The Right Brain in Poe's Creative Process by Mark Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Raven-Abridged.Pdf

The Raven Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately raven of the saintly days of yore. By Edgar Allen Poe Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door - Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary, Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door - Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, Perched, and sat, and nothing more. While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, `'Tis some visitor,' I muttered, `tapping at my chamber door - By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore, Only this, and nothing more.' `Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,' I said, `art sure no craven. Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the nightly shore - Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December, Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!' And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.' Eagerly I wished the morrow; - vainly I had sought to borrow From my books surcease of sorrow - sorrow for the lost Lenore - `Prophet!' said I, `thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil! For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels named Lenore - By that Heaven that bends above us - by that God we both adore - Nameless here for evermore. -

Trauma and the Uncanny in Edgar Allan Poe's “Ligeia” and “The Fall Of

Trauma and the Uncanny in Edgar Allan Poe’s “Ligeia” and “The Fall of the House of Usher” Marita Nadal, Universidad de Zaragoza Abstract As a disorder of memory and time, trauma implies a crisis of representation, of history and truth. It remains in the mind like an intruder or a ghost, foregrounding the disjunction between the present and a primary experience of the past that can never be captured. Like trauma, the uncanny implies haunting, uncertainty, repe- tition, a tension between the known and the unknown, and the intrusive return of the past. Taking the characteristics of these concepts as the point of departure, this paper analyzes Poe’s Gothic tales “Ligeia” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and explores the close relationship between trauma and the uncanny in both of them. Thus the protagonists of these tales experience the desire to know and the fear of doing so—the basic dilemma at the heart of traumatic experience—and are haunted by memories of a remote and repressed past not recoverable by con- scious means but which determines their life in the present. The paper discusses trauma and the uncanny in the light of trauma theory, psychoanalysis, and Gothic criticism, pointing out the centrality of memory and the notion of origins. Keywords trauma, uncanny, Gothic, memory, origins What was it . which lay far within the pupils of my beloved? What was it? I was possessed with a passion to discover. —Edgar Allan Poe, “Ligeia” What was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher? It was a mystery all insoluble. -

The Story Washington-Wilkes

* THE STORY OF WASHINGTON-WILKES * * AMERICAN GUIDE SERIES * ashinglon- COMPILED AND WRITTEN BY WORKERS OF THE WRITERS ' PROGRAM OF THE WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION IN THE STATE OF GEORGIA Illustrated * Sponsored by the Washington City Council THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS ATHENS I 9 4 I FEDERAL WORKS AGENCY JoHN M. CARMODY, Administrator WORK. PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION HowARD O. HuNTER, Commissioner FLORENCE l(ERR, Assistant Commissioner H. E. HARMON, State Adnzinistrator COPYRIGHTED 1941 BY THE WASHINGTON CITY COUNCIL PRINTED IN U.S.A. BY THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED, INCLUDING THE RIGHTS TO REPRODUCE THIS BOOK OR PARTS THEREOF IN ANY FORM. CITY OF WASHINGTON WASHINGTON. GEORGIA W. C. LINDSEY. MAYOR COUNCILMEN F. E. BOLINE.CL'l:RK J,G.ALLEN A. A. JOHNSON UO KRUHBtltt 105'1 NASH 11. P. POPE DR. A. W. SIMPSON We, the Mayor and Council of Washington Georgia, feel that we are fortunate in having an opportunity to sponsor a History and Guide of our town and county through the Georgia Writers' Froject of the Work Projects Adminis• tration of the state. It is a pleasure for us to add a word of appreciation to this little book which will find its way to all parts of our nation, telling in a quaint and simple manner the story of th1s locality which is so rich in history, and carrying glimpses or the beauty of our homes and surroundinBs. We are happy to sponsor this worthwhile work and are grateful to the Georgia Writers' Project for giving Miss Minnie Stonestreet the task of compiling this important volume. -

ANALYSIS “Ligeia” (1838) Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) “With Her Name Drawn Equally out of Ivanhoe and “Christabel,'

ANALYSIS “Ligeia” (1838) Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) “With her name drawn equally out of Ivanhoe and “Christabel,’ Rowena we may fairly assume, is the living incarnation of English Romanticism…or English Transcendental thought cloaked in allegorical trappings. Yet in the narrator’s view, the lady of Tremaine was as destitute of Ligeia’s miraculous insights as of her stupendous learning and oracular gibberish. Conventional and dull, the blonde was simply another of those golden objects overcast by the leaden-grey window. Only in a moment ‘of his mental alienation’ did she seem to the narrator to be a fit ‘successor of the unforgotten Ligeia’; soon he came to loathe her ‘with a hatred belonging more to demon than to man.’ Rowena, in short, symbolizes an impoverished English Romanticism, as yet ‘unspiritualized’ by German cant. Consequently, she represents but a shallow pretense of Romanticism; and—on this point the text is admirably plain—it is a part of Poe’s joke to make her Romantic in nothing save her borrowed name.” Clark Griffith “Poe’s ‘Ligeia’ and the English Romantics” University of Toronto Quarterly 24 (1954) An introductory quotation asserts, contrary to Christianity, that God is “but a great will pervading all things” and that Man can resist death if his will is strong enough. Poe emphasizes this theme by repeating it twice in the story. A narrator not differentiated from Poe meets Ligeia in Germany, where gothic romanticism appealing to Poe’s sensibility was popular. He compares her to a “shadow.” Like other writers, Poe discovered through metaphor the psychological concept defined later by Carl Jung: the shadow represents the repressed self. -

Poe's Paradox of Unity

Jordan Lewis Fall 2017 Poe’s Paradox of Unity A Critical Literary Analysis Written by Jordan Lewis Rice University, Class of 2018 English & Managerial Studies 1 Jordan Lewis Fall 2017 Abstract This essay is an analysis of some of Edgar Allan Poe’s artistic works through the lens of his empirical, but often very pedagogical works. In many ways, his later texts, namely “The Philosophy of Composition” and “Eureka” serve as a guideline upon which to evaluate Poe’s poems. This essay explores the degree to which the “rules” postulated in both Poe’s essay and prose-poem are followed in two of his poems, “The Raven” and “Ulalume.” Consequently, the meaning of “unity” in Poe’s writing is explored, and the degree to which adherence of his own prescribed rules has an effect on creating unity within the poem. I argue that there are two types of unity that embody these poems in different ways: ‘unity of impression’, which Poe defines and discusses in “The Philosophy of Composition,” and ‘perfect unity,’ a term derived from his contemplations in “Eureka.” Through this analysis, we can better understand the subliminal elements that may be at work in these pieces of literature, and the reason that Poe’s works are uniquely known to generate such effects on his readers. 2 Jordan Lewis Fall 2017 Poe’s Paradox of Unity In writing his 1846 work, “The Philosophy of Composition”, Edgar Allan Poe creates an essay that reinforces the readers’ impressions of his most successful poem to date, “The Raven,” as he imagines those impressions are invoked. -

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe 1 Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, 31 Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning, 2 Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore — 32 Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before. 3 While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, 33 "Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice; 4 As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. 34 Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore — 5 "'Tis some visiter," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door — 34 Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;— 6 Only this and nothing more." 36 'Tis the wind and nothing more!" 7 Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; 37 Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, 8 And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. 38 In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore; 9 Eagerly I wished the morrow; — vainly I had sought to borrow 39 Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; 10 From my books surcease of sorrow — sorrow for the lost Lenore — 40 But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door — 11 For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore — 41 Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door — 12 Nameless here for evermore. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1976, Volume 71, Issue No. 3

AKfLAND •AZIN Published Quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society FALL 1976 Vol. 71, No. 3 BOARD OF EDITORS JOSEPH L. ARNOLD, University of Maryland, Baltimore County JEAN BAKER, Goucher College GARY BROWNE, Wayne State University JOSEPH W. COX, Towson State College CURTIS CARROLL DAVIS, Baltimore RICHARD R. DUNCAN, Georgetown University RONALD HOFFMAN, University of Maryland, College Park H. H. WALKER LEWIS, Baltimore EDWARD C. PAPENFUSE, Hall of Records BENJAMIN QUARLES, Morgan State College JOHN B. BOLES, Editor, Towson State College NANCY G. BOLES, Assistant Editor RICHARD J. COX, Manuscripts MARY K. MEYER, Genealogy MARY KATHLEEN THOMSEN, Graphics FORMER EDITORS WILLIAM HAND BROWNE, 1906-1909 LOUIS H. DIELMAN, 1910-1937 JAMES W. FOSTER, 1938-1949, 1950-1951 HARRY AMMON, 1950 FRED SHELLEY, 1951-1955 FRANCIS C. HABER 1955-1958 RICHARD WALSH, 1958-1967 RICHARD R. DUNCAN, 1967-1974 P. WILLIAM FILBY, Director ROMAINE S. SOMERVILLE, Assistant Director The Maryland Historical Magazine is published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201. Contributions and correspondence relating to articles, book reviews, and any other editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor in care of the Society. All contributions should be submitted in duplicate, double-spaced, and consistent with the form out- lined in A Manual of Style (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969). The Maryland Historical Society disclaims responsibility for statements made by contributors. Composed and printed at Waverly Press, Inc., Baltimore, Maryland 21202,. Second-class postage paid at Baltimore, Maryland. © 1976, Maryland Historical Society. 6 0F ^ ^^^f^i"^^lARYLA/ i ^ RECORDS LIBRARY \9T6 00^ 26 HIST NAPOLIS, M^tl^ND Fall 1976 #. -

Early Georgia Magazines Is a Job Well Done

T1 EARLY GEORGIA irst published in 1944, this is a detailed survey of twenty-four o distinguished periodicals published in antebellum Georgia. Flanders shows that literary activity was generally confined to middle Georgia F CO MAGAZINES and often concentrated on themes of religion and morality, early American life, and European adventures. An extensive bibliography and three appendices give a comprehensive list of magazines published during the time, including dates, places of publication, and names of editors and publishers. More than nine hundred footnotes further elaborate on the analysis of backgrounds, local historical events, and information on contributors. "Indeed, it would be difficult to conjure up a query on Georgia's literary magazines that is not answered in Flanders's excellent study. Early Georgia Magazines is a job well done. For his accomplishment, Flanders deserves the admiration of all students of the Old South." South Atlantic Bulletin "Packed with details, lists of representative contents and distributors, and careful details of publication . the work is definitive in its field." American Literature "Has successfully captured much of the richness of human existence . [Flanders's] book becomes in part the story of Georgia life, with now a bit of humor and now pathos as one sees the thorny path trod by the early editors and contributors." Social Forces Bertram Holland Flanders (1892-1979) is also the author of A New Frontier in Education: The Story of the Atlanta Division, University of Georgia. The University of Georgia -

Poe Work Packet

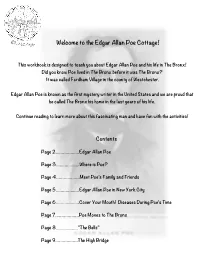

Welcome to the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage! This workbook is designed to teach you about Edgar Allan Poe and his life in The Bronx! Did you know Poe lived in The Bronx before it was The Bronx? It was called Fordham Village in the county of Westchester. Edgar Allan Poe is known as the first mystery writer in the United States and we are proud that he called The Bronx his home in the last years of his life. Continue reading to learn more about this fascinating man and have fun with the activities! Contents Page 2……………….Edgar Allan Poe Page 3……………….Where is Poe? Page 4……………….Meet Poe’s Family and Friends Page 5……………….Edgar Allan Poe in New York City Page 6……………….Cover Your Mouth! Diseases During Poe’s Time Page 7……………….Poe Moves to The Bronx Page 8………………”The Bells” Page 9………………The High Bridge Edgar Poe was born in 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts to actors! He would travel with his mother to shows she performed in. Sadly, she died, but the Allan family took him in and raised him. This is how he took the Allan name. When he grew up he moved around a lot. He lived in Richmond, Virginia, London, England, Baltimore, Maryland, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Boston, Massachusetts, and New York City, New York writing poetry and short stories! He even studied at West Point Military Academy for a time. It was in Baltimore where he met and married his wife Virginia. Virginia and her mother, Maria Clemm, moved to New York City with Edgar. -

James Russell Lowell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Russell Lowell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Russell Lowell(22 February 1819 – 12 August 1891) James Russell Lowell was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He would publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career. Maria White died in 1853, and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854. -

KENTUCKY in AMERICAN LETTERS Volume I by JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND

KENTUCKY IN AMERICAN LETTERS Volume I BY JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND KENTUCKY IN AMERICAN LETTERS JOHN FILSON John Filson, the first Kentucky historian, was born at East Fallowfield, Pennsylvania, in 1747. He was educated at the academy of the Rev. Samuel Finley, at Nottingham, Maryland. Finley was afterwards president of Princeton University. John Filson looked askance at the Revolutionary War, and came out to Kentucky about 1783. In Lexington he conducted a school for a year, and spent his leisure hours in collecting data for a history of Kentucky. He interviewed Daniel Boone, Levi Todd, James Harrod, and many other Kentucky pioneers; and the information they gave him was united with his own observations, forming the material for his book. Filson did not remain in Kentucky much over a year for, in 1784, he went to Wilmington, Delaware, and persuaded James Adams, the town's chief printer, to issue his manuscript as The Discovery, Settlement, and Present State of Kentucke; and then he continued his journey to Philadelphia, where his map of the three original counties of Kentucky—Jefferson, Fayette, and Lincoln— was printed and dedicated to General Washington and the United States Congress. This Wilmington edition of Filson's history is far and away the most famous history of Kentucky ever published. Though it contained but 118 pages, one of the six extant copies recently fetched the fabulous sum of $1,250—the highest price ever paid for a Kentucky book. The little work was divided into two parts, the first part being devoted to the history of the country, and the second part was the first biography of Daniel Boone ever published. -

The Oedipus Myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher"

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 The ediO pus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The alF l of the House of Usher" David Glen Tungesvik Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tungesvik, David Glen, "The eO dipus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The alF l of the House of Usher"" (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16198. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16198 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Oedipus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher" by David Glen Tungesvik A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: T. D. Nostwich Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 Copyright © David Glen Tungesvik, 1996. All rights reserved. ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Masters thesis of David Glen Tungesvik has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ... .................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 "LlGEIA" UNDISCOVERED ............................................................................... 9 THE LAST OF THE USHERS .........................................................................