Ojionuka Arinze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 9(6): 331-342, 2019; Article no.IJECC.2019.026 ISSN: 2581-8627 (Past name: British Journal of Environment & Climate Change, Past ISSN: 2231–4784) Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria Endurance Okonufua1*, Olabanji O. Olajire2 and Vincent N. Ojeh3 1Department of Road Research, Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2African Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in English, OAU and Centre for Space Research and Applications, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. 3Department of Geography, Taraba State University, P.M.B. 1167, Jalingo, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors EO, OOO and VNO designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors OOO and VNO managed the analyses of the study. Author EO managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/IJECC/2019/v9i630118 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Anthony R. Lupo, Professor, Department of Soil, Environmental and Atmospheric Science, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA. Reviewers: (1) Ionac Nicoleta, University of Bucharest, Romania. (2) Neha Bansal, Mumbai University, India. (3) Abdul Hamid Mar Iman, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Malaysia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/48742 Received 26 March 2019 Accepted 11 June 2019 Original Research Article Published 18 June 2019 ABSTRACT The study was conducted in Afikpo South Local Government covering a total area of 331.5km2. Remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) were integrated with multicriteria analysis to delineate the flood vulnerable areas. -

95 Traditional Methods of Social Control in Afikpo

TRADITIONAL METHODS OF SOCIAL CONTROL IN AFIKPO NORTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA, EBONYI STATE SOUTH EASTERN NIGERIA Blessing Nonye Onyima Abstract This paper examined the traditional social control mechanisms in Afikpo North LGA of Ebonyi state, south eastern Nigeria. The rising trend in extraneous crimes and vices like kidnapping, baby factories, drug peddling among others seem to be overwhelming for modern social control mechanisms. This has lent credence to myriads of scholarly suggestions targeted towards making the south eastern Nigerian region a sane society. These suggestions are community policing, use of community vigilante and calls to integrating traditional and modern social control mechanisms. This study employed I86 structured questionnaires and the in-depth interview guide as instruments for data collection anchored on the social bond theory. The researcher made use of descriptive statistics to analyze the questionnaires, the frequency tables and simple percentage was used in presenting and interpreting the quantitative data. The data was also processed using the SPSS, for detailed analysis of the questionnaire. The qualitative data from the in-depth interview was analyzed using the manual thematic content analysis. The study found two groups of effective traditional social control methods (human and non-human traditional social control methods) used to ensure social cohesiveness, order and peaceful inter-human relations in Afikpo North LGA of Ebonyi state. Study respondents expressed preference for human- oriented/managed -

THE AESTHETICS of IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 1996 The composite scene: the aesthetics of Igbo mask theatre Ukaegbu, Victor Ikechukwu http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/2811 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Exeter School of Arts and Design Faculty of Arts and Education University of Plymouth May 1996. 90 0190329 2 11111 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Date .. 3.... M.~~J. ... ~4:l~.:. VICTOR I. UKAEGBU. ii I 1 Unlversity ~of Plymouth .LibratY I I 'I JtemNo q jq . .. I I . · 00 . '()3''2,;lfi2. j I . •• - I '" Shelfmiul(: ' I' ~"'ro~iTHESIS ~2A)2;~ l)f(lr ' ' :1 ' I . I Thesis Abstract THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU An observation of mask performances in Igboland in South-Eastern Nigeria reveals distinctions among displays from various communities. -

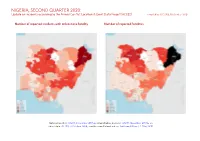

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020

NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 30 October 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 3 October 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 356 233 825 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 246 200 1257 Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 2 Protests 141 1 1 Explosions / Remote Methodology 3 77 67 855 violence Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 75 26 42 Strategic developments 18 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 913 527 2980 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). Development of conflict incidents from June 2018 to June 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 3 October 2020). 2 NIGERIA, SECOND QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 30 OCTOBER 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Complexity As Aesthetics in the Iri-Agha of the Ohafia Igbo People

International Journal of February, 2020 Development Strategies in Humanities, Management and Social Sciences IJDSHMSS p-ISSN: 2360-9036 | e-ISSN: 2360-9044 Vol. 10, No. 1 Complexity as Aesthetics in the Iri-Agha of the Ohafia Igbo People Omeh Obasi Ngwoke A b s t r a c t Department of English Studies, Faculty of Humanities, ery little is known of the diverse forms of African University of Port Harcourt, folklore, especially those with literary and artistic Port Harcourt, Nigeria Vmerit in spite of their pervasive presence within the continent and their unabated practice among the peoples that own them. As part of the efforts in filling this critical gap, this paper examines one of such forms among the Ohafia Igbo people of eastern Nigeria named the Iri-Agha - that is “war dance” in English. The essay's contention is that though a few studies have been carried out on the highly artistic and massively enjoyed dramatic enactment of the indigenous people, no scholarship exists in the area of its complexity of form. Here then lies the focus and significance of this essay which seeks to examine the intricacies of the traditional performance's formal features. The study deploys the method of qualitative ethnography involving close observation and interview of the practitioners of the art in the field collection of primary Keywords: data, and the theory of ethno-poetics in the analysis the Complexity, collected data. Consequently, the study discovers that the Aesthetics, Iri-Agha, Iri-Agha depicts an artistic complexity that emanates from a War, Dance, Drama, seamless combination of materials from the dramatic, the Performance narrative and the poetic arts and a blending of these with resources from the plastic and decorative arts. -

Soil Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government 2 Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

1 SOIL VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF AFIKPO SOUTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT 2 AREA, EBONYI STATE, NIGERIA 3 ABSTRACT 4 Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) integrated with Revised Universal 5 Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) was adopted to estimate the rate of annual soil loss in Afikpo South 6 Local Government. This is important due to the fact that agriculture is the main source of 7 livelihood in the area. The RUSLE factors were computed using data such as rainfall from 8 NIMET, Soil from FAO, elevation from SRTM and Landsat 8 OLI from USGS. The data were 9 used as input in a GIS environment and the annual soil loss was generated using the RUSLE 10 equation. The result shows that the average annual soil loss ranges from 0 to 155,858 ha/ton/yr. 11 It was also observed that soil erosion was predominant in the southern part of Afikpo South LGA 12 due to the presence of steep slopes in the area. The study serves as a preliminary documentation 13 for planning, conservation and management of soil resources in the Local Government. 14 Keywords: Soil Vulnerability, Estimation, RUSLE, Afikpo South, Nigeria 15 16 INTRODUCTION 17 Soil erosion is just the efficient expulsion of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface 18 by the different operators of denudation. It happens in several parts of Nigeria under various 19 land, climatic and soil conditions. Be that as it may, the level of event shifts extensively from one 20 part of the nation to the other (Ofomata, 2015). Similarly varied are the components in charge of 21 the commencement and advancement of erosion, just as the sorts that exist in several parts of the 22 country. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

National Assembly 260 2013 Appropriation

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2013 BUDGET SUMMARY FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES TOTAL TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL CODE MDA OVERHEAD TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL COST ALLOCATION COST =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES - 0252001001 1,062,802,556 434,615,687 1,497,418,243 28,714,910,815 30,212,329,058 HQTRS 0252037001 ANAMBRA/ IMO RBDA 455,494,870 69,652,538 525,147,408 7,223,377,629 7,748,525,037 252038001 BENIN/ OWENA RBDA 310,381,573 48,517,004 358,898,577 2,148,547,575 2,507,446,152 0252039001 CHAD BASIN RBDA 349,481,944 66,930,198 416,412,142 2,090,796,556 2,507,208,698 0252040001 CROSS RIVER RBDA 336,692,834 69,271,822 405,964,656 5,949,000,000 6,354,964,656 0252051001 GURARA WATER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY 17,112,226 70,346,852 87,459,078 167,000,000 254,459,078 0252041001 HADEJIA-JAMAļARE RBDA 384,683,182 53,037,247 437,720,429 5,322,607,552 5,760,327,981 0252042001 LOWER BENUE RBDA 305,996,666 49,183,926 355,180,592 4,684,200,000 5,039,380,592 0252043001 LOWER NIGER RBDA 510,037,910 66,419,289 576,457,199 5,452,950,000 6,029,407,199 0252044001 NIGER DELTA RBDA 509,334,321 77,714,503 587,048,824 4,382,640,000 4,969,688,824 NIGERIA INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT 0252050001 143,297,122 89,122,355 232,419,477 154,000,000 386,419,477 COMMISSION NATIONAL WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE- 0252049001 266,646,342 40,532,007 307,178,349 403,000,000 710,178,349 KADUNA 0252045001 OGUN/ OSUN RBDA 387,437,686 79,556,978 466,994,664 3,500,153,045 3,967,147,709 0252046001 SOKOTO RIMA RBDA 431,782,730 83,609,292 515,392,022 6,827,983,001 7,343,375,023 -

Download 4105.Pdf

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 5, Issue, 10, pp.2949-2959, October, 2013 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE GENDER MAINSTREAMING AND DEVELOPMENT IN (AFRICAN) IGBO TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS SOCIETY: A CRITICAL OPTION FOR THE NEW WORLD ORDER *Okoro, Kingsley Nwannennaya and Osunwokeh, Clement, I. Department of Philosophy and Religion, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki-Nigeria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Gender issues have become a critical concern of all humanity today. The case is that women are marginalized, th more especially in Africa. Thus part of African underdevelopment is attributed to this discrimination. The major Received 10 July, 2013 factor that makes the study of gender problems in Africa complex is that African traditional society, particularly, Received in revised form th the Igbo society of Eastern Nigeria, anchor their development, social organizations and political structure on the 13 August, 2013 their religion(s). So their religious belief defines and controls all social arrangements. However, the picture of Accepted 21st September 2013 th women marginalization in Igbo society seems to be representing the Igbo society of the modern era rather than the Published online 10 October 2013 Igbo of the pre-colonial period. This paper therefore contends that the assumption that women in the Igbo traditional society were sidelined into the private sphere is tinged with historical bias. Thus through sociological Key words: and historical survey, this paper discovers that women have been in the frontline of social development in the Igbo traditional society. It notes also that most positions of power are not inherited rather they are acquired through Gender, Mainstreaming, achievements. -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Perspectives on Nigerian Peoples and Culture

Perspect ives on Nigerian Peoples and Cult ure i ii Perspectives on Nigerian Peoples and Culture Edited by Joh n E. A gaba Chris S. Orngu iii © Department of History, Benue State University, Makurdi, 2016 All rights Reserved. This book is copyright and so no part of it should be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner (Department of H istory, Benue State U niversity, M akurdi). ISBN: 978-978-954-726-5 A Publication of the Department of History, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria. Department of History, BSU Publication Series No. 1, 2016 iv Dedication Our Students v Acknowledgements We acknowledge the contributors for their collective resourcefulness in putting this volume together. We also deeply appr eci at e t h e sch ol ar s w h ose or i gi n al i deas h ave added val u e t o the chapters in this volume. vi Contents Dedication v Acknow;edgements vi Contents vii Foreword ix Chapter One Conceptual Perspectives of Culture Chris Orngu 1 Chapter Two Notable Ethnic Groups in Northern Nigeria Terwase T. Dzeka and Emmanuel S. Okla 7 Chapter Three Notable Ethnic Group in Southern Nigeria Toryina A. Varvar and Faith O. Akor 22 Chapter Four Culture Zones in Nigeria Armstrong M. Adejo and Elijah Terdoo Ikpanor 36 Chapter Five Traditional Crafts and Cultural Festivals in N igeria Emmanuel C. Ayangaor 53 Chapter Six The Evolution of the Nigerian State Saawua G. -

Information Kit for 2015 General Elections

INFORMATION KIT FOR 2015 GENERAL ELECTIONS 1 FOREWARD The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has come a long way since 2011 in making the Nigerian electoral process transparent, as a way of ensuring that elections are free, fair and credible and that they measure up to global best standards of democratic elections. We have done this not only by reforms that have been in the electoral procedures, but also in the way informationon the process is made available for public use and awareness. Even though the yearnings of many Nigerians for a perfect electoral process may not have been fulfilled yet, our reforms since 2011 has ensured incremental improvement in the quality and credibility of elections that have been conducted. Beginning with some of the Governorship elections conducted by INEC since 2013, the Commission began to articulate Information Kits for the enlightenment of the public, especially election observers and journalists who may need some background information in order to follow and adequately undertstand the electoral process. With the 2015 General Elections scheduled to take place nationwide, this document is unique, in that it brings together electoral information about all the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). I am optimistic that this kit will contribute to the body of knowledge about the Nigerian electoral system and enhance the transparency of the 2015 elections. Professor Attahiru Jega, OFR Chairman ACRONYMS AC Area Council Admin Sec Administrative Secretary AMAC Abuja Municipal Area