1996 by Abubakar Hassan Ahmed I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Rural and Community Development in Nigeria: a Case Study of Communities in Abuja Municipal Area Council (Amac)

ASSESSMENT OF RURAL AND COMMUNITY . DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA: 1. A CASE STUDY OF COMMUNITIES IN ABUJA MUNICIPAL AREA COUNCIL (AMAC) FCT-ABUJA .. BY lBllAI-IIM ELIZABET/1 P. REG. NO. 04463322 · .. BEING A DESEllTATION SUBMITTED TO TI-lE I,OSTGRADUATE SCfiOOL, FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, ' DEPf\.RTMEN1' OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTEllNATIONAL RELATIONS, UNIVERSITY OF ABUJA, . IN ·p ARl'IAL FULFILMEN1, OF TI-IE REQUIREMENT FOR TI-IE A WAl{D OF M.SC IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND POLICY ANALYSIS (PAPA). SEPTEMBER, 2011. .. CERTIFICATION This DISSERTATION Assessment of Rural and Community Development in Niger·ia: A Case Study of Communities in Abuja Municipal Area Council (AMAC), FCT Abuja, carried out by IBRAHIM, Elizabeth Pasha Reg. No. 04463322 has been read, corrected and approved as meeting the requirements for the award of Masters of Science Degree (M.Sc) in Public Administration and Policy Analysis in the Department of Politic�.d elations, University of Abuja, Nigeria. --- ------- ---- --- ----- ------ ------ --- , ---- Professor I.E.S. Amdii (Supervisor) .• . oaka Date ( ead ofDepartment) --t)_J-�:------------rr::; �· ��---_· . I'!1 Dr. S.O. Ogbu Date (Ag. Dean, Fac ty a ------ �� - - ----- -- ------ - --- - -- �- ---- -- - - £-:�=�-1= Professor Haruna D. Dlakwa __ ,, (ExternalExaminer) Date ��----- ------------------ _hh�--��-==��-t - ---�------ !?_ ifrofessor F.W. Abdulrahman Date (Dean, PostgraduateSchool) -----·- DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Late Father, Late Sister and late Grandmother, Mr Ishaku I. Pasha, Mrs Gladys Murna M.K. Asso and Mrs Elizabeth Ibrahim who never lived to see what have achieved today. 1 Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I give God Almighty the glory, thanks and praises for giving me wisdom, grace and strength to accomplish this work. -

The Resettlement Policy in Urban Centres: the Case Study of Abuja

THE RESETTLEMENT POLICY IN URBAN CENTRES: THE CASE STUDY OF ABUJA BY TALLE MUSA SA'EED MASTERS PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION NO: 95428091 BEING A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAi, RELATIONS, UNIVERSITY OF ABUJA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE AWARD OF A MASTER'S DEGREE IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION (MPA) APRIL 1999 CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this project has been presented by Talle Musa Sa'eed and has been approved accordingly. '°' J oo Supervisor Date I DR. IRO IRO UKE ftJ!i;Pk Head of PROFESSOR UMAR M. BIRARIIZ'. External Examiner Date DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the following people: Alhaji Danladi Ismaila - Chief of Karshi Alhaji Saidu Makaman Karshi - My father Hajiya Fatima Maichibi Saidu - My mother Late Alhaji Talle Keffi - My guardian Late Alhaji Abdulkadir Mamman - My cousin 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge the efforts of all the people who have in one way or the other contributed to the successful pursuit of this project. However, I would like to first of all, express profound gratitude to the Almighty Allah (SWT) for graciously enabling both my physical and mental condition to undertake the entire programme and the project in particular. Then my sincere appreciation go to my research supervisor, Dr. I.I. Uke who greatly guided and assisted me through, and even on his sick bed! Indeed, may the Almighty God fasten his complete recovery . I also like to thank Mallam Mohammed Haruna Funky, Mallam Idris 0. Jibrin and Mr. Martins Oloja, former Editor of Abuja Newsday, all of whom assisted me with relevant materials in the cause of the research. -

PAGES 1,6,7 THUR 8-7-2021.Indd

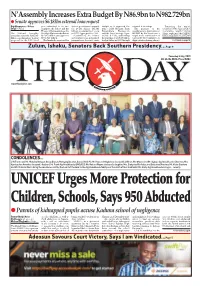

N’Assembly Increases Extra Budget By N86.9bn to N982.729bn Senate approves $6.183bn external loan request Deji Elumoye and Udora year submitted to its two federal government's request budget as it approved the external borrowings. Presenting the report, Orizu in Abuja chambers, the Senate and the for $6.183 billion (N2.343 2022 - 2024 Medium Term The passage of the Chairman of the Appropriation House of Representatives, by trillion) as external borrowing Expenditure Framework supplementary Appropriation Committee, Senator Barau The National Assembly President Muhammadu Buhari in 2021 Appropriation Act. and the Fiscal Strategy Paper Bill 2021 by the Senate was a Jibrin, explained that N45.63 yesterday raised the N895.842 by N87.9 billion and approved Nonetheless, the federal (MTEF & FSP), authorising sequel to the consideration of billion required for COVID-19 billion supplementary budget N982.729 billion. government has intensified the funding of a N5.26 trillion a report by the Committee on proposal for the 2021 fiscal The Senate also approved the preparations for next year's budget deficit in 2022 through Appropriation during plenary. Continued on page 12 Zulum, Ishaku, Senators Back Southern Presidency...Page 8 Thursday 8 July, 2021 Vol 26. No 9586. Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T R U N T H & R E ASO CONDOLENCES... L-R (Front row): Mr. Mobolaji Balogun; Group Deputy Managing Director, Access Bank Plc, Mr. Roosevelt Ogbonna; deceased’s children, Ms. Ofovwe and Mr. Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede; Chairman, Mrs. Ajoritsedere Awosika; deceased's husband, Mr. Frank Aig-Imoukhuede; GMD/CEO, Mr. Herbert Wigwe; deceased’s daughter, Mrs. -

Survey of the Current Distribution and Status of Bacterial Blight and Fungal Diseases of Cassava in Guinea

A Research Article in AJRTC (2011) Vol. 9 No. 1: Pages 1-5 Survey of the current distribution and status of bacterial blight and fungal diseases of cassava in Guinea B.A. Bamkefa1, E.S. Bah2 and A.G.O. Dixon3 1International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, PMB 5320, Ibadan, Nigeria. 2Institut de Recherche Agronomique de Guinée, Guinea. 3Sierra Leone Agricultural Research Institute, Freetown Corresponding Author: B.A. Bamkefa Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 02/08/2010; accepted:15/11/2010 Abstract A survey was carried out of 86 cassava fields in the lowland savanna; humid forest, mid-altitude savanna, and lowland humid savanna agroecological zones of Guinea. Each field was assessed for the incidence and severity of cassava bacterial blight (CBB), cassava anthracnose disease (CAD), Cercospora leaf blight (CLB), and brown leaf spot (BLS). Samples of diseased leaves were collected and used to identify associated pathogens. CBB was present in all the four major ecozones. The disease was observed in 88.88% of the fields visited in the humid forest. For other ecozones, results were 70.5% (mid-altitude savanna zone), 73.07% (lowland humid savanna), and 77.7% (low-land savanna). Anthracnose disease was observed in the humid forest and lowland humid savanna zones, but not in either of the others. CAD was observed in 11.11% of the fields visited in the humid forest, and in 19.23% in the lowland humid savanna. The disease was not observed in either of the others. CLB and BLS were observed in all the zones; however, the severity of both diseases was generally low and they did not seem to pose a serious threat to cassava tuberous root yield. -

Appropriation Bill

Federal Government of Nigeria APPROPRIATION BILL 0228026001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - OKWE ONUIMO CODE LINE ITEM AMOUNT 22021002 HONORARIUM & SITTING ALLOWANCE 85,608 22021003 PUBLICITY & ADVERTISEMENTS 85,608 22021004 MEDICAL EXPENSES 85,608 22021006 POSTAGES & COURIER SERVICES 85,608 22021007 WELFARE PACKAGES 85,608 22021008 SUBSCRIPTION TO PROFESSIONAL BODIES 85,608 22021014 ANNUAL BUDGET EXPENSES AND ADMINISTRATION 85,608 22021029 MONITORING ACTIVITIES & FOLLOW UP 85,608 22021030 PROMOTION, RECRUITMENT & APPOINTMENT 85,608 2203 LOANS AND ADVANCES 85,608 220301 STAFF LOANS & ADVANCES 85,608 22030105 CORRESPONDENCE ADVANCES 85,608 23 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE 46,136,167 2301 FIXED ASSETS PURCHASED 27,795,667 230101 PURCHASE OF FIXED ASSETS - GENERAL 27,795,667 23010112 PURCHASE OF OFFICE FURNITURE AND FITTINGS 8,357,000 23010129 PURCHASE OF INDUSTRIAL EQUIPMENT 19,438,667 2302 CONSTRUCTION / PROVISION 5,000,000 230201 CONSTRUCTION / PROVISION OF FIXED ASSETS - GENERAL 5,000,000 23020101 CONSTRUCTION / PROVISION OF OFFICE BUILDINGS 5,000,000 2303 REHABILITATION / REPAIRS 13,340,500 230301 REHABILITATION / REPAIRS OF FIXED ASSETS - GENERAL 13,340,500 23030121 REHABILITATION / REPAIRS OF OFFICE BUILDINGS 13,340,500 TOTAL PERSONNEL 29,200,837 TOTAL OVERHEAD 7,276,651 TOTAL RECURRENT 36,477,488 TOTAL CAPITAL 46,136,167 TOTAL ALLOCATION 82,613,655 0228026001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - OKWE ONUIMO CODE PROJECT NAME TYPE AMOUNT TBICNNE 01019118 PROCUREMENT OF EQUIPMENT FOR PACKAGING AND LABELLING OF PRODUCTS FOR NEW 19,438,667 -

Rnment of Nigeria 2008 Budget Amendment 2008

2008 BUDGET RNMENT OF NIGERIA AMENDMENT 2008 BUDGET =N= TOTAL MINISTRY OF ENERGY 151,952,463,046 0430000 MINISTRY OF ENERGY (POWER) TOTAL ALLOCATION: 24,993,484,580 Classification No. EXPENDITURE ITEMS 043000001100001 TOTAL PERSONNEL COST 521,540,942 043000001100010 SALARY & WAGES - GENERAL 466,462,682 043000001100011 CONSOLIDATED SALARY 466,462,682 043000001200020 BENEFITS AND ALLOWANCES - GENERAL 0 043000001200021 RENT TOPSAL 043000001300030 SOCIAL CONTRIBUTION 55,078,260 043000001300031 NHIS 22,031,304 043000001300032 PENSION 33,046,956 043000002000100 TOTAL GOODS AND NON - PERSONAL SERVICES - GENERAL 1,064,022,248 043000002050110 TRAVELS & TRANSPORT - GENERAL 360,390,550 043000002050111 LOCAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 213,753,755 043000002050112 INTERNATIONAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 146,636,795 043000002060120 TRAVELS & TRANSPORT (TRAINING) - GENERAL 39,446,416 043000002060121 LOCAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 14,351,416 043000002060122 INTERNATIONAL TRAVELS & TRANSPORT 25,095,000 043000002100200 UTILITIES - GENERAL 47,522,527 043000002100201 ELECTRICITY CHARGES 11,285,243 043000002100202 TELEPHONE CHARGES 24,667,060 043000002100203 INTERNET ACCESS CHARGES 5,150,000 043000002100204 SATELLITES BROADCASTING ACCESS CHARGES 2,756,000 043000002100205 WATER RATES 2,205,000 043000002100206 SEWAGE CHARGES 1,459,224 043000002150300 MATERIALS & SUPPLIES - GENERAL 196,804,367 043000002150301 OFFICE MATERIALS & SUPPLIES 146,937,391 043000002150302 LIBRARY BOOKS & PERIODICALS 10,611,555 043000002150303 COMPUTER MATERIALS & SUPPLIES 14,100,188 043000002150304 PRINTING -

ANALYSIS of SPATIAL PATTERN of SETTLEMENTS in the FEDERAL CAPITAL TERRITORY of NIGERIA USING VECTOR-BASED GIS DATA Jinadu A

FUTY Journal of the Environment, Vol. 3 No.1, July 2008 1 © School of Environmental Sciences, Federal University of Technology, Yola – Nigeria.. ISSN 1597-8826 ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERN OF SETTLEMENTS IN THE FEDERAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF NIGERIA USING VECTOR-BASED GIS DATA Jinadu A. M Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria. Phone: +2348034052367, Email: [email protected] Abstracts Human settlements are important, seemingly static but dynamic, features of the cultural landscape that have attracted several studies due to the important role they play in human life. This paper examined the spatial distribution of settlements in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria. The analysis uses vector based GIS data derived from the 1989 political map of the FCT. Map composition was done with ArcView 3.2a software and the nearest neighbour statistics was computed using the pattern analysis function of Ilwis 3.0 software. The result of the quadrat count analysis yielded a variance mean ratio of 1.34 to show that the settlements of the FCT were clustered in space as opposed to the subjective findings of some authors, which suggested that the settlements were evenly spread. Analysis of the degree of clustering reveals that 51 per cent of all settlement pair has a separation of less than four kilometres, 63 per cent has a separation of less than five kilometres, 79 per cent has less than six kilometres while 97 per cent has a separation of less then nine kilometres. It was thus found out that, for 80 per cent of all settlements in the point map, one nearest neighbour can be found within a radius of 2 kilometres. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria 2016 APPROPRIATION ACT

Federal Republic of Nigeria 2016 APPROPRIATION ACT Federal Government of Nigeria SUMMARY BY MDAs 2016 APPROPRIATION ACT TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL NO CODE MDA TOTAL CAPITAL PERSONNEL OVERHEAD RECURRENT ALLOCATION 1. 0252 FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES 6,332,795,809 886,260,632 7,219,056,441 46,081,121,423 53,300,177,864 6,332,795,809 886,260,632 7,219,056,441 46,081,121,423 53,300,177,864 SUMMARY BY FUNDS 2016 APPROPRIATION ACT TOTAL NO CODE FUND ALLOCATION 1. 021 MAIN ENVELOP - PERSONNEL 6,332,795,809 2. 022 MAIN ENVELOP - OVERHEAD 886,260,632 3. 031 CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT FUND MAIN 46,081,121,423 53,300,177,864 FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES 2016 APPROPRIATION ACT TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL NO CODE MDA TOTAL CAPITAL PERSONNEL OVERHEAD RECURRENT ALLOCATION 1. 0252001001 FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES - HQTRS 1,267,112,688 273,665,579 1,540,778,267 24,331,214,462 25,871,992,729 2. 0252002001 NIGERIA HYDROLOGICAL SERVICE AGENCY 201,669,054 38,935,101 240,604,155 403,127,100 643,731,255 3. 0252037001 ANAMBRA/ IMO RBDA 383,532,543 38,935,100 422,467,643 1,681,229,914 2,103,697,557 4. 0252038001 BENIN/ OWENA RBDA 301,729,810 30,605,254 332,335,064 489,500,000 821,835,064 5. 0252039001 CHAD BASIN RBDA 369,997,029 35,576,963 405,573,992 1,012,000,000 1,417,573,992 6. 0252040001 CROSS RIVER RBDA 326,008,128 38,388,662 364,396,790 1,436,626,837 1,801,023,627 7.