Indiana Archives African American History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythmandblues

RHYTHMANDBLUES Black PDs Examine Reasons TOP 7514LBUMS For Lack Of R&B Airplay Weeks Weeks by Carita Spencer On On 12/24 Chart 12/24 Chart LOS ANGELES - The reasons sur- trend towards mellower is a "cop out," 1 ALL IN ALL 37 NEW HORIZON rounding the issue of the difficutly black stating that songs like Dorothy Moore's EARTH, WIND & FIRE ISAAC HAYES (Polydor PD -1-6120) 44 6 R&B singles are experiencing in receiving "With Pen In Hand," "You Are My Friend," (Columbia JC 34905) 1 5 by Patti LaBelle and the 38 COCOMOTION airplay from Top 40 stations and the subse- Blackbyrds' "Soft 2 LIVE! EL COCO (AVI 6012) 35 12 quent decline in the number of R&B singles And Easy" are all examples of "soft pretty THE COMMODORES on the pop are music" which is conducive to the formats of (Motown M9 -894A2) 2 8 charts varied, depending on CHIC these stations. "There seems a (Atlantic SD 5202) 58 4 who is responding. A number of program to be stigma 3 REACH FOR IT directors and one music director affiliated attached to R&B music," he said. GEORGE DUKE (Epic JE 34883) 3 12 40 HEADS with Los Angeles area black radio stations "Everything that comes out R&B is not a BOB JAMES 4 IN FULL BLOOM (Columbia/Tappan Zee JC 34896) 33 7 were given the opportunity to voice their disco -boogie number. Young white kids ROSE ROYCE (Whitfield/WB WH3074) 4 20 opinions concerning this matter in an effort are dancing and are into R&B music more t1 THE BELLE ALBUM to shed a than ever before. -

Program Lists

Drum Tree - Program lists Kit Name Reference Artists Reference Songs Drummer GREATEST HITS 1 60’s Detroit Pop Gladys Knight & the Pips I Heard It Through the Grapevine Roger Hawkins 1966 2 UK Psychedelic Rock The Beatles Strawberry Fields Forever Ringo Starr 1967 3 King of Soul James Brown Sex Machine John "Jabo" Starks 1970 4 60's R&B Donny Hathaway What's Going On 1972 5 70's UK Hard Rock Led Zeppelin Black Dog John Bonham 1971 6 70's Funk Fusion Herbie Hancock Chameleon Harvey Mason 1973 7 King of Reggae Bob Marley I Shot the Sherrif Carlton Barrett 1973 8 70’s Detroit Pop Stevie Wonder Sir Duke Stevie Wonder 1976 9 70's Free Soul Deniece Williams Free Maurice White or Freddie White 1976 10 King of Pop Michael Jackson Rock With You John Robinson 1979 11 Grunge Rock Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit Dave Grohl 1991 12 Punk Rock Green Day Basket Case Tré Cool 1994 13 90's R&B Elisha La’verne Your Love Sends Me 1998 14 Neo Soul Erykah Badu Orange Moon Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson 2000 HISTORIC JAZZ 15 30’s Big Band Benny Goodman Sing Sing Sing Gene Krupa 1938 16 Be Bop “bird” Charlie Parker Bebop & Bird Max Roach 1947 17 50's Hard Bop Miles Davis Quintet Relaxin’ Philly Joe Jones 1957 18 “Blue”Jazz Art Blakey & the Jazz Free for All Art Blakey 1964 Messengers 19 60's Jazz 20 60's Free Jazz CONTEMPORARY JAZZ 21 NY Contemporary 22 Jazz Funk Maceo Parker Shake Everything You've Got Kenwood Dennard 1992 23 Modern Jazz 24 Dark & Dry Jack Dejohnette 25 Brooklyn Jazz Gretchen Parlato Weak Kendrick Scott 2009 26 Hiphop Jazz Other Snares 26 Piccolo SN 27 Piccolo-HH 28 Piccolo-Tamb 29 Piccolo-TambMute 30 Ludwig LM400 31 LM400-HH 32 LM400-Tamb 33 Yamaha 60s 34 Yamaha 60s HiPitch 35 Gretsch 60s Wood 36 BlackBeauty 20s Mute 37 BlackBeauty 20s 38 Slingerland 50s 39 Slingerland HiPitch 40 Heavy SN (Pearl Limp Bizkit Take a look around John Otto 2000 Sensitone Brass) 41 Tamb SN. -

I'm Missing You, Is a Soul Jerking, Emotional Song That Anyone Who

I’m Missing You, is a soul jerking, emotional song that anyone who has lost their mother or any loved one can relate to. From the pen, mind, and musical arrangement of drummer Fred Dinkins and the musical composition of Darryl Alston, Fred was able capture his true feelings into one song, and was able to channel the loss of his mother into this riveting masterpiece. Fred knew only one voice that would make his work complete, and that was his good friend, Deniece Williams. Deniece is known for having complete control over her four octave vocal range, in which she uses to channel the sound of angels in this song. Flowing from verse to chorus Deniece captures Fred’s message to his mother. Grammy Award Nominee, Author, and Los Angeles’ top rated instructor, Fred Dinkins has been known as the singer’s heart beat and pulse since he began performing in St. Louis Mo. as a Gospel Drummer. Fred performed with the likes of, The O’Neal Twins, Albertina Walker, and Vanessa Bell Armstrong. After moving to Los Angeles, Fred began studying at Musicians Institute, under likes of Joe Pocaro and Ralph Humphreys. As soon as Fred graduated, he quickly pursued his musical career, where he started performing with some of the Gospel greats such as Andre Crouch, and Tramaine Hawkins. Next, Fred began to explore different genres, such as Jazz and R&B, where he found himself performing with artists such as, Sam Riney, Hugh Masekela and Janice Marie and Taste of Honey to name a few. Fred became the Musical Director for The Emotions where he produced a live CD and performed on Good Morning America, Sinbad’s Funkfest Live In Aruba that aired on HBO. -

Dj Vladi Playlist Christmas Songs 2014

DJ VLADI PLAYLIST CHRISTMAS SONGS 2014 Dean Martin - Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Judith Durham - White Christmas Al Martino - Silver Bells Jo Stafford - Winter Wonderland Bing Crosby - Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas Vera Lynn - Away In A Manger Wayne Newton - Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Ella Fitzgerald - God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen John Farnham - The First Noel Anne Murray - It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Dion - Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree Crystal Gayle - I'll Be Home For Christmas Jan & Dean - Frosty The Snowman Les Paul - Jingle Bells The Spinners - The Twelve Days Of Christmas Lou Rawls - Merry Christmas, Baby Carnie & Wendy Wilson - Jingle Bell Rock Ferrante & Teicher - Sleigh Ride Stacie Orrico - O Come, All Ye Faithful Matt Monro - Mary's Boy Chi ld Eternal - Amazing Grace Kenny Rogers - When A Child Is Born Jamelia - Last Christmas Celtic Woman - O Holy Night Sin ad O'Connor - Silent Night Aled Jones - Walking In The Air Shirley Bassey - Ave Maria {Disc 2} Cliff Richard - Mistletoe And Wine Sarah Brightman - I Believe In Father Christmas the bird and the bee - Carol Of The Bells Amy Grant - Grown-Up Christmas List Glen Campbell - Blue Christmas Deniece Williams - Do You Hear What I Hear? Willie Nelson feat. Norah Jones - Baby It's Cold Outside Bobby Goldsboro - Look Around You Andy Williams - Christmas Holiday Barry Blue - Christmas Moon 11.Keith Marshall - Another Christmas Aaron Neville - Christmas Prayer Dianne Reeves - Christmas Time Is Here Bebe & Cece Winans - Joy To The World Faith Evans -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. MSR SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Hello Rolling in the Deep Someone Like You Alicia Keys Underdog Andra Day Rise Up Ariana Grande 7 Rings Breathin Problems Thank You Next Beyonce Crazy in Love Halo Love on Top Single Ladies The Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Blink 182 All the Small Things Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Just the Way You Are Locked Out of Heaven That's What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B I Like It Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Camila Cabello Havana Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don’t Let Me Down Chris Brown Look at Me Now Clean Bandit Rather Be Echosmith Cool Kids Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake God’s Plan Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Toosie Slide Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Ginuwine Pony Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gotye Somebody That I Used to Know Halsey Without Me Icona Pop I Love It Iggy Azalea Fancy Imagine Dragons Radioactive Jason Derulo Talk Dirty to Me The Other Side Want -

EARTH, WIND & FIRE -‐ Bio XRIJF JUNE 20-‐28, 2014 During the 1970S

EARTH, WIND & FIRE - Bio During the 1970s, a new brand of pop music was born - one that was steeped in African and African- American styles - particularly jazz and R&B but appealed to a broader cross-section of the listening public. As founder and leader of the band Earth, Wind & Fire, Maurice White not only embraced but also helped bring about this evolution of pop, which bridged the gap that has often separated the musical tastes of black and white America. It certainly was successful, as EWF combined high-caliber musicianship, wide-ranging musical genre eclecticism, and '70s multicultural spiritualism. "I wanted to do something that hadn't been done before," Maurice explains. "Although we were basically jazz musicians, we played soul, funk, gospel, blues, jazz, rock and dance music...which somehow ended up becoming pop. We were coming out of a decade of experimentation, mind expansion and cosmic awareness. I wanted our music to convey messages of universal love and harmony without force- feeding listeners' spiritual content." Maurice was born December 19, 1941, in Memphis, TN. He was immersed in a rich musical culture that spanned the boundaries between jazz, gospel, R&B, blues and early rock. All of these styles played a role in the development of Maurice's musical identity. At age six, he began singing in his church's gospel choir but soon his interest turned to percussion. He began working gigs as a drummer while still in high school. His first professional performance was with Booker T. Jones, who eventually achieved stardom as Booker T and the MGs. -

Top of the Pops 18/04/68

TOP OF THE POPS 18/04/68 TOP OF THE POPS 13/06/68 Introduced by Alan Freeman & Stuart Henry Introduced by Pete Murray Englebert Humperdinck - A Man Without Love (Studio) Des O’Connor - I Pretend (Studio) (rpt) John Rowles - If I Only Had Time (Studio) Don Partridge - Blue Eyes (Studio) (rpt) Reparata & The Delrons - Captain Of Your Ship (Studio) (rpt) Donovan - Hurdy Gurdy Man (Studio) Spanky & Our Gang - Like To Get To Know You (Studio) Esther & Abi Ofarim - One More Dance (Studio) Box Tops - Cry Like A Baby (Disc/Dancers) John Rowles - Hush Not A Word To Mary (Studio) Kinks - Wonderboy (Studio) Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger & The Trinity - This Wheel’s On Fire (Studio) (rpt) Paper Dolls - Something Here In My Heart (Studio) Marmalade - Lovin’ Things (Studio) Showstoppers - Ain’t Nothing But A Houseparty (Studio) Gary Puckett & The Union Gap - Young Girl (Promo) Louis Armstrong - What A Wonderful World (Promo) TOP OF THE POPS 20/06/68 TOP OF THE POPS 25/04/68 Introduced by Stuart Henry Introduced by Jimmy Savile Cliff Richard - I’ll Love You Forever Today (Studio) 1910 Fruitgum Co - Simon Says (Disc) Des O’Connor - I Pretend (Studio) (rpt) Honeybus - I Can’t Let Maggie Go (Studio) (rpt) Don Partridge - Blue Eyes (Studio) (rpt) Jacky - White Horses (Studio) Lulu - Boy (Studio) (rpt) Sandie Shaw - Don’t Run Away (Studio) Marmalade - Lovin’ Things (Studio) Scott Walker - Joanna (Studio) Equals - Baby Come Back (Studio) Herd - I Don’t Want Our Loving To Die (Studio) (rpt) Rolling Stones - Jumping Jack Flash (Disc/Dancers) Hollies - Jennifer -

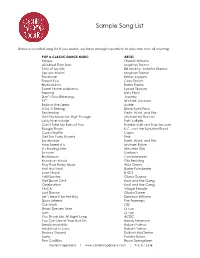

Sample Song List

Sample Song List Below is a partial song list. If you prefer, we have enough repertoire to play one style all evening. POP & CLASSIC DANCE MUSIC ARTIST Happy Pharrell Williams All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Time of My Life Bill Medley, Jennifer Warner Lips Are Movin’ Meghan Trainor Footloose Kenny Loggins Forget You Celo Green Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Sweet Home Alabama Lynyrd Skynyrd Firework Katy Perry Don’t Stop Believing Journey PYT Michael Jackson Rollin in the Deep Adele I Got A Feeling Black Eyed Peas September Earth, Wind, and Fire Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald Lady Marmalade Patti LaBelle Can’t Take My Eyes of You Frankie Valli and Four Seasons Boogie Shoes K.C. and the Sunshine Band Cupid Shuffle Cupid Get This Party Started Pink September Earth, Wind, and Fire How Sweet it Is Michael Buble It’s Raining Men Weather Girls Smooth Santana Brickhouse Commordores Knock on Wood Otis Redding Play That Funky Music Wild Cherry Hot! Hot! Hot! Buster Poindexter Love Shack B 52’S I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Get Down On It Kool and the Gang Celebration Kool and the Gang YMCA Village People Last Dance Gloria Gainer Let’s Hear It for the Boy Deniece Williams Disco Inferno The Trammps Car Wash LTD Sharp Dressed Man ZZ Top Tush ZZ Top You Shook Me All Night Long ACDC You Can Leave Your Hat On Randy Newman Simply Irresistible Robert Palmer Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Shakey Ground Delbert McClinton Jump Pointer Sisters Pink Cadillac Bruce Springsteen Center Stage Band l www.centerstageband.com l 972.317.2336 POP & CLASSIC-BALLADS -

REMEMBERING the MAN in the MIRROR By: David Walker Reactions from Fans Were Posted Across Little Michael on TV During the Jackson Ways Beyond Belief

ENTERTAINMENT 8 THE COMPASS - FALL 2009 REMEMBERING THE MAN IN THE MIRROR By: David Walker reactions from fans were posted across little Michael on TV during the Jackson ways beyond belief. Jackson contributed Michael Jackson, the King of Pop, their website. 5 era. Children can also be spotted with and gave back to the world more than the “Thriller fever”. was rushed to U.C.L.A. Medical Center Black Entertainment Television paid music; he gave back a spirit that will on June 25, 2009. Hours later the forever be remembered. The pop homage to the King of Pop and the With the fame and stardom comes the announcement of the world-renowned Jackson family during its annual Black price many must pay with it. culture has lost a pioneer but his lasting music icon death brought the world to affect on the world will last forever. Entertainment Television Award. Controversy surrounded Jackson a halt. Michael’s father, Joe Jackson, and throughout his lifetime. This included Jackson’s sudden death shocked his sister Janet Jackson were present at the the times of his father’s alleged millions of fans that Thursday. Often awards. Janet was the spokesperson for excessive abuse, demanding the best of imitated but always original, Jackson’s the entire family his children, and what some say was the style left a moon-walking footprints on The youngest of the Jackson worst that he did to his talented son, the music industry and society. daughters reminded the BET audience destroying his image of himself which Just before he could give the world that the Jackson family was hurting just most agree lead him to embark upon t'; another com eback the shocking 911 call like many o f them , and she thanked BET a number of plastic surgeries to create .• was dialed from the Jackson mansion. -

Jukebox Oldies

JUKEBOX OLDIES – MOTOWN ANTHEMS Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Baby Love The Supremes 01 I Heard It Through the Grapevine Marvin Gaye 02 Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 02 Jimmy Mack Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 03 Reach Out, I’ll Be There Four Tops 03 You Keep Me Hangin’ On The Supremes 04 Uptight (Everything’s Alright) Stevie Wonder 04 The Onion Song Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 05 Do You Love Me The Contours 05 Got To Be There Michael Jackson 06 Please Mr Postman The Marvelettes 06 What Becomes Of The Jimmy Ruffin 07 You Really Got A Hold On Me The Miracles 07 Reach Out And Touch Diana Ross 08 My Girl The Temptations 08 You’re All I Need To Get By Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 09 Where Did Our Love Go The Supremes 09 Reflections Diana Ross & The Supremes 10 I Can’t Help Myself Four Tops 10 My Cherie Amour Stevie Wonder 11 The Tracks Of My Tears Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 11 There’s A Ghost In My House R. Dean Taylor 12 My Guy Mary Wells 12 Too Busy Thinking About My Marvin Gaye 13 (Love Is Like A) Heatwave Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 13 The Happening The Supremes 14 Needle In A Haystack The Velvelettes 14 It’s A Shame The Spinners 15 It’s The Same Old Song Four Tops 15 Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross 16 Get Ready The Temptations 16 Ben Michael Jackson 17 Stop! (in the name of love) The Supremes 17 Someday We’ll Be Together Diana Ross & The Supremes 18 How Sweet It Is Marvin Gaye 18 Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations 19 Take Me In Your Arms Kim Weston 19 I’m Still Waiting Diana Ross 20 Nowhere To Run Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 20 I’ll Be There The Jackson 5 21 Shotgun Junior Walker & The All Stars 21 What’s Going On Marvin Gaye 22 It Takes Two Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston 22 For Once In My Life Stevie Wonder 23 This Old Heart Of Mine The Isley Brothers 23 Stoned Love The Supremes 24 You Can’t Hurry Love The Supremes 24 ABC The Jackson 5 25 (I’m a) Road Runner JR. -

~Tatc of '1:Ccnnc.S.Scc

~tatc of '1:Ccnnc.s.scc HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION NO. 574 By Representatives Miller, Camper, Turner, Akbari, Todd, Coley, Lollar, Hardaway, DeBerry, Armstrong, Towns, Parkinson, Cooper, McManus, Mark White, Alexander, Beck, Harry Brooks, Kevin Brooks, Byrd, Calfee, Carr, Carter, Casada, Clemmons, Daniel, Doss, Dunlap, Dunn, Durham, Eldridge, Faison, Farmer, Favors, Fitzhugh, Forgety, Gilmore, Goins, Gravitt, Halford, Hawk, Hazlewood, Hicks, Matthew Hill, Timothy Hill, Holsclaw, Howell, Hulsey, Jenkins, Jernigan, Johnson, Kane, Keisling, Kumar, Lamberth, Littleton, Love, Lundberg, Lynn, Marsh, Matheny, Matlock, McCormick, McDaniel, Mitchell, Moody, Pitts, Powell, Powers, Reedy, Rogers, Sanderson, Sargent, Cameron Sexton, Jerry Sexton, Shepard, Smith, Stewart, Swann, Terry, Travis, Van Huss, Weaver, Dawn White, Williams, Windle, Wirgau, Zachary, and Madam Speaker Harwell A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of Maurice White. WHEREAS, the members of this General Assembly were greatly saddened to learn of the passing of Maurice White, an innovative and multitalented musician, singer, songwriter, record producer, arranger, and founder and leader of Earth, Wind & Fire (EW&F), one of the most popular and enduring musical groups of all time; and WHEREAS, during the course of a long and distinguished career, Mr. White won seven Gram mys and was nominated for twenty-one Gram mys in total; and WHEREAS, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Vocal Group Hall of Fame as a member of EW&F and individually inducted into the Songwriters -

David L. Smith Collection Ca

Collection # P 0568 OM 0616 CT 2355–2368 DVD 0866–0868 DAVID L. SMITH COLLECTION CA. 1902–2014 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Processed by Barbara Quigley and Courtney Rookard February 27, 2017 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 6 boxes of photographs, 1 OVA graphics box, 1 OVB COLLECTION: photographs box, 4 flat-file folders of movie posters; 1 folder of negatives; 9 manuscript boxes; 7 oversize manuscript folders; 1 artifact; 14 cassette tapes; 3 CDs; 1 thumb drive; 18 books COLLECTION 1902–2014 DATES: PROVENANCE: Gift from David L. Smith, July 2015 RESTRICTIONS: Any materials listed as being in Cold Storage must be requested at least 4 hours in advance. COPYRIGHT: The Indiana Historical Society does not hold the copyright for the majority of the items in this collection. REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2015.0215, 2017.0023 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH David L. Smith is Professor Emeritus of Telecommunications at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, where he taught for twenty-three years. He is the author of Hoosiers in Hollywood (published by the Indiana Historical Society in 2006), Sitting Pretty: The Life and Times of Clifton Webb (University Press of Mississippi, 2011), and Indianapolis Television (Arcadia Publishing, 2012). He was the host of a series called When Movies Were Movies on WISH-TV in Indianapolis from 1971–1981, and served as program manager for the station for twenty years.