Building Science Digest 014 Air Flow Control in Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Vapor Migration and Condensation Control in Buildings 2

HPAC Info-dex 2 Engineering Basics he articles in this section were selected by HPAC’s Engineering Editor based on their generic and fundamental nature. Engineering Basics T is intended to be used by engineers, contractors, and facility managers 2 to brush up on engineering fundamentals across a wide range of subjects pertaining to mechanical systems design, building science, and product selection. This year’s selections are as follows: 72 “Water Vapor Migration and Condensation Control in Buildings”—The basics of psychrometric analysis of moisture conditions, including evaluation of vapor barriers and other construction features, and internal and external moisture sources. Examples help guide the discussion of this complex topic. William G. Acker 89 “BACnet: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions”—Answers to frequently asked questions about BACnetE provide invaluable information for building automation system designers, owners, and operators. A primer on the revolutionary development in the building automation and controls industry. By H. Michael Newman Circle 350 on Reader Service Card June 1998 HPAC Heating/Piping/AirConditioning 71 MOISTURE CONTROL Water Vapor Migration and 2 Condensation Control in Buildings The basics of water vapor analysis and control By WILLIAM G. ACKER, pressure). Thus the water vapor lustrated in Equations 4 and 5. President, diffusion is from inside to outside. The inside and outside vapor Acker & Associates, In warmer climates with short pressures can be determined from Green Bay, Wis. heating seasons, the water vapor test data or by using typical psy- drive is from outside to inside due chrometric data for that region. If ater vapor is the gaseous to the drying effect of indoor air there is concern over the amount form of water and is an in- conditioning. -

Insulation and Your Home: Fact

Insulation And Your Home: Fact Sheet Health Considerations Environmental & Occupational Health Assessment Program September 2014 You may be thinking about adding new insulation to your existing home if your home is drafty, or you are looking for ways to save money on energy costs. There are many different types of insulation products in the market place, and many different ways to insulate a house. The type of insulation you choose and the way it is installed may affect your health. The goal of this fact sheet is to help you to become an informed buyer. You will learn to examine three things that can impact your health: 1. Chemical ingredients 2. How dampness and temperature extremes affect your insulation choices 3. Why using an experienced installer is so important. This fact sheet focuses on the most commonly used insulation products in existing houses in the Northeast: synthetic polymer foams like spray polyurethane foam (SPF), mineral wool or fiberglass batts, and blown in cellulose. If you are building a new house or addition, there may be additional insulation products for you to consider. Connecticut Department of Public Health 410 Capitol Avenue, Hartford, CT 06066 http://www.ct.gov/dph Insulation and Your Home: Health Considerations September 2014 Page 2 Exposure to some insulation products can cause 1. Ingredients certain health effects if the product is mis- Many building materials including thermal handled, mis-applied, or if the wrong product is insulation contain fire retardants. Certain classes used in certain environments. Common of insulation products may also contain symptoms may include irritated, itchy, watery, or chemical additives such as colorants, blowing burning sensation of the eyes, nose, or throat, or agents, catalysts, and binding agents. -

Quick Start Guide

The Watchdog900 Quick Start Guide Seaira Global • 14021 NC Highway 50 • Surf City, NC 28445 www.seairaglobal.com WatchDog 900 Quick Start Guide • Prepare Crawl Space for Installation • Tips for Dehumidifier Installation • Operating Instructions • Benefits of a Dehumidifier • Common Terms • Parts Diagram • Trouble Shooting • Submit Warranty • Additional Resources While you’re waiting for your new dehumidifier to arrive, here are a few topics to keep in mind. How to Prepare Your Crawl Space for Installation If you decide to install your dehumidifier in a crawl space, there are a few steps you need to take prior to installation. 1. First, you will need clean out any debris that may be cluttering up the crawl space. This will make sure that there are no hidden problems such as cracks in the foundation. It will also ensure that the vapor barrier can be installed properly. In addition, cleaning out any unnecessary items will make it much easier to move around in the crawl space. Being able to move around more easily is useful for a hassle free installation, as well as for future maintenance that may need to be done. 2. After the crawl space is clear, you will need to inspect it for any potential issues so they can be fixed prior to installation. For instance, you may notice signs of pests or rodents in the crawl space. The crawl space could also show signs of structural issues, such as damaged floor joists or girders. Most importantly, you need to ensure that all signs of excess moisture are taken care of. -

Oregon Residential Energy Code Rev

Oregon Residential Energy Code Rev. March 2005 • No. 15 Moisture Control Measures This pamphlet is one in a series that describes residential sheets may serve as vapor retarders for unfaced insul- energy conservation requirements of the Oregon ation. Certain paints are formulated to act as vapor Residential Specialty Code and the Structural Specialty retarders. Check with your building official to be sure Code for Group R buildings three stories and less in paints are locally accepted. height. Other pamphlets in this series may be obtained from Oregon Dept of Energy at www.oregon.gov/energy/ Figure 1 shows the diffusion process and how vapor or local building departments or from Oregon Building retarders work. Codes Division. Wall vapor retarders Moisture control measures required by the Oregon Residential Energy Code include vapor retarders in walls, Energy code requires a one-perm vapor retarder in floors, and ceilings without attics and a ground cover in walls. Faced insulation may meet both R-value and vapor crawl spaces and below slabs in heated spaces. Section retarder requirements. When unfaced batts or blown-in drawings or written specifications that accompany the batts are used, a vapor retarder must be provided. Vapor plans must show moisture control measures. retarder paints or polyethylene sheets are common wall vapor retarders. Along with damp-proofing and ventilation requirements, moisture control reduces moisture problems Floor vapor retarders in homes and multifamily buildings. A one-perm formulated vapor retarder is also required on floors. The vapor retarder requirement is often met by Vapor retarder requirements using exterior grade plywood or strand board sheathing Vapor retarders reduce moisture condensation within for the floor. -

RREAL's Installation Manual for Solar Thermal Panels (Also Known As “Solar Powered Furnace/SPF”)

SPF Installation Manual Rural Renewable Energy Alliance (RREAL) MADE 2330 Dancing Wind Road SW, Suite 2 IN Pine River, MN 56474, USA MN [email protected] 218-587-4753 www.rreal.org All Rights Reserved 2010 Version 1.10 Table of Contents Figures Safety Warning............................................ 2 1. Fastening Mounting Rails to Structure.... 5 Important Concerns................................... 2 2. SPF Penetration Areas.................................. 6 3. Silicone Location on Starter Collar........... 7 Parts Definitions........................................ 3 4. Installation of Starter Collar....................... 7 Bill of Materials.......................................... 4 5. Installation of Thermistor........................... 7 Additional Materials................................... 4 6. Hang SPF on Mounting Rails..................... 8 1) Select Location........................................ 5 7. Silicone Location on AI Stint..................... 8 2) Hang Mounting Rails.............................. 5 8. Insulation and Back Draft Dampers......... 9 3) Make Penetrations................................... 6 9. Wiring Diagram............................................ 10 10. Extrusion Cut Location............................ 13 4) Prepare to Hang Panel............................ 7 11. Portrait Mounting Rails............................ 14 5) Hang First Panel....................................... 8 12. Landscape Mounting Rails........................ 15 6) Hang Additional Panels.......................... 8 13. -

Fire Resistant, Self-Adhering Membrane Air & Vapor Barriers

MANUFACTURER’S GUIDE SPECIFICATIONS SECTION 072713 FIRE RESISTANT, SELF-ADHERING MEMBRANE AIR & VAPOR BARRIERS 900 Hensley Lane • Wylie TX 75098 • 800-527-7092 • www.carlisleccw.com XXXXXX 03.27.15 Carlisle and Sure-Seal are trademarks of Carlisle. ©2015 Carlisle. Rev. 9/9/14 Project: SECTION 07 27 13 FIRE RESISTANT, SELF-ADHERING MEMBRANE AIR & VAPOR BARRIERS PART 1 GENERAL 1.01 SECTION INCLUDES A. A self-adhered membrane and accessory products of fire-resistant composition for use as an air and vapor barrier in exterior walls. B. Materials and installation to bridge and seal the following air leakage pathways and gaps: 1. Connections of the walls to the roof air barrier 2. Connections of the walls to the foundations 3. Seismic and expansion joints 4. Openings and penetrations of window frames, door frames, store front, curtain wall 5. Barrier pre-cast concrete and other envelope systems 6. Door frames Piping, conduit, duct and similar penetrations 7. Masonry ties, screws, bolts and similar penetrations 8. All other air leakage pathways through the walls 1.02 RELATED SECTIONS A. Section 03 30 00 - Cast-In-Place Concrete [NOTE TO SPECIFIER: Require that backup concrete be free of fins, protrusions and large holes] B. Section 04 20 00 - Unit Masonry [NOTE TO SPECIFIER: When concrete masonry unit (CMU) block walls are to receive Air & Vapor Barrier materials it is critical to address surface preparation issues in this section. Due to the method of installation of the CMU, generally from the inside out, the most critical surfaces to receive the Air & Vapor Barrier materials are neglected and not tooled properly. -

Thermal and Moisture Protection: Keeping the Weather out Internet Course

Rich Text Editor,editor1 http://www.licensetobuild.com/web-class/controls/?mt=coursemanagem... Thermal and Moisture Protection: Keeping the Weather Out Internet Course Learning Objectives Summarize the key elements (either natural or mechanical) of a properly ventilated structure. List and describe at least three specific installation techniques and/or materials that contribute to a properly constructed roof system. Outline at least one design strategy based on "best practices" for the construction of buildings in areas with high humidity. Identify and implement proven methods that will effectively divert moisture from the foundation of a structure. Keeping the Weather Out Protecting buildings from weather and moisture related problems is important for all building professionals. In areas of high humidity, (and ALL Florida counties are considered "warm humid counties" by the Florida Building Code: Energy Conservation 301.2), it is even more important that builders, their employees, and their subcontractors use “Best Practice” procedures to carefully install thermal and weather resistant components. Because of the potential for loss due to consumer complaints and claims, it makes sense for contractors to be trained in moisture control for the homes and buildings they are constructing or renovating. Major performance objectives. One objective of a building envelope system is to provide moisture control. Construction of a building envelope system needs to incorporate methods and materials that prevent or minimize the impact of moisture intrusion. The photo below shows typical damage caused by poorly installed or maintained building envelope components! Too often, exterior shells are simply sealed up without regard for proper installation of house- wraps, flashing and ventilation. -

Installation Manual

Carbon Heating Film • Easy to install. • Can be used as a sole room heating source (when cover at list 70% of the floor). • Does not circulate pollutants, dust, dirt, allergens or dry air. • May be installed on wall, ceiling, under laminate, engineered wood floors or tile. • Brings soothing warmth to specific rooms or cold areas. • Reduces energy up to 60% compared to forced air heating systems. • Maintenance free, strong and durable. • Complements your home heating system making rooms more comfortable. Read through this entire manual before starting installation. • All electrical connections must be made by a licensed electrician in accordance with national and local codes and standards. • Always join multiple heating film lines in parallel ONLY (never in series). • Always make sure to check the heating film before, during, and after installation of the floor covering. • Each thermostat requires a dedicated circuit at the breaker box. • Must not be installed in damp or wet areas as defined by the National Electrical Code. • Do not fold or wrinkle the heating film, walk on it unnecessarily, or drop heavy or sharp objects on it. • Never overlap the heating film. • Do not install electrical wires or pipes in the floor with the film. • Be sure underlayment contains no cellulose. • Install film only when room temperature is above freezing. • Leave a 6-inch space between film and fireplaces, chimneys, or hot water pipes. • Never use any type of insulation material on top of the heating film. • Do not install the healing mats directly over a foil backed insulation material. • When installing carpet a low tog underlay should be installed followed by a good quality hessian backed carpet. -

Vapor Barrier Interior Primer Sealer 1060-1200

Vapor Barrier Interior Primer Sealer 1060-1200 Previously ICI Paints PREP & PRIME™ VAPOR BARRIER Interior Water-Based Primer Sealer DESCRIPTION SPECIFICATION A premium quality latex primer sealer and vapor barrier for interior Color: walls and ceilings. It reduces loss of interior moisture through the White (tintable, limit 4 oz/gal) walls to help maintain insulation efficiency and guard against exterior paint adhesion failures caused by condensation. Moisture Clean-up Solvent: and Heat Loss - Every home contains moist air (water vapor) that, in Soap and water the proper proportion, provides a healthy atmosphere. But under winter conditions, when the inside/outside temperatures differ Finish: Flat drastically, the moisture indoors passes through interior walls and condenses within the stud space as it seeks the colder exterior side. Density: The moisture may fill the pockets or voids in insulation, increasing 10.5 lbs/gal (1.26 kg/L) the flow of heat, reducing its insulation value. Insulation must be dry Solids: to function efficiently. Keeping water vapor inside the home will help reduce heat loss and Volume - 34% +/- 1% Weight - 48% +/- 1% guard against moisture damage. Vapor barrier systems can help to provide this protection. Therefore, to help keep moisture inside VOC: apply 1060 Vapor Barrier Interior Primer Sealer to interior walls and 100 g/L (0.84 lbs/gal) maximum ceilings that contact the outside of any unheated areas. To be Refer to MSDS for regulatory VOC effective, a product must have a perm rating of less than 1.0, as set forth by the Federal Housing Administration Minimum Property content of complete product line Standards. -

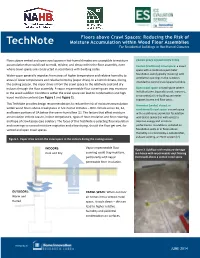

Floors Above Crawl Spaces: Reducing the Risk of Moisture Accumulation Within Wood Floor Assemblies 3 Building Code

Floors above Crawl Spaces: Reducing the Risk of TechNote Moisture Accumulation within Wood Floor Assemblies For Residential Buildings in Hot-Humid Climates Floors above vented and open crawl spaces in hot-humid climates are susceptible to moisture CRAWL SPACE FOUNDATION TYPES accumulation that could lead to mold, mildew, and decay within the floor assembly, even Vented (traditional) crawl space: a crawl where crawl spaces are constructed in accordance with building codes. space with a continuous perimeter Water vapor generally migrates from areas of higher temperature and relative humidity to foundation wall (typically masonry) with ventilation openings to the outdoors areas of lower temperature and relative humidity (vapor drive). In a humid climate, during intended to control crawl space humidity. the cooling season, the vapor drive is from the crawl space to the relatively cool and dry indoors through the floor assembly. A vapor impermeable floor covering can trap moisture Open crawl space: a crawl space where in the wood subfloor Conditions within the crawl space can lead to condensation and high individual piers (typically wood, masonry, or concrete) at the building perimeter wood moisture content (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). support beams and floor joists. This TechNote provides design recommendations to reduce the risk of moisture accumulation Unvented (sealed, closed, or within wood floors above crawlspaces in hot-humid climates – IECC climate zones 1A, 2A, conditioned) crawl space: a crawl space and lower portions of 3A below the warm-humid line [1]. The factors that affect moisture with a continuous perimeter foundation accumulation include season, indoor temperature, types of floor insulation and floor covering, wall that is sealed (no wall vents) to and type of crawl space (see sidebar). -

Preventing Moisture Accumulation in Ducts

INSULATION Glass Fiber Air Transmission Systems: FACTS # Preventing Moisture 52 Accumulation in Ducts In this issue we will address It doesn’t matter what the the sources of water accumu- duct is made of — bare sheet lation in unused ducts located metal, fiber glass lined sheet in unconditioned spaces; the metal, wrapped metal, duct problems associated with board, or flexible duct — the moisture accumulation; and physical laws governing this the means of prevention. phenomenon are the same for all materials. During the heating season, unused air conditioning ducts located in unconditioned spaces How Moisture can become saturated with Accumulates in Ducts water unless certain precautions Ducts without heated air flow- are taken. Low duct tempera- ing through them will cool to tures often result in condensa- temperatures near that of the tion which can accumulate in unconditioned space. substantial amounts of water Insulation, by itself, will not during the winter months. keep unused duct temperatures elevated or stable. Insulation will slow down Sources of Moisture the rate of heat flow through in the Home the duct wall, but unless this The source of accumulated heat is replaced, the tempera- water in unused or non-operat- ture in the duct will fall. When ing ducts is the air within a the temperature falls low home. All air contains some enough, the moisture laden air water in the form of water from within the home will vapor. However, in winter, inside begin to lose its moisture and air typically has more water form condensation. vapor than outside air. When Unless heat is supplied to water vapor laden air cools to a the inside of the duct, conden- low enough temperature, it con- sation will continue to form denses, forming liquid water. -

Vapor and Gas Barriers Critical Building Protection

PROVIDING A FULL BUILDING ENVELOPE SYSTEM VAPOR AND GAS BARRIERS CRITICAL BUILDING PROTECTION 13895-57277 Meadows-2021.indd 1 5/4/21 2:16 PM VAPOR RETARDANT STANDARDS The importance of a proven vapor and/or gas barrier. Uncontrolled water vapor through concrete slabs has cost building Underslab Vapor Barriers owners, designers and contractors billions of dollars. This moisture The use of underslab vapor barriers is the best method and infiltration into structures contributes to the proliferation of mold, most economical solution for controlling water vapor migration mildew and fungus that can lead to flooring system failures, through concrete slabs. The issue of admixtures and topically including adhesive failures, warping, blistering and staining. In applied materials does not address the issue that concrete cracks addition, water vapor migration carrying alkali can cause structural or the potential for elevated PH levels. failure of the concrete when reinforcing steel is present. ASTM E1993 and ASTM E1745 are the two industry standards Issues Directly Related to Flooring System Failures for vapor barriers and retarders under concrete slabs in contact • Many flooring systems used today form vapor barriers on top with soil. Note that typical polyethylene film does not meet the of concrete slabs and therefore trap water and alkali between requirements of these standards. the flooring system and the slab. Why Use a Gas Barrier? • 1999 federal mandate on VOC emissions created the need and In addition to the concern for moisture protection, other below- use of water-based flooring adhesives. grade contaminants have been identified as being major issues when it comes to occupant health and safety.