The Intermediate Or Disembodied State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMI Films the Original Text Directly from the Copy Submitted

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ■A ccessing U the World's M Information since I 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Order Number 8827903 Breaking down the neurotic-psychotic artifice: The subversive function of myth in Goethe, Nietzsche, Rilke and Walter Benjam in Lundgren, Neale Powell, Ph.D. -

Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Vol. 05

Sermon #225 The New Park Street Pulpit 1 SATAN’S BANQUET NO. 225 A SERMON DELIVERED On SABBATH MORNING, NOVEMBER 28, 1858, BY THE REV. C. H. SPURGEON, AT THE MUSIC HALL, ROYAL SURREY GARDENS. “The governor of the feast called the bridegroom, and said unto him, every man at the beginning does set forth good wine; and when men have well drunk, then that which is worse: but you have kept the good wine until now.” John 2:9, 10. THE governor of the feast said more than he intended to say, or ra- ther, there is more truth in what he said than he himself imagined! This is the established rule all the world over—“The good wine first and when men have well drunk, then that which is worse.” It is the rule with men and have not hundreds of disappointed hearts bewailed it? Friendship first—the oily tongue, the words softer than butter and afterwards the drawn sword! Ahithophel first presents the lordly dish of love and kind- ness to David; then afterwards that which is worse, for he forsakes his master and becomes the counselor of his rebel son. Judas presents first of all the dish of fair speech and of kindness; the Savior partook thereof, he walked to the house of God in company with Him and took sweet counsel with Him. But afterwards, there came the dregs of the wine—“He that eats bread with Me has lifted up his heel against Me.” Judas, the thief, betrayed his Master, bringing forth afterwards “that which is worse.” You have found it so with many whom you thought your friends. -

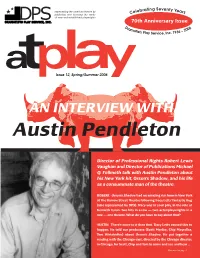

At Play Spring-Summer 06.Indd

rating Seventy Y representing the american theatre by eleb ears publishing and licensing the works C of new and established playwrights 70th Anniversary Issue D ram 06 ati – 20 sts Play Service, Inc. 1936 Issue 12, Spring/Summer 2006 AN INTERVIEW WITH Austin Pendleton Director of Professional Rights Robert Lewis Vaughan and Director of Publications Michael Q. Fellmeth talk with Austin Pendleton about his New York hit, Orson’s Shadow, and his life as a consummate man of the theatre. ROBERT. Orson’s Shadow had an amazing run here in New York at The Barrow Street Theatre following Tracy Letts’ fantastic Bug (also represented by DPS). Tracy was in your play, in the role of Kenneth Tynan. Two hits in a row — two actor/playwrights in a row — one theatre. What do you have to say about that? AUSTIN. There’s more to it than that. Tracy Letts caused this to happen. He told our producers (Scott Morfee, Chip Meyrelles, Tom Wirtshafter) about Orson’s Shadow. He put together a reading with the Chicago cast, directed by the Chicago director, in Chicago, for Scott, Chip and Tom to come and see and hear … Continued on page 3 NEWPLAYS Serving the American Theatre Since 1936: A Brief History of Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Rob Ackerman DISCONNECT. Goaded by the women they love “The Dramatists Play Service came into being at exactly the right moment and haunted by memories they can no longer for the contemporary playwright and the American theatre at large.” suppress, two men at a dinner party confront the —Audrey Wood, renowned agent to Tennessee Williams lies of their lives. -

BOOK of ENOCH From-The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament R.H

BOOK OF ENOCH From-The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament R.H. Charles Oxford: The Clarendon Press Section I. Chapters I-XXXVI INTRODUCTION [Chapter 1] 1 The words of the blessing of Enoch, wherewith he blessed the elect and righteous, who will be 2 living in the day of tribulation, when all the wicked and godless are to be removed. And he took up his parable and said -Enoch a righteous man, whose eyes were opened by God, saw the vision of the Holy One in the heavens, which the angels showed me, and from them I heard everything, and from them I understood as I saw, but not for this generation, but for a remote one which is 3 for to come. Concerning the elect I said, and took up my parable concerning them: The Holy Great One will come forth from His dwelling, 4 And the eternal God will tread upon the earth, (even) on Mount Sinai, [And appear from His camp] And appear in the strength of His might from the heaven of heavens. 5 And all shall be smitten with fear And the Watchers shall quake, And great fear and trembling shall seize them unto the ends of the earth. 6 And the high mountains shall be shaken, And the high hills shall be made low, And shall melt like wax before the flame 7 And the earth shall be wholly rent in sunder, And all that is upon the earth shall perish, And there shall be a judgement upon all (men). 8 But with the righteous He will make peace. -

Arthur Miller's Contentious Dialogue with America

Louise Callinan Revered Abroad, Abused at Home: Arthur Miller’s contentious dialogue with America A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at St Patrick’s College, Dublin City University Supervisor: Auxiliary Supervisor: Dr Brenn a Clarke Dr Noreen Doody Dept of English Dept of English St Patrick’s College St Patrick’s College Drumcondra Drumcondra May 2010 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has-been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: Qoli |i/U i/|______________ ID No.: 55103316 Date: May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever indebted to Dr. Brenna Clarke for her ‘3-D’ vision, and all that she has so graciously taught me. A veritable fountain of knowledge, encouragement, and patient support, she- has-been a formative force to me, and will remain a true inspiration. Thank you appears paltry, yet it is deeply meant and intended as an expression of my profound gratitude. A sincere and heartfelt thank you is also extended to Dr. Noreen Doody for her significant contribution and generosity of time and spirit. Thank you also to Dr. Mary Shine Thompson, and the Research Office. A special note to Sharon, for her encyclopaedic knowledge and ‘inside track’ in negotiating the research minefield. This thesis is an acknowledgement of the efforts of my family, and in particular the constant support of my parents. -

About Sanctification, Not Justification

S E V E N A 7 1 Seven Key Truths Foundational Principles for the New Testament Church Robert Ewing & Glenn Ewing This work is property of the Grace New Testament Ministries Foundation, whose mission includes the publishing and distribution of the writings and teachings of Robert Ewing and others that have the desire to see the restoration of the Church according to the New Testament pattern. All royalties obtained trough the sale of this book will be used to fulfill this mission. All scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the King James Version. Permission is granted to reproduce brief quotations or parts of this book without the prior permission of the Foundation so long as the content remains unaltered an the title and author’s name are men- tioned. Rights for publishing this book in other languages are con- tracted by the Grace New Testament Ministries Foundation. Second edition: 2000 Third edition: 2006 Copies printed:1000 ISBN 968-7756-18-7 Ediciones Ariel ® Francisco G. Sada 2400 Col. María Luisa Monterrey, NL 64040 México www.edicionesariel.com Impreso en México Printed in Mexico 2 "For though ye have ten thousand instructors in Christ, yet have ye not many fathers..." (1 Corinthians 4:15). Brother Robert Ewing was more than a teacher of the Word to me; he was the one that the Lord used to shape my spiritual walk. I had been a believer for more than 17 years before I met Brother Robert, and I had a desire to serve God, but I was also very entrenched in legalism. -

100 Years on the Road, 108 a Christmas Carol, 390 a Cool Million, 57 a Memory of Two Mondays, 6, 129, 172, 173, 200, 211 a Natio

Cambridge University Press 0521844169 - Arthur Miller: A Critical Study Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX 100 Years on the Road,108 Ann Arbor, 12 Anna Karenina,69 A Christmas Carol,390 Anti-Semitism, 13, 14, 66, 294, 330, A Cool Million,57 476, 485, 488 AMemoryofTwoMondays,6,129,172, Apocalypse Now,272 173, 200, 211 Arden, John, 157 A Nation of Salesmen,107 Arendt, Hannah, 267, 325 APeriodofGrace, 127 Arnold, Eve, 225 A Search for a Future,453 Aronson, Boris, 251 A Streetcar Named Desire, 98, 106, 145 Artaud, Antonin, 283 A View from the Bridge, 157, 173, 199, Arthur Miller Centre, 404 200, 202, 203, 206, 209, 211, 226, Auschwitz–Birkenau, 250, 325, 329, 351, 459 471 Abel, Lionel, 483 Awake and Sing, 13, 57, 76 Actors Studio, 212 Aymee,´ Marcel, 154, 156 Adorno, Theodore, 326 After the Fall, 5, 64, 126, 135, 166, 203, ‘Babi Yar’, 488 209, 226, 227, 228, 248, 249, 250, Barry, Phillip, 18 257, 260, 264, 267, 278, 280, 290, Barton, Bruce, 427 302, 308, 316, 322, 327, 329, 331, BBC, 32 332, 333, 334, 355, 374, 378, 382, Beckett, Samuel, 120, 175, 199, 200, 386, 406, 410, 413, 415, 478, 487, 488 204, 209, 250, 263, 267, 325, 328, Alger, Horatio Jr., 57, 113 329, 387, 388, 410, 475 All My Sons,1,13,17,42,47,64,76,77, Bel-Ami,394 98, 99, 132, 136, 137, 138, 140, 197, Belasco, David, 175 288, 351, 378, 382, 388, 421, 432, 488 Bell, Daniel, 483 Almeida Theatre, 404, 416 Bellow, Saul, 74, 236, 327, 372, 376, Almost Everybody Wins,357 436, 470, 471, 472, 473, 483 American Clock, The, 337 Belsen, 325 American Federation of Labour, 47 -

Arthur Miller Roxbury, Connecticut, Which Would Become His Long Time Home

Guild's National Award. During 1944 Miller toured army camps to collect background material for his 1945 screenplay, The Story of GI Joe. In 1947 Miller's Name play, All My Sons, was produced and won the New York Critics' Circle Award and two Tony Awards. As his success continued, Miller made the decision in 1948 to build a studio in Arthur Miller Roxbury, Connecticut, which would become his long time home. It was in this studio where he wrote the play that brought him international fame, Death of a By Jamie Kee Salesman. This play was considered a major achievement and has become a classic in American and world theatre. On February 10, 1949, the play premiered on Broadway at the Morosco Theatre. Miller's Death of a Salesman won a Tony Born on October 17, 1915, American playwright Award for best play, the New York City Drama Circle Critics' Award, and the Arthur Miller was a major figure in the American Pulitzer Prize for drama. This was the first time a play won all three of these major theatre and cinema. He was best known for his play, awards. Death of a Salesman, and for his marriage to actress Marilyn Monroe. Miller wrote other plays such as During the 1950s the United States Congress began investigating Communist The Crucible, A View from the Bridge, and All My influence in the arts. Miller compared these investigations to the witch trials of Sons, all of which are still performed and studied 1692, so he traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, to do research. -

Production History Organized by Season

Great Lakes Theater: Production History Organized By Season Year Author Title Director Run Dates 1962-1965 *Lakewood Civic Auditorium *Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival Born *Artistic Director: Arthur Lithgow Rotating Repertory 1962 Shakespeare, William As You Like It Lithgow, Arthur July 11 - Sept 6 1962 Shakespeare, William Richard II Gruenewald, Tom July 28 - Sept 8 1962 Shakespeare, William Othello Lith + Grue, co-dir July 18 - Sept 7 1962 Shakespeare, William Henry IV, Part I Lithgow, Arthur Aug 11 - Sept 9 1962 Shakespeare, William Henry IV, Part II Lithgow, Arthur Aug 11 - Sept 9 1962 Shakespeare, William The Merchant of Venice Lithgow, Arthur Aug 22 - Sept 9 Rotating Repertory 1963 Shakespeare, William Comedy of Errors Lithgow, Arthur June 25 - Sept 13 1963 Shakespeare, William Romeo and Juliet Lithgow, Arthur July 2 - Sept 13 1963 Shakespeare, William The Merry Wives of Windsor Moffatt, Donald July 9 - Sept 13 1963 Shakespeare, William Henry V Lithgow, Arthur July 23 - Sept 13 1963 Shakespeare, William Julius Caesar Moffatt, Donald July 30 - Sept 13 1963 Shakespeare, William Measure for Measure (designer also directed) Lithgow, Arthur Aug 13 - Sept 13 Rotating Repertory 1964 Shakespeare, William The Taming of the Shrew Lithgow, Arthur June 30 - Sept 19 1964 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Lithgow, Arthur July 7 - Sept 19 1964 Shakespeare, William Much Ado About Nothing George, Hal July 14 - Sept 19 1964 Shakespeare, William Henry VI Siletti, Mario July 28 - Sept 19 1964 Shakespeare, William Richard III Earle, Edward August 4 - Sept 19 1964 Shakespeare, William Antony and Cleopatra George, Hal August 18 - Sept 19 Rotating Repertory 1965 Shakespeare, William Macbeth Lithgow, Arthur June 25 - Sept 25 1965 Sheridan, Richard Brinsley The Rivals Siletti, Mario June 29 - Sept 25 1965 Shakespeare, William A Midsummer Night's Dream Hooks, David July 13 - Sept 25 1965 Moliere + Chekhov, Anton The School for Wives + Marriage Proposal Linville, Larry/Lithg. -

![1B Anthropology [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2814/1b-anthropology-pdf-3302814.webp)

1B Anthropology [PDF]

B. ANTHROPOLOGY In this part of dogmatics we treat of 1. Man's present abode. 2. Man's nature. 3. Image of God. 4. Fall of man. 5. Sin. 1. Man's Present Abode I. The universe was created by God in the beginning to be the home of man. 1. The Creator is God, particularly the Father. a) God, the Triune God, is the Creator. Gn 1:1-2:3 Note: Gn 2:4-25 is not a second account of creation but a chapter of the world's history following creation. References in it to creation must be understood in the light of chapter 1. Phillip Hefner: A number of scholars have classified the myths of creation in the world’s religions. Charles Long, for example, has provided five different categories of such myths: emergence myths, world-parent myths, myths of creation from chaos and from the cosmic egg, creation from nothing, and earth- diver myths. Within the creation-from-nothing classification, he gathers the following: the Australian myth of the Great Father, Hesiod, Rig Veda, the ancient Maya myth from the Popol Vuh, and myths from Polynesia, the Maori, the Tuamotua, the Egyptians, and the Zuni- in addition to the Hebrew myth from Genesis…. Scholars are nearly unanimous that Genesis 1-11 is put together from several literary accounts. The one called “J” begins with Gen 2:4 and continues off and on through chapter 11. The other called “P” begins with the first chapter (Braaten/Jenson, Christian Dogmatics, I, p 277-278, 280). _____ 2 Kings 19:15 Hezekiah prayed to the LORD: “O LORD, God of Israel, enthroned between the cherubim, you alone are God over all the kingdoms of the earth. -

The Ithacan, 1992-04-09

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1991-92 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 4-9-1992 The thI acan, 1992-04-09 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1991-92 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1992-04-09" (1992). The Ithacan, 1991-92. 27. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1991-92/27 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1991-92 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. .PreJudlce In the news media: ABC Journallstlc Integrity: the tricky Five commissioned works premiere at aJ1chor.dellberates Its long history challenges facing student Journallsts New York City's Lincoln Center •• pages ... page 10 ... page 13 The ITHACAN The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Vol. 59, No. 26 Thursday, April 9, 1992 28 pages Free Low turnout keys landslide election wins By Sabina Rogers sion, the only official party on the which came in second place with 14 for the students of IC. sify the library's resources by ask On Wednesday, April 8, Jane ballot, to the Executive Board of votes, had presidential candidate Kolp said one of the goals the ing for more materials about gays, White '92, Chair of the Elections Student Government. Jerry Brown on the ballot for presi Board has is to help set up a schol blacks and other subject matters for Committee, ·read the results of the The Executive Board for '92- dent of the Executive Board. -

Religion Five Years After the Crucible Was First Produced, Historian Edmund S

Religion Five years after The Crucible was first produced, historian Edmund S. Morgan offered this trenchant summary of Puritanism’s inherent religious tensions: Puritanism required that a man devote his life to seeking salvation but told him he was helpless to do anything but evil. Puritanism required that he rest his whole hope in Christ but taught him that Christ would utterly reject him unless before he was born God had foreordained his salvation. Puritanism required that man refrain from sin but told him that he would sin anyhow. Puritanism required that he reform the world in the image of God’s holy kingdom but taught him that the evil of the world was incurable and inevitable. Puritanism required that he work to the best of his ability at whatever task was set before KLP DQG SDUWDNH RI WKH JRRG WKLQJV WKDW *RG KDG ¿OOHG WKH ZRUOG with but told him he must enjoy his work and his pleasures only, as it ZHUHDEVHQWPLQGHGO\ZLWKKLVDWWHQWLRQ¿[HGRQ*RG Miller’s play reflects this constellation of paradoxes in its characters’ earnest seeking after truth despite their blindness to their own ignorance, their determination to root out evil wherever they might find it except in their own assumptions and beliefs, and in their longing for a perfectly moral life that would dominate their irrepressible human passions. For them, the devil was a spiritual reality that encompassed these and other barriers to a pious and godly life. As Miller himself commented, religious faith is central to the play’s intent: The form, the shape, the meaning of The Crucible were all compounded out of the faith of those who were hanged.