Pakistan Provinces and Divisions Northerna Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making of New Provinces in Punjab and Its Implications on Federal Structure of Pakistan

Pakistan Political Science Review Vol. 1 No. 1 (2019) MAKING OF NEW PROVINCES IN PUNJAB AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON FEDERAL STRUCTURE OF PAKISTAN Muhammad Faisal University of the Punjab, Lahore Abstract:- Pakistan is a federal state having four provinces. Punjab is the largest province of the country with regard to population diversity. The ethno-regional, socio-economic, linguistic and institutional diversity in this region is bifurcated. The province is ethno-regionally and linguistically divided; socio-economically gulfed and institutionally marginalized. This unequal and marginalized development in the past led to the spectrum of intra-regional movement for making of new provinces in Punjab. The intra-regional movements are based on ethnic lines supported by the regional political parties. Political elites in the mainstream political parties advocate/advocating administrative, institutional, bureaucratic as well as ethnic baseline for making of new provinces in the province of Punjab. Based on the historical trends, this paper will address the constitutional, administrative, political, socio-economic, ethno-linguistic and institutional baselines for making of new provinces in Punjab. This restructuring will affect the federation of Pakistan in constitutional, administrative and institutional way. It will also study the implications of restructuring of Punjab on federal structure of Pakistan. This paper will be an important document for further policymaking in this realm. Keywords: Pakistan, Punjab, Federation, Political Parties and Elites, Ethno-regionalism Introduction Pakistan incorporated a federal form of government from its very beginning. After attaining independence from the British colonial masters; the leadership of the state and its territorial units, political parties and the state institutions hailed to adopt the federal form of government. -

PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT This report is published in collaboration with DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protesting Hazara Killings, Press Club, Islamabad, Pakistan, April 2012 © Mahvish Ahmad Layout and maps: Allan Lind Jørgensen, ALJ Design Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-517-2 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-518-9 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Mona Kanwal Sheikh, ph.d., postdoc [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Pakistan – a stage for regional rivalry 7 The Baloch insurgency and geopolitics 25 Militant groups in FATA and regional rivalries 31 Domestic politics and regional tensions in Pakistan-administered Kashmir 39 Gilgit–Baltistan: sovereignty and territory 47 Punjab and Sindh: expanding frontiers of Jihadism 53 Urban Sindh: region, state and locality 61 3 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Abstract What connects China to the challenges of separatism in Balochistan? Why is India important when it comes to water shortages in Pakistan? How does jihadism in Punjab and Sindh differ from religious militancy in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)? Why do Iran and Saudi Arabia matter for the challenges faced by Pakistan in Gilgit–Baltistan? These are some of the questions that are raised and discussed in the analytical contributions of this report. -

Production and Marketing of Camel Products in Semi-Desert and Desert Areas of Pakistan

Pakistan J. Agric. Res. Vol. 26 No. 2, 2013 PRODUCTION AND MARKETING OF CAMEL PRODUCTS IN SEMI- DESERT AND DESERT AREAS OF PAKISTAN Abid Hussain*, Khalid Mahmood Aujla* and Sonila Hassan** Abstract:- The study was designed to analyze the production and marketing of camel products in the semi-desert and desert areas of Pakistan. It is based on cross-sectional data collected through simple random sampling technique in April, 2011 from 220 camel farmers and 17 market intermediaries. It is found that both camel farmers and market intermediaries were less educated. It is observed that markets for camel milk, meat, hides and hair are less established in semi desert and desert areas of the country. Mean production of milk per farm household was 5.4 and 6.5 liters per day in summer and winter seasons, respectively; however, none of the surveyed farmers reported milk sale. During last one year, sales of camel hides and hair were reported by few farmers (6% each). Mean purchase price of camel hides reported by shopkeepers in nearby town markets were higher than village level prices by 74.6 % and even more in case of hair. This is an indicative of camel farmers' exploitation by the village dealers. Mean quantity of hair sales was about 20 kg per farm per annum. Camel hair are also used by the farmers for making ropes, rugs and blankets, but all these byproducts are not marketed. Shares of farmers in the consumer rupee for camel meat, milk, hides and hair were about 61%, 75%, 52% and 26%, respectively. -

The Spectrum of Beta-Thalassemia Mutations in Couples Referred for Chorionic Villus Sampling at Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3265 The Spectrum of Beta-thalassemia Mutations in Couples Referred for Chorionic Villus Sampling at Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur Uffan Zafar 1 , Kamran Naseem 2 , Muhammad Usman Baig 3 , Zain Ali Khan 4 , Fariha Zafar 5 , Saba Akram 6 1. Radiology Department, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK 2. Radiology Department, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur , PAK 3. Medicine, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur, PAK 4. Gastroenterology, Pakistan Kidney and Liver Institute and Research Centre, Okara, PAK 5. Community Medicine, Quaid E Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK 6. Medical Ward, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK Corresponding author: Uffan Zafar, [email protected] Abstract Introduction The prevalence of beta-thalassemia mutations is different in various castes, regions, and ethnic groups. By knowing this prevalence, we can conduct a targeted screening of only the high-risk population and only for the specific mutations that are prevalent in each group. Objective The purpose of this study was to determine the regional, caste-wise, and ethnic spectrum of beta- thalassemia mutations in couples referred for a prenatal diagnosis. Methods A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at the thalassemia unit, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur, from October 1, 2015, to May 15, 2018. After obtaining informed consent, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) was performed in 144 women having a gestational age of 12 to 16 weeks. We took blood samples of the couples. A chromosomal analysis for 13 mutations was done at Punjab Thalassaemia Prevention Programme (PTPP), Lahore. -

Situation Analysis of Reproductive Health of Adolescents and Youth in Pakistan

1 Situation Analysis of Reproductive Health of Adolescents and Youth in Pakistan December 2019 i The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. Population Council 3rd Floor, NTC Building (North), Sector F-5/1 Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: +92 51 920 5566 Fax: +92 51 282 1401 Email: [email protected] http://www.popcouncil.org ii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................. VII ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... VIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ IX CHAPTER- 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY .................................................................................... 1 Background ................................................................................................................................................... -

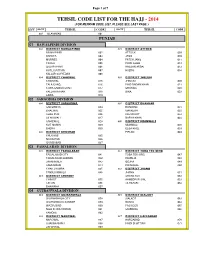

Tehsil Code List for the Hajj

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ - 2014 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Hydrologic Evaluation of Salinity Control and Reclamation Projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan a Summary

Hydrologic Evaluation of Salinity Control and Reclamation Projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan A Summary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1608-Q Prepared in cooperation with the West Pakistan Water and Powt > Dei'elofunent Authority under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development Hydrologic Evaluation of Salinity Control and Reclamation Projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan A Summary By M. ]. MUNDORFF, P. H. CARRIGAN, JR., T. D. STEELE, and A. D. RANDALL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF ASIA AND OCEANIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1608-Q Prepared in cooperation with the West Pakistan Water and Power Development Authority under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1976 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THOMAS S. KLEPPE, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Hydrologic evaluation of salinity control and reclamation projects in the Indus Plain, Pakistan. (Contributions to the hydrology of Asia and Oceania) (Geological Survey water-supply paper; 1608-Q) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.13:1608-Q 1., Reclamation of land Pakistan Indus Valley. 2. Salinity Pakistan Indus Valley. 3. Irrigation Pakistan Indus Valley. 4. Hydrology Pakistan Indus Valley. I. Mundorff, Maurice John, 1910- II. West Pakistan. Water and Power Development Authority. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. -

Directorate General Health Services Punjab

0 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES PUNJAB. D.G.H.S Office [DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES, PUNJAB] Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. DGHS, Punjab. 1. 042 99201139-40 (PSO) 99201139-40 ( P.A ) 2. 042 Fax 99201142 99238505 3. DHS (HQ) 042 99201141 DHS (EPI) 99201143 4. 042 99202812 Fax 99200405 ADG (Dengue) (EP&C) 99203235 042 5. Fax 99203235 DHS (P&D) 6. 042 99203793 7. DHS (MIS) 042 99205510 Program Manager( NCD) 8. 042 9. DHS (Dental). 042 99203751 Director (Pharmacy) 99201145 042 10. 99204622 DHS (CDC) 11. 042 99200970 DHS (TB). 35408894 12. 042 Fax 99203750 Director (Accounts). 13. 042 99202487 Additional Director (Admn). 99200987 14. 042 Fax 99201095 36118382 Res Additional Director (EPI) 15. 042 99200535 Additional Director (Malaria ) 16. 042 99202970 A. D (F&N/NCD) 99203749 042 17. Fax. 99204190 (Micronutrient) 99204014 18. 042 36290201 Fax Addl. Director (IRMNCH) 99205330-26 19. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 1 Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. Addl. Director-I, IRMNCH 99200982 20. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 P.M Hepatitis 21. 042 99204129 Addl. Director (MS&DC) 22. 042 99203505 Usman Ghani 23. 042 99200969 Additional Director (H.E). Media Manager 24. 042 99200969 Additional Director (TB-DOTS) 25. 042 99203750 Transport Manager, TMO 26. Workshop 042 35155845 27. (Supt.TPT) Budget & Accounts Officer 28. 042 99203487 Additional Director (Homeo) Shahid (Homeo Dr) 29. 042 99204191 Litigation Officer 30. Mr.Imran Ur Rehman 042 99200983 Computer Programer 31. 042 99200990 G.M (MSD) 35758336 32. 042 35873989 99201257 33. Bacteriologist 042 99200108 PD (HIV/AIDS). -

Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program

SFG3075 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Public Disclosure Authorized Development Department, Government of Sindh Final Report December 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Final Report Executive Summary Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, GOS and Agriculture Department GOS with grant assistance from DFID funded multi donor trust fund for Nutrition in Pakistan are planning to undertake Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition (MSAN) Project. ESMF Consultant1 has been commissioned by Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning to fulfil World Bank Operational Policies and to prepare “Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) for MSAN Project” at its inception stage via assessing the project’s environmental and social viability through various environmental components like air, water, noise, land, ecology along with the parameters of human interest and mitigating adverse impacts along with chalking out of guidelines, SOPs, procedure for detailed EA during project execution. The project has two components under Inter Sectoral Nutrition Strategy of Sindh (INSS), i) the sanitation component of the project aligns with the Government of Sindh’s sanitation intervention known as Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) in 13 districts in the province and aims to increase the number of ODF villages through certification while ii) the agriculture for nutrition (A4N) component includes pilot targeting beneficiaries for household production and consumption of healthier foods through increased household food production in 20 Union Councils of 4 districts. Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) This component of the project will be sponsored by Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, Sindh and executed by Local Government Department (LGD) through NGOs working for the Inter-sectoral Nutrition Support Program. -

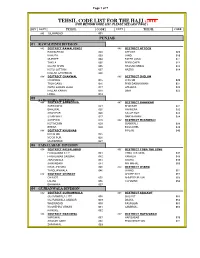

Tehsil Code List 2014

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ -2016 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

MONSOON UPDATE Pakistan

MONSOON UPDATE Pakistan Issue 2 | 28 July - 2 August 2013 This report identifies the current trends, events, and short-term forecast associated with the 2013 monsoon season. OVERVIEW • Weather forecasts indicate a countrywide monsoon spell over the next week with potential heavy impacts between 1 and 4 August. There is a need to monitor the flood impact situation in regions traditionally prone to flash and riverine floods. • The Pakistan Metrological Department has issued flash flood warnings for rain affected areas of Balochistan and Dera Ghazi Khan Division in Punjab. Water channels in the catchments of rivers Chenab and Ravi in Punjab and Kabul in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) may attain medium to high flood levels. • The Space and Upper Atmospher e Research Commission (SUPARCO) indicates the snow cover in 2013 is higher compared with 2008 to 2012, with a corresponding impact on snowmelt. Higher temperatures could cause a rise in river flows. • Water reservoirs continue to fill up comparatively earlier than in previous years, thereby limiting flood impact mitigation options. • Rivers Indus, Chenab, Kabul and Swat are flowing at higher than normal flood levels. MONSOON EVENTS AND IMPACT summer months should be seen in the wider context of snowmelt Rainfall: Last week was characterized by hot and humid and precipitation. Experts estimate 10 per cent of the average conditions with scattered rains. The Pakistan Meteorological runoff is caused by rainfall along the Indus plains. Department (PMD) issued a flash warning for north-eastern River floods: Rivers Indus, Chenab, Kabul and Swat are in Punjab along rivers Chenab and Ravi catchments. low flood. -

Calling Citizens, Improving the State: Pakistan's Citizen

CALLING CITIZENS, IMPROVING THE STATE: PAKISTAN’S CITIZEN FEEDBACK MONITORING PROGRAM, 2008 – 2014 SYNOPSIS In early 2008, Zubair Bhatti, administrative head of the Jhang district in Pakistan’s Punjab province, recognized the need to reduce petty corruption in the local civil service—a problem that plagued not only Punjab but also all of Pakistan. He began to contact citizens on their cell phones to learn about the quality of the service they had received. Those spot checks became the basis for a social audit system that spanned all 36 districts in Punjab by 2014. The provincial government outsourced much of the work to a call center, which surveyed citizens about their experiences with 16 different public services. The data from that call center helped district coordination officers identify poorly performing employees and branches, thereby enhancing the capability of the government to improve service delivery. By early 2014, the province was sending about 12,000 text messages daily to check on service quality. More than 400,000 citizens provided information between the beginning of the initiative and 2014. Known as the Citizen Feedback Monitoring Program, the Punjab’s social audit system became the template for similar innovations in other provinces and federal agencies in Pakistan. Mohammad Omar Masud drafted this case study based on interviews conducted in Punjab, Pakistan, in January and March 2014. Case published February 2015. INTRODUCTION investigation into the behavior of the accused In March 2008, an irate government official district official. But he worried that most of walked into the office of Zubair Bhatti, district Jhang’s 3.3 million residents had no similar coordination officer (DCO)1 of Jhang district, in opportunity for redress.