Calling Citizens, Improving the State: Pakistan's Citizen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making of New Provinces in Punjab and Its Implications on Federal Structure of Pakistan

Pakistan Political Science Review Vol. 1 No. 1 (2019) MAKING OF NEW PROVINCES IN PUNJAB AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON FEDERAL STRUCTURE OF PAKISTAN Muhammad Faisal University of the Punjab, Lahore Abstract:- Pakistan is a federal state having four provinces. Punjab is the largest province of the country with regard to population diversity. The ethno-regional, socio-economic, linguistic and institutional diversity in this region is bifurcated. The province is ethno-regionally and linguistically divided; socio-economically gulfed and institutionally marginalized. This unequal and marginalized development in the past led to the spectrum of intra-regional movement for making of new provinces in Punjab. The intra-regional movements are based on ethnic lines supported by the regional political parties. Political elites in the mainstream political parties advocate/advocating administrative, institutional, bureaucratic as well as ethnic baseline for making of new provinces in the province of Punjab. Based on the historical trends, this paper will address the constitutional, administrative, political, socio-economic, ethno-linguistic and institutional baselines for making of new provinces in Punjab. This restructuring will affect the federation of Pakistan in constitutional, administrative and institutional way. It will also study the implications of restructuring of Punjab on federal structure of Pakistan. This paper will be an important document for further policymaking in this realm. Keywords: Pakistan, Punjab, Federation, Political Parties and Elites, Ethno-regionalism Introduction Pakistan incorporated a federal form of government from its very beginning. After attaining independence from the British colonial masters; the leadership of the state and its territorial units, political parties and the state institutions hailed to adopt the federal form of government. -

PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT This report is published in collaboration with DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protesting Hazara Killings, Press Club, Islamabad, Pakistan, April 2012 © Mahvish Ahmad Layout and maps: Allan Lind Jørgensen, ALJ Design Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-517-2 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-518-9 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Mona Kanwal Sheikh, ph.d., postdoc [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Pakistan – a stage for regional rivalry 7 The Baloch insurgency and geopolitics 25 Militant groups in FATA and regional rivalries 31 Domestic politics and regional tensions in Pakistan-administered Kashmir 39 Gilgit–Baltistan: sovereignty and territory 47 Punjab and Sindh: expanding frontiers of Jihadism 53 Urban Sindh: region, state and locality 61 3 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Abstract What connects China to the challenges of separatism in Balochistan? Why is India important when it comes to water shortages in Pakistan? How does jihadism in Punjab and Sindh differ from religious militancy in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)? Why do Iran and Saudi Arabia matter for the challenges faced by Pakistan in Gilgit–Baltistan? These are some of the questions that are raised and discussed in the analytical contributions of this report. -

Pakistan Provinces and Divisions Northerna Areas

PAKISTAN PROVINCES AND DIVISION C H I N A NORTHERrN4CHINA AREAS IA MM U KA; I I I I i 5 p,.,,., * ISLAMABAD If HHITO)lf . ^:,K,°/ • "' -. PUNJAB / 1, sK / "( i!ALUCHISTAN I RAN b SIND AR A B I A N SEA ,. ".. ri) o NATIONAL NUTRITION SURVEY 1985 - 87 REPORT NUTRITION DIVISION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HEALTH GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN 1988 REPORT OF THE NATIONAL NUTRITION SURVEY 1985-87, PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS 'FOREWORD ............................................ (i) PREFACE ............................................. (lii) ACKNOWLEDEGEMENT .................................... (iv) 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................... (vi) 1.1 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................ (viii) 2. INTRODUCTION 2.1 GENERAL INFORMATION .............................. .. 2.1.1. Geographical 2.1.2. Literacy 2.1.3. Agriculture 2.1.4. Trends In Agricultural Production 2.1.5. Health 2.1.6. Primary Health Care 2.2. NUTRITIONAL STATUS .............................. 6 2.2.1 General 2.2.2. Malnutrition in Children 2.2.3. Breast Feeding 2.2.4. Bottle Feeding 3. THE NATIONAL NUTRITION SURVEY 1985/87 3.1 BACKGROUND ..................................... 8 3.2 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................ ;.......... 8 3.3 SAMPLING ....................................... 9 3.3.1 Universe 3.3.2 Stratification Plan 3.3.3 Sampling Frame 3.3.4 Sample Design 3.3.5 Sample Size and its Allocation 3.4 WEIGHTING ....................... .............. 11 2.5 METHODOLOGY .................................... 13 3.r.1 Household Survey 3.5.2 Dietary Survey 3.5.3 Clinical Survey 3.5.4 Anthropometric Examination 3.5.5 Biochemical Survey 3.6 CLASSIFICATION OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS ............ 15 4. RESULTS 4.1. CHILDREN UNDER 5 4.1.1 Anthropometry of Children under 5 ...... 19 4.1.2 Age & Sex Distribution .................. 20 .... -

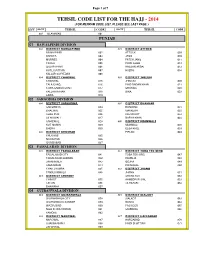

Tehsil Code List for the Hajj

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ - 2014 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Hydrologic Evaluation of Salinity Control and Reclamation Projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan a Summary

Hydrologic Evaluation of Salinity Control and Reclamation Projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan A Summary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1608-Q Prepared in cooperation with the West Pakistan Water and Powt > Dei'elofunent Authority under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development Hydrologic Evaluation of Salinity Control and Reclamation Projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan A Summary By M. ]. MUNDORFF, P. H. CARRIGAN, JR., T. D. STEELE, and A. D. RANDALL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF ASIA AND OCEANIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1608-Q Prepared in cooperation with the West Pakistan Water and Power Development Authority under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1976 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THOMAS S. KLEPPE, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Hydrologic evaluation of salinity control and reclamation projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan. (Contributions to the hydrology of Asia and Oceania) (Geological Survey water-supply paper; 1608-Q) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.13:1608-Q 1., Reclamation of land Pakistan Indus Valley. 2. Salinity Pakistan Indus Valley. 3. Irrigation Pakistan Indus Valley. 4. Hydrology Pakistan Indus Valley. I. Mundorff, Maurice John, 1910- II. West Pakistan. Water and Power Development Authority. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. -

Directorate General Health Services Punjab

0 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES PUNJAB. D.G.H.S Office [DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES, PUNJAB] Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. DGHS, Punjab. 1. 042 99201139-40 (PSO) 99201139-40 ( P.A ) 2. 042 Fax 99201142 99238505 3. DHS (HQ) 042 99201141 DHS (EPI) 99201143 4. 042 99202812 Fax 99200405 ADG (Dengue) (EP&C) 99203235 042 5. Fax 99203235 DHS (P&D) 6. 042 99203793 7. DHS (MIS) 042 99205510 Program Manager( NCD) 8. 042 9. DHS (Dental). 042 99203751 Director (Pharmacy) 99201145 042 10. 99204622 DHS (CDC) 11. 042 99200970 DHS (TB). 35408894 12. 042 Fax 99203750 Director (Accounts). 13. 042 99202487 Additional Director (Admn). 99200987 14. 042 Fax 99201095 36118382 Res Additional Director (EPI) 15. 042 99200535 Additional Director (Malaria ) 16. 042 99202970 A. D (F&N/NCD) 99203749 042 17. Fax. 99204190 (Micronutrient) 99204014 18. 042 36290201 Fax Addl. Director (IRMNCH) 99205330-26 19. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 1 Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. Addl. Director-I, IRMNCH 99200982 20. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 P.M Hepatitis 21. 042 99204129 Addl. Director (MS&DC) 22. 042 99203505 Usman Ghani 23. 042 99200969 Additional Director (H.E). Media Manager 24. 042 99200969 Additional Director (TB-DOTS) 25. 042 99203750 Transport Manager, TMO 26. Workshop 042 35155845 27. (Supt.TPT) Budget & Accounts Officer 28. 042 99203487 Additional Director (Homeo) Shahid (Homeo Dr) 29. 042 99204191 Litigation Officer 30. Mr.Imran Ur Rehman 042 99200983 Computer Programer 31. 042 99200990 G.M (MSD) 35758336 32. 042 35873989 99201257 33. Bacteriologist 042 99200108 PD (HIV/AIDS). -

Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program

SFG3075 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Public Disclosure Authorized Development Department, Government of Sindh Final Report December 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Final Report Executive Summary Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, GOS and Agriculture Department GOS with grant assistance from DFID funded multi donor trust fund for Nutrition in Pakistan are planning to undertake Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition (MSAN) Project. ESMF Consultant1 has been commissioned by Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning to fulfil World Bank Operational Policies and to prepare “Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) for MSAN Project” at its inception stage via assessing the project’s environmental and social viability through various environmental components like air, water, noise, land, ecology along with the parameters of human interest and mitigating adverse impacts along with chalking out of guidelines, SOPs, procedure for detailed EA during project execution. The project has two components under Inter Sectoral Nutrition Strategy of Sindh (INSS), i) the sanitation component of the project aligns with the Government of Sindh’s sanitation intervention known as Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) in 13 districts in the province and aims to increase the number of ODF villages through certification while ii) the agriculture for nutrition (A4N) component includes pilot targeting beneficiaries for household production and consumption of healthier foods through increased household food production in 20 Union Councils of 4 districts. Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) This component of the project will be sponsored by Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, Sindh and executed by Local Government Department (LGD) through NGOs working for the Inter-sectoral Nutrition Support Program. -

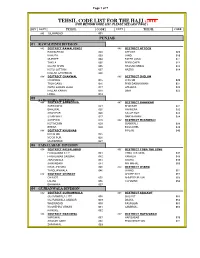

Tehsil Code List 2014

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ -2016 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface Bureau of Statistics has been issuing this publication since 1972. The present edition is the 43rd in the series. It provides important statistics in respect of social, economic and financial sectors of the economy at aggregate as well as sectoral levels. This publication contains data on almost all sectors of the Provincial economy with their break-up by Tehsil, District & Division as far as possible. Eight tables on Monthly Electricity and Gas Consumption, Number of Zoo, Number of Bulldozers, Small and Mini Dams, Recognized Slaughter Houses and two provisional tables on population census 2017 are also added in this issue. It includes some national data on important subjects like Major Crops, Foreign Trade, Labour Force & Employment, National Accounts, Population, Price and Transport etc. It contains a 'Statistical Abstract' which gives a comparative picture of information on almost all Socio- Economic sectors of Pakistan and the Punjab. Key findings of Multiple Indicator Cluster Servey (MICS): 2014 of some of the Socio-Economic Indicators are also included in this edition viz-a-viz Education, Health, Housing and Socio-Economic Development by district. Every effort has been made to include the latest available data in this publication. It is hoped that this publication will be useful to the policy makers, planners, researchers, govt. departments and other users of Socio-Economic data in public as well as private sector. I am thankful to various Provincial Departments / Agencies / Federal Ministries / Divisional/District offices for supplying the required data. Without their co-operation, it would have not been possible to release this publication in time. -

PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT This report is published in collaboration with DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protesting Hazara Killings, Press Club, Islamabad, Pakistan, April 2012 © Mahvish Ahmad Layout and maps: Allan Lind Jørgensen, ALJ Design Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-517-2 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-518-9 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Mona Kanwal Sheikh, ph.d., postdoc [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Pakistan – a stage for regional rivalry 7 The Baloch insurgency and geopolitics 25 Militant groups in FATA and regional rivalries 31 Domestic politics and regional tensions in Pakistan-administered Kashmir 39 Gilgit–Baltistan: sovereignty and territory 47 Punjab and Sindh: expanding frontiers of Jihadism 53 Urban Sindh: region, state and locality 61 3 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Abstract What connects China to the challenges of separatism in Balochistan? Why is India important when it comes to water shortages in Pakistan? How does jihadism in Punjab and Sindh differ from religious militancy in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)? Why do Iran and Saudi Arabia matter for the challenges faced by Pakistan in Gilgit–Baltistan? These are some of the questions that are raised and discussed in the analytical contributions of this report. -

Government of Pakistan Climate Change Division National Disaster Management Authority Monsoon Weather Situation Report 2014 Dated: 15September 2014

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CLIMATE CHANGE DIVISION NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY MONSOON WEATHER SITUATION REPORT 2014 DATED: 15SEPTEMBER 2014 RIVERS RESERVOIRS (Reading 1020hrs) LOSSES / DAMAGES River / MAX Conservation Actual Observations RESERVOIR Today (Feet) Structure Design Forecast for Forecasted Level (Feet) Capacity In Flow Out Flow Next 24hrs Flood Level Tarbela 1,550.00 1,547.37 (Cusecs) (thousand (thousand (Inflow) (Inflow) cusecs) cusecs) Mangla 1,242.00 1,242.00 RIVER INDUS (Reading 1020hrs) RAINFALL (MM) PAST 24 HOURS Lahore Tarbela 1,500,000 86.0 48.3 80 – 90 Below Low 56 Lahore (A/P) 32 Kotli 15 (Shahdara) No Significant Kalabagh 950,000 93.7 85.9 -do- Shadiwal 41 Ravi Syphon 31 Marala 14 Details Attached at Annex “A” Change Chashma 950,000 76.7 70.7 -do- -do- Mangla 39 Parachinar 31 Jhelum 14 Alexandra Lahore (Misri Taunsa 1,000,000 62.2 46.3 -do- -do- 38 25 Sara-e-Alamgir 09 Bridge Shah) Guddu 1,200,000 260.9 238.9 270 R 410 Medium Sargodha (City) 38 Palandri 17 Gujrat 09 Sukkur 900,000 150.5 96.5 160 R 230 Low Mandibahauddin 37 Sialkot (A/P) 16 Kasur 08 No Significant Lahore Kotri 850,000 24.5 0.0 -do- Sargodha (A/P) 35 15 Joharabad 08 Change (ShahiQilla) RIVER KABUL (Reading 1020hrs) METEOROLOGICAL FEATURES NOTES No Significant FLOOD WARNINGS Nowshera - 15.4 15.4 Below Low Change RIVER JHELUM (Reading 1020hrs) Yesterday’s Shallow Trough of westerly wave over Kashmir 1. As per Hydrology Directorate, WAPDA, Mangla 1,060,000 71.0 69.9 60 – 75 Below Low continues to persist. -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs.