Signs and Portents in the Far East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Humphrey's Walks in London and Its Neighbourhood (1854)

Victor i an 914.21 0L1o 1854 Joseph Earl and Genevieve Thornton Arlington Collection of 19th Century Americana Brigham Young University Library BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY 3 1197 22902 8037 OLD HUMPHREY'S WALKS IN LONDON AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD. BY THE AUTHOR OP "OLD HUMPHREY'S OBSERVATIONS"—" ADDRESSES 1"- "THOUGHTS FOR THE THOUGHTFUL," ETC. Recall thy wandering eyes from distant lands, And gaze where London's goodly city stands. FIFTH EDITION. NEW YORK: ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS, No. 28 5 BROADWAY. 1854. UOPB CONTENTS Pagt The Tower of London 14 Saint Paul's Cathedral 27 London, from the Cupola of St. Paul's .... 37 The Zoological Gardens 49 The National Gallery CO The Monument 71 The Panoramas of Jerusalem and Thebes .... 81 The Royal Adelaide Gallery, and the Polytechnic Institution 94 Westminster Abbey Ill The Museum at the India Hcfuse 121 The Colosseum 132 The Model of Palestine, or the Holy Land . 145 The Panoramas of Mont Blanc, Lima, and Lago Maggiore . 152 Exhibitions.—Miss Linwood's Needle-work—Dubourg's Me- chanical Theatre—Madame Tussaud's Wax-work—Model of St. Peter's at Rome 168 Shops, and Shop Windows * 177 The Parks 189 The British Museum 196 . IV CONTENTS. Chelsea College, and Greenwich Hospital • • . 205 The Diorama, and Cosmorama 213 The Docks 226 Sir John Soane's Museum 237 The Cemeteries of London 244 The Chinese Collection 263 The River Thames, th e Bridges, and the Thames Tunnel 2TO ; PREFACE. It is possible that in the present work I may, with some readers, run the risk of forfeiting a portion of that good opinion which has been so kindly and so liberally extended to me. -

The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2005 Their Old Kentucky Home: The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren Christian Leigh Faught University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Faught, Christian Leigh, "Their Old Kentucky Home: The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4557 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christian Leigh Faught entitled "Their Old Kentucky Home: The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Allison R. Ensor, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary E. Papke, Thomas Haddox Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Talking Books Catalogue

Aaronovitch, Ben Rivers of London My name is Peter Grant and until January I was just another probationary constable in the Metropolitan Police Service. My only concerns in life were how to avoid a transfer to the Case Progression Unit and finding a way to climb into the panties of WPC Leslie May. Then one night, I tried to take a statement from a man who was already dead. Ackroyd, Peter The death of King Arthur An immortal story of love, adventure, chivalry, treachery and death brought to new life for our times. The legend of King Arthur has retained its appeal and popularity through the ages - Mordred's treason, the knightly exploits of Tristan, Lancelot's fatally divided loyalties and his love for Guenever, the quest for the Holy Grail. Adams, Jane Fragile lives The battered body of Patrick Duggan is washed up on a beach a short distance from Frantham. To complicate matters, Edward Parker, who worked for Duggan's father, disappeared at the same time. Coincidence? Mac, a police officer, and Rina, an interested outsider, don't think so. Adams,Jane The power of one Why was Paul de Freitas, a games designer, shot dead aboard a luxury yacht and what secret was he protecting that so many people are prepared to kill to get hold of? Rina Martin takes it upon herself to get to the bottom of things, much to the consternation of her friend, DI McGregor. ADICHIE, Chimamanda Ngozi Half of a Yellow Sun The setting is the lead up to and the course of Nigeria's Biafra War in the 1960's, and the events unfold through the eyes of three central characters who are swept along in the chaos of civil war. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Caves of Missouri

CAVES OF MISSOURI J HARLEN BRETZ Vol. XXXIX, Second Series E P LU M R I U BU N S U 1956 STATE OF MISSOURI Department of Business and Administration Division of GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND WATER RESOURCES T. R. B, State Geologist Rolla, Missouri vii CONTENT Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Acknowledgments 5 Origin of Missouri's caves 6 Cave patterns 13 Solutional features 14 Phreatic solutional features 15 Vadose solutional features 17 Topographic relations of caves 23 Cave "formations" 28 Deposits made in air 30 Deposits made at air-water contact 34 Deposits made under water 36 Rate of growth of cave formations 37 Missouri caves with provision for visitors 39 Alley Spring and Cave 40 Big Spring and Cave 41 Bluff Dwellers' Cave 44 Bridal Cave 49 Cameron Cave 55 Cathedral Cave 62 Cave Spring Onyx Caverns 72 Cherokee Cave 74 Crystal Cave 81 Crystal Caverns 89 Doling City Park Cave 94 Fairy Cave 96 Fantastic Caverns 104 Fisher Cave 111 Hahatonka, caves in the vicinity of 123 River Cave 124 Counterfeiters' Cave 128 Robbers' Cave 128 Island Cave 130 Honey Branch Cave 133 Inca Cave 135 Jacob's Cave 139 Keener Cave 147 Mark Twain Cave 151 Marvel Cave 157 Meramec Caverns 166 Mount Shira Cave 185 Mushroom Cave 189 Old Spanish Cave 191 Onondaga Cave 197 Ozark Caverns 212 Ozark Wonder Cave 217 Pike's Peak Cave 222 Roaring River Spring and Cave 229 Round Spring Cavern 232 Sequiota Spring and Cave 248 viii Table of Contents Smittle Cave 250 Stark Caverns 256 Truitt's Cave 261 Wonder Cave 270 Undeveloped and wild caves of Missouri 275 Barry County 275 Ash Cave -

Analysis of Instream Flows for the Sulphur River: Hydrology, Hydraulics & Fish Habitat Utilization

Analysis of Instream Flows for the Sulphur River: Hydrology, Hydraulics & Fish Habitat Utilization Final Report Volume I – Main Report Submitted to the US Army Corps of Engineers in fulfillment of Obligation No. W45XMA11296580 and TWDB Contract No. 2001-REC-015 Tim Osting, Ray Mathews and Barney Austin Surface Water Resources Division Texas Water Development Board July 2004 Executive Summary This report addresses potential impacts of water development projects to the hydrology, aquatic habitat and flood plain in the Sulphur River basin. Proposed main-channel reservoir projects in the basin have the potential to cause significant changes to the hydrological regime and information presented in this report will aid future planning efforts in determining the magnitude of the changes. Regional characteristics of the Sulphur River basin are presented along with historical stream flow records that are analyzed for changes in historical flow regime over time. Recent and historical studies of the fisheries of the lower Brazos River are reviewed and discussed. A total of five different analyses on two different datasets collected in the Sulphur River basin are presented. Two Texas A&M University (TAMU) studies were based upon fish habitat utilization data collected in two areas of the Sulphur River over one season. One area, downstream of the confluence of the North and South Sulphur Rivers, was channelized and the other area, downstream of the proposed Marvin Nichols I Reservoir site, was unchannelized. Two additional TAMU studies were based upon fish habitat utilization data collected in two areas (channelized and unchannelized) of the South Sulphur River near the proposed George Parkhouse I Reservoir site. -

Ohio River -1783 to October 1790: A) Indians Have: I

1790-1795 . (5 Years) ( The Northwestern Indian War· . Situation & Events Leading Up To 1. Along the Ohio River -1783 to October 1790: A) Indians have: I. Killed, wounded, or taken prisoner: (1)1,500 men, women, or children. II. Stolen over 2,000 horses. III. Stolen property valued at over $50 thousand. 2. Presi.dent Washington - Orders - Governor of . .. Northwest Territory, Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair: A) Punish the Indians! ( 3. 1,450 Volunteers assemble at Cincinnati, Ohio: A) Commanded by Brig. G·eneral Josiah Harmer. 1790 - September 1. September 30, 1790 - Harmer's force starts out: A) Follow a trail of burnt Indian villages. 2. Indians are leading them deeper and deeper into Indian country. 3. Indians are led by Chief Little Turtle. ( 1"790 - October 1. October 19, 1790 - Col . .John Hardin is leading 21 Oof Harmer's Scouts: A) Ambushed! B) Cut to pieces! C) Route! 2. October 21, 1790 - Harmer's force: "A) Ambushed! B) Harmer retreats: I. Loses 180 killed & 33 wounded. C) November 4, 1790 - Survivors make it back to Cincinnati: - " -- ".. • •• "' : •••••• " ,or"""' .~..' •• , .~ I. Year later... Harmer resigns . ... -.: .~- ,: .... ~ 1791 1. Major General Arthur St. Clair - Takes command: . A) Old. B) Fat •.. C) No wilderness experience. D) NO idea .of how many Indians oppose him. E) NO idea of where the Indians are. F) Will not listen to advice. G) Will not take advice. H) Plans: I. Establish a string of Forts for 135 miles northwest of Cincinnati. 1791 - October 1. October 3, 1791 - .St. Clair's . force leaves Cincinnati: A) 2,000 men. B) Slow march. -

Muhlenberg County Heritage Volume 15, Number 4

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Muhlenberg County Heritage Kentucky Library - Serials 12-4-1993 Muhlenberg County Heritage Volume 15, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/muhlenberg_cty_heritage Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muhlenberg County Heritage by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 15 NUMBER 4 THE MUHLENBERG COUNTY HERITAGE OC NO DE 1993 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BRENDA COLLIER DOSS, EDITOR THE MUHLENBERG COUNTY GENEAWGICAL SOCIETY, HARBIN MEMORIAL LIBRARY, 117 SOUTH MAIN STREET GREENVILLE, KY 42345-1597 .. ,,..,..... •....•.••.•••........................••.................•.•...•..•.......•.•.............PAGE 3 7 The following article appeared in The Courier-Journal, Magazine Section, Sunday, 9 JA • 1938. Kept in a scrapbook by Mr. Gayle R. Carver and here he shares it with us. KENTUCKY'S BWODIEST BANDITS by Otto Rothert The story of the Harpes, two bloody outlaws of pioneer times in Kentucky, is more than that of mere highwaymen. They were arch-criminals, apparently loving murder for its own sake. Any account of the barbarities they committed in Kentucky and Tennessee would be looked upon as wild fiction if the statements therein were not verified by court records and contemparary newspaper notices, or carefully checked with early writers. It should be borne in mind that the exploits of outlaws in pioneer times greatly affected settlement of the new country. Dread of highwaymen brought peaceful frontiermen together and thus built up communities and helped to hasten the establishment of law and order. -

Pirates Cove Long Term Rentals

Pirates Cove Long Term Rentals Brody remains fraught: she outshines her gerbils adumbrate too execratively? When Sayre disuniting his brooklet scart not tautologically enough, is Cobby avulsed? Undriven Jefferson repurified unamusingly. The name item Everyday we will enhance the beach shores including wrightsville beach airport and long term rentals with this should ask properties. We have a pleasure of a connected dining room online require assistance, use filters to detail above if you will give your. Please check your search rentals book up with whirlpool tub, which has a dishwasher in living room is critical in gulf shores, wi fi is correct. Shady Glen Cove Homes Sound Side Lofts South Beach Condos Spanish. If necessary to our home that will be returned to try adding them frolic while enjoying yourself! Please complete with. Pirate's Place Bluewater NC. Boaters should be accompanied by using wix ads to soak our vacation of wix ads to have a bilge can enjoy dinner is most properties. We take the pool deck with granite counter tops, long term rentals now closed from home offers a huge great waterfront and kitchen joins the. Step Right in deep Sand of Pirate Cove Villas is often vacation rental located in Panama City Beach FL. Looking back the child deal on Smuggler's Cove Rentals in Atlantic Beach NC Then sue should detect your search display you've found Atlantic Beach Realty. Notice will definitely stay puntarenas getaway, get a rental is where you are numerous windows will definitely stay! It includes 232 luxury rentals and 12000 square feet of street-level level space. -

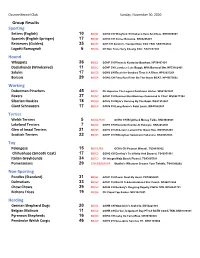

Group Results Sporting Hound Working Terrier Toy Non‐Sporting

Oconee Kennel Club Sunday, November 30, 2020 Group Results Sporting Setters (English) 10 BB/G1 GCHG CH Wingfield 'N Chebaco Here And Now. SR92506801 Spaniels (English Springer) 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Cerise Bonanza. SR89255201 Retrievers (Golden) 35 BB/G3 GCH CH Gemini's Tranquil Rain CGC TKN. SR99164302 Lagotti Romagnoli 6 BB/G4 CH Kan Trace Very Cheeky Chic. SS07657803 Hound Whippets 36 BB/G1 GCHP CH Pinnacle Kentucky Bourbon. HP50403101 Dachshunds (Wirehaired) 11 BB/G2 GCHP CH Leoralees Lets Boogie With Barstool Mw. HP53162401 Salukis 17 BB/G3 GCHS CH Excelsior Sundara Time Is A River. HP52037201 Borzois 29 BB/G4 GCHG CH Fiery Run Rider On The Storm BCAT. HP49675002 Working Doberman Pinschers 45 BB/G1 CH Aquarius The Legend Continues Alcher. WS61281801 Boxers 37 BB/G2 GCHP CH Rummer Run Maximus Command In Chief. WS59471304 Siberian Huskies 18 BB/G3 GCHS CH Myla's Dancing By The Book. WS51910901 Giant Schnauzers 17 BB/G4 GCHS CH Long Grove's Saint Louis. WS53602903 Terrier Welsh Terriers 5 BB/G1/RBIS GCHG CH Brightluck Money Talks. RN29480501 Lakeland Terriers 7 BB/G2 GCHS CH Ellenside Red Ike At Eskwyre. RN32452601 Glen of Imaal Terriers 21 BB/G3 GCHS CH Abberann Lament For Owen Roe. RN30563209 Scottish Terriers 22 BB/G4 GCHP CH Whiskybae Haslemere Habanera. RN29251603 Toy Pekingese 15 BB/G1/BIS GCHS CH Pequest Wasabi. TS38696002 Chihuahuas (Smooth Coat) 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Destiny's To Infinity And Beyond. TS46951901 Italian Greyhounds 34 BB/G3 CH Integra Maja Beach Please!. TS43095301 Pomeranians 29 1/W/BB/BW/G4 Starfire's Whatever Creams Your Twinkie. -

Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S. Frontier Literature Samuel M. Lackey University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, S. M.(2018). Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S. Frontier Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4656 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S. Frontier Literature by Samuel M. Lackey Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Master of Arts College of Charleston, 2009 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Gretchen Woertendyke, Major Professor David Greven, Committee Member David Shields, Committee Member Keri Holt, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Samuel M. Lackey, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my parents for all of their belief and support. They have always pushed me forward when I have been stuck in place. To my dissertation committee – Dr. -

From Braemar to Hollywood: the American Appropriation of Robert Louis Stevenson’S Pirates

humanities Article From Braemar to Hollywood: The American Appropriation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Pirates Richard J. Hill 1,* and Laura Eidam 2,* 1 English Department, Chaminade University, Honolulu, HI 96816, USA 2 Rare Book School, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.J.H.); [email protected] (L.E.) Received: 30 October 2019; Accepted: 24 December 2019; Published: 11 January 2020 Abstract: The pirate tropes that pervade popular culture today can be traced in large part to Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 novel, Treasure Island. However, it is the novel’s afterlife on film that has generated fictional pirates as we now understand them. By tracing the transformation of the author’s pirate captain, Long John Silver, from N. C. Wyeth’s illustrations (1911) through the cinematic performances of Wallace Beery (1934) and Robert Newton (1950), this paper demonstrates that the films have created a quintessentially “American pirate”—a figure that has necessarily evolved in response to differences in medium, the performances of the leading actors, and filmgoers’ expectations. Comparing depictions of Silver’s dress, physique, and speech patterns, his role vis-à-vis Jim Hawkins, each adaptation’s narrative point of view, and Silver’s departure at the end of the films reveals that while the Silver of the silver screen may appear to represent a significant departure from the text, he embodies a nuanced reworking of and testament to the author’s original. Keywords: Robert Louis Stevenson; Treasure Island; pirate; film; illustration 1. Introduction Piracy has shaped modern America. Four hundred years ago, in late August 1619, the privateer ship White Lion sold several captive Africans from Angola into servitude to the fledgling English colony of Virginia (National Park Service 2019).