Clean DRAFT Food Cartology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Double X-Small Double Small Double Medium Double Large Double X-Large COPPERS and BRASSES

COPPERS AND BRASSES Double X-Small Double Small Double Medium Double Large Double X-Large COPPERS AND BRASSES Double is an exploration in extremes. The family evolves in a linear way but on two axis at the same time. The heavier it gets, the wider it gets. Therefore, the styles in this display typeface define the way they want to be used. If you want to make sure your text always overflows, use the X-Large. If you want to make sure your text always feels like too few words, use the X-Small. The choice is yours. Double — coppersandbrasses.com 2 COPPERS AND BRASSES FAT Fruiterie Truite Espresso shot Mile End Street-Food Double — coppersandbrasses.com 3 COPPERS AND BRASSES BAGELS Is it Hot & Spicy ? Quartier Currywurst and Fries ENERGIZING MEAL Pindasaus ! Trinidad and Tobago QUICK AND EASY, MAKE IT AT HOME ! A lot of different ingredients Confectionné avec soin, directement de notre cuisine à votre porte Double — coppersandbrasses.com 4 COPPERS AND BRASSES Double X-Small Double Small Double Medium Double Large Double X-Large COPPERS AND BRASSES Uppercase ABCDEFGHIJKLM NOPQRSTUVWXYZ Lowercase abcdefghijklm nopqrstuvwxyz Default Figures 0123456789 Double X-Small 36 / 48 Double — coppersandbrasses.com 6 COPPERS AND BRASSES Troubleshooters Mysteriousness French-Canadian Environmentalist Quintuplicated Hypercriticism Autodestructing Double X-Small 72 / 82 Double — coppersandbrasses.com 7 COPPERS AND BRASSES Unresolvedness Straightjackets Tranquillization Whistle-Blowers Extinguishment Confrontational Hyperventilation Double X-Small 72 / 82 Double — coppersandbrasses.com 8 COPPERS AND BRASSES FLAMETHROWERS ENSHRINEMENT DISEMBARKMENT OBJECTIONABLY UNEXPENSIVELY OVERQUALIFIED SYNCHRONIZING Double X-Small 72 / 82 Double — coppersandbrasses.com 9 COPPERS AND BRASSES DEPOLYMERIZES LEISURELINESS HINDQUARTERS DECOMPOUNDING ACQUIESCENCES IMPERSONALISE VENERABLENESS Double X-Small 72 / 82 Double — coppersandbrasses.com 10 COPPERS AND BRASSES Street food is ready-to-eat food or drink sold by a hawker, or vendor, in a street or other public place, such as at a market or fair. -

Free Download

SISTER PUBLICATION Follow Us on WeChat Now Advertising Hotline 400 820 8428 AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2017 Chief Editor Frances Chen 陈满满 Production Manager Ivy Zhang 张怡然 Designers Aries Ji 季燕 Joan Dai 戴吉莹 Contributors Alyssa Marie Wieting, Betty Richardson, Celine Song, Dominic Ngai, Erica Martin, Frances Arnold, Kendra Perkins, Leonard Stanley, Manaz Javaid, Nate Balfanz, Theresa Kemp, Trevor Lai Operations Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路169号智造局2号楼305-306室 邮政编码:200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话:021-8023 2199 传真:021-8023 2190 Guangzhou 广告代理: 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 电话:020-8358 6125, 传真:020-8357 3859-800 Shenzhen 广告代理: 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 电话:0755-8623 3220, 传真:0755-8623 3219 Beijing 广告代理: 上海和舟广告有限公司 电话: 010-8447 7002 传真: 010-8447 6455 CEO Leo Zhou 周立浩 Sales Manager Doris Dong 董雯 BD Manager Tina Zhou 周杨 Sales & Advertising Jessica Ying Linda Chen 陈璟琳 Celia Chen 陈琳 Chris Chen 陈熠辉 Nikki Tang 唐纳 Claire Li 李文婕 Jessie Zhu 朱丽萍 Head of Communication Ned Kelly BD & Marketing George Xu 徐林峰 Leah Li 李佳颖 Peggy Zhu 朱幸 Zoey Zha 查璇 Operations Manager Penny Li 李彦洁 HR/Admin Sharon Sun 孙咏超 Distribution Zac Wang 王蓉铮 General enquiries and switchboard (021) 8023 2199 [email protected] Editorial (021) 8023 2199*5802 [email protected] Distribution (021) 8023 2199*2802 [email protected] Marketing/Subscription (021) 8023 2199*2806 [email protected] Advertising (021) 8023 2199*7802 [email protected] online.thatsmags.com shanghai.urban-family.com Advertising Hotline: 400 820 8428 城市家 出版发行:云南出版集团 云南科技出版社有限责任公司 -

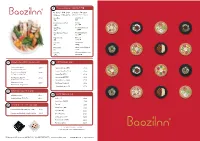

CHINATOWN1-Web

㑉ス⤇㔣╔╔㦓 Classic Hotpot Skewer Per Skewer ょ╔ £1.70 5 Skewer ╔ £7.90 13 Skewer ╔ £17.90 (Minimum Order 3 Skewer) Hot Dog Crab Stick 㦓⒎ 㨥⽄ Pork Luncheon Meat Konjac 㣙⏷㑠 ㄫ㲛ⰵ Beef Tripe Frozen Bean Curd ⊇㮠 ⛕⛛⡍ Fish Bamboo Wheel Fried Bean Curd 㻓 㱵⛛⡍ Pig’s Intestine Broccoli ➪⒎ 㣩⹊⪀ Fish Ball Cuttle Fish 㲋㠜 ㄱ㲋呷 Prawn Ball Okra (Lady’s Fingers) 㥪㠜 ㎯ⷋ Fish Tofu Chestnut Mushrooms ⛛⡍㲋 ⺃㽳ㄫ⤙ ORIENTAL MOCKTAIL 㝎㓧㯥㊹ HOT DRINKS 㑆㯥 Tender Touch ⥏䧾㨔 £3.50 Peppermint Tea ⌍⧣␒ £2.00 /\FKHHDQGDORHYHUD Lemon Grass Tea 㦓ぱ␒ £2.00 Green Vacation㓧⭯㋜ £3.50 /\FKHHDQGJUHHQWHD Lemon Tea ㆁを␒ £2.00 Jasmine Tea 䌪⺀⪀␒ £2.00 Pink Paradise ➻⨆㝢㜹 £3.50 :DWHUPHORQDQGDORHYHUD Brown Rice Tea ␄ゟ␒ £2.00 㠭㑓㎩⪋ Memories £3.50 Red Dates Tea ⨆㵌␒ £2.20 Watermelon and green tea. Grape Fruit Tea 䰔㽳␒ £2.20 MINERAL WATER ⷃ㐨㙦 SOFT DRINKS 㯥 ⷃ㐨㙦 Still Water £2.00 Sparkling Water㱸㋽ⷃ㐨㙦 £2.00 Coke £2.80 Diet Coke ☱㜽 £2.80 DESSERT OF THE DAY 㝦♇ 7up㋡㥢 £2.80 Herbal Tea 㠩⹝⭀ £2.80 ⥆䌵⡾ Homemade Herbal Grass Jelly £2.80 Soya Milk ⛛Ⰰ £2.80 Silver Ear and Lily Bulb Soup 㯢✜⊇⧩㜶 £3.00 Green Tea ␒ £2.80 Lychee Juice ⺁㺈㺏 £2.80 Aloe Vera Juice ⾵䍌㺏 £2.80 Plum Juice㚙み㜶 £2.80 Ύ&ƌĞĞtŝĮ͗ĂŽnjŝ/ŶŶ&ƌĞĞtŝĮ * Please note that dishes may not appear exactly as shown. Classic 1HZSRUW&W/RQGRQ:&+-6_7HO_ZZZEDR]LLQQFWFRP.com ⊔ᙐ㚱㱸➍㱉⍄ⳑ$OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG Noodle 奆 House Jiaozi / Wonton 儌㽳⒕㗐 Chicken & Shitake Mushroom Soup Noodles £10.50 Mixed Chengdu Dumpling with Spicy and ⛎⤙⬼㑠㜶ギ Fragrant Sauce㽻⧩㙦Ⱌ ^ĞƌǀĞĚŝŶƐĂǀŽƵƌLJďƌŽƚŚ͘ 3RUN)LOOLQJDQG3UDZQ)LOOLQJ £10.90 £9.50 Classic Chicken Noodles Mixed Wanton in Savoury Broth with ⸿㽳⬼⛃ギ Lever Seaweed 㽻⧩⒕㗐 dŽƉƉĞĚǁŝƚŚĂƌŽŵĂƟĐĐŚŝĐŬĞŶǁŝƚŚĐŚŝůůŝĞƐĂŶĚƐƉŝĐĞĚ͘ 3RUN)LOOLQJDQG3UDZQ)LOOLQJ £10.90 Zhajiang Noodles £9.50 Traditional Dumpling ⌝➝儌㽳 㷌Ⰸギ Topped with minced pork,ĨĞƌŵĞŶƚĞĚďĞĂŶƐĂƵĐĞ 3RUN)LOOLQJ £8.90 and salad. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Restaurant Oriental Wa-Lok

RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK DIRECCIÓN:JR.PARURO N.864-LIMA TÉLEFONO: (01) 4270727 RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK BOCADITOS APPETIZER 1. JA KAO S/.21.00 Shrimp dumpling 2. CHI CHON FAN CON CARNE S/.17.00 Rice noodle roll with beef 3. CHIN CHON FAN CON LAN GOSTINO S/.20.00 Rice noodle roll with shrimp 4. CHIN CHON FAN SOLO S/.14.00 Rice noodle roll 5. CHIN CHON FAN CON VERDURAS S/.17.00 Rice noodle with vegetables 6. SAM SEN KAO S/.25.00 Pork, mushrooms and green pea dumplings 7. BOLA DE CARNE S/.19.00 Steam meat in shape of ball 8. SIU MAI DE CARNE S/.18.00 Siumai dumpling with beef 9. SIU MAI DE CHANCHO Y LANGOSTINO S/.18.00 Siumai dumpling with pork and shrimp 10. COSTILLA CON TAUSI S/.17.00 Steam short ribs with black beans sauce 11. PATITA DE POLLO CON TAUSI S/.17.00 Chicken feet with black beans 12. ENROLIADO DE PRIMAVERA S/.17.00 Spring rolls 13. ENROLLADO 100 FLORES S/.40.00 100 flowers rolls 14. WANTAN FRITO S/.18.00 Fried wonton 15. SUI KAO FRITO S/.20.00 Fried suikao 16. JAKAO FRITO S/.21.00 Fried shrimp dumpling Dirección: Jr. Paruro N.864-LIMA Tel: (01) 4270727 RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK 17. MIN PAO ESPECIAL S/.13.00 Steamed special bun (baozi) 18. MIN PAO DE CHANCHO S/.11.00 Steamed pork bun (baozi) 19. MIN PAO DE POLLO S/.11.00 Steamed chicken bun (baozi) 20. MIN PAO DULCE S/.10.00 Sweet bun (baozi) 21. -

Factors Influencing Consumers' Choice of Street-Foods and Fast-Foods In

Vol. 10(4), pp. 28-39, November 2018 DOI: 10.5897/AJMM2018.0572 Article Number: F82FA1A59414 ISSN 2141-2421 Copyright © 2018 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article African Journal of Marketing Management http://www.academicjournals.org/ AJMM Full Length Research Paper Factors influencing consumers’ choice of street-foods and fast-foods in China Haimanot B. Atinkut1,2, Yan Tingwu1*, Bekele Gebisa1, Shengze Qin1, Kidane Assefa1, Biruk Yazie3, Taye Melese2, Solomon Tadesse4 and Tadie Mirie2 1College of Economics and Management, Huazhong Agricultural University, 430070 Wuhan, China. 2College of Agriculture and Rural Transformation, University of Gondar, 196, Gondar, Ethiopia. 3College of Agriculture and Environmental Science, Bahir Dar University, 79 Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. 4Department of Marketing Management, Woliso Campus, Ambo University, 19, Ambo, Ethiopia. Received 16 May, 2018; Accepted 4 October, 2018 The overarching aim of this paper is to examine empirical findings on the arena of consumers’ behavior and attitude towards intake of street-foods (SFs) and fast foods (FFs) status as well as associated risks of consumption in China. Presently, consuming SFs and FFs have become a popular trend and is counted as the manifestation of modernity in most fast growing countries, for instance, China. The SFs and FFs are believed to be a panacea to the major socio-economic problems for countries having a large population. Over one-quarter of the century FFs and SFs become rapidly expanded in China through the quick service provision of already prepared foods with reasonable prices and source of employment for swarming open country and city inhabitants end to end to its supply. -

Gaceta 1 Signos 20200203

S-SNP/SERV/P/301/R03 BOLETIN DE PUBLICACIONES SIGNOS DISTINTIVOS CORRESPONDIENTE A DICIEMBRE 2019 LA PAZ - BOLIVIA SECCIÓN 1 SOLICITADAS DENOMINATIVAS DECISIÓN 486 de la Comunidad Andina Régimen Común sobre Propiedad Industrial CAPÍTULO II Del Procedimiento de Registro Artículo 146.- Dentro del plazo de treinta días siguientes a la fecha de la publicación, quien tenga legítimo interés, podrá presentar, por una sola vez, oposición fundamentada que pueda desvirtuar el registro de la marca. A solicitud de parte, la oficina nacional competente otorgará, por una sola vez un plazo adicional de treinta días para presentar las pruebas que sustenten la oposición. Las oposiciones temerarias podrán ser sancionadas si así lo disponen las normas nacionales. No procederán oposiciones contra la solicitud presentada, dentro de los seis meses posteriores al vencimiento del plazo de gracia a que se refiere el artículo 153, si tales oposiciones se basan en marcas que hubiesen coexistido con la solicitada. NÚMERO DE PUBLICACIÓN 214055 NOMBRE DEL SIGNO RAPIDLASH GENERO DEL SIGNO Marca Producto TIPO DE SIGNO Denominación NÚMERO DE SOLICITUD 3006 - 2019 FECHA DE SOLICITUD 09/07/2019 NOMBRE DEL TITULAR Lifetech Resources LLC. DIRECCIÓN DEL TITULAR 700 Science Drive Moorpark, California 93021, Estados Unidos de América PAÍS DEL TITULAR US Estados Unidos de América NOMBRE DEL APODERADO Julio Quintanilla Quiroga DIRECCIÓN DEL APODERADO Av. José Salmón Ballivián (Los Álamos) No. 322, la Florida, La Paz – Bolivia CLASE INTERNACIONAL 3 PRODUCTOS Preparaciones cosméticas, principalmente, pestañina y acondicionador para tratamiento de las pestañas NÚMERO DE PUBLICACIÓN 214056 NOMBRE DEL SIGNO PURMO GENERO DEL SIGNO Marca Producto TIPO DE SIGNO Denominación NÚMERO DE SOLICITUD 4698 - 2019 FECHA DE SOLICITUD 15/10/2019 NOMBRE DEL TITULAR Purmo Group Oy Ab DIRECCIÓN DEL TITULAR Bulevardi 46 00120 Helsinki Finland PAÍS DEL TITULAR FI Finlandia NOMBRE DEL APODERADO Perla Koziner U. -

Peraturan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat Dan Makanan Republik Indonesia Nomor 1 Tahun 2015 Tentang Kategori Pangan

BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA PERATURAN KEPALA BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 1 TAHUN 2015 TENTANG KATEGORI PANGAN DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA KEPALA BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA, Menimbang : a. bahwa kategori pangan merupakan suatu pedoman yang diperlukan dalam penetapan standar, penilaian, inspeksi, dan sertifikasi dalam pengawasan keamanan pangan; b. bahwa penetapan kategori pangan sebagaimana telah diatur dalam Keputusan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan Nomor HK.00.05.42.4040 Tahun 2006 perlu disesuaikan dengan perkembangan ilmu pengetahuan dan teknologi serta inovasi di bidang produksi pangan; c. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a dan huruf b perlu menetapkan Peraturan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan tentang Kategori Pangan; Mengingat : 1. Undang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1999 tentang Perlindungan Konsumen (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1999 Nomor 42, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3281); 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 36 Tahun 2009 tentang Kesehatan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2009 Nomor 144, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5063); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 18 Tahun 2012 tentang Pangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2012 Nomor 227, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5360); 4. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 69 Tahun 1999 tentang Label dan Iklan pangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1999 Nomor 131, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3867); BADAN PENGAWAS OBAT DAN MAKANAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA - 2 - 5. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 28 Tahun 2004 tentang Keamanan, Mutu, dan Gizi Pangan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2004 Nomor 107, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4244); 6. Keputusan Presiden Nomor 103 Tahun 2001 tentang Kedudukan, Tugas, Fungsi, Kewenangan, Susunan Organisasi, dan Tata Kerja Lembaga Pemerintah Non Departemen sebagaimana telah beberapa kali diubah terakhir dengan Peraturan Presiden Nomor 3 Tahun 2013; 7. -

Food in China.Pdf

Food in China Each region of China has its own type of food. Chuan food is hot and spicy; Beijing cooking is done with a lot of meat and vegetables (including the most famous Chinese dish of all, Peking Duck); Cantonese traditions include dim sum and delicacies like shark's fin soup; Shanghai cuisine is prepared with plenty of seafood and oil. Drinks Soft drinks abound in China, both foreign brands and local. You can also buy bottled water everywhere. Other than tea, soft drinks, or bottled water, beer is your best bet. Chinese beer is generally quite good, Qingdao being the best-known brand, and almost every town has its own brew which varies from watery-but-incredibly-cheap to not-bad-and-incredibly- cheap. Beware of Chinese "wine" which is actually powerful grain alcohol. Popular Dishes Jiaozi. Dumplings. These are popular all over China, and come fried, steamed or boiled, and are stuffed with just about everything. Traditionally, families make and eat jiaozi for the Chinese New Year or Spring Festival. Making jiaozi is a social event with a group of people stuffing the dumplings together, the idea being that many hands make light work, and the result is all the tastier for your having participated in the preparation! You can order a plate of jiaozi in a restaurant, or you'll find them served in little snack food joints, often in soup (jiaozi tang). Baozi Steamed buns stuffed with a variety of fillings. These are great snacks that you'll find all over China in various different sizes and varieties. -

Qualifi Level 3 Diploma in Chinese Culinary Arts

Qualifi Level 3 Diploma in Chinese Culinary Arts Specification (For Centres) July 2019 All course materials, including lecture notes and other additional materials related to your course and provided to you, whether electronically or in hard copy, as part of your study, are the property of (or licensed to) QUALIFI Ltd and MUST not Be distriButed, sold, puBlished, made availaBle to others or copied other than for your personal study use unless you have gained written permission to do so from QUALIFI Ltd. This applies to the materials in their entirety and to any part of the materials. Qualifi Level 3 Diploma in Chinese Culinary Arts Specification May 2021 About QUALIFI QUALIFI provides academic and vocational qualifications that are globally recognised. QUALIFI’s commitment to the creation and awarding of respected qualifications has a rigorous focus on high standards and consistency, beginning with recognition as an Awarding Organisation (AO) in the UK. QUALIFI is approved and regulated by Ofqual (in full). Our Ofqual reference number is RN5160. Ofqual is responsible for maintaining standards and confidence in a wide range of vocational qualifications. As an Ofqual recognised Awarding Organisation, QUALIFI has a duty of care to implement quality assurance processes. This is to ensure that centres approved for the delivery and assessment of QUALIFI’s qualifications and awards meet the required standards. This also safeguards the outcome of assessments and meets national regulatory requirements. QUALIFI’s qualifications are developed to be accessible to all learners in that they are available to anyone who is capable of attaining the required standard. QUALIFI promotes equality and diversity across aspects of the qualification process and centres are required to implement the same standards of equal opportunities and ensure learners are free from any barriers that may restrict access and progression. -

A Food Blog Production

SpicyTones - A food blog production Eva Pennanen Thesis Degree programme in Hotel, Restaurant and Tourism Management January 2014 Abstract 24.02.2014 Degree programme in Hotel, Restaurant and Tourism Management Author or authors Group or year of Eva Pennanen entry 2010 Title of report Number of SpicyTones - A food blog production pages and appendices 61+18 Teacher(s) or supervisor(s) Johanna Rajakangas- Tolsa, Birgitta Nelimarkka This thesis is written to demonstrate the learning outcome of the author in creating a food blog project, named SpicyTones. The goals of the thesis are to create a successful food blog, to educate the society about Asian food and encourage them to cook at home. The objectives of the thesis are to obtain at least 50 followers, to keep the blog running for at least 3 months and to share out 12 themed recipes onto the blog. In this thesis, figures and tables are used in order to support the findings of the author. The thesis consists of theoritical background related to blog, blogging and its history, whereas information about Malaysian food and cultures is also studied due to the fact that the author is sharing mainly Malaysian recipes onto her blog. The author explains how the Malaysian food and cultures evolved through centuries that tranforms Malaysia as a cultural melting pot. In order to find out what are the key elements of a successful blog, the author also completed a study about awarded food blogs based on both International and Finnish scopes. A few key points are analysed and compared between bloggers. -

Grandma and Grandpa Chin's Home Recipes Hilda Hoy Rediscovers the Flavors of Her Taiwanese Childhood the CLEAVER QUARTERLY 75

Grandma and Grandpa Chin's Home Recipes Hilda Hoy rediscovers the flavors of her Taiwanese childhood THE CLEAVER QUARTERLY 75 decluttering unearthed my grandmother’s long-buried recipe booklet, I was up for the challenge. A Chinese dictionary app helped me decipher all 14 recipes. There were a handful hen I opened my mailbox to of simple snacks, like glazed roasted peanuts find an envelope from my (kao huasheng mi 烤花生米), preserved yellow mother, I knew instantly soy beans (sun dou 筍豆), or that ubiquitous what was inside. I had been W old favorite, tea eggs (chaye dan 茶葉蛋). Also, missing the food I grew up on in Taiwan, bangbang ji (棒棒雞 , a cold Sichuan appetizer and so when my mother mentioned she’d ) of shredded chicken with cucumber and a produced a collection of family recipes as spicy sesame dressing. Flipping the pages, I party favors for my grandparents’ 60th found a recipe for cai baozi (菜包子), steamed anniversary banquet, I insisted she send me buns with a vegetable filling, and the greedy a copy. Having just moved halfway around kid in me perked up. “Make those. And soon,” the world to Berlin, where I knew nobody she insisted. I vividly remember snacking on and didn’t speak the language, I couldn’t be baozi as a child on the streets of Taipei. The at that banquet. My hopes grew as I waited vendor would dole out them out in flimsy for the cookbook to arrive, and I pictured plastic bags, and I would ignore my scalded the splendid Chinese feast I would soon be fingertips to take greedy bites, the yeasty- making.