What Is the Art Law on Authenticating Works by Old Masters – Artnet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pear-Shaped Salvator Mundi Things Have Gone Very Badly Pear-Shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi

AiA Art News-service The pear-shaped Salvator Mundi Things have gone very badly pear-shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. It took thirteen years to discover from whom and where the now much-restored painting had been bought in 2005. And it has now taken a full year for admission to emerge that the most expensive painting in the world dare not show its face; that this painting has been in hiding since sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 for $450 million. Further, key supporters of the picture are now falling out and moves may be afoot to condemn the restoration in order to protect the controversial Leonardo ascription. Above, Fig. 1: the Salvator Mundi in 2008 when part-restored and about to be taken by one of the dealer-owners, Robert Simon (featured) to the National Gallery, London, for a confidential viewing by a select group of Leonardo experts. Above, Fig. 2: The Salvator Mundi, as it appeared when sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017. THE SECOND SALVATOR MUNDI MYSTERY The New York arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum (aka CultureGrrl) has performed great service by “Joining the many reporters who have tried to learn about the painting’s current status”. Rosenbaum lodged a pile of awkwardly direct inquiries; gained a remarkably frank and detailed response from the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and drew a thunderous collection of non-disclosures from everyone else. A full year after the most expensive painting in the world was sold, no one will say where it has been/is or when, if ever, it might next be seen. -

Episode 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights

EpisodE 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights Caravaggio’s painting contains a lesson to the viewer about the transience of youth, the perils of sensual pleasure, and the precariousness of life. Questions to Consider 1. How do you react to the painting? Does your impression change after the first glance? 2. What elements of the painting give it a sense of intimacy? 3. Do you share Januszczak’s sympathies with the lizard, rather than the boy? Why or why not? Other works Featured Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607-1610), Caravaggio Young Bacchus (1593), Caravaggio The Fortune Teller (ca. 1595), Caravaggio The Cardsharps (ca. 1594), Caravaggio The Taking of Christ (1602), Caravaggio The Lute Player (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Contarelli Chapel paintings, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi: The Calling of St. Matthew, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew, The Inspiration of St. Matthew (1597-1602), Caravaggio The Beheading of St. John the Baptist (1608), Caravaggio The Sacrifice of Isaac (1601-02), Caravaggio David (1609-10), Caravaggio Bacchus (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Boy with a Fruit Basket (1593), Caravaggio St. Jerome (1605-1606), Caravaggio ca. 1595-1600 (oil on canvas) National Gallery, London A Table Laden with Flowers and Fruit (ca. 1600-10), Master of the Hartford Still-Life 9 EPTAS_booklet_2_20b.indd 10-11 2/20/09 5:58:46 PM EpisodE 6 Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci Highlights A robbery and attempted forgery in 1911 helped propel Mona Lisa to its position as the most famous painting in the world. Questions to Consider 1. -

ARTS 5306 Crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art History Fall 2020

ARTS 5306 crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art HIstory fall 2020 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR 11:00 – 12:00, 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 2:00 – 3:15 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex and remotely. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 1303 and 1304 (Art History I and II) or the equivalent in history. Text: Not required. The artists and most artworks come from Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one. Objectives: .1a Broaden your interest in Baroque art in Europe by examining artworks by artists we studied in Art History II and artists perhaps new to you. .1b Understand the social, political and religious context of the art. .2 Identify major and typical works by leading artists, title and country of artist’s origin and terms (id quizzes). .3 Short essays on artists & works of art (midterm and end-term essay exams) .4 Evidence, analysis and argument: read an article and discuss the author’s thesis, main points and evidence with a small group of classmates. -

Mario Minniti Young Gallants

Young Gallants 1) Boy Peeling Fruit 1592 2) The Cardsharps 1594 3) Fortune-Teller 1594 4) David with the Head 5) David with the Head of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Mario Minniti 1) Fortune-Teller 1597–98 2) Calling of Saint 3) Musicians 1595 4) Lute Player 1596 Matthew 1599-00 5) Lute Player 1600 6) Boy with a Basket of 7) Boy Bitten by a Lizard 8) Boy Bitten by a Lizard Fruit 1593 1593 1600 9) Bacchus 1597-8 10) Supper at Emmaus 1601 Men-1 Cecco Boneri 1) Conversion of Saint 2) Victorious Cupid 1601-2 3) Saint Matthew and the 4) John the Baptist 1602 5) David and Goliath 1605 Paul 1600–1 Angel, 1602 6) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis, 1609 K 1) Martyrdom of Saint 2) Conversion of Saint Paul 3) Saint John the Baptist at Self portraits Matthew 1599-1600 1600-1 the Source 1608 1) Musicians 1595 2) Bacchus1593 3) Medusa 1597 4) Martyrdom of Saint Matthew 1599-1600 5) Judith Beheading 6) David and Goliath 7) David with the Head 8) David with the Head 9) Ottavia Leoni, 1621-5 Holofernes 1598 1605 of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Men 2 Women Fillide Melandroni 1) Portrait of Fillide 1598 2) Judith Beheading 3) Conversion of Mary Holoferne 1598 Magdalen 1599 4) Saint Catherine 5) Death of the 6) Magdalen in of Alexandria 1599 Virgin 1605 Ecstasy 1610 A 1) Fortune teller 1594 2) Fortune teller 1597-8 B 1) Madonna of 2) Madonna dei Loreto 1603–4 Palafrenieri 1606 Women 1 C 1) Seven Acts of Mercy 2) Holy Family 1605 3) Adoration of the 4) Nativity with Saints Lawrence 1606 Shepherds -

Leonardo Da Vinci's

National Gallery Technical Bulletin volume 32 Leonardo da Vinci: Pupil, Painter and Master National Gallery Company London Distributed by Yale University Press TB32 prelims exLP 10.8.indd 1 12/08/2011 14:40 This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2011 All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are © The National Gallery, London unless credited otherwise below. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including BRISTOL photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without © Photo The National Gallery, London / By Permission of Bristol City prior permission in writing from the publisher. Museum & Art Gallery: fig. 1, p. 79. Articles published online on the National Gallery website FLORENCE may be downloaded for private study only. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence © Galleria deg li Uffizi, Florence / The Bridgeman Art Library: fig. 29, First published in Great Britain in 2011 by p. 100; fig. 32, p. 102. © Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale National Gallery Company Limited Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street Culturali: fig. 1, p. 5; fig. 10, p. 11; fig. 13, p. 12; fig. 19, p. 14. © London WC2H 7HH Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali / Photo Scala, www.nationalgallery. org.uk Florence: fig. 7, p. -

Christie's Has Announced That It Will Auction on November 15 the Only Painting by Leonardo Da Vinci in Private Hands, Salavato

Christie’s has announced that it will auction on November 15 the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in private hands, Salavator Mundi. Here is an excerpt on that painting from Walter Isaacson’s new biography, Leonardo da Vinci, published in October. SALVATOR MUNDI In 2011 a newly rediscovered work by Leonardo surprised the art world. It was a painting known as Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World), which showed Jesus gesturing in blessing with his right hand while holding a solid crystal orb in his left. The Salvator Mundi motif, which features Christ with an orb topped by a cross, known as a globus cruciger, had become very popular by the early 1500s, especially among northern European painters. Leonardo’s version contains some of his distinctive features: a figure that manages to be at once both reassuring and unsettling, a mysterious straight-on stare, an elusive smile, cascading curls, and sfumato softness. Before the painting was authenticated, there was historic evidence that one like it existed. In the inventory of Salai’s estate was a paint- ing of “Christ in the Manner of God the Father.” Such a piece was catalogued in the collections of the English king Charles I, who was beheaded in 1649, and also Charles II, who restored the monarchy Salvator Mundi. 5P_Isaacson_daVinci_EG.indd 330 8/7/17 3:35 PM in 1660. The historical trail of Leonardo’s version was lost after the painting passed from Charles II to the Duke of Buckingham, whose son sold it in 1763. But a historic reference remained: the widow of Charles I had commissioned Wenceslaus Hollar to make an etching of the painting. -

Salvator Mundi Steven J. Frank ([email protected])

A Neural Network Looks at Leonardo’s(?) Salvator Mundi Steven J. Frank ([email protected]) and Andrea M. Frank ([email protected])1 Abstract: We use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to analyze authorship questions surrounding the works of Leonardo da Vinci in particular, Salvator Mundi, the world’s most expensive painting and among the most controversial. Trained on the works of an artist under study and visually comparable works of other artists, our system can identify likely forgeries and shed light on attribution controversies. Leonardo’s few extant paintings test the limits of our system and require corroborative techniques of testing and analysis. Introduction The paintings of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) represent a particularly challenging body of work for any attribution effort, human or computational. Exalted as the canonical Renaissance genius and polymath, Leonardo’s imagination and drafting skills brought extraordinary success to his many endeavors from painting, sculpture, and drawing to astronomy, botany, and engineering. His pursuit of perfection ensured the great quality, but also the small quantity, of his finished paintings. Experts have identified fewer than 20 attributable in whole or in large part to him. For the connoisseur or scholar, this narrow body of work severely restricts analysis based on signature stylistic expressions or working methods (Berenson, 1952). For automated analysis using data-hungry convolutional neural networks (CNNs), this paucity of images tests the limits of a “deep learning” methodology. Our approach to analysis is based on the concept of image entropy, which corresponds roughly to visual diversity. While simple geometric shapes have low image entropy, that of a typical painting is dramatically higher. -

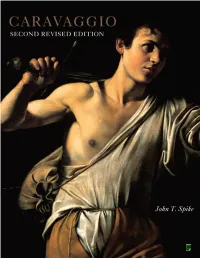

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Technical Bulletin Has Been Supported National Gallery Technical Bulletin by Mrs Charles Wrightsman Volume 36 Titian’S Painting Technique from 1540

This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been supported National Gallery Technical Bulletin by Mrs Charles Wrightsman volume 36 Titian’s Painting Technique from 1540 Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2015 All images © The National Gallery, London, unless credited All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted otherwise below. in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including CAMBRIDGE photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: 51, 52. prior permission in writing from the publisher. CINCINNATI, OHIO Articles published online on the National Gallery website © Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio / Bridgeman Images: 3, 10. may be downloaded for private study only. DRESDEN Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden First published in Great Britain in 2015 by © Photo Scala, Florence/bpk, Bildagnetur für Kunst, Kultur und National Gallery Company Limited Geschichte, Berlin: 16, 17. St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street London WC2H 7HH EDINBURGH Scottish National Gallery © National Galleries of Scotland, photography by John McKenzie: 250–5. www.nationalgallery.co.uk FLORENCE British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Galleria degli uffizi, Florence A catalogue record is available from the British Library. © Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali: 12. ISBN: 978 1 85709 593 7 Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence © Photo Scala, ISSN: 0140 7430 Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali: 45. 1040521 LONDON Apsley House © Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust: 107. Publisher: Jan Green Project Manager: Claire Young © The Trustees of The British Museum: 98. -

Guercino: Mind to Paper/Julian Brooks with the Assistance of Nathaniel E

GUERCINO MIND TO PAPER GUERCINO MIND TO PAPER Julian Brooks with the assistance of Nathaniel E. Silver The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Front and back covers: Guercino. Details from The Assassination © 2006 J. Paul Getty Trust ofAmnon (cat. no. 14), 1628. London, Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery This catalogue was published to accompany the exhibition Guercino:Mind to Paper, held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 17,2006, to January 21,2007, and at the Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, February 22 Frontispiece: Guercino. Detail from Study of a Seated Young Man to May 13,2007. (cat. no. 2), ca. 1619. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum Pages 18—ic>: Guercino. Detail from Landscape with a View of a Getty Publications Fortified Port (cat. no. 22), ca. 1635. Los Angeles, J. Paul 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Getty Museum Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Patrick E. Pardo, Project Editor Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Copy Editor Catherine Lorenz, Designer Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator Typesetting by Diane Franco Printed by The Studley Press, Dalton, Massachusetts All works are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise indicated. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brooks, Julian, 1969- Guercino: mind to paper/Julian Brooks with the assistance of Nathaniel E. Silver, p. cm. "This catalogue was published to accompany the exhibition 'Guercino: mind to paper' held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 17,2006, to January 21,2007." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-89236-862-4 (pbk.) ISBN-io: 0-89236-862-4 (pbk.) i. -

Fitz Henry Lane's Series Paintings of Brace's Rock: Meaning and Technique

Fitz Henry Lane’s Series Paintings of Brace’s Rock: Meaning and Technique FITZ HENRY LANE’S SERIES PAINTINGS OF BRACE’S ROCK: MEANING AND TECHNIQUE A report concerning the relationship of Lane’s painting series, Brace’s Rock Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA (CAM) National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (NGA) Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago (TFAA) By H. Travers Newton, Jr., Consultant, Painting Conservation Studio, Cleveland Museum of Art Based on collaborative research with Marcia Steele, Chief Conservator, Cleveland Museum of Art Prepared for Elizabeth Kennedy, Curator of Collection, edited by Peter John Brownlee, Associate Curator, with the assistance of Naomi H. Slipp, Curatorial Intern, Terra Foundation for American Art April, 2010 ©2010 H. Travers Newton, Jr. 1 Table of Contents Project Introduction and Summary, 3 Part One: Review of the Literature I. Historical Background of Lane’s Images of Brace’s Rock, 4 II. Thematic Inspirations, Interpretations and Precedents: 1. Shipwrecks, 6 2. Nineteenth-Century Panorama Drawings and Paintings in the United States, 12 3. Influence of Thomas Doughty’s Nahant Beach Series, 14 4. Influence of Thomas Chambers, 16 5. Possible European Influences: Dutch Landscapes, 17 6. British Influences: John Ruskin and the Depiction of Rock Formations, 17 7. German and Danish Influences: Caspar David Friedrich and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, 20 Part Two: New Conservation Research on the Brace’s Rock Series, 21 III. Comparison of National Gallery of Art and Cape Ann Museum Versions of Brace’s Rock 1. Relationship of the Field Sketch to the Paintings: The Setting, 22 2. Absence of Reflections in Lane’s Drawings, 24 3. -

The Maturing of a Genius: 1485–1506

282 the maturing of a genius: 1485–1506 pleated bodice of Christ’s figure in the Salvator Mundi (Windsor, RL 12524 and 12525; pls. 7.38, 7.39). These studies date to 1500–5. Their style and technique of “red on red” (red chalk on ocher prepared paper) conform to those of the drawings for the Madonna of the Yarnwinder of about 1504, and the Louvre Virgin and Child with St. Anne begun about 1507–8 but, it will be remembered, this is also a medium that Leonardo explored in the studies for the apostles of the Last Supper in the 1490s.210 The purpose of the “red on red” technique was to create a rich middle base tone on the paper, so that the forms of the figure and ground were in the same chromatic relationship, for a soft, relief-like effect (see Chapter 4). While Leonardo may have bristled with impatience at having to produce a composition within the rigorous constraints of the traditional Salvator Mundi’s imagery, one can envision his imagination breaking free and delighting in the designs of artful complexity for Christ’s draperies. The finer of the two drapery studies for the Savior, the monumental design for his left sleeve (Windsor, RL 12524; pl. 7.38), exhibits left-handed hatching, discernible throughout the design, in what little of the strokes was left unrubbed within the passages of exquisite sfumato rendering.211 The artist used here a chalk stick of some- what rounded tip to produce softer lines, and worked up the modeling to achieve a great density of medium in the deep shadows.