Emerging from Lockdown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Postdramatic Television Series: the Art of Poetry and the Composition of Chaos (How to Understand the Script of the Best American Television Series)”

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72 – Pages 500 to 520 Funded Research | DOI: 10.4185/RLCS, 72-2017-1176| ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2017 How to cite this article in bibliographies / References MA Orosa, M López-Golán , C Márquez-Domínguez, YT Ramos-Gil (2017): “The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos (How to understand the script of the best American television series)”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 500 to 520. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/072paper/1176/26en.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1176 The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos How to understand the script of the best American television series Miguel Ángel Orosa [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Mónica López Golán [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – moLó[email protected] Carmelo Márquez-Domínguez [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – camarquez @pucesi.edu.ec Yalitza Therly Ramos Gil [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The magnitude of the (post)dramatic changes that have been taking place in American audiovisual fiction only happen every several hundred years. The goal of this research work is to highlight the features of the change occurring within the organisational (post)dramatic realm of American serial television. -

A Process Evaluation of the NCVLI Victims' Rights Clinics

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Finally Getting Victims Their Due: A Process Evaluation of the NCVLI Victims’ Rights Clinics Author: Robert C. Davis, James Anderson, Julie Whitman, Susan Howley Document No.: 228389 Date Received: September 2009 Award Number: 2007-VF-GX-0004 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Finally Getting Victims Their Due: A Process Evaluation of the NCVLI Victims’ Rights Clinics Abstract Robert C. Davis James Anderson RAND Corporation Julie Whitman Susan Howley National Center for Victims of Crime August 29, 2009 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Burial Grounds “They Say That Freedom Is a Constant

How To Be American: A Podcast by the Tenement Museum Season 2, Episode 3: Burial Grounds “They say that freedom is a constant struggle...they say that freedom is a constant struggle… they say that freedom is a constant struggle...get on a board boy, get on a board…” - Carl Johnson, Tenement Talk attendee, October 2019 Black Placemaking event. [Carl signing fades down] [Reflective music] Amanda Adler Brennan: This is Carl Johnson. Johnson attended an event at the Tenement Museum on the evening of October 17th, 2019. It was called Black Placemaking: Reinterpreting Lower East Side History. The event was about the exclusion of black experiences and community building from public memory over the course of American History...how the absence of dedicated place names, memorials and physical sites can render their presence invisible from certain neighborhoods, or even cities. And this is an exclusion that reinforces the existing order of how Black History is interpreted in this country. Memory is such a tricky thing. How we recall American History—the way it’s recorded, taught and told from one generation to the next...along the way, stories are sometimes forgotten. Other times, they’re willfully ignored. Before you know it, critical parts of stories, its characters—well...they’re erased. When history is forgotten or hidden...how do we make it whole? That takes me back to Carl Johnson. In a room full of strangers, he stood up and sang to another member of the audience, who asked the panelists: “How do we be resilient...how do we interpret our struggle, when there are things that we don’t see?” It was a mic-drop kind of moment when Johnson answered with a song, and not just any song. -

Libby Manning: the Joy of Learning – Season 2, Episode 1

Libby Manning: The Joy of Learning – Season 2, Episode 1 Amy: You’re listening to Beyond 1894, a podcast where we hear from Louisiana Tech University scholars, innovators, and professionals on their personal journeys and the impact they’re making in the word around them. I’m your host Amy Bell and my co-host is Teddy Allen. *school bell rings with light piano intro as students shuffle along and walk to class* Amy: In this episode, we will hear from Dr. Libby Manning. She has been a professor here at Tech for about 10 years in the College of Education, teaching Curriculum, Instruction, and Leadership. In our interview, we talked about her experiences as a teacher, her teaching philosophy, and some of her teaching strategies. She even mentioned how she has had to adapt her teaching, due to COVID-19 and physical distancing. Libby: So, what I discovered is they… We built communities often around novels, around characters and books, because when you live through “Number the Stars” or you live through “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry,” and you go along these journeys with these characters, you can’t help but be moved by that and you can’t help but feel like you as a class somehow got them through those struggles. And they become a part of who you are. Books do, they become a part of you. Amy: The passion Dr. Manning has for her teaching is truly inspiring. After interviewing her, I was motivated to try a little harder to be a better person. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Lure of the Lost

CREDITS LURE OF THE LOST COVER ART WRITING AND DEVELOPMENT Magali Villeneuve Jordan Goldfarb with Daniel Lovat Clark and Chris Gerber INTERIOR ART BASED ON Cristi Balanescu, Mark Behm, Sara Betsy, Ekaterina The FORCE AND DESTINY Roleplaying Game designed Burmak, Anna Christenson, Laura Csajagi, Tony Foti, by Jay Little and developed by Sam Stewart Zachary Graves, Jeff Lee Johnson, Aldo Katayanagi, Skott Kilander, David Nash, Mike Nash, Cynthia Shep- MANAGING RPG PRODUCER pard, Matt Zeilinger, and the Lucasfilm art archives Chris Gerber PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT EDITING AND PROOFREADING Megan Duehn and Simone Elliot Christine Crabb and David Johnson EXECUTIVE GAME DESIGNER GRAPHIC DESIGN Corey Konieczka Chris Beck EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GRAPHIC DESIGN MANAGER Michael Hurley Brian Schomburg PUBLISHER ART DIRECTION Christian T. Petersen Zoë Robinson PLAYTESTERS Curtis Hill, Tim Huckelbery, Mack Dalla Lana, MANAGING ART DIRECTOR Danny Schaefer, Andrew Schumacher, Tyler Soberanis Andy Christensen LUCASFILM CREATIVE DIRECTOR SENIOR EDITOR LUCASFILM STORY GROUP Michael Siglain Jennifer Heddle Leland Chee and Pablo Hidalgo FANTASY Fantasy Flight Games FLIGHT 1995 West County Road B2 GAMES Roseville, MN 55113 USA © & TM Lucasfilm Ltd. Fantasy Flight Games and the FFG Logo are registered trademarks of Fantasy Flight Publishing, Inc. PERMISSION GRANTED TO PRINT OR PHOTOCOPY ALL PAGES OF THIS BOOK FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY For more information about the Star Wars: FORCE AND DESTINY line, free downloads, answers to rule queries, or just to pass on greetings, visit us online at www.FantasyFlightGames.com LURE OF THE LOST 2 force and destiny LURE OF THE LOST "If a thing is lost, it can be found. If a person is lost, he must find himself." –Spintiri Proverb THE STORY SO FAR URE OF THE LOST is an adventure for the Star Wars: FORCE exact events of MOUNTAINTOP RESCUE, the PCs have secured L AND DESTINY BEGINNER GAME. -

Second Thoughts Exodus 13:20-14:31 3-28-2021 Charles

Second Thoughts Exodus 13:20-14:31 3-28-2021 Charles Swindoll told the story of nine-year-old Danny who came bursting out of his Sunday School class one Sunday like a wild stallion. His eyes were darting in every direction as he tried to locate his mom and dad. After a quick search he grabbed his dads’ leg and, in his excitement, yelled, “man, that story of Moses and all those people crossing the Red Sea was great! His father looked at him and smiled and asked his son to tell him about it. Well, the Israelites got out of Egypt, but Pharaoh and his army chased after them. So the Jews ran as fast as they could until they got to the Red Sea. The Egyptian army was getting closer and closer. So Moses got on his walkie-talkie and told the Israeli air force to bomb the Egyptians. While that was happening, the Israeli navy built pontoon bridges so the people could cross over. They made it! By this time his father was shocked. Is that what they are teaching you in Sunday School? Well no, not exactly, Danny admitted. But if I told it to you the same way they told it to us, you’d never believe it dad. As hard as it may be for some to believe that God works miracles and over the years have sought to explain away what happened, the actual story of Israel’s crossing of the Red Sea goes like this: “After leaving Sukkoth they camped at Etham on the edge of the desert. -

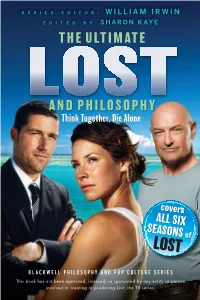

The Ultimate and Philosophy

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN What are the metaphysics of time travel? EDITED BY SHARON KAYE How can Hurley exist in two places at the same time? THE ULTIMATE What does it mean for something to be possibly true in the fl ash-sideways universe? Does Jack have a moral obligation to his father? THE ULTIMATE What is the Tao of John Locke? Dude. So there’s, like, this island? And a bunch of us were on Oceanic fl ight 815 and we crashed on it. I kinda thought it was my fault, because of those numbers. I thought they were bad luck. We’ve seen the craziest things here, like a polar bear and a Smoke Monster, and we traveled through time back to the 1970s. And we met the Dharma dudes. Arzt even blew himself up. For a long time, I thought I was crazy. But now, I think it might have been destiny. The island’s made me question a lot of things. Like, why is it that Locke and Desmond have the same names as real philosophers? Why do so many of us have AND PHILOSOPHY trouble with our dads? Did Jack have a choice in becoming our leader? And what’s up Think Together, Die Alone with Vincent? I mean, he’s gotta be more than just a dog, right? I dunno. We’ve all felt pretty lost. I just hope we can trust Jacob, otherwise . whoa. With its sixth-season series fi nale, Lost did more than end its run as one of the most AND PHILOSOPHY talked-about TV programs of all time; it left in its wake a complex labyrinth of philosophical questions and issues to be explored. -

Nature on Trial: the Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 10 Number 10 Civilizations East and West: A Article 7 Memorial Volume for Benjamin Nelson 1-1-1985 Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg E. V. Walter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Walter, E. V. (1985) "Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 10 : No. 10 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol10/iss10/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Walter: Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg 5. Nature on Trial: The Case of the Rooster That Laid an Egg E. V. Walter In 1474, a chicken passing for a rooster laid an egg, and was prosecuted by law in the city of Basel. Now, we are inclined to dismiss the event as fowl play, but in those days lusus naturae was no joke. The animal was sentenced in a solemn judicial proceeding and condemned to be burned alive "for the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg." The execution took place "with as great solemnity as would have been observed in consigning a heretic to the flames, and was witnessed by an immense crowd of townsmen and peasants." 1 The same kind of prosecution took place in Switzerland again as late as 1730. -

The Challenge and Promise of Using

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: The Challenge and Promise of Using Community Policing Strategies to Prevent Violent Extremism: A Call for Community Partnerships with Law Enforcement to Enhance Public Safety, Final Report Author(s): David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Jessica Toliver, Elizabeth Miller Document No.: 249674 Date Received: January 2016 Award Number: 2012-ZA-BX-0002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. THE CHALLENGE AND PROMISE OF USING COMMUNITY POLICING STRATEGIES TO PREVENT VIOLENT EXTREMISM A Call for Community Partnerships with Law Enforcement to Enhance Public Safety David Schanzer Charles Kurzman Jessica Toliver Elizabeth Miller Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University JANUARY 2016 THE CHALLENGE AND PROMISE OF USING COMMUNITY POLICING STRATEGIES TO PREVENT VIOLENT EXTREMISM A Call for Community Partnerships with Law Enforcement to Enhance Public Safety This project was supported by Award No. 2012-ZA-BX-0002, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.