Forest Fuel Harvest in Stands of Lodgepole Pine Have Also Been Studied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Industry Safety and Health Standard Part 51. Logging

MIOSHA-STD-1135 (02/17) For further information 18 Pages Ph: 517-284-7740 www.michigan.gov/mioshastandards DEPARTMENT OF LICENSING AND REGULATORY AFFAIRS DIRECTOR’S OFFICE GENERAL INDUSTRY SAFETY STANDARDS Filed with the Secretary of State on February 15, 1970, (as amended May 15, 1974) (as amended October 28, 1976) (as amended May 17, 1983) (as amended November 15, 1989) (as amended June 17, 1996) (as amended August 5, 2014) (as amended February 23, 2017) These rules take effect immediately upon filing with the Secretary of State unless adopted under section 33, 44, or 45a(6) of 1969 PA 306. Rules adopted under these sections become effective 7 days after filing with the Secretary of State. (By authority conferred on the director of the department of licensing and regulatory affairs by sections 16 and 21 of 1974 PA 154, MCL 408.1016 and 408.1021, and Executive Reorganization Order Nos. 1996-2, 2003-18 2003-1, 2008-4, and 2011-4, MCL 408.1016, 408.1021, 445.2001, 445.2011, 445.2025, and 445.2030) R 408.15102, R 408.15111, R 408.15114, R 408.15117, R 408.15120, R 408.15125, R 408.15127, R 408.15130, R 408.15131, R 408.15144, R 408.15146, R 408.15148, R 408.15150, R 408.15165, and R 408.15166 of the Michigan Administrative Code are amended, and R 408.15117a, R 408.15117b, R 408.15146a and R 408.15146b are added, as follows: GENERAL INDUSTRY SAFETY AND HEALTH STANDARD PART 51. LOGGING Table of Contents: GENERAL PROVISIONS ........................................... -

Wood Industries Classifieds

Multitek 20/25 Bar Saw Firewood Processor with heated cab and 30 foot conveyor. 2733 hours and 300 hours on new JD engine. Machine is in great condition. 4, 6, and 8 way wedges $52,000. Call 203-331-7628 Wood Industries Classifeds Cost of Classified Ads: $70 per column inch if paid in advance, $75 per column inch Fabtek 2 Roller with if billed thereafter. Repeating ads are $65 per column inch if paid in advance, $70 per computer and wiring. Videotape of it working column inch if billed thereafter. Firm deadline for ads is the 15th of the month preceding available. Recently in publication. To place an ad call (315) 369-3078; FAX (315) 369-3736. the woods. $14,500. Please note: The Northern Logger neither endorses nor makes any representation or Timbco/Valmet 415, 425, 445 used Finals; Timbco guarantee as to the quality of goods or the accuracy of claims made by the advertisers undercarriages, under- appearing in this magazine. Prospective buyers are urged to take normal precautions carriage parts, booms, when conducting business with firms advertising goods and services herein. cylinders; and so much more available. Shipping available/Credit Cards FOR SALE Accepted. 740-201-8228 THE NORTHERN LOGGER | SEPTEMBER 2019 43 FOR SALE 2010 Barko 495 TMS Pkg w/Self-Propell Carrier..$119,500 2014 CAT 545C 7000 Hours ..........................$119,500 2014 CAT 521B 3300 Hours .........................$199,500 #84923 - 2017 Bandit BTC300 #76233 - 2005 CAT TK711 2004 Hyundai 140 Hydraulic Thumb............... $32,500 Mower/Stump Grinder, 315 HP, Track Harvester, CAT Diesel 2016 JCB 411 2300 Hours ............................. -

Productivity and Cost-Efficiency of Bundling Logging Residues at Roadside Landing

Original scientific paper – Izvorni znanstveni rad Productivity and Cost-Efficiency of Bundling Logging Residues at Roadside Landing Juha Laitila, Marica Kilponen, Yrjö Nuutinen Abstract – Nacrtak The aim of this case study was to clarify the productivity and cost of a system based on bun- dling logging residues at the roadside landing with the forwarder-mounted logging residue bundler. In order to find the bundling productivity, a set of time studies was carried out, in which several working techniques were tested and evaluated. The cost-efficiency of the roadside bundling system was compared with the conventional bundling system, wherein the logging of residue logs is made directly in the terrain and, after bundling, the logging residue logs are forwarded to the roadside landing with a forwarder. The harvesting cost (bundling and for- warding) of the extracted wood biomass to the roadside landing was calculated for bundling systems using time study data obtained from this study and productivity models and cost parameters acquired from the literature. The productivity of roadside bundling ranged from 48 to 53 logging residue logs per effective working hour (E0h), depending on the working technique used, and the mean time required to produce one logging residue log ranged from 83.6 to 92.3 seconds (E0h). The harvesting costs of the logging residue logs (€/m3) at the roadside landing were 11.5–13.7 €/m3 for the system based on bundling in terrain and 10.8–17.7 €/m3 for the system based on bundling at the roadside landing, when the forwarding distance was in the range 100–600 m and the removal of logging residues was in the range 30–90 m³/ha (m3 = solid cubic metre). -

Productivty and Cost of a Cut-To-Length Commercial Thinning

PRODUCTIVTY AND COST OF A CUT-TO-LENGTH COMMERCIAL THINNING OPERATION IN A NORTHERN CALIFORNIA REDWOOD FOREST By Kigwang Baek A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Resources: Forestry, Watershed, & Wildland Sciences Committee Membership Dr. Han-Sup Han, Committee Chair Dr. Daniel Opalach, Committee Member Dr. John-Pascal Berrill, Committee Member Dr. Alison O’Dowd, Program Graduate Coordinator May 2018 ABSTRACT PRODUCTIVTY AND COST OF A CUT-TO-LENGTH COMMERCIAL THINNING OPERATION IN A NORTHERN CALIFORNIA REDWOOD FOREST Kigwang Baek Cut-to-length (CTL) harvesting systems have recently been introduced to the redwood forests of California’s north coast. These machines are being used to commercially thin dense redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) stands which tend to form clumps of stems that vigorously sprout from stumps after a harvest. One of the challenges is to avoid damaging residual trees which can decrease productivity, increase costs, and lower the market value of trees. The goal of this study was to evaluate the productivity and costs associated with CTL systems used in a redwood forests and use that data to develop equations for predictions. Time and motion study methods were used to calculate the productivity of a harvester and forwarder used during the winter and summer seasons. Regression equations for each machine were developed to predict delay-free cycle (DFC) times. Key factors that influenced productivity for the harvesters was tree diameter and distance between harvested trees. Productivity for the harvesting ranged from 28.8 to 35.6 m3 per productive machine hour (PMH). -

Mechanized Tree Planting in Sweden and Finland: Current State and Key Factors for Future Growth

Article Mechanized Tree Planting in Sweden and Finland: Current State and Key Factors for Future Growth Back Tomas Ersson 1 ID , Tiina Laine 2 and Timo Saksa 2,* 1 School of Forest Management, SLU/Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 73921 Skinnskatteberg, Sweden; [email protected] 2 Luke/Natural Resources Institute Finland, Latokartanonkaari 9, 00790 Helsinki, Finland; [email protected] * Correspondence: timo.saksa@luke.fi; Tel.: +358-29-532-4834 Received: 29 March 2018; Accepted: 26 May 2018; Published: 21 June 2018 Abstract: In Fennoscandia, mechanized tree planting is time-efficient and produces high-quality regeneration. However, because of low cost-efficiency, the mechanization of Fennoscandian tree planting has been struggling. To determine key factors for its future growth, we compared the operational, planning, logistical, and organizational characteristics of mechanized planting in Sweden and Finland. Through interviews with planting machine contractors and client company foresters, we establish that mechanized tree planting in Sweden and Finland presently shares more similarities than differences. Some notable differences include typically longer planting seasons in Sweden, and a tendency towards two-shift operation and less frequent worksite pre-inspection by contractors in Finland. Because of similar challenges, mechanized planting in both countries can improve cost-efficiency through education of involved foresters, flexible information systems, efficient seedling logistics, and continued technical development of planting machines. By striving to have multiple client companies, contractors can reduce their operating radii and increase their machine utilization rates. Above all, our results provide international readers with unprecedented detailed and comprehensive figures and characteristics of Swedish and Finnish mechanized tree-planting activities. -

September/October 1991

A Publication of the New York Forest Owners Association September/October 1991 I THE NEW YORK FOREST OWNER FOREST OWNER A publication of the New York Forest Owners Association Editorial Committee: Betty Densmore,Richard Fox, Alan Knight, Mary McCarty, Norm Richards, and Dove Tober . VOL. 29, NO.5 Materials submitted for publication should be addressed to: R. Fox,R.D. #3, Box 88, Moravia, New York 13118.Articles, artwork and photos are invited and are normally returned ofter use. Thedeadline for submission is 30 days prior to publication in November. OFFICERS & DIRECTORS Please address all membership and. change of address requests to P.O. Box 180.fairport Stuart McCarty , President N.Y. 14450. OOEast Avenue Rochester, NY 14618 (716)381-6373 Charles Mowatt, 1st Vice President PO Box 1182 Savona, NY 14879 Robert M. Sand, Recording Secretary 300Church Street Odessa, NY 14869-9703 Angus Johnstone, Treasurer PO Box 430 East Aurora, NY 14052 John C. Marchant, Executive Director 45Cambridge Court Fairport, NY 14450 (716)377-7906 Deborah Gill, Administrative Secretary P.O. Box 180 Fairport, NY 14450 (716)377-7906 Executive Office POBox 180 Fairport, NY 14450 (716)377-6060 1992 Rohert A. Hellmann. Brockport Alan R. Knight, Candor stuart McCarty, Rochester Charles Mowatt. Savona NFC Niagara Frontier, 1990 1993 David J. ColUgan, Buffalo AFC Niagara Frontier, 1990 VernerC. Hudson. Elbridge AFC Allegany Foothills, 1989 Mary S. McCarty. Rochester WFL Western Finger Lakes, 1988 Sanford Vreeland. Springwater CAy Coyuga, 1985 DonaldJ. Wagner, Utica TIO Tioga, 1986 1994 THRIFT.. Tug Hill Resources, Investment for Tomorrow, 1982 Norman Richards, Syracuse CNY Central New York, 1991 Robert M. -

Predesignatedskid Trails 2.2.1.3 Reforestation

Chapter 2—Alternatives 2.2.1.2 Timber Yarding Ground-based yarding In ground-based yarding, a machine travels to the logs and pulls them to the landing. The machines used for skidding are diverse and can have wheels or tracks. Trees and logs are removed from the woods using rubber- tired skidders, tracked skidders, or forwarders. The skidders yard the trees to the landing by lifting the front end of the logs off the ground. Skidders travel on skid trails that are designated and approved by the BLM. A feller-buncher fells and bunches trees mechanically. The typical feller-buncher is track mounted. Some must move from tree-to-tree for felling, while others use a boom to fell multiple trees from a single position. The feller-buncher bundles trees for a skidder to pick up and move to a landing. A forwarder is a rubber-tired machine that typically works with a harvester. Harvesters move through the stand felling, delimbing, bucking, and bunching trees selected for harvest. Forwarders travel into the stands on the slash created by the harvester. They load the logs piled by the harvester and carry them to the road where they are ofF-loaded. The logs carried by a forwarder do not touch the ground during travel. Ground-based yarding is generally limited to slopes of 35% or less. After harvest is complete, skid trails and landings not needed for future management would be ripped, seeded, and mulched. Skyline-cable yarding Skyline-cable yarding uses steel cables to pull logs to the landing. A stationary machine, or yarder, would be located on the road and would pull logs up to the landing with one end of the log suspended. -

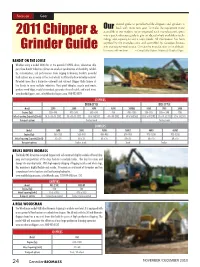

2011 Chipper & Grinder Guide

Focus on Gear annual guide to portable/mobile chippers and grinders is Our back with more new gear. To make the equipment more accessible to our readers, we’ve organized each manufacturer’s specs 2011 Chipper & into a quick-reference guide to give an idea of what’s available in tech- nology and capacity to suit a user’s needs. All information has been supplied by the manufacturers and assembled by Canadian Biomass into one easy-to-read source. Contact the manufacturer or local dealer Grinder Guide for more information. – Compiled by Stefanie Wallace & Heather Hager BANDIT ON THE LOOSE Whether using a model 2400 disc or the powerful 3590XL drum, whole-tree chip- pers from Bandit Industries deliver an excellent combination of durability, reliabil- ity, customization, and performance. From logging to biomass, Bandit’s powerful feed systems use as many as five feed wheels to efficiently draw in limby material. Patented items like a distinctive cuttermill and optional Chipper Knife System al- low Beasts to serve multiple industries. They grind shingles, recycle yard waste, produce wood chips, create bio-sawdust, generate coloured mulch, and much more. www.banditchippers.com, [email protected], 800-952-0178 CHIPPERS DRUM-STYLE DISC-STYLE Model 2290 2590 3090 3590 3590XL 1850 1900 2400 Engine (hp) 250–440 375–540 535–630 700 700–1200 250–325 535 or 540 700 Infeed opening [capacity] (inch) 24.5 x 26.25 [20] 30 x 26.25 [22] 30 x 36 [24] 48 x 30 [30] 48 x 36 [36] 20.5 x 18 [18] 23 x 19.5 [19] 29 x 24 [24] Transport options Trailer, track Trailer, track GRINDERS Model 1680 2680 3680 3680T 4680 4680T Engine (hp) 160–325 365–440 400–800 630–800 875–1200 875–1200 Infeed opening [capacity] (inch) 52 x 24 60 x 24 60 x 35 60 x 35 60 x 45 60 x 45 Transport options Trailer, track Track Trailer BRUKS MOVES BIOMASS The Bruks 805 forwarder-mounted chipper with self-contained chip bin enables off-road chip- ping and transportation of the chips back to a roadside trailer. -

Modelling Harvester-Forwarder System Performance in a Selection

Journal of Forest Engineering • 7 Modelling Harvester-Forwarder uneven-aged management are being introduced to achieve these conditions. One approach, the selec System Performance in a tion method of regeneration, is being used in many Selection Harvest areas of the western United States and Canada to develop and maintain uneven aged conditions within J.F. McNeel1 the stand and to rapidly create late successional USD A Forest Service conditions within treated stands. Seattle, USA Harvests based on the group selection method D. Rutherford of regeneration remove a representative number of University of British Columbia stems within specific diameter classes in a number of Vancouver, Canada small areas within the stand. Harvests are made at time intervals ranging from 10 to 40 years to promote regeneration within the stand and to insure a diver ABSTRACT sity of growth within the stand. A harvester - forwarder system was studied in a Harvesting systems used for group selection selection harvest operation conducted in an interior harvests require more control over machine opera forest stand composed of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga tions during the harvest to minimize residual stand menziesii), Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), and damage and site impacts. However, the harvest Grand fir (Abies grandis). A time-study analysis was system options available to forest managers are rela used to develop models for predicting individual tively limited. Manual felling and processing re machine productivity over time for both the har quire excessive time and labour, while conventional vester and forwarder involved in the study. Analy mechanized systems which harvest tree-length ma sis indicates that harvester productivity (13.85 m3 terial often produce more residual stand damage per SMH) closely matched forwarder production than is acceptable from a management standpoint. -

G-Series Forwarders from John Deere

G-SERIES FORWARDERS 910G / 1010G / 1110G / 1210G / 1510G / 1910G WORK SMARTER AND HARDER MOVING KEEP PRODUCTIVITY NG FORWARD. We’ve put some serious thought into our G-Series Forwarders. But the real brainpower behind our latest models is you. Through our Customer Advocate Group (CAG), we collected invaluable input from loggers just like you — the ones who live it every day. Then we spent thousands of hours testing the machines until we got them exactly right. These forward-thinking forwarders are loaded with improvements that boost performance and long-term durability, including increased power and torque. An upgraded Intelligent Boom Control (IBC) system option for more precise boom control. And, as always, a host of enhancements that help deliver more uptime and efficiency, while lowering daily operating costs. Built on more than 180 years of groundbreaking innovation. Backed by over a half-century of experience in the woods. And designed with proven components to withstand the toughest environments. The G-Series will make you rethink what a forwarder can accomplish for your operation. 4 WON’T LET UP — OR LET YOU DOWN Lower the boom on downtime. When you work in remote areas, downtime is never an option. G-Series Forwarders are built forest-tough, with durable booms, axles, and electrical components. Dependable booms Robust axles Tough brakes Optional IBC system features Duraxle™ heavy-duty (HD) bogie Hydraulically actuated, oil-immersed, sensors that dampen boom axles — available in the 1210G, 1510G, multi-disc service brakes provide movements, protecting boom and 1910G — are designed to carry dependable stopping power. structures, for longer life. -

H024 Cocept Design for Teleoperation of John Deere Feller

PO Box 1127 Rotorua 3040 Ph.: + 64 7 921 1883 Fax: + 64 7 921 1020 Email: [email protected] Web: www.fgr.nz Programme: Harvesting and Logistics Project Number: 3.2 Report No.: H044 Milestone 2 In-forest debarking: a review of the literature Glen Murphy Research Provider: GE Murphy & Associates Ltd Rotorua, New Zealand Date: 13 May 2020 Leadership in forest and environmental management, innovation and research TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 3 Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 5 LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................................................. 5 Bark and bark characteristics ...................................................................................................... 5 Advantages and disadvantages of in-forest debarking ................................................................ 8 Safety issues associated with in-forest debarking ....................................................................... 9 Harvesting system and equipment impacts on bark loss ........................................................... 11 Technologies for removing bark in-forest or at satellite yards ................................................... -

CTL Cable-Assisted Harvesting

CTL Cable-assisted Harvesting Matthew Mattioda Vice President CTL Systems Chief Forester Miller Timber Services 1 Discussion Overview • Cable-assisted system types • Static • Dynamic • Ponsse harvester-forwarder system • Bear, Elephant King, Herzog Synchrowinch • Why does cable-assistance work? • Underlying mechanisms, pressure reduction, horizontal and vertical benefits • CTL Layout Tips • Corridors, winch, landing/roads, weather, tree characteristics, etc. • Pricing • Benefits and challenges with CTL • Management implications, take-away messages 2 System Types • Static Line System • One line remains fixed relative to ground • Tree or machine anchor • Common in thinning applications (short logs up to 28’) • Fully integrated winch 3 System Types • Dynamic Line System • Two lines moving • Machine anchor • Excavator-based harvesting machine and anchor • Clearcut application • Radio-controlled anchor machine • Harvesting often followed by tethered grapple skidder or skyline system 4 Ponsse Harvester-Forwarder System Bear Harvester Elephant King Forwarder 5 Ponsse Harvester-Forwarder System Bear Harvester Elephant King Forwarder • Approximately 52,470 lbs. • Approximately 52,250 lbs. • 322 hp Mercedes-Benz diesel • 275 hp Mercedes-Benz diesel engine engine • 51,706 lbf tractive force • 53,954 lbf tractive force • Versatile platform for difference • Load capacity of 44,092 lbs. cranes and heads • 8W Bogies, articulated chassis • 8W Bogies, articulated chassis 6 Ponsse Synchrowinch • ~9/16 inch, 1,150 foot high compacted construction line •