Post-16 Partnerships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ysgol Calon Cymru PDF 816 KB

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL CABINET EXECUTIVE 22nd June 2021 REPORT AUTHOR: County Councillor Phyl Davies Portfolio Holder for Education and Property REPORT TITLE: Ysgol Calon Cymru REPORT FOR: Decision 1. Purpose 1.1 On the 29th September 2020, the Council’s Cabinet considered a Strategic Outline Case (SOC) which considered a range of options in order to address issues with the current operating model of Ysgol Calon Cymru, a dual stream secondary school which operates across two campuses in Mid Powys. 1.2 This is the first phase of the Ysgol Calon Cymru catchment transformation programme. The second phase will focus on reviewing primary and early years provision in the area. 1.3 Without requiring Cabinet to make a decision on the future operating model for Ysgol Calon Cymru, the SOC considered by Cabinet identified a ‘preferred way forward’, which is as follows: A new 11-18 English-medium campus in Llandrindod Wells; plus A new/remodelled 4-18 Welsh-medium all-through campus in Builth Wells. 1.4 This report requests Cabinet approval to commence informal engagement with stakeholders on the preferred way forward. 2. Background Strategy for Transforming Education in Powys 2.1 On the 14th April 2020, a new Strategy for Transforming Education in Powys was approved by the Leader via a delegated decision. 2.2 The Strategy was developed following extensive engagement with a range of stakeholders during two separate periods between October 2019 and March 2020. 2.3 The Strategy sets out a new vision for education in Powys, which is as follows: ‘All children and young people in Powys will experience a high quality, inspiring education to help develop the knowledge, skills and attributes that will enable them to become healthy, personally fulfilled, economically productive, socially responsible and globally engaged citizens of 21st century Wales.’ 2.3 The Strategy also sets out a number of guiding principles which will underpin the transformation of education in Powys. -

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to September

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-December 2020 Primary schools All Saints R.C. Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Blaen-Y-Cwm C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Coed -y- Garn Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Deighton Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Sofrydd C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Illtyd's Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Mary's Roman Catholic - Brynmawr Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Willowtown Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ysgol Bro Helyg Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ystruth Primary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Afon-Y-Felin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Archdeacon John Lewis Bridgend County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Brackla Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryncethin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryntirion Infants School Bridgend County Borough Council Cefn Glas Infant School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Cwmfelin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend -

The Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers

The Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers Flintshire and Wrexham The Flintshire and Wrexham Hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Alun School Castell Alun High School Connah’s Quay High School Flint High School Hawarden High School Holywell High School John Summers High School Saint David’s High School Saint Richard Gwyn Catholic High School Ysgol Maes Garmon The Maelor School Ysgol Rhiwabon Ysgol Morgan Llwyd Coleg Cambria For further information on the Flintshire and Wrexham hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Debra Hughes: [email protected] 27/05/2020 1 Swansea The Swansea Hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Bishop Gore School Bishop Vaughan Catholic School Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Bryn Tawe Ysgol Gyfun Gwyr Gowerton School Morriston Comprehensive School Olchfa School Gower College Swansea For further information on the Swansea hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Fiona Beresford: [email protected] Rhondda Cynon Taf and Merthyr Tydfil The Rhondda Cynon Taf and Merthyr Tydfil Hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Aberdare Comprehensive School Afon Taff High School Bishop Hedley High School Bryn Celynnog Comprehensive School Cardinal Newman High School Coleg y Cymoedd Cyfarthfa High School The College Merthyr Tydfil Ferndale Comprehensive Community School Hawthorn High School Mountain Ash Comprehensive School 27/05/2020 2 Pen-y-dre -

“I Just Want to Speak to Someone Who Understands How I Feel”

“I just want to speak to someone who understands how I feel” We are here for you 01597 824411 www.mnpmind.org.uk Registered Charity Number: 1167840 Our Mission is to improve the mental wellbeing for people in Mid and North Powys Index: Information on Mid Powys Mind Page 3 Activities in Llandrindod Wells Page 4 Wellbeing Centre Page 5 Silvercloud (North and Mid Powys) Page 6 Blended on-line CBT Service Page 6 Information on Training Page 6 Counselling Service Page 7 Walk and Talk service Page 7 Recovery Support Service Page 8 North Powys Support Page 8 Side by Side Cymru (North and Mid Powys) Page 9 Mums Matter (North and Mid Powys) Page 9 16 - 25’s group Page 10 C–Card service Page 10 High School Drop Ins Page 11 Weekly Drop in Groups Page 11 2 Office Opening Hours 9.30 a.m.- 4.00 p.m Monday to Friday Crescent Chambers South Crescent Llandrindod Wells LD1 5DH 01597 824411 Website: www.mnpmind.org.uk Email: @mnpmind.org.uk Facebook: facebook.com/mnpowysmind Twitter: @mnpowysmind Instagram: @mnpowysmind We provide support and advice throughout Mid and North Powys. You do not need a referral to speak to us. If you have any questions, or would like more information on any of our services - please ring the office and we will be happy to help. We aim to support people so they can get to a place where they feel they have recovered. “To help, respect, value, listen to and reassure me so I can learn and get better” 3 Llandrindod Activities Art group: Thursdays 10:30 - 12:30pm. -

New Mid-Powys Secondary School

Opsiynau ôl-16 Sixth Form Options 2019-21 Lefelau: Llwybrau Dysgu Levels: Learning Pathways Masters Degrees , Postgraduate Certificates, Postgraduate Diplomas HIGHER Bachelor Degrees BA/BSc., Graduate Certificates, Graduate Diplomas HONOURS Foundation Degrees, BTEC HND, NVQ Level5, Professional Development Diplomas INTERMEDIATE Certificate of Higher Education, NVQ Level 4, Certificate of Early Years Practice CERTIFICATE NVQ Level 3 National, Diploma, Extended Diploma, Access Courses, CACHE Diploma, Advanced Modern Apprenticeships, GCE A Levels (AS & A2) ADVANCED NVQ Level 2, Diploma, GNVQ Intermediate, CACHE Certificates, Access Courses, GCSE (Grades A*-C) GCSE (A*-C) NVQ Level1, Certificates and Awards, Foundation NVQ, GNVQ Foundation, GCSE (Grades D-G) FOUNDATION Students needing support to progress with their learning PRE- FOUNDATION Amserlen tebygol Typical timetable 2 week timetable (50 lessons x 60 minutes) YEAR 12 YEAR 13 A’level AREA OF STUDY Lessons/fortnight Lessons/fortnight equivalents Typical programme of 4 AS Levels (8 32 24 4/3 hours per subject) lessons lessons Welsh Baccalaureate 3 3 1 lessons lessons Personal & Social Education 1 1 0 lesson lesson Personal Study (in-school) 13 21 lessons lessons Cwricwlwm Ôl 16 De Powys South Powys Local Curriculum Secondary Schools in Powys, Neath Port Talbot College (NPTC) and Coleg Sir Gâr work together: o New Mid-Powys Secondary School o Gwernyfed High School o Brecon High School o Crickhowell High School o Maesydderwen High School o Neath and Port Talbot College o Coleg Sir Gâr -

Ysgol Calon Cymru Strategic Outline Case PDF 531 KB

CYNGOR SIR POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL. CABINET EXECUTIVE 29th September 2020 REPORT AUTHOR: County Councillor Phyl Davies Portfolio Holder for Education and Property REPORT TITLE: Ysgol Calon Cymru Strategic Outline Case (SOC) REPORT FOR: Decision 1. Purpose 1.1 This report requests Cabinet approval for the following: a) To submit a Strategic Outline Case (SOC) to the Welsh Government’s 21st Century Schools Programme for investment to develop: New facilities for 925 pupils aged 11 – 18 in Llandrindod Wells, replacing the existing poor accommodation at the current Llandrindod campus – to be built on the current Llandrindod Campus; New or remodelled facilities at Builth Wells to accommodate 450 pupils aged 4-18 along with early years facilities – to be built on the current Builth Wells Campus; Community facilities will be included but these have not yet been defined; It is the intention that the Llandrindod Wells campus would deliver English-medium provision and that the Builth Wells campus would deliver Welsh-medium provision. b) To bring back a further report to Cabinet by November 2020 outlining the school reorganisation proposals required to achieve the changes outlined above. Full consultation will be undertaken before any final decisions are made. 1.2 The cost of the preferred way forward is estimated to be £61.0 million including *8% Risk and 24% Optimism Bias, which is acceptable at SOC stage, and will be mitigated as the business case process continues into the next stages. This exceeds the funding currently available within the Council’s Band B Programme. The funding to support this project will be considered as part of the overarching financial strategy for the delivery of the entire Council’s Strategy for Transforming Education in Powys 2020-30 and a request to expand the Band B funding envelope will be made to Welsh Government. -

Powys Press Release

Powys County Council issued the following Press Release today (22 September 2020). Ambitious education plans to be considered Ambitious plans to transform education in Powys, providing learners with the world-class facilities they deserve, will be considered by Cabinet next week, the county council has confirmed. Following extensive engagement with key stakeholders including headteachers, school staff, governors, parents and learners last winter, Powys County Council is committed to bringing forward plans to deliver an improved learner offer for children and young people by delivering its Strategy for Transforming Education in Powys, which was approved in April. The four strategic aims of the strategy are – To improve learner entitlement and experience; To improve learner entitlement and experience for post-16 learners; To improve access to Welsh-medium provision across all key stages; and To improve provision for learners with special education needs / additional learning needs. To deliver these aims will require significant investment in the education infrastructure in Powys. On Tuesday, September 29, Cabinet will consider five reports which could see a potential investment of over £170m, resulting in brand new school facilities across the county as well as a proposal to consult on establishing a new all-age school. However, several small schools could close as part of the transforming education work. Cabinet will be considering the following plans: A new all-age community campus for Ysgol Bro Hyddgen Investment into Ysgol Calon Cymru for a new English-medium campus for pupils aged 11-18 in Llandrindod Well and a new/remodelled all-age Welsh medium campus in Builth Wells A major reorganisation of schools in the Llanfyllin catchment which could see the construction of a new all-age community campus for Ysgol Llanfyllin, a new area primary school to replace Llandysilio and Carreghofa primary schools which could also include schools from the Welshpool catchment area. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

September 2020

REPORT FROM COUNTY COUNCILLOR HEULWEN D HULME FOR RHIWCYNON WARD AND PORTFOLIO HOLDER FOR ENVIRONMENT, HIGHWAYS TRANSPORT & RECYCLING. SEPTEMBER 2020 CABINET 1.9.20 Annual report on Adults Social Services incorporating Residential Care, Care Staff, impact of Covid 19, Trace and Trace. Re-opening schools has been well supported by Welsh Government and included school transport, shielding for staff and children and face coverings. BUDGET WORKSHOP 1.9.20 Due to the impact Covid-19 has had on the authorities finances each service has been asked to review their capital strategy and reduce the capital spend for the remainder of this financial year. This is partially due to staffing resources. SCHOOL MODERNISATION PROGRAMME 3.9.20 A briefing on the development of all through schools across the county. CABINET/EMT 8.9.20 Home to school transport, WEPCO special partnership agreement for new schools. Consultation decision for long term empty properties and council tax increases. Revised Highways Capital schemes. Machynlleth Gypsy and traveller site, Transfer of Neuadd Maldwyn, Welshpool. Automobile Palace in Llandrindod Wells, Community Library Partnership and Treasury Management Annual Report. GLOBAL CENTRE FOR RAIL EXCELLENCE (GCRE) 8.9.20 A briefing on the proposed rail excellence testing and training facility neighbouring between South Powys and Neath. Currently in negotiations for the site acquisition. Much work has been done with interested parties, train operators and Universities Engineering department. Testing is currently done in EU or USA so we need s facility in UK and to work on an open market approach across the UK rail network. CARE INSPECTORATE WALES (CIW) CIW will undertake a monitoring visit with Adult and Children’s Services in Powys week commencing 14.09.20. -

Design & Access Statement

DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT Land to the east of Ithon Road (Phase 3, 4 & 5), Llandrindod Wells April 2021 T: 029 2073 2652 T: 01792 480535 Cardiff Swansea E: [email protected] W: www.asbriplanning.co.uk PROJECT SUMMARY LAND TO THE EAST OF ITHON ROAD, LLANDRINDOD WELLS Description of development: Full planning application for residential dwellings and associated works Location: Land to the east of Ithon Road (Phases 3, 4 and 5), Llandrindod Wells Date: April 2021 Asbri Project ref: 20.248 Client: J G Hale Construction Ltd STATEMENT A C CE S S & DE S I G N Asbri Planning Ltd Prepared by Approved by Unit 9 Oak Tree Court Mulberry Drive Mared Jones Dylan Green Cardiff Gate Business Park Name Cardiff Graduate Planner Senior Planner CF23 8RS T: 029 2073 2652 Date April 2021 April 2021 E: [email protected] W: asbriplanning.co.uk Revision A A A PR I L 2 0 2 1 2 CONTENTS LAND TO THE EAST OF ITHON ROAD, LLANDRINDOD WELLS Section 1 Introduction incl./ Brief and Vision 4 Section 2 Site Context and analysis 6 Section 3 Interpretation incl. Opportunities and Constraints 10 Section 4 Design development 12 Section 5 Planning Policy Context 14 Section 6 The Proposal incl. 5 Objectives of Good Design 16 STATEMENT Section 7 Conclusion 22 A C CE S S & DE S I G N A PR I L 2 0 2 1 3 LAND TO THE EAST OF ITHON ROAD, LLANDRINDOD WELLS STATEMENT SITE LOCATION PLAN A C CE S S & DE S I G N A PR I L 2 0 2 1 4 LAND TO THE EAST OF ITHON ROAD, LLANDRINDOD WELLS INTRODUCTION Introduction Vision & Brief 1.1 This Design and Access Statement (DAS) has been 1.6 The vision for the proposal on land to the east of Ithon prepared on behalf of J G Hale Construction to accompany Road is to create a residential development that incorporates the full planning application for residential development the best facets of design and ensures that placemaking and associated works on land to the east of Ithon Road. -

Regional Hubs: Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers

Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers Bridgend The Bridgend hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Archbishop McGrath Catholic School Brynteg School Bryntirion Comprehensive School Coleg Cymunedol Y Dderwen Cynffig Comprehensive School Maesteg School Pencoed Comprehensive School Porthcawl Comprehensive School Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Llangynwyd For further information on the Bridgend hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Simon Gray: [email protected] Cardiff The Cardiff hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Pre-16 provision only Includes post-16 provision Corpus Christi Catholic High Bishop of Llandaff Church in School Wales High School Eastern High School Cantonian High School Mary Immaculate High School Cardiff High School St Illtyd’s Catholic High School Cardiff West Community High School Willows High School Fitzalan High School Llanishen High School Radyr Comprehensive School 27/05/2020 1 St Teilo’s Church in Wales High School Whitchurch High School Ysgol Bro Edern Ysgol Glantaf Ysgol Plasmawr Post-16 provision only Cardiff and Vale College St David’s College For further information on the Cardiff hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Jo Kemp: [email protected] Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire The Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Pre-16 provision only Includes post-16 provision Ysgol Bro Gwaun -

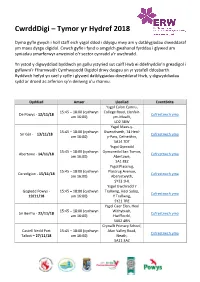

Cwrdddigi – Tymor Yr Hydref 2018

CwrddDigi – Tymor yr Hydref 2018 Dyma gyfle gwych i holl staff eich ysgol ddod i ddysgu mwy am y datblygiadau diweddaraf ym maes dysgu digidol. Cewch gyfle i fynd o amgylch gwahanol fyrddau i glywed am syniadau ymarferwyr arweiniol o'r sector cynradd a'r uwchradd. Yn ystod y digwyddiad byddwch yn gallu ystyried sut caiff Hwb ei ddefnyddio’n greadigol i gyflawni’r Fframwaith Cymhwysedd Digidol drwy dasgau yn yr ystafell ddosbarth. Byddwch hefyd yn cael y cyfle i glywed datblygiadau diweddaraf Hwb, y digwyddiadau sydd ar droed ac arferion sy’n deilwng o’u rhannu. Dyddiad Amser Lleoliad EventBrite Ysgol Calon Cymru, 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn College Road, Llanfair- De Powys - 12/11/18 Cofrestrwch yma am 16:00) ym-Muallt, LD2 3BW Ysgol Maes-y- 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn Gwendraeth, 74 Heol- Sir Gâr - 13/11/18 Cofrestrwch yma am 16:00) y-Parc, Cefneithin, SA14 7DT Ysgol Gynradd 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn Gymunedol San Tomos, Abertawe - 14/11/18 Cofrestrwch yma am 16:00) Abertawe, SA1 8EZ Ysgol Plascrug, 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn Plascrug Avenue, Ceredigion - 15/11/18 Cofrestrwch yma am 16:00) Aberystwyth, SY23 1HL Ysgol Uwchradd Y Gogledd Powys - 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn Trallwng, Heol Salop, Cofrestrwch yma 19/11/18 am 16:00) Y Trallwng, SY21 7RE Ysgol Caer Elen, Heol 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn Withybush, Sir Benfro - 22/11/18 Cofrestrwch yma am 16:00) Hwlffordd, SA62 4BN Crynallt Primary School, Castell Nedd Port 15:45 – 18:00 (cychwyn Afan Valley Road, Cofrestrwch yma Talbot – 27/11/18 am 16:00) Neath, SA11 3AZ DigiMeet – Autumn Term 2018 Here's an excellent opportunity for all your staff to learn more about the latest developments in digital learning.