The Listening Post Issue 65—Winter 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 217% to SEK 396 MILLION

THQ NORDIC AB (PUBL) REG NO.: 556582-6558 EXTENDED FINANCIAL YEAR REPORT • 1 JAN 2018 – 31 MAR 2019 OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 217% to SEK 396 MILLION JANUARY–MARCH 2019 JANUARY 2018–MARCH 2019, 15 MONTHS (Compared to January–March 2018) (Compared to full year 2017) > Net sales increased 158% to SEK 1,630.5 m > Net sales increased to SEK 5,754.1 m (507.5). (632.9). > EBITDA increased to SEK 1,592.6 m (272.6), > EBITDA increased 174% to SEK 618.6 m (225.9), corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 28%. corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 38%. > Operational EBIT increased to SEK 897.1 m > Operational EBIT increased 217% to SEK 395.9 m (202.3) corresponding to an Operational EBIT (124.9) corresponding to an Operational EBIT margin of 16%. margin of 24%. > Cash flow from operating activities amounted > Cash flow from operating activities amounted to SEK 1,356.4 m (179.1). to SEK 777.2 m (699.8). > Earnings per share was SEK 4.68 (1.88). > Earnings per share was SEK 1.10 (1.02). > As of 31 March 2019, cash and cash equivalents were SEK 2,929.1 m. Available cash including credit facilities was SEK 4,521.1 m. KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS, Jan-Mar Jan-Mar Jan 2018- Jan-Dec GROUP 2019 2018 Mar 2019 2017 Net sales, SEK m 1,630.5 632.9 5,754.1 507.5 EBITDA, SEK m 618.6 225.9 1,592.6 272.6 Operational EBIT, SEK m 395.9 124.9 897.1 202.3 EBIT, SEK m 172.0 107.3 574.6 188.2 Profit after tax , SEK m 103.0 81.1 396.8 139.2 Cash flow from operating activities, SEK m 777.2 699.8 1,356.4 179.1 Sales growth, % 158 673 1,034 68 EBITDA margin, % 38 36 28 54 Operational EBIT margin, % 24 20 16 40 Throughout this report, the extended financial year 1 January 2018 – 31 March 2019 is compared with the financial year 1 January – 31 December 2017. -

First Battle of the Marne After Invading Belgium and North-Eastern France

First Battle of the Marne After invading Belgium and north-eastern France during the Battle of Frontiers, the German army had reached within 30 miles of Paris. Their progress had been rapid, giving the French little time to regroup. The First Battle of the Marne was fought between September 6th through the 12th in 1914, with the German advance being brought to a halt, and a stalemate and trench warfare being established as the norm. As the German armies neared Paris, the French capital prepared itself for a siege. The defending French and British forces were at the point of exhaustion, having retreated continuously for 10-12 days under repeated German attack until they had reached the south of the River Marne. Nevertheless, the German forces were close to achieving a breakthrough against the French forces, and were only saved on the 7th of September by the aid of 6,000 French reserve infantry troops brought in from Paris by a convoy of taxi cabs, 600 cabs in all. On September 9th, the German armies began a retreat ordered by the German Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke. Moltke feared an Allied breakthrough, plagued by poor communication from his lines at the Marne. The retreating armies were pursued by the French and British, although the pace of the Allied advance was slow - a mere 12 miles in one day. The German armies ceased their withdrawal after 40 miles at a point north of the River Aisne, where the First and Second Armies dug in, preparing trenches that were to last for several years. -

Two Canine Heads Are Better Than One in PHOGS!

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES Issue 36 £3 wfmag.cc HoundedHounded OutOut Two canine heads are better than one in PHOGS! CARDS AND DICE YOUR STORY LOSS AND FOUND The growing influence Code an FMV Making personal games on video game design adventure game that deal with grief get in the 4K Ultra HD UltraWideColor Adaptive Sync Overwatch and the return of the trolls e often talk about ways to punish stalwarts who remain have resorted to trolling out of “ players who are behaving poorly, sheer boredom. and it’s not very exciting to a lot of Blizzard has long emphasised the motto “play W us. I think, more often than not, nice, play fair” among its core values, and Overwatch’s players are behaving in awesome ways in Overwatch, endorsement system seemed to embrace this ethos. and we just don’t recognise them enough.” JESS Why has it failed to rein in a community increasingly Designer Jeff Kaplan offered this rosy take on the MORRISSETTE intent on acting out? I argue that Overwatch’s Overwatch community in 2018 as he introduced the Jess Morrissette is a endorsements created a form of performative game’s new endorsement system, intended to reward professor of Political sportsmanship. It’s the promise of extrinsic rewards players for sportsmanship, teamwork, and leadership Science at Marshall – rather than an intrinsic sense of fair play – that on the virtual battlefields of Blizzard’s popular shooter. University, where motivates players to mimic behaviours associated with he studies games After matches, players could now vote to endorse one and the politics of good sportsmanship. -

Battlefields Trip 'Ypres' and 'The Somme'

Battlefields Trip ‘Ypres’ and ‘The Somme’ Name: _______________________________________________ 1 My Name is: My Link Teacher / Anglia guide My roommates are: Belgium France (Comment on the things that you see and (Comment on the things that you see and experience: Language, houses jobs etc) experience: Language, houses jobs etc) 2 Contents Page: N.B. Shadowed boxes i.e. Indicate an opportunity for you to enhance your experience of the trip, it isn’t schoolwork but please attempt the task so that you get the most from the visit. It’s nice to look back at a future time and reflect on your experiences. Itinerary (may be subject to change) (* = Activity page) 3 Glossary: During this visit you will encounter many words, some of which will be new to you, so to make sure that you get the most from your visit, some are listed below: Flanders = name given to the flat land across N. France and Belgium Enfilade = when soldiers are shot/ attacked at from the side (flank). Salient = a “bulge” which sticks out into enemy land Artillery = large cannons or “guns” Front line = where opposing armies meet No-mans land = space between opposing armies Passchendaele = A village name, also given to the third Battle of Ypres “Wipers” = a nickname given to Ypres by British soldiers Division = a military term approximately 10,000 fighting men i.e. 29th Division- all armies were organised into Divisions. WARNING!! Over 90 years after the war unexploded munitions are still ploughed up in a dangerous, unstable condition. All such items must be treated with extreme caution and avoided. -

Bachelor Thesis

BACHELOR THESIS Mr. Justin Zwack Characteristics of a Design Template for Modern Boss Encounters in Action Games and its Adaptation to the RTS Genre. An Analysis of Boss Design and a Prototypical Implementation in “Iron Harvest”. Bremen, 2018 Faculty Applied Computer Sciences & Biosciences BACHELOR THESIS Characteristics of a Design Template for Modern Boss Encounters in Action Games and its Adaptation to the RTS Genre. An Analysis of Boss Design and a Prototypical Implementation in “Iron Harvest”. author: Mr. Justin Zwack course of studies: Media Informatics and Interactive Entertainment seminar group: MI14w1-B first examiner: Mr. Professor Alexander Marbach second examiner: Ms. Sieglinde Klimant submission: Bremen, 2018 Confidentiality clause: This submitted bachelor thesis with the title “Characteristics of a Design Template for Modern Boss Encounters in Action Games and its Adaptation to the RTS Genre. An Analysis of Boss Design and a Prototypical Implementation in ‘Iron Harvest’.” contains confidential information and data of KING Art GmbH. This work may only be made available to the first and second reviewers and authorized members of the board of examiners. Any publication and duplication of this work - even in part - is prohibited. An inspection of this work by third parties requires the expressed permission of the author and company. Bibliography Zwack, Justin Characteristics of a Design Template for Modern Boss Encounters in Action Games and its Adaptation to the RTS Genre. An Analysis of Boss Design and a Prototypical Implementation in “Iron Harvest”. 86 pages, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Faculty Applied Computer Sciences & Biosciences, bachelor thesis, 2018 Abstract In many action video game franchises, bosses are an essential part of their core expe- rience. -

The Secret Sauce of Indie Games

EVERY ISSUE INCL. COMPANY INDEX 03-04/2017 € 6,90 OFFICIAL PARTNER OF DESIGN BUSINESS ART TECHNOLOGY THE SECRET SAUCE OF FEATURING NDIEThe Dwarves INDIE GAMES Can‘t Drive This I Cubiverse Savior GAMES GREENLIGHT BEST PRACTICE: TIPS TO NOT GET LOST ON STEAM LEVEL ARCHITECTURE CASE STUDY GREENLIGHT POST MORTEM INTERVIEW WITH JASON RUBIN HOW THE LEVEL DESIGN AFFECTS HOW WINCARS RACER GOT OCULUS‘ HEAD OF CONTENT ABOUT THE DIFFICULTY LEVEL GREENLIT WITHIN JUST 16 DAYS THE LAUNCH AND FUTURE OF VR Register by February 25 to save up to $300 gdconf.com Join 27,000 game developers at the world’s largest professional game industry event. Learn from experts in 500 sessions covering tracks that include: Advocacy Monetization Audio Production & Team Management Business & Marketing Programming Design Visual Arts Plus more than 50 VR sessions! NEW YEAR, NEW GAMES, NEW BEGINNINGS! is about 1.5 the world on edge with never-ending ques- months old, tionable decisions. Recently, Trump’s Muslim Dirk Gooding and just ban for entry into the United States caused Editor-in-Chief of Making Games Magazin within these mass protests and numerous reactions by few weeks it the international games industry which is seemed that negatively affected by such a ban in a not-to- 2017one news followed the other. The first big be underestimated way. Will 2017 be another conferences and events like Global Game troublesome year? Before Christmas, we Jam, PAX South, GIST, Casual Connect or asked acclaimed experts and minds of the White Nights in Prague are over, but the German games industry to name their tops planning for the next events like QUO and flops, desires and predictions – for both Nico Balletta VADIS and our very own Making Games last and this year. -

Eye Not Only Made Sickle Possible but Elevated the Game Profes‐ Sionally and Artistically. Keep an Eye out Fo

eye not only made Sickle possible but elevated the game profes‐ Sickle: A Fan‐Made Scythe Megagame sionally and artistically. Keep an eye out for his upcoming mega‐ game design, Deephaven, which will be play tested in Minnesota before premiering at GenCon 2019. This event was created to be non‐profit educational event. Even though non‐profit educational events are already granted ex‐ treme leniency in the use of copyrighted art and materials, Min‐ nesota Megagames attempted to get permission from Jakub Ró‐ żalski and Stonemaier Games. While the extremely busy Jakub Różalski did not respond to repeated outreach attempts, Stonemaier Games did encourage the project over Facebook and in person during brief encounters at board game conventions. While we’re uncertain as to whether anyone at Stonemaier Games ever fully conceived as to the scope of this event, we wholeheartedly thank them for their support. According to the lawyers we’ve talked to, we’re currently not breaking any laws, but if there are any laws we are breaking, please let us know. Peter and Trenton would like to thank all the volunteer modera‐ tors for helping make this event possible. We owe you a beer. Join 40+ other players to fight, negotiate, and harness powerful new technologies as prominent political factions, scientists, and Thanks to The Con of the North for providing a venue for this industrialists involved in the power struggles of Eastern Europa! event. At the center of these power struggles is the mysterious Factory. Lastly, we’d like to thank the Players for indulging this passion Originally constructed by Nikolai Tesla, the Factory produced project and celebrating the 1920+ universe with us. -

Explo Re W W I O Utside the C Lassro

Explore WWI outside the classroom in FLANDERS FIELDS - Explore with your class WWI 1 in FIELDS FLANDERS is booklet brings together inspiring initiatives in various counties and cities around the First World War. Use this guide to create your own WWI trip and wander o the beaten track. 2 - Explore with your class WWI Explore WWI outside the classroom WWI the outside Explore PREFACE This guide, produced by Visit Flanders in partnership with the Province of West Flanders, aims to help tour operators and teachers organise field trips to WWI sites for English-language primary and secondary school pupils. The guide provides dozens of ideas for enriching the experience for the children. You will find the most famous WWI memorials on the Western Front in Flanders listed in these pages but also many other locations in Flanders Fields and the wider area that tell the story of occupied Belgium. In other words, besides the ones we have all heard of, there are many smaller sites worthy of a visit. Moreover, this guide covers tips for visiting a memorial, teaching resources for preparing a trip, interesting websites, accommodation, alternative transport, how to organise a multi-day trip, and information on the cultural programme GoneWest, including the unique sculpture project ‘ComingWorldRememberMe’. We profoundly hope this information will inspire and help you to schedule trips to Flanders Fields with your school groups. They are most welcome – we consider it our duty to pass on the legacy of WWI by offering them a quality educational and visitor experience. 5 - Geert Bourgeois Minister-President of Flanders Flemish Minister for Foreign Policy and Immovable Heritage Myriam Vanlerberghe Commissioner for Culture, Province of West Flanders Explore with your class WWI PRACTICAL INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS This guide provides you with an overview of the educational facilities for each 9 Introduction site. -

The German Games Industry 2019

The German games industry 2019 Insights, facts and reports Anno 1800, the latest instalment Editorial 4 of the renowned strategy series, is being developed in close connection Investing in the German games market 6 with the loyal Anno community. Ten good reasons for investing in the German market Federal budget includes 50 million euros for games funding for the first time Associations, networks and funding 14 German market for digital games: 16 facts and figures Germany’s developer landscape 26 Job market situation and education 30 opportunities Gaming studios and companies 32 That’s what they said: German devs 48 and industry experts about Germany’s gaming industry Esports in Germany 50 gamescom: celebrate the games 56 Education register 60 Association register 64 Company register 66 Contents 3 Dear Readers, Some 520 companies in Germany are active in the development and marketing of games, providing jobs Germany is one of the most important markets for for over 11,000 people. Universities in many large computer and video games worldwide. No European German cities also train new talent for all major areas country generates higher sales with games and the of the games industry. Germany also plays a special associated hardware. Germany’s benefits as a business role in the esports segment: some of the world’s largest location include its geographical position in the heart tournaments, the ESL One tournaments, take place of Europe and its excellent infrastructure, as well as its here. And the ESL itself, one of the most important membership in the EU and the uninhibited exchange it organisers of esports tournaments and leagues in the therefore enjoys with over half a billion people on the world, is headquartered in Germany. -

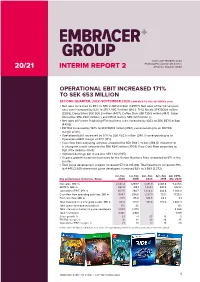

20/21 Interim Report 2 Reg No

JULY–SEPTEMBER 2020 EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) 20/21 INTERIM REPORT 2 REG NO. 556582-6558 OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 171% TO SEK 653 MILLION SECOND QUARTER, JULY–SEPTEMBER 2020 (COMPARED TO JULY–SEPTEMBER 2019) > Net sales increased by 89% to SEK 2,383.2 million (1,259.7). Net sales of the Games busi- ness area increased by 83% to SEK 1,495.4 million (816.1). THQ Nordic SEK 566.9 million (329.6), Deep Silver SEK 506.8 million (441.7), Coffee Stain SEK 129.9 million (44.7), Saber Interactive SEK 259.1 million (-) and DECA Games SEK 32.7 million (-). > Net sales of Partner Publishing/Film business area increased by 100% to SEK 887.8 million (443.6). > EBITDA increased by 132% to SEK 969.0 million (418.1), corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 41%. > Operational EBIT increased by 171% to SEK 652.5 million (240.7) corresponding to an Operational EBIT margin of 27% (19%). > Cash flow from operating activities amounted to SEK 804.7 million (284.8). Investments in intangible assets amounted to SEK 484.1 million (391.9). Free Cash Flow amounted to SEK 311.5 million (–115.8). > Adjusted earnings per share was SEK 1.80 (0.65). > Organic growth in constant currency for the Games Business Area amounted to 61% in the quarter. > Total game development projects increased 57% to 135 (86). Total headcount increased 49% to 4,445 (2,981) where total game developers increased 58% to 3,593 (2,272). Jul–Sep Jul–Sep Apr–Sep Apr–Sep Apr 2019– Key performance indicators, Group 2020 2019 2020 2019 Mar 2020 Net sales, SEK m 2,383.2 1,259.7 4,451.9 2,401.8 5,249.4 -

Feb. 2 - 8, 2021 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……

Weekly Media Report – Feb. 2 - 8, 2021 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… TECHNOLOGICAL LEADERSHIP: 1. Technological Leadership: Combing Research and Education for Advantage at Sea (USNI Feb 21) … NPS President retired Vice Adm. Ann E. Rondeau, US Navy We stand at a critical inflection point. U.S. national security must contend with increasing great power competition (GPC), which is fundamentally an innovation race—one well contested by our near-peer rivals. While technological change is inevitable, the rapidly emerging integration of computational power with its human masters, the so-called Cognitive Age is poised to create unprecedented national security challenges, and at a pace measured in months and not years. RESEARCH: 2. Xerox and Naval Postgraduate School Announce Collaboration to Advance Solutions with 3D Printing Research (NPS.edu 3 Feb 21) … NPS Office of University Communications (Navy.mil 3 Feb 21) … NPS Office of University Communications (Business Wire 3 Feb 21) (Odessa America 3 Feb 21) (TCT Magazine 3 Feb 21) … Sam Davies (3D Printing Media 4 Feb 21) … Davide Sher (Metal AM 4 Feb 21) (ExecutiveBiz 4 Feb 21) … Nichols Martin (West Fair Online 5 Feb 21) … Phil Hall Xerox and the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) announced today a strategic collaboration focused on advancing additive manufacturing research, specifically 3D printing, which has the potential to dramatically transform the way the military supplies its forward-deployed forces. 3. This huge Xerox printer can create metal parts for the US Navy (Popular Science 3 Feb 21) … Rob Verger Xerox’s new printer is 9 feet wide, 7 feet tall, and reaches an internal temperature of more than 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit. -

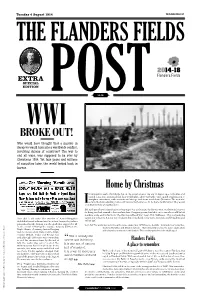

The Flanders Fields Post the Flanders Fields

Tuesday 4 August 1914 THE FLANDERS FIELDS POST THE FLANDERS FIELDS EXTRA SPECIAL EDITION POST14-18 WWI BROKE OUT! Who would have thought that a murder in Sarajevo would turn into a worldwide conflict, involving dozens of countries? The war to end all wars, was supposed to be over by Christmas 1914. Yet four years and millions of casualties later, the world looked back in horror. Home by Christmas n hindsight it seems improbable but, at the actual onset of the war in August 1914, both allies and central states were convinced that they would fight a short war battle - just a quick confrontation to straighten out matters, settle accounts and then go back home to celebrate Christmas. The men who went to the front, whistling, believed it and said to their wives, I’ll be home by Christmas! They would Isoon find out how wrong they were. Did each party have its justifications for going to war at the start? As the war went on, the initial reasons for being involved seemed to become less clear. The great powers battled it out to see who would be left standing at the end. In his book ‘The War that will end War’ (1914), H.G. Wells says, “This is already the How did it all start? The murder of Austro-Hungarian vastest war in history. It is war not of nations but of mankind. It is a war to exorcise a world-madness and Archduke Franz-Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo by Serbian end an age.” nationalist Gavrilo Princip was the spark that triggered it all.