Climmers and Collectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline Chapter 1 Everyone my age remembers where they were and what they were doing when they first heard about the contest. I was sitting in my hideout watching cartoons when the news bulletin broke in on my video feed, announcing that James Halliday had died during the night. I’d heard of Halliday, of course. Everyone had. He was the videogame designer responsible for creating the OASIS, a massively multiplayer online game that had gradually evolved into the globally networked virtual reality most of humanity now used on a daily basis. The unprecedented success of the OASIS had made Halliday one of the wealthiest people in the world. At first, I couldn’t understand why the media was making such a big deal of the billionaire’s death. After all, the people of Planet Earth had other concerns. The ongoing energy crisis. Catastrophic climate change. Widespread famine, poverty, and disease. Half a dozen wars. You know: “dogs and cats living together … mass hysteria!” Normally, the newsfeeds didn’t interrupt everyone’s interactive sitcoms and soap operas unless something really major had happened. Like the outbreak of some new killer virus, or another major city vanishing in a mushroom cloud. Big stuff like that. As famous as he was, Halliday’s death should have warranted only a brief segment on the evening news, so the unwashed masses could shake their heads in envy when the newscasters announced the obscenely large amount of money that would be doled out to the rich man’s heirs. 2 But that was the rub. -

Reproduction in Mesozoic Birds and Evolution of the Modern Avian Reproductive Mode Author(S): David J

Reproduction in Mesozoic birds and evolution of the modern avian reproductive mode Author(s): David J. Varricchio and Frankie D. Jackson Source: The Auk, 133(4):654-684. Published By: American Ornithological Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1642/AUK-15-216.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1642/AUK-15-216.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Volume 133, 2016, pp. 654–684 DOI: 10.1642/AUK-15-216.1 REVIEW Reproduction in Mesozoic birds and evolution of the modern avian reproductive mode David J. Varricchio and Frankie D. Jackson Earth Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA [email protected], [email protected] Submitted November 16, 2015; Accepted June 2, 2016; Published August 10, 2016 ABSTRACT The reproductive biology of living birds differs dramatically from that of other extant vertebrates. -

The Formal Social World of British Egg-Collecting

n Cole, Edward (2016) Handle with care: historical geographies and difficult cultural legacies of egg-collecting. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7800/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Handle With Care: Historical Geographies and Difficult Cultural Legacies of Egg-Collecting Edward Cole Submitted for the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School of Geographical and Earth Sciences College of Science and Engineering University of Glasgow Abstract This thesis offers an examination of egg-collecting, which was a very popular pastime in Britain from the Victorian era well into the twentieth century. Collectors, both young and old, would often spend whole days and sometimes longer trips in a wide variety of different habitats, from sea shores to moorlands, wetlands to craggy mountainsides, searching for birds’ nests and the bounty to be found within them. Once collectors had found and taken eggs, they emptied out the contents; hence, they were really egg shell collectors. Some egg collectors claimed that egg-collecting was not just a hobby but a science, going by the name of oology, and seeking to establish oology as a recognised sub- discipline of ornithology, these collectors or oologists established formal institutions such as associations and societies, attended meetings where they exhibited unusual finds, and also contributed to specialist publications dedicated to oology. -

The Oologists Record. Edited. by Kenneth L. Skinner. All Rights

HE L I ’ T OO OG STS REC ORD. Ed i te d b K EN NET H L I y . S K N NER . A LL HT S R E ER V RIG S ED . — Vol No . M ar h 1 1 923 . III [ c , OB S ERV AT I ONS ON T HE NEST ING OF T HE DOTT EREL ( Charadri us By NOR MA N GI LROY . In the course c f a short visit to the Grampians in the spring — — of the year 1 922 I had a somewhat interesting experience P of this charming and attractive lover in its nesting haunts , some l v 3000 feet above sea leve . I arri ed at my centre on the evening — of June lst a perfect summer day it had been throughout my u . i jo rney , hot and cloudless Within an hour of my arr val in - Inverness shire , however , the wind stole round to the north without ll m . warning an icy arctic mist crept along the va ey , and at p — — summer time a thick white blanket lay on the hills almost down to the road and to the Highland Line lying at their base . ‘ The l and morning broke dul cheerless , and , except that it was T e . h dry , without a single redeeming feature prospect of climbing to the high tops was , to say the least of it , uninviting , and we reluctantly determined that there was nothing for i t bu t to spend - the day along the river on the lower ground . -

Forgotten Science of Bird Eggs: the Life Cycle of Oology at the Smithsonian Institution Katherine Nicole Crosby University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Forgotten Science of Bird Eggs: The Life Cycle of Oology at the Smithsonian Institution Katherine Nicole Crosby University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Crosby, K. N.(2015). Forgotten Science of Bird Eggs: The Life Cycle of Oology at the Smithsonian Institution. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3283 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORGOTTEN SCIENCE OF BIRD EGGS: THE LIFE CYCLE OF OOLOGY AT THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION by Katherine Nicole Crosby Bachelor of Arts University of Michigan, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Allison Marsh, Director of Thesis Ann Johnson, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Katherine Nicole Crosby, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my family. Thank you to my parents, Kristy, Mike, Gary, and Cheryl, for providing encouragement and humor when I needed it most. To my siblings, Cody, Alexi, Zoe, and Tobin, thank you for always making me laugh and keeping me honest. To my grandparents, Max, Phyllis, Gary, Jane, Sue, Mike, Roger, Nancy, and Charlotte, thank you for the many adventures and for helping me grow. -

Oology Unshelled John M

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS Some birds evolve signature egg colours and patterns to confuse nest parasites such as the cuckoo finch. Each column shows eggs from one host species. ORNITHOLOGY Oology unshelled John M. Marzluff extols a rich history of ornithology’s debt to egg collecting. im Birkhead has spent much of the fascinate Birkhead own eggs. This, however, is only part of the past four decades watching birds, and even as he laments this story of egg colour. Other species’ eggs are in particular mucking around guano- now illegal and inad- marked to camouflage them: the Japanese Tcovered ledges on which seabirds breed. His missible practice. He quail (Coturnix japonica), for example, lays insights have revolutionized ornithologists’ tracked down many heavily mottled eggs in nest sites with match- understanding of mate fidelity; his ability to old collections to learn ing patterns. Some eggs, such as that of the distil complex science for the general reader, more about the evolu- ostrich (Struthio camelus), are white to pro- for example in Bird Sense (Bloomsbury, tion of shape and col- tect the developing chick from the heat of the 2013), has revealed what it is like to be a bird. our. Through careful Sun. Others are brightly coloured, as with the Now, with an eye on past discoveries and per- evaluation of alterna- The Most Perfect American robin (Turdus migratorius), whose sistent puzzles, The Most Perfect Thing reveals tive hypotheses, he Thing: Inside (and blue eggs advertise the quality of the brood- AND CLAIRE SPOTTISWOODE ELEANOR CAVES what it is like to become a bird — from nas- dispels the common Outside) a Bird’s ing female. -

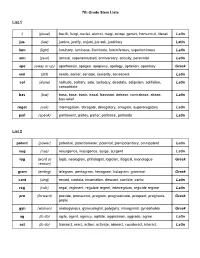

7Th Grade Stem Lists List 1 I (Plural) Bacilli, Fungi, Nuclei, Alumni, Magi

7th Grade Stem Lists List 1 i (plural) bacilli, fungi, nuclei, alumni, magi, octopi, gemini, homunculi, literati Latin jus (law) justice, justify, unjust, jus soli, justiciary Latin lum (light) luminary, luminous, illuminate, luminiferous, superluminous Latin ann (year) annual, superannuated, anniversary, annuity, perennial Latin apo (away or up) apotheosis, apogee, apoplexy, apology, aphelion, apostasy Greek sen (old) senile, senior, senator, seniority, senescent Latin sol (alone) solitude, solitary, solo, soliloquy, desolate, solipsism, solifidian, Latin consolidate bas (low) bass, base, basic, basal, bassoon, debase, contrabase, abase, Latin basrelief rogat (ask) interrogation, abrogate, derogatory, arrogate, supererogatory Latin parl (speak) parliament, parley, parlor, parlance, parlando Latin List 2 potent (power) potential, potentiometer, potentat, plenipotentiary, omnipotent Latin sug (rise) resurgence, insurgence, surge, surgent Latin log (word or logic, neologism, philologist, logician, illogical, monologue Greek reason) gram (writing) telegram, pentagram, hexagram, hologram, grammar Greek cant (sing) recant, cantata, incantation, descant, canticle, canto Latin reg (rule) regal, regiment, regulate regent, interregnum, regicide regime Latin pro (forward) provide, pronounce, program, prognosticate, prospect, prognosis, Greek prolix gyn (woman) androgynous, gynecologist, polygyny, misogynist, gynephobia Greek ag (to do) agile, agent, agency, agitate, aggression, aggrade, agree Latin act (to do) transact, react, action, activate, -

Science K Through 6

Building fun and creativity into standards-based learning Science K through 6 Ron De Long, M.Ed. Janet B. McCracken, M.Ed. Elizabeth Willett, M.Ed. © 2007 Crayola, LLC Easton, PA 18044-0431 Acknowledgements This guide and the entire Crayola® Dream-Makers® series would not be possible without the expertise and tireless efforts of Ron De Long, Jan McCracken, and Elizabeth Willett. Your passion for children, the arts, and creativity are inspiring. Thank you. Special thanks also to Dawn Dubbs for her content-area expertise, writing, research, and cur- riculum development of this guide. Crayola also gratefully acknowledges the teachers and students who tested the lessons in this guide: Barbi Bailey-Smith, Little River Elementary School, Durham, NC Susan Bivona, Mount Prospect Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ Jennifer Braun, Mount Prospect Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ Ralph Caouette, Wachusett Regional School, Holden, MA Billie Capps, Little River Elementary School, Durham, NC Judy Collier, Little River Elementary School, Durham, NC Judy Curtis, Madison Elementary School, Colorado Springs, CO Regina DeFrancisco, Liberty Corner Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ Linda Devlin, Lacey Middle School, Forked River, NJ Kathy Gerdts-Senger, Clearview Elementary School, Clear Lake, MN Mignon Hatton, Landmark Elementary School, Little Rock, AR Craig Hinshaw, Hiller Elementary School, Madison Heights, MI Nancy Knutsen, Triangle Elementary School, Hillsborough, NJ Kimberlyn Koirtyohann, Fort Worth Academy, Fort Worth, TX Linda Kondikoff, Asa -

Blue Jay, Vol.40, Issue 3

OOLOGY ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS: AN HISTORICAL PREVIEW C. STUART HOUSTON, 863 University Drive, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 0J8 and MARC J. BECHARD, Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia. 25701 As part of a study of native raptor in The Zoologist and The Ibis between populations on the North American 1859 and 1863.10 An active collector of prairie, we have surveyed oologic bird specimens, Blakiston also sent a records for information on early bird few eggs taken in 1858 to the Smith¬ distribution patterns. The senior author sonian Institution in Washington, D.C. surveyed all issues of The Oologist from These were: 2 sets (6 eggs each) of 1886 to 1894 and The Nidiologist (later Brewer’s Blackbird on 3 June, 1 set of spelled The Nidologist) from 1893 to Goshawk (4 eggs) on 7 May, 1 set of 1896 and found interesting material on Merlin (4 eggs) on 25 May, and 1 set the nesting of prairie birds. Fewer useful each of American Coot, Sharp-tailed items were located in The Young Grouse, and Mallard without specific Oologist (1884-1885), Ornithologist and dates. Only 1 egg of each of these sets Oologist (1881-1893), The Hawkeye is extant. Bendire, in Volume 1 of his Ornithologist and Oologist (1888-1918), Life Histories of North American Birds The Avifauna (1895-1897), The Ottawa published by the Smithsonian in 1892, Naturalist (1887-1918), and The Journal of Comparative Oology (1920-1922). The junior author studied raptor sets in Canadian and American museums, particularly the collection of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology (WFVZ) in Los Angeles. -

On the Oology of the North American Pygopodes (With Five Photos by The

July, 1914 PECULIAR DEATH OF CALIFORNIA BUSH-TIT 169 This beautiful and, to the writer, unusual covering of the nest was quite sufficient to invite still closer examination, and the most unusual feature was yet to be discovered. On drawing down the supporting branchesto facilitate closer inspection, I was surprised to observe the tail and wing-tips of a bush- tit projecting from the side of the nest a couple of inches to the left of the entrance. Upon investigation I found that one of the little nest builders, for some reason which seems difficult to explain, had apparently attempted to tunnel through the side of the nest and, becoming entangled in the netlike structure to such extent that it could not free itself, had perished. The bird was thoroughly dried when found, so the nest was brought in and photo- graphed (see fig. 49). The tail and wings of the dead bird will be seen pro- jecting from the nest a little to the left of the entrance. The nest contained five eggs, three of which were broken. They had ap- parently been deposited at least two weeks previously, which would indicate a rather early nesting date for the species. Los Angeles, Califonzia, May 6, 1914. ON THE OOLOGY OF THE NORTH AMERICAN PYGOPODES . By DR. R. W. SHUFELDT WITH FIVE PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR AKEN collectively, the loons and grebes form a natural Supersuborder of birds, created to contain the Suborder Pygopodes, which latter is T represented by two families, namely the Colymbidae or Grebes, and the Gaviidae or Loons. -

Species Library Profiles 12 December 2013 Final

EPA/600/R-14/009 Avian Life-History Profiles for Use in the Markov Chain Nest Productivity Model (MCnest) Version: 12 December 2013 Richard S. Bennett and Matthew A. Etterson Mid-Continent Ecology Division National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development U. S. Environmental Protection Agency Duluth, MN 55804 Species Life-History Profiles – 12 December 2013 Blank Page 2 Species Life-History Profiles – 12 December 2013 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................5 Approach ..........................................................................................................................................5 Required parameters ................................................................................................................... 7 a. Initiation probability .......................................................................................................... 8 b. Daily background nest failure rate during laying and incubation (m 1) ............................ 8 c. Daily background nest failure rate during nestling rearing (m 2) ...................................... 9 d. Date of first egg laid in first nest of season (T 1) ................................................................ 9 e. Date of first egg laid in last nest of season (T last ) .............................................................. 9 f. Length of rapid follicle growth period -

Commentaries and Reviews

COMMENTARIES AND REVIEWS Editorial Comment . - This section has been established as a forum for the exchange of ideas, opinions, position statements, policy recommendations, and other reviews regarding turtle-related matters. Commentaries and points of view represent the personal opinions of the authors, and are peer-reviewed only to the extent necessary to help authors avoid clear errors or obvious misrepresentations or to improve the clarity of their submission, while allowing them the freedom to express opinions or conclusions that may be at significant variance with those of other authorities . We hope that controversial opinions expressed in this section will be counterbalanced by responsible replies from other specialists, and we encourage a productive dialogue in print between the interested parties . Shorter position statements , policy recommendations , book reviews, obituaries, and other reports are reviewed only by the editorial staff. The editors reserve the right to reject any submissions that do not meet clear standards of scientific professionalism . Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 1998, 3(1):118-123 © 1998 by Chelonian Research Foundation many chelonian studies (listed by Hinton et al., 1997), including those of threatened species for which it was How to Minimize Risk and originally developed. For examp le, from 1979 until 1986, all Optimize Information Gain in Assessing known females of P. umbrina were annually radiographed Reproducti ve Conditio n and Fecundit y during the breeding season (Burbidge, 1983). However, by 1986 the population of P. umbrina had declined to less than of Live Female Chelonians 50 individuals. In view of the potential risk to the last survivors of this species, I recommended cessation of radi G ERALD K UCHLING 1 ography when I arrived in Western Australia in 1987, and instead introduced, for P.