World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 Pertamina Annual Report.Pdf

Perjalanan menuju Kesempurnaan Road to Excellence Usaha yang dijalani tak hanya untuk kita sendiri, These efforts are not merely for us Hasil yang diraih tak membuat kita menjadi pamrih, Things we've attained we've done it unconditionally Prestasi tertinggi tak akan membuat kita berhenti… No achievement is high enough Karena kita akan selalu menjadi, For we always, Yang menyokong keberhasilan negeri ini Will be there for the success of this country. 01 Perjalanan menuju Kesempurnaan Laporan Tahunan PERTAMINA 2008 | Annual Report 02 Perjalanan menuju Kesempurnaan Laporan Tahunan PERTAMINA 2008 | Annual Report SEKILAS PERTAMINA PERTAMINA IN BRIEF 03 Perjalanan menuju Kesempurnaan Laporan Tahunan PERTAMINA 2008 | Annual Report PERTAMINA IN BRIEF HULU / UPSTREAM HILIR / DOWNSTREAM PEMASARAN / MARKETING 04 Perjalanan menuju Kesempurnaan Laporan Tahunan PERTAMINA 2008 | Annual Report PERTAMINA IN BRIEF KOMITMEN PERUSAHAAN CORPORATE COMMITMENTS VISI VISION Menjadi Perusahaan Minyak Nasional Kelas To become a World Class National Oil Company. Dunia. MISI MISSION Menjalankan usaha inti minyak, gas dan Integratedly performing core business of oil, gas, bahan bakar nabati secara terintegrasi, and biofuel, based on strong commercial berdasarkan prinsip-prinsip komersial yang principles. kuat. 05 Perjalanan menuju Kesempurnaan Laporan Tahunan PERTAMINA 2008 | Annual Report PERTAMINA IN BRIEF TATA NILAI VALUES Clean (Bersih) Clean Dikelola secara professional, menghindari benturan Professionally managed, avoiding conflict of interest, intolerate kepentingan, -

Naskah Publikasi Teknik Sipil

STUDI POTENSI PENUMPANG DAN RUTE PADA RENCANA PEMBANGUNAN MONOREL DI KOTA MALANG NASKAH PUBLIKASI TEKNIK SIPIL Ditujukan untuk memenuhi persyaratan memperoleh gelar Sarjana Teknik MUHAMMAD IQBAL ZUHDI NIM. 145060101111026 ROBBY FREDYANTO NIM. 145060101111007 UNIVERSITAS BRAWIJAYA FAKULTAS TEKNIK MALANG 2018 STUDI POTENSI PENUMPANG DAN RUTE PADA RENCANA PEMBANGUNAN MONOREL DI KOTA MALANG (Potential Analysis of Passenger and Route on Monorail Construction Planning in Malang City) Muhammad Iqbal Zuhdi, Robby Fredyanto, Ludfi Djakfar dan Rahayu Kusumaningrum Jurusan Teknik Sipil Fakutas Teknik Universitas Brawijaya Jalan M.T. Haryono 167, Malang 65145, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRAK Kota Malang adalah kota terbesar kedua di provinsi Jawa Timur, Indonesia, dengan jumlah penduduk mencapai 908.395 jiwa. Kemacetan merupakan permasalahan yang tidak dapat dihindari di Kota Malang. Masalah tersebut menyebabkan masyarakat mencari alternatif moda transportasi lain yang berkualitas, aman, nyaman dan efisien, yaitu berupa Sistem Angkutan Umum Massal (SAUM). Untuk menciptakan Sistem Angkutan Umum Massal (SAUM) yang berkualitas maka akan dibangun Monorel di Kota Malang. Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui karakteristik umum dan karakteristik perjalanan pengguna kendaraan pribadi (mobil dan sepeda motor) di Kota Malang saat ini, untuk mengetahui rute potensial moda transportasi Monorel di Kota Malang, dan untuk mengetahui potensi penumpang pada moda transportasi Monorel di Kota Malang. Pada penelitian ini dilakukan pengumpulan data primer berupa karakteristik umum, karakteristik perjalanan, pemilihan moda, dan rute Monorel dengan menggunakan kuesioner Stated Preference dan wawancara kepada responden. Jumlah kebutuhan sampel pada penelitian ini dihitung dengan rumus Slovin dan didapatkan jumlah kebutuhan sampel sebanyak 400 responden pengguna kendaraan pribadi. Survei dilakukan pada pusat keramaian di Kota Malang pada hari kerja dan akhir pekan, yaitu disekitar Jl. -

Analisis Kepuasan Penumpang Terhadap Kinerja Pelayanan Dan Intermoda Di Stasiun Kereta Api Madiun

TESIS ANALISIS KEPUASAN PENUMPANG TERHADAP KINERJA PELAYANAN DAN INTERMODA DI STASIUN KERETA API MADIUN ARINDA LELIANA 03111650060005 DOSEN PEMBIMBING: Ir. Hera Widyastuti, M.T., Ph.D. PRORAM MAGISTER BIDANG KEAHLIAN MANAJEMEN DAN REKAYASA TRANSPORTASI DEPARTEMEN TEKNIK SIPIL FAKULTAS TEKNIK SIPIL LINGKUNGAN DAN KEBUMIAN INSTITUT TEKNOLOGI SEPULUH NOPEMBER SURABAYA 2018 THESIS ANALYSIS PASSENGER SATISFACTION FOR SERVICE PERFORMANCE AND INTERMODAL AT THE RAILWAYS STATION MADIUN ARINDA LELIANA 03111650060005 SUPERVISOR : Ir. Hera Widyastuti, M.T., Ph.D. MASTER PROGRAM MANAGEMENT AND TRANSPORTATION ENGINEERING CIVIL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CIVIL ENGINEERING ENVIRONMENT AND GEOSCIENCE SEPULUH NOPEMBER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SURABAYA 2018 ii iii Halaman Sengaja Dikosongkan iv ANALISIS KEPUASAN PENUMPANG TERHADAP KINERJA PELAYANAN DAN INTERMODA DI STASIUN KERETA API MADIUN Nama mahasiswa : Arinda Leliana NRP : 03111650060005 Pembimbing : Ir. Hera Widyastuti, M.T., Ph.D. ABSTRAK Tingginya minat masyarakat yang naik kereta api maka pemerintah berupaya meningkatkan kapasitas kereta api. Rel jalur tunggal saat ini sudah tidak seimbang seiring dengan banyaknya jumlah frekuensi kereta api yang menggunakannya. Salah satu upaya pemberian pelayanan yang lebih baik kepada penumpang yaitu dilakukan perbaikan jalur ganda. Sebanding dengan hal itu perlu peningkatan prasarana penyedia jasa kereta api yaitu stasiun. Stasiun harus mampu menampung kebutuhan pengguna jasa dalam memberikan pelayanan dan fasilitas terbaik pada penumpang. Mayoritas penumpang -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 For

Aliran Monthly : Vol.31(3) Page 1 For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2011(026665) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 COVER STORY Making sense of the forthcoming Sarawak state elections Will electoral dynamics in the polls sway to the advantage of the opposition or the BN? by Faisal S. Hazis n the run-up to the 10th all 15 Chinese-majority seats, spirit of their supporters. As III Sarawak state elections, which are being touted to swing contending parties in the com- II many political analysts to the opposition. Pakatan Rakyat ing elections, both sides will not have predicted that the (PR) leaders, on the other hand, want to enter the fray with the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) will believe that they can topple the BN mentality of a loser. So this secure a two-third majority win government by winning more brings us to the prediction made (47 seats). It is likely that the coa- than 40 seats despite the opposi- by political analysts who are ei- lition is set to lose more seats com- tion parties’ overlapping seat ther trained political scientists pared to 2006. The BN and claims. Which one will be the or self-proclaimed political ob- Pakatan Rakyat (PR) leaders, on likely outcome of the forthcoming servers. Observations made by the other hand, have given two Sarawak elections? these analysts seem to represent contrasting forecasts which of the general sentiment on the course depict their respective po- Psy-war versus facts ground but they fail to take into litical bias. Sarawak United consideration the electoral dy- People’s Party (SUPP) president Obviously leaders from both po- namics of the impending elec- Dr George Chan believes that the litical divides have been engag- tions. -

2016 N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) / State Constituencies

SARAWAK - 2016 N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) / State Constituencies KAWASAN / STATE PENYANDANG / INCUMBENT PARTI / PARTY N1 OPAR RANUM ANAK MINA BN-SUPP N2 TASIK BIRU DATO HENRY @ HARRY AK JINEP BN-SPDP N3 TANJUNG DATU ADENAN BIN SATEM BN-PBB N4 PANTAI DAMAI ABDUL RAHMAN BIN JUNAIDI BN-PBB N5 DEMAK LAUT HAZLAND BIN ABG HIPNI BN-PBB N6 TUPONG FAZZRUDIN ABDUL RAHMAN BN-PBB N7 SAMARIANG SHARIFAH HASIDAH BT SAYEED AMAN GHAZALI BN-PBB N8 SATOK ABG ABD RAHMAN ZOHARI BIN ABG OPENG BN-PBB N9 PADUNGAN WONG KING WEI DAP N10 PENDING VIOLET YONG WUI WUI DAP N11 BATU LINTANG SEE CHEE HOW PKR N12 KOTA SENTOSA CHONG CHIENG JEN DAP N13 BATU KITANG LO KHERE CHIANG BN-SUPP N14 BATU KAWAH DATUK DR SIM KUI HIAN BN-SUPP N15 ASAJAYA ABD. KARIM RAHMAN HAMZAH BN-PBB N16 MUARA TUANG DATUK IDRIS BUANG BN-PBB N17 STAKAN DATUK SERI MOHAMAD ALI MAHMUD BN-PBB N18 SEREMBU MIRO AK SIMUH BN N19 MAMBONG DATUK DR JERIP AK SUSIL BN-SUPP N20 TARAT ROLAND SAGEH WEE INN BN-PBB N21 TEBEDU DATUK SERI MICHAEL MANYIN AK JAWONG BN-PBB N22 KEDUP MACLAINE BEN @ MARTIN BEN BN-PBB N23 BUKIT SEMUJA JOHN AK ILUS BN-PBB N24 SADONG JAYA AIDEL BIN LARIWOO BN-PBB N25 SIMUNJAN AWLA BIN DRIS BN-PBB N26 GEDONG MOHD.NARODEN BIN MAJAIS BN-PBB N27 SEBUYAU JULAIHI BIN NARAWI BN-PBB N28 LINGGA SIMOI BINTI PERI BN-PBB N29 BETING MARO RAZAILI BIN HAJI GAPOR BN-PBB N30 BALAI RINGIN SNOWDAN LAWAN BN-PRS N31 BUKIT BEGUNAN DATUK MONG AK DAGANG BN-PRS N32 SIMANGGANG DATUK FRANCIS HARDEN AK HOLLIS BN-SUPP N33 ENGKILILI DR JOHNICAL RAYONG AK NGIPA BN-SUPP N34 BATANG AI MALCOM MUSSEN ANAK LAMOH BN-PRS N35 -

Adenan Hits Campaign Trail Running, Najib Goes to Hinterland Malaysiakini.Com Apr 29 Th , 2016 Adrian Wong and Lu Wei Hoong

Adenan hits campaign trail running, Najib goes to hinterland MalaysiaKini.com Apr 29 th , 2016 Adrian Wong and Lu Wei Hoong S'WAK POLLS As much as scandal-ridden Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak wants to secure BN victory in Sarawak, he is rarely seen campaigning in urban constituencies where the voters are more familiar with political development. This is the total opposite of the campaign trail of Sarawak BN chairperson Adenan Satem, a popular figure and super campaigner who has been making his rounds at all these constituencies. Riding on the ‘Adenan factor’, the caretaker chief minister has been going all out fishing for votes for BN candidates and BN direct candidates. Meanwhile, Najib, who has visited the Borneo state more than 50 times since he assumed premiership, mainly focused on bumiputera-majority and rural constituencies. His itinerary avoided urban seats, particularly Chinese-majority constituencies. The opposition has been maximising on the goods and services tax (GST) and Najib's scandals as campaign fodder, as these issues are being discussed by voters in the urban areas. In his attempt to capture a major vote bank, Adenan attended events organised by the big-six timber companies in the state before nomination day. At one event, he even reportedly warned the employees to choose between their rice bowl or vote for the opposition. 'Super weekend' trail Adenan, who appeared in the southern part of Sarawak after nomination day, is planning to spend the next two days – also called ‘super weekend’ – campaigning in the central and northern regions where SUPP had suffered huge losses to the opposition in previous elections. -

Laporan Keputusan Akhir Dewan Undangan Negeri Bagi Negeri Sarawak Tahun 2016

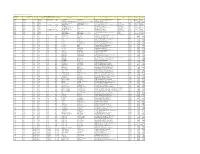

LAPORAN KEPUTUSAN AKHIR DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI SARAWAK TAHUN 2016 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.192-MAS GADING N.01 - OPAR RANUM ANAK MINA BN 3,665 MNG NIPONI ANAK UNDEK BEBAS 1,583 PATRICK ANEK UREN PBDSB 524 HD FRANCIS TERON KADAP ANAK NOYET PKR 1,549 JUMLAH PEMILIH : 9,714 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 57 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 7,419 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 41 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 76.40% MAJORITI : 2,082 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.192-MAS GADING N.02 - TASIK BIRU MORDI ANAK BIMOL DAP 5,634 HENRY @ HARRY ANAK JINEP BN 6,922 MNG JUMLAH PEMILIH : 17,041 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 197 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 12,797 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 44 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 75.10% MAJORITI : 1,288 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.03 - TANJONG DATU ADENAN BIN SATEM BN 6,360 MNG JAZOLKIPLI BIN NUMAN PKR 468 HD JUMLAH PEMILIH : 9,899 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 77 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 6,936 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 31 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 70.10% MAJORITI : 5,892 PRU DUN Sarawak Ke-11 1 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.04 - PANTAI DAMAI ABDUL RAHMAN BIN JUNAIDI BN 10,918 MNG ZAINAL ABIDIN BIN YET PAS 1,658 JUMLAH PEMILIH : 18,409 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 221 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 12,851 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 54 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 69.80% MAJORITI : 9,260 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.05 - DEMAK LAUT HAZLAND -

World Bank Document

AS132 This report was prepared for use within the Bank and its affiliated organizations. Public Disclosure Authorized They do not accept responsibility for its accuracy or completeness. The report may not be published nor may it be quoted as representing their views. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF INDONESIA (in six volumes) VOLUME IV ANNEX 2 - INDUSTRY Public Disclosure Authorized O ,--* February 12, 1968 0 o 0 0 Public Disclosure Authorized Asia Department n CD CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit - Rupiah Floating Rate (November 1967) (1) B. E. Market Rate U.S.$ 1. 00 = Rp. 150 1 Rupiah = U. S. $ 0. 007 1 Million Rupiahs = U. S. $ 6, 667 (2) Curb Rate U.S.$ 1. 00 = Rp. 170 1 Rupiah = U.S.$ 0.006 1 Million Rupiahs = U. S. $ 5, 882 This report was prepared by a mission that visited Indonesia from October 17 to November 15, 1967. The members of the mission were: 0. J. McDiarmid Chief of Mission B. K. Abadian Chief Economist Jack Beach Power N. D. Ganjei Fiscal (I.M.F.) D. Juel Planning G. W. Naylor Industry (Consultant) G. J. Novak National accounts J. Parmar Industry R. E. Rowe Agriculture M. Schrenk Industry H. van Helden Transportation E. Levy (part time) Statistics Mrs. N. S. Gatbonton (part time) External Debt Miss G. M. Prefontaine Secretary Messrs. R. Hablutzel and W. Ladejinsky also contributed to this report. Since the mission's visit substantial changes have occurred in the effective exchange rate structure and prices have risen at a more rapid rate than during the previous months of 1967. -

American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/ Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 Gouda, Frances; Brocades Zaalberg, Thijs

www.ssoar.info American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/ Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 Gouda, Frances; Brocades Zaalberg, Thijs Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Gouda, F., & Brocades Zaalberg, T. (2002). American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949. (American Studies). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn- resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-337325 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de FRANCES GOUDA with THIJS BROCADES ZAALBERG AMERICAN VISIONS of the NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES/INDONESIA US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS de 3e PROEF - BOEK 29-11-2001 23:41 Pagina 1 AMERICAN VISIONS OF THE NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES/INDONESIA de 3e PROEF - BOEK 29-11-2001 23:41 Pagina 2 de 3e PROEF - BOEK 29-11-2001 23:41 Pagina 3 AmericanVisions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia -

© 2016 Published by Center for Pulp and Paper Through 2Nd Reptech

Proceedings of 2nd REPTech Crowne Plaza Hotel, Bandung, November 15-17, 2016 ISBN : 978-602-17761-4-8 © 2016 Published by Center for Pulp and Paper through 2nd REPTech i Proceedings of 2nd REPTech Crowne Plaza Hotel, Bandung, November 15-17, 2016 ISBN : 978-602-17761-4-8 Proceedings International Symposium on 2nd Resource Efficiency in Pulp and Paper Technology Crowne Plaza Hotel, Bandung, November 15-17, 2016 EDITORIAL BOARD Hiroshi Ohi, University of Tsukuba, Japan Tanaka Ryohei, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Japan Kunio Yoshikawa, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan Hongbin Liu, Tianjin University of Science & Technology, China Hongjie Zhang, Tianjin University of Science & Technology, Tianjin, China Zuming Lv, China Cleaner Production Center of Light Industry, China Rusli Daik, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia Leh Cheu Peng, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Rushdan bin Ibrahim, Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Malaysia Herri Susanto, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia Subyakto, Research Center for Biomaterials-Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Indonesia Gustan Pari, Forest Product Research and Development Center, Indonesia Farah Fahma, Bogor Agricultural University, Indonesia Eko Bhakti Hardiyanto, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia Agus Purwanto, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia Subash Maheswari, PT. Tanjungenim Lestari Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Sari Farah Dina, Center for Research and Standardization Industry Medan, Indonesia Yusup Setiawan, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Lies Indriati, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Krisna Septiningrum, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Andri Taufick Rizaluddin, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Evi Oktavia, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Hendro Risdianto, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia Syamsudin, Center for Pulp and Paper, Indonesia --------- Cover Design by Nadia Ristanti Layout by Wachyudin Aziz CENTER FOR PULP AND PAPER MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY - REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA Jalan Raya Dayeuhkolot No. -

Winds of Change in Sarawak Politics?

The RSIS Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. If you have any comments, please send them to the following email address: [email protected]. Unsubscribing If you no longer want to receive RSIS Working Papers, please click on “Unsubscribe.” to be removed from the list. No. 224 Winds of Change in Sarawak Politics? Faisal S Hazis S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 24 March 2011 About RSIS The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. RSIS’ mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia-Pacific. To accomplish this mission, RSIS will: Provide a rigorous professional graduate education in international affairs with a strong practical and area emphasis Conduct policy-relevant research in national security, defence and strategic studies, diplomacy and international relations Collaborate with like-minded schools of international affairs to form a global network of excellence Graduate Training in International Affairs RSIS offers an exacting graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The teaching programme consists of the Master of Science (MSc) degrees in Strategic Studies, International Relations, International Political Economy and Asian Studies as well as The Nanyang MBA (International Studies) offered jointly with the Nanyang Business School. The graduate teaching is distinguished by their focus on the Asia-Pacific region, the professional practice of international affairs and the cultivation of academic depth.