Knoydart Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KNOYDART a Two-Day Bothy Adventure in the Wilderness of the Rough Bounds

KNOYDART A two-day bothy adventure in the wilderness of the Rough Bounds Overview The so-called 'Rough Bounds' of Knoydart – often described as Britain's last wilderness – are difficult to reach. Getting to the start of the route involves either a boat trip or long car journey along a winding, 20 mile single-track road. Cut off from the UK road network, the peninsula is a wild place of rugged mountains, remote glens and fjord-like sea lochs. This spectacular area includes three Munros and its coastal views take in Skye and the islands of the Inner Hebrides. In the 19th century, the peninsula fell victim to the Highland clearances but since 1999, after huge fundraising efforts, the land has been owned and managed by its own small community. Some days you won’t bump into another soul in here – although you may spot minke whales, eagles, otters and stags. Despite its inaccessibility, there are good paths connecting the glens and these provide exceptional running through challenging terrain. This fastpacking circuit is a wonderful way to immerse yourself in the unique landscape. Highlights • A truly special wilderness experience in a remote and spectacular location • A superb route on a legacy network of well-made paths through wild terrain • Spectacular views of rugged mountain and coastal scenery • Plentiful wildlife including red deer, otters, pine martens and birds of prey such as golden eagles • An overnight stay or wild camp at Sourlies bothy • Fantastic running, descending off the passes and along loch-side paths. Top tips • Be prepared for a serious run in a remote area with limited escape options. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Family Tree Maker

The Bloodline of the MacTavish Chiefs Generation No. 1 1. King of Connacht Eochaidh1 Muighmheadhoin1. Notes for King of Connacht Eochaidh Muighmheadhoin: Copyright: Patricia Adams, July 1, 2000, USA Please keep in mind that the pedigree of Clan MacTavish reaching this far back in history is in ancient times. There are no existing birth records, death records, etc., with the exception of the ancient annals and chronicles. There were no computers, no CDs, no microfilm, etc. Not everyone could read and write. The name of the same person was many times spelled differently by different scribes. We have to depend on the Annals of the Four Master, Annals of Ulster, Annals of Tigernach, and these records often time disagree on the year of the event. Later published materials may have picked up on incorrect information, or may have found newer documentation. Clans may very well have changed pedigrees over the years, sometimes because they learned of factual information and sometimes because they simply took advantage to change the line of a Chief to what they felt was a loftier claim. (The Clan Campbell, for example, changed their published Chief's line between 1975 and 1992.) I take this opportunity to caution you when reading history or pedigrees based on ancient documents or documents 1700, which may be written in another language (such as Latin) and call for translations. The line of any chief of a Clan (just as our personal family research) becomes speculation and opinion as you go back before the year 1000. Some of us in our own personal family research may not even be searchable before the year 1700. -

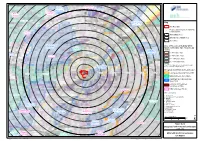

Designated and Protected Landscapes

29. Rhiddoroch - Beinn Dearg - Ben Wyvis Fannichs, 29. Rhiddoroch - Beinn Dearg Beinn Dearg - Ben Wyvis Ben Wyvis and Glencalvie 28. Fisherfield 27. Flowerdale - Letterewe - Shieldaig - Fannichs - Torridon ¬«1 Wester Ross Sutors of Cromarty, Key ¬«2 Rosemarkie and 3 ¬« Fort George ¬«4 Site Boundary ¬«11 !( Proposed Development 180m Tip 26. Coulin Height Turbine & Ledgowan Forest 45km Study Area ¬«10 25km Detailed Study Area ¬«8 ¬«5 5km Offset ¬«9 Strathconon, ¬«6 Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV): Monar and Glen Mullardoch Strathfarrar Number of Turbine Tips Theoretically Drynachan, Visible ¬«7 Lochindorb and Kyle - Dava Moors 1 - 5 Turbine Tips Plockton 24. Central 6 - 10 Turbine Tips Highlands 11 - 15 Turbine Tips 16 - 18 Turbine Tips The ZTV has been run on a bare ground model, Loch Ness and based on Terrain 5 Digital Terrain. Duntelchaig !( !( Designated and Protected Landscapes !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( 10km 20km 30km 40km 50km Kintail Glen Affric !( !( Cairngorms National Park (CNP) National Scenic Area (NSA) Highlands Special Landscape Area (SLA) Gardens and Designed Landscapes (GDL) 20. Wild Land Area (WLA) Monadhliath GDLs within 45 km Knoydart 1. Castle Leod 2. The Spa Gardens, Strathpeffer 3. Brahan 4. Fairburn The Cairngorm Mountains 5. Beaufort Castle 6. Dochfour Moidart, Morar 7. Aldourie Castle and Glen Shiel 8. Tomnahurich Cemetery 9. Leys Castle Ben Alder, Laggan 10. Culloden House 19. Braeroy - 18. Kinlochhourn - and Glen Banchor 11. Rosehaugh Loch Lochy Glenshirra - Knoydart - Morar (part in CNPA) 12. Achnacarry and Loch Oich Creag Meagaidh ¬«12 Scale 1:350,000 @ A3 Ben Alder, Km 0 5 10 15 ± Laggan and Ben Alder, Glen Banchor 15. Laggan and Cairngorms Glen Banchor Figure 8.2.2 Designated and Protected Landscapes with ZTV 14. -

History of the Macleods with Genealogies of the Principal

*? 1 /mIB4» » ' Q oc i. &;::$ 23 j • or v HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS. INVERNESS: PRINTED AT THE "SCOTTISH HIGHLANDER" OFFICE. HISTORY TP MACLEODS WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. Scot., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY AND GENEALOGIES OF THE CLAN MACKENZIE"; "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERON'S;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS ; " "THE " PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER ; " THE HISTORICAL TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLANDS;" "THE HISTORY " OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" " THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE IN 1882-83;" ETC., ETC. MURUS AHENEUS. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXXIX. J iBRARY J TO LACHLAN MACDONALD, ESQUIRE OF SKAEBOST, THE BEST LANDLORD IN THE HIGHLANDS. THIS HISTORY OF HIS MOTHER'S CLAN (Ann Macleod of Gesto) IS INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/historyofmacleodOOmack PREFACE. -:o:- This volume completes my fifth Clan History, written and published during the last ten years, making altogether some two thousand two hundred and fifty pages of a class of literary work which, in every line, requires the most scrupulous and careful verification. This is in addition to about the same number, dealing with the traditions^ superstitions, general history, and social condition of the Highlands, and mostly prepared after business hours in the course of an active private and public life, including my editorial labours in connection with the Celtic Maga- zine and the Scottish Highlander. This is far more than has ever been written by any author born north of the Grampians and whatever may be said ; about the quality of these productions, two agreeable facts may be stated regarding them. -

Kinlochhourne -Knoydart – Morar Wild Land Area

Description of Wild Land Area – 2017 18 Kinlochhourne -Knoydart – Morar Wild Land Area 1 Description of Wild Land Area – 2017 Context This very large area, extending 1065 km2 across Lochalsh and Lochaber, is the fourth most extensive WLA and only narrowly separated from the second largest, Central Highlands (WLA 24). It runs from Glen Shiel in the north and includes a large proportion of the Knoydart peninsula and the hills between Lochs Quoich, Arkaig and Eil and Eilt, and around the eastern part of Loch Morar. Major routes flank its far northern and southern edges, the latter to nearby Fort William, but it is otherwise distant from large population centres. It is one of only three mainland WLAs to be defined in part by the coast, on its western edge. The area contains in the north and west high, angular and rocky mountains with sweeping slopes towering over a series of steep sided glens and lochs, which extend into a more jumbled mass of rugged mountains within the central interior, with linear ranges of simpler massive hills in the east. These are formed of hard metamorphic rock that was carved during glaciation, creating features such as pyramidal peaks, corries, U-shaped glens, moraine and the remarkable fjords of Lochs Hourn and Nevis. Later erosion is also evident with the presence of burns, gorges, waterfalls and alluvial deposits. The distinctive landform features are highlighted against the open space and horizontal emphasis of adjacent sea and lochs. The WLA is largely uninhabited, apart from a few isolated crofts and estate settlements around the coast and loch shores. -

Western Scotland

Soil Survey of Scotland WESTERN SCOTLAND 1:250 000 SHEET 4 The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 SOIL SURVEY OF SCOTLAND Soil and Land Capability for Agriculture WESTERN SCOTLAND By J. S. Bibby, BSc, G. Hudson, BSc and D. J. Henderson, BSc with contributions from C. G. B. Campbell, BSc, W. Towers, BSc and G. G. Wright, BSc The Macaulay Institute for Soil Rescarch Aberdeen 1982 @ The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen, 1982 The couer zllustralion is of Ardmucknish Bay, Benderloch and the hzlk of Lorn, Argyll ISBN 0 7084 0222 4 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS ABERDEEN Contents Chapter Page PREFACE vii ACKNOWLEDGE~MENTS ix 1 DESCRIPTIONOF THEAREA 1 Geology, landforms and parent materials 2 Climate 12 Soils 18 Principal soil trends 20 Soil classification 23 Vegetation 28 2 THESOIL MAP UNITS 34 The associations and map units 34 The Alluvial Soils 34 The Organic Soils 34 The Aberlour Association 38 The Arkaig Association 40 The Balrownie Association 47 The Berriedale Association 48 The BraemorelKinsteary Associations 49 The Corby/Boyndie/Dinnet Associations 49 The Corriebreck Association 52 The Countesswells/Dalbeattie/PriestlawAssociations 54 The Darleith/Kirktonmoor Associations 58 The Deecastle Association 62 The Durnhill Association 63 The Foudland Association 66 The Fraserburgh Association 69 The Gourdie/Callander/Strathfinella Associations 70 The Gruline Association 71 The Hatton/Tomintoul/Kessock Associations 72 The Inchkenneth Association 73 The Inchnadamph Association 75 ... 111 CONTENTS -

The Charitable Destruction of a Community Asset

THE CHARITABLE DESTRUCTION OF A COMMUNITY ASSET Background Walkers and members of the deer management community have been shocked and stunned by the recent discovery of large numbers of deer culled and left to rot on the isolated property of Li & Coire Dhorcail on the north west coast of Knoydart. Some had haunches removed, and others were found beheaded where they fell. The scale is such that the incident is effectively a major wildlife crime in everything but name. It has not been carried out by a rogue landlord or estate, but by an environmental NGO, the John Muir Trust (JMT). The numbers are not known because the information has not been fully disclosed, but 86 red deer stags have been culled this summer, and JMT admit the majority have not been retrieved. Given the difficulty of accessing the area and removing deer carcases, it is likely that almost all of these animals will have been left lying where they were shot. A huge amount of manpower will have been required to do this, and such input will have required strategic direction. Such an incident removes a potential income of about £100,000 from the wider community, a sum they can ill afford to do without. It cannot be justified as providing food for golden eagles or helping woodland regeneration. On the former, a deer carcase left on the hill in winter will feed an eagle for several months. In summer, they will rot away in a few weeks. On the latter, the small area of woodland regeneration that JMT seeks to expand has no strategic national or local significance, and is out of all proportion to the cost Stag carcasses abandoned by JMT being extracted in terms of the numbers of animals which have to be killed. -

Aspects of the Religious History of Lewis

ASPECTS OF THE RELIGIOUS HISTORY OF LEWIS Rev. Murdo Macaulay was born in Upper Carloway, Lewis, the eldest child of a family of four boys and two girls. On the day of his birth the famous and saintly Mrs Maclver of Carloway predicted that he was to be a minister of the Gospel. This prediction, of which he had been informed, appeared to have no particular bearing upon his early career. It was not until the great spiritual revival, which began in the district of Carloway a few years before the outbreak of the Second Worid War, that Mr Macaulay came to a saving knowledge of the Lord Jesus Christ. Whatever thoughts he may have entertained previously, it was in a prisoner of war camp in Germany that he publicly made known his decision to respond to his call to the ministry of the Free Church. The Lord's sovereignty in preparing him for the ministry could make interesting reading. It included a full secondary education, a number of years of military training, some years in business where he came to understand the foibles of the public whom he had to serve, a graduation course at Edinburgh University and a divinity Course in Up to the Disruption of 1843 the Free Church College. Mr Macaulay has a studious mind, a retentive memory, and scholastic ability for research. He has a good working knowledge of six languages, yet he is more concerned about stating facts than about This document is scanned for research and appears never to have been clothing them in attractive language. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

The Earl Marischal 1717. THE

Walker & Boutall ph. Sc, The Earl Marischal 1717. THE COMPANIONS OF PICKLE BEING A SEQUEL TO ‘PICKLE THE SPY’ BY THE SAME AUTHOR. PICKLE THE SPY; or, The Incognito of Prince Charles. With 6 portraits 8vo. 18s. ST. ANDREWS. With 8 Plates and 21 Illustrations in the Text by T. HODGE. 8vo. 15s. net. THE MAKING OF RELIGION. 8vo. 12s. MODERN MYTHOLOGY: a Reply to Professor Max Müller. 8vo. 9s. HOMER AND THE EPIC. Crown 8vo. 9s. net. CUSTOM AND MYTH: Studies of Early Usage and Belief. With 18 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. LETTERS TO DEAD AUTHORS. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net. BOOKS AND BOOKMEN. With 2 Coloured Plates and 17 Illustrations. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net. OLD FRIENDS. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net. LETTERS ON LITERATURE. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net. GRASS OF PARNASSUS. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net. ESSAYS IN LITTLE. With Portrait of the Author. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. COCK LANE AND COMMON-SENSE. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. THE BOOK OF DREAMS AND GHOSTS. Crown 8vo. 6s. ANGLING SKETCHES. With 20 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. A MONK OF FIFE: a Story of the Days of Joan of Arc. With 13 Illustrations by SELWYN IMAGE. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO., 39 Paternoster Row, London New York and Bombay. THE COMPANIONS OF PICKLE BEING A SEQUEL TO ‘PICKLE THE SPY’ BY ANDREW LANG WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON NEW YORK AND BOMBAY 1898 All rights reserved Contents PREFACE .......................................................................... vi ILLUSTRATIONS .............................................................. vi II THE EARL IN PRUSSIAN SERVICE ........................... 34 III MURRAY OF BROUGHTON ..................................... -

Natural Heritage Zones: a National Assessment of Scotland's

NATURAL HERITAGE ZONES: A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF SCOTLAND’S LANDSCAPES Contents Purpose of document 6 An introduction to landscape 7 The role of SNH 7 Landscape assessment 8 PART 1 OVERVIEW OF SCOTLAND'S LANDSCAPE 9 1 Scotland’s landscape: a descriptive overview 10 Highlands 10 Northern and western coastline 13 Eastern coastline 13 Central lowlands 13 Lowlands 13 2 Nationally significant landscape characteristics 18 Openness 18 Intervisibility 18 Naturalness 19 Natural processes 19 Remoteness 19 Infrastructure 20 3 Forces for change in the landscape 21 Changes in landuse (1950–2000) 21 Current landuse trends 25 Changes in development pattern 1950–2001 25 Changes in perception (1950–2001) 32 Managing landscape change 34 4 Landscape character: threats and opportunities 36 References 40 PART 2 LANDSCAPE PROFILES: A WORKING GUIDE 42 ZONE 1 SHETLAND 43 1 Nature of the landscape resource 43 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 51 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 51 4 Building a sustainable future 53 ZONE 2 NORTH CAITHNESS AND ORKNEY 54 Page 2 11 January, 2002 1 Nature of the landscape resource 54 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 72 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 72 4 Building a sustainable future 75 ZONE 3 WESTERN ISLES 76 1 Nature of the landscape resource 76 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 88 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 89 4 Building a sustainable future 92 ZONE 4 NORTH WEST SEABOARD 93 1 Nature of the landscape resource 93 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 107 3 Landscape and trends