper in the MORNING-HOUR DEBATE prices. present. For too many Democrats, The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the August 4, 2007, Democrats have voted growing our economy today, tomorrow, order of the House of January 4, 2007, those four times to raise taxes in the and next month isn’t much of a pri- the Chair will now recognize Members 110th Congress: January 18, August 4, ority. In fact, the majority has voted from lists submitted by the majority December 6, 2007, February 27, 2008. The four separate times to raise energy and minority leaders for morning-hour Pelosi Premium continues. taxes in the 110th Congress. But even if debate. Since Democrats took control of Con- we had access to all of the oil in the The Chair will alternate recognition gress, gasoline prices have skyrocketed world, we would need places to turn between the parties, with each party by more than $1 per gallon forcing that oil into gasoline. Regrettably, the limited to 30 minutes and each Mem- worker families to pay a Pelosi Pre- U.S. -

A Visit Through History: Historical Council Photograghs

A VISIT THROUGH HISTORY: HISTORICAL COUNCIL PHOTOGRAGHS Photographs Courtesy of the Washingtoniana Division, DC Public Library; D.C. Archives; Gelman Library at George Washington University; Smithsonian Institution – Spurlock Collection. A VISIT THROUGH HISTORY: HISTORICAL COUNCIL PHOTOGRAPHS Council of the District of Columbia – Office of the Secretary THE JOHN A. WILSON BUILDING: A CENTENNIAL OVERVIEW Some Important Facts, Dates and Events Associated with the Seat of Government of the District of Columbia 1902 Congress enacts legislation acquiring Square 255 and authorizing construction of a permanent seat of government for the District of Columbia (June 6). 1908 District (Wilson) Building is dedicated. Speakers and guests include Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and Mayors of Baltimore and Richmond. Declaration of Independence is read by a member of the Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia. Thousands attend the ceremony and tour the building (July 4). 1909 Bust of Crosby Stuart Noyes is unveiled in District (Wilson) Building. Funds are privately raised to commission the bust. Noyes (1825-1908) had been the editor of The Washington Evening Star. In 1888, Noyes persuaded the U.S. Senate for the first time ever to draft and consider a proposal to give D.C. voting representation in both the U.S. House and Senate. Throughout his life, Noyes advocated voting rights for residents of the District of Columbia (February 25). 1909 The Statue of Governor Alexander Robey Shepherd (1835-1902), a D.C. native, is unveiled in front of the District (Wilson) Building (May 3). Until 2005, when a statue of D.C. -

MS 0766 Loretta Carter Hanes Collection, 1749-2005

801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 www.DCHistory.org SPECIAL COLLECTIONS FINDING AID Title: MS 0766 Loretta Carter Hanes collection, 1749-2005 Processor: Marianne Gill Processed Date: 2014; additional series, objects, and textiles remain in the processing queue as of 2017 [Finding Aid last updated March 2017] Loretta Carter Hanes (1926-2016), a native Washingtonian, was a member of the Carter and Quander families. She was a descendent of enslaved people who lived and worked at George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate, and she was a dedicated volunteer to the school children of Washington, D.C. She is perhaps best recognized for her contributions to the Reading is Fundamental (RIF) program and the establishment of Emancipation Day as a municipal holiday in Washington, D.C. Born in 1926 in Washington, D.C., Loretta often accompanied her mother to her part time job as a cook at Stoddard Baptist Home. There she listened to the residents’ stories, including advice from a 102-year-old former slave who always talked about the need of everyone to help others by “bringing others across the bridge.” After graduating from Armstrong High School and Miner Teacher’s College, Loretta and her husband Wesley opened their home to tutor the neighborhood youth. Eventually a club was formed with 30 members who were taken on field trips to parks in the city for ball games. Reading is Fundamental, a program established November 1, 1966 at the urging of Mrs. Margaret McNamara, is a national program to provide school children with their own books. With offices in the Smithsonian Institution, and the financial support of foundation grants and industry contributions, RIF, by 1986, had 3100 projects in all 50 states and three territories. -

Rhona Friedman Confirmation Resolution of 2020”

COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE DRAFT COMMITTEE REPORT 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20004 TO: All Councilmembers FROM: Chairman Phil Mendelson Committee of the Whole DATE: January 21, 2020 SUBJECT: Report on PR 23-577, “Commission on the Arts and Humanities Rhona Friedman Confirmation Resolution of 2020” The Committee of the Whole, to which PR 23-577, “Commission on the Arts and Humanities Rhona Friedman Confirmation Resolution of 2020” was referred, reports favorably thereon with technical amendments, and recommends approval by the Council. CONTENTS I. Background And Need ...............................................................1 II. Legislative Chronology ..............................................................4 III. Position Of The Executive .........................................................5 IV. Comments Of Advisory Neighborhood Commissions ..............5 V. Summary Of Testimony .............................................................5 VI. Impact On Existing Law ............................................................6 VII. Fiscal Impact ..............................................................................6 VIII. Section-By-Section Analysis .....................................................6 IX. Committee Action ......................................................................6 X. Attachments ...............................................................................6 I. BACKGROUND AND NEED On November 26, 2019, Proposed Resolution 23-577,