Poe's Paradox of Unity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Raven-Abridged.Pdf

The Raven Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately raven of the saintly days of yore. By Edgar Allen Poe Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door - Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary, Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door - Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, Perched, and sat, and nothing more. While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, `'Tis some visitor,' I muttered, `tapping at my chamber door - By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore, Only this, and nothing more.' `Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,' I said, `art sure no craven. Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the nightly shore - Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December, Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!' And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.' Eagerly I wished the morrow; - vainly I had sought to borrow From my books surcease of sorrow - sorrow for the lost Lenore - `Prophet!' said I, `thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil! For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels named Lenore - By that Heaven that bends above us - by that God we both adore - Nameless here for evermore. -

Immolation of the Self, Fall Into the Abyss in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales

Immolation of the Self, Fall into the Abyss in Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales Andreea Popescu University of Bucharest [email protected] Abstract Edgar Allan Poe’s tales offer a variety of instances linked to the analysis of human nature and the processes it goes through during the stories. Most of them treat about the destruction of the self as the narrator finds himself confronted with the darkness that gradually will come to annihilate reason and any sensible thinking. The protagonist witnesses not only the darkness inside, but also the crumbling of the world in a deliberate way of destroying all attempts at reasoning. In these tales the reader faces a transvaluation of values which leads to the description of a world without mercy and compassion. Thus, the article will explore the psychological connotations in some of the tales focussing on symbols like the mask, the fall into the abyss, the dark side of human nature. Keywords : divided self, self-immolation, space, time, transcendentalism In his essay “The Philosophy of Composition” Edgar Allan Poe states that the artist’s primary duty is not to exorcise despair, but rather to present it as the primary psychological response to reality and to render it as faithfully as possible. In a poem like “Ulalume,” the imagery alternates between hope and despair. Poe’s final resolute vision is that hope deludes and destroys. In the general picture he makes of human psychology Poe sees despair as a correct response to the hopelessness of human life, considering that hope has been driven away once and for all. -

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

“The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe 1 Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, 31 Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning, 2 Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore — 32 Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before. 3 While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, 33 "Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice; 4 As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. 34 Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore — 5 "'Tis some visiter," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door — 34 Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;— 6 Only this and nothing more." 36 'Tis the wind and nothing more!" 7 Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; 37 Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, 8 And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. 38 In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore; 9 Eagerly I wished the morrow; — vainly I had sought to borrow 39 Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; 10 From my books surcease of sorrow — sorrow for the lost Lenore — 40 But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door — 11 For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore — 41 Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door — 12 Nameless here for evermore. -

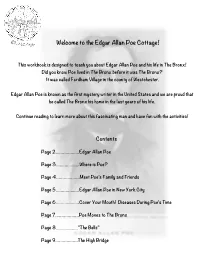

Poe Work Packet

Welcome to the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage! This workbook is designed to teach you about Edgar Allan Poe and his life in The Bronx! Did you know Poe lived in The Bronx before it was The Bronx? It was called Fordham Village in the county of Westchester. Edgar Allan Poe is known as the first mystery writer in the United States and we are proud that he called The Bronx his home in the last years of his life. Continue reading to learn more about this fascinating man and have fun with the activities! Contents Page 2……………….Edgar Allan Poe Page 3……………….Where is Poe? Page 4……………….Meet Poe’s Family and Friends Page 5……………….Edgar Allan Poe in New York City Page 6……………….Cover Your Mouth! Diseases During Poe’s Time Page 7……………….Poe Moves to The Bronx Page 8………………”The Bells” Page 9………………The High Bridge Edgar Poe was born in 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts to actors! He would travel with his mother to shows she performed in. Sadly, she died, but the Allan family took him in and raised him. This is how he took the Allan name. When he grew up he moved around a lot. He lived in Richmond, Virginia, London, England, Baltimore, Maryland, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Boston, Massachusetts, and New York City, New York writing poetry and short stories! He even studied at West Point Military Academy for a time. It was in Baltimore where he met and married his wife Virginia. Virginia and her mother, Maria Clemm, moved to New York City with Edgar. -

The Oedipus Myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher"

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 The ediO pus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The alF l of the House of Usher" David Glen Tungesvik Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tungesvik, David Glen, "The eO dipus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The alF l of the House of Usher"" (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16198. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16198 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Oedipus myth in Edgar A. Poe's "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher" by David Glen Tungesvik A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: T. D. Nostwich Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 Copyright © David Glen Tungesvik, 1996. All rights reserved. ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Masters thesis of David Glen Tungesvik has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ... .................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 "LlGEIA" UNDISCOVERED ............................................................................... 9 THE LAST OF THE USHERS ......................................................................... -

The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe 1 Once Upon a Midnight Dreary, While I Pondered, Weak and Weary, 2 Over Many a Quaint and Curi

1 The Raven By Edgar Allan Poe 2 Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, 3 Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore— 4 While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, 5 As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. 6 “’Tis some visiter,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door— 7 Only this and nothing more.” 8 9 Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; 10 And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. 11 Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow 12 From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore— 13 For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore— 14 Nameless here for evermore. 15 16 And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain 17 Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before; 18 So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating 19 “’Tis some visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door— 20 Some late visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door;— 21 This it is and nothing more.” 22 23 Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer, 24 “Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore; 25 But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, 26 And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door, 27 That I scarce was sure I heard you”—here I opened wide the door;— 28 Darkness there and nothing more. -

Edgar Allan Poe Simon & Schuster Classroom Activities for the Enriched Classic Edition of the Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe

Simon & Schuster Classroom Activities For the Enriched Classic edition of The Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe Simon & Schuster Classroom Activities For the Enriched Classic edition of The Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe Each of the three activities includes: • NCTE standards covered • An estimate of the time needed • A complete list of materials needed • Step-by-step instructions • Questions to help you evaluate the results The curriculum guide and many other curriculum guides for Enriched Classics and Folger Shakespeare Library editions are available on our website, www.simonsaysteach.com. The Enriched Classic Edition of The Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe includes: • An introduction that provides historical context and outlines the major themes of the work • Critical excerpts • Suggestions for further reading Also Available: More than fifty classic works are now available in the new Enriched Classic format. Each edition features: • A concise introduction that gives the reader important background information • A chronology of the author’s life and work • A timeline of significant events that provides the book’s historical context • An outline of key themes and plot points to help readers form their own interpretations • Detailed explanatory notes • Critical analysis, including contemporary and modern perspectives on the work • Discussion questions to promote lively classroom discussion • A list of recommended related books and films to broaden the reader’s experience Recent additions to the Enriched Classic series include: • Beowulf, Anonymous, ISBN 1416500375, $4.95 • The Odyssey, Homer, ISBN 1416500367, $5.95 • Dubliners, James Joyce, ISBN 1416500359, $4.95 • Oedipus the King, Sophocles, ISBN 1416500332, $5.50 • The Souls of Black Folks, W.E.B. -

View Fast Facts

FAST FACTS Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe “Author's Works and Themes: Edgar Allan Poe.” Gale, 2019, www.gale.com. Writings by Edgar Allan Poe • Tamerlane and Other Poems (poetry) 1827 • Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (poetry) 1829 • Poems (poetry) 1831 • The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, North America: Comprising the Details of a Mutiny, Famine, and Shipwreck, During a Voyage to the South Seas; Resulting in Various Extraordinary Adventures and Discoveries in the Eighty-fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude (novel) 1838 • Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (short stories) 1840 • The Raven, and Other Poems (poetry) 1845 • Tales by Edgar A. Poe (short stories) 1845 • Eureka: A Prose Poem (poetry) 1848 • The Literati: Some Honest Opinions about Authorial Merits and Demerits, with Occasional Words of Personality (criticism) 1850 Major Themes The most prominent features of Edgar Allan Poe's poetry are a pervasive tone of melancholy, a longing for lost love and beauty, and a preoccupation with death, particularly the deaths of beautiful women. Most of Poe's works, both poetry and prose, feature a first-person narrator, often ascribed by critics as Poe himself. Numerous scholars, both contemporary and modern, have suggested that the experiences of Poe's life provide the basis for much of his poetry, particularly the early death of his mother, a trauma that was repeated in the later deaths of two mother- surrogates to whom the poet was devoted. Poe's status as an outsider and an outcast--he was orphaned at an early age; taken in but never adopted by the Allans; raised as a gentleman but penniless after his estrangement from his foster father; removed from the university and expelled from West Point--is believed to account for the extreme loneliness, even despair, that runs through most of his poetry. -

Annabel Lee by Edgar Allan Poe

Name _______________________________________________ Date ____________________ Mod ___ Annabel Lee by Edgar Allan Poe It was many and many a year ago, In a kingdom by the sea, That a maiden there lived whom you may know By the name of Annabel Lee; And this maiden she lived with no other thought Than to love and be loved by me. I was a child and she was a child, In this kingdom by the sea; But we loved with a love that was more than love- I and my Annabel Lee; With a love that the winged seraphs of heaven Coveted her and me. And this was the reason that, long ago, In this kingdom by the sea, A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling My beautiful Annabel Lee; So that her highborn kinsman came And bore her away from me, To shut her up in a sepulchre In this kingdom by the sea. The angels, not half so happy in heaven, Went envying her and me- Yes!- that was the reason (as all men know, In this kingdom by the sea) That the wind came out of the cloud by night, Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee. But our love it was stronger by far than the love Of those who were older than we- Of many far wiser than we- And neither the angels in heaven above, Nor the demons down under the sea, Can ever dissever my soul from the soul Of the beautiful Annabel Lee. For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side Of my darling- my darling- my life and my bride, In the sepulchre there by the sea, In her tomb by the sounding sea. -

Woman Representation in Poe's to Helen

WOMAN REPRESENTATION IN POE’S TO HELEN Fiola Kuhon Bina Sarana Informatika University, PSDKU Tegal [email protected] ABSTRACT Sir. Edgar Allan Poe was recognized for his gothic yet in depth writings. Every object he put in his works ended up as an interesting center of a literary study. Therefore, the aim of this research was to analyze the representation of a woman in Poe’s To Helen, the first version of the poem published in 1831. Meanwhile, to analyze the poem, an expressive approach and feminism approach were applied during this research. Hence, this research was a descriptive research where all the data were obtained and presented in words. Having analyzed this poem, it was discovered that in this poem, Poe depicted woman opposite to his major theme of beautiful victimized women. In this poem, the woman was represented as fair, caring, comforting and full of wisdom to the extent where a person found love and home in her. Keywords: Woman, Representation, Depiction, Poe, To Helen, Poem 1. Introduction Poetry is a work where someone inspirations. Women had been the can sum up ample and deep story in a subject of numerous poems written by short manner. However, as short as it Poe, and there were considerably might seem, a poem covers more than amount of them are entitled after the what can be imagined by the readers. female character. “To Helen” (1831), Therefore, whoever or whatever the “Lenore” (1831), “Eulalie – A Song” object of the poem is, they must hold a (1845), “Ulalume – A Ballad” (1847), special place in the poet’s heart. -

AM Edgar Allan Poe Subject Bio & Timeline

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMastersPBS American Masters – Edgar Allan Poe: Buried Alive Premieres nationwide Monday, October 30 at 9/8c on PBS (check local listings) for Halloween Edgar Allan Poe Bio & Timeline In biography the truth is everything. — Edgar Allan Poe Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, January 19, 1809, the son of two actors. By the time he was three years old, his father had abandoned the family and his mother, praised for her beauty and talent, had succumbed to consumption. Her death was the first in a series of brutal losses that would resonate through Poe’s prose and poetry for the duration of his life. Poe was taken in by John Allan, a wealthy Richmond merchant and an austere Scotsman who believed in self-reliance and hard work. His wife, Francis, became a second mother to Poe – until, like Poe’s mother, she died. Allan, who had never formally adopted Poe, became increasingly harsh toward the young man and the two clashed frequently. Eventually, Poe left the Allan home, vowing to make his way in the world alone. By the time he was 20, Poe’s dreams of living as a southern gentleman were dashed. After abandoning a military career during which he published his first book of poetry, Poe landed in Baltimore and took refuge with an aunt, Maria Clemm, and her 13-year-old daughter, Virginia, whom he would later marry despite a significant age difference. -

The Representation of Women in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Elien Martens The Representation of Women in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe Masterproef voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Engels - Spaans Academiejaar 2012-2013 Promotor Prof. Dr. Gert Buelens Vakgroep Letterkunde 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. Gert Buelens, without whom this dissertation would not have been possible. His insightful remarks, useful advice and continuous guidance and support helped me in writing and completing this work. I could not have imagined a better mentor. I would also like to thank my friends, family and partner for supporting me these past months and for enduring my numerous references to Poe and his works – which I made in every possible situation. Thank you for being there and for offering much-needed breaks with talk, coffee, cake and laughter. Last but not least, I am indebted to one more person: Edgar Allan Poe. His amazing – although admittedly sometimes rather macabre – stories have fascinated me for years and have sparked my desire to investigate them more profoundly. To all of you: thank you. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. The number of women in Poe’s poems and prose ..................................................................... 7 2. The categorization of Poe’s women ................................................................................................ 9 2.1 The classification of Poe’s real women – BBC’s Edgar Allan Poe: Love, Death and Women......................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 The classification of Poe’s fictional women – Floyd Stovall’s “The Women of Poe’s Poems and Tales” ................................................................................................................................. 11 3.