Iosifidis and Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Liga Gets Its Wish for Season's Return

12 Wednesday, June 10, 2020 Sports LA LIGA GETS ITS WISH FOR SEASON’S RETURN Football is a culture and way of life in Spain, says Mendieta IKOLI VICTOR DOHA GAIZKA Mendieta, a former Qatar loves Spanish football Barcelona and Valencia player because it is attractive and says football is a culture and a loved all over the world. way of life in Spain which will be back with the return of La Former Barcelona & Valencia Liga on Thursday. player Gaizka Mendieta The Spaniard expressed his views in an online video conference organised by not affect players as a whole, Nizar Bakht of La Liga Global as he expects the players to Delegate in Qatar with the adjust to the new situation participation of Qatar-based after one or two games. journalists. Responding to a question Spain has been one of the about the influx of Spanish most affected countries with coaches in Qatar, the former more than 27,000 deaths re- Spanish international said, corded since the novel coro- “Qatar loves Spanish football navirus pandemic broke, but because it is attractive and Mendieta believes that the loved all over the world.” resumption of football will Mendieta added that the Barcelona’s French forward Antoine Griezmann, Guinea-Bissau forward Ansu Fati, French defender Samuel Umtiti, Argentine forward Lionel Messi and Chilean midfielder Arturo Vidal boost morale and show the successes of its club sides in attend a training session at the Ciutat Esportiva Joan Gamper in Sant Joan Despi, Spain. (AFP) country’s steadfastness and European competitions and love for the game. -

12 National Teams Will Participate in the Tournament, Represent

FAQs Participating Teams and Players How many teams will participate? 12 national teams will participate in the tournament, representing many of the biggest football nations on the planet to create a truly global competitive international tournament. How many players will be in each squad? Each Star Sixes squad will comprise ten players, six will be permitted to play at any one time with the other four being substitutes. When will the teams be confirmed and announced? The 12 countries have been confirmed - Brazil, China, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Nigeria, Portugal, Scotland and Spain. Who will manage the teams? Each Star Sixes team will have an appointed captain who will play and also manage the side. How are players chosen? The selection process is managed by the team captains and Star Sixes. When will players be announced? A galaxy of stars has already been announced, including: Roberto Carlos (Brazil), Steven Gerrard, Michael Owen, David James, Emile Heskey (England), Carles Puyol, Gaizka Mendieta (Spain), Michael Ballack (Germany), Deco (Portugal), Robert Pires (France), Jay-Jay Okocha (Nigeria) and Dominic Matteo (Scotland). Keep an eye on the Star Sixes website and social media for further player announcements in the coming weeks. What kit will the players wear? Players will wear national team colours, designed specifically for the Star Sixes tournament. Keep an eye on the Star Sixes website and social media to find out when the team kits will be revealed. Competition Format, Schedule and Rules What is the competition format? How do teams progress to the final? There will be three groups of four teams. -

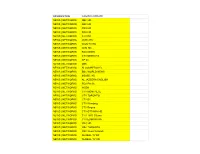

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

RETRATO Gaizka Mendieta Jugador Del Middlesbrough Joan Josep Pallàs

RETRATO Gaizka Mendieta Jugador del Middlesbrough Joan Josep Pallàs PERSONAL E INTRANSFERIBLE* Con la música a otra parte NOMBRE Y APELLIDOS Gaizka Mendieta Zabala ace un par de semanas, ju- prensa poco fidedigno, ven a un Mendieta en una de sus canciones FECHA Y LUGAR DE Hgando contra el Ports- periodista y levantan en un plis sin saber que el futbolista era fan NACIMIENTO mouth, a Gaizka Mendieta plas un fenomenal muro construi- suyo. Ahora mantienen una gran Nací el 27 de marzo de le sucedió lo que a Henrik Larsson. do a base de tópicos gastadísimos. amistad. Su afición le llevó a com- 1974 en Bilbao La rodilla se le fue para un lado y el Se atrincheran y dan la imagen de prarse una guitarra eléctrica con ESTADO CIVIL pie para otro, cayó lesionado de ser tipos desaboridos. No es su ca- la que practicaba tocando acordes Estoy casado con Carmina forma fortuita y le dieron un diag- so en absoluto. Detrás de esa facha- de sus canciones favoritas pero el y tengo dos hijas, Haize, nóstico equivocado. El médico del da de autodefensa se esconde una nacimiento de sus dos hijas ha aca- de 3 años, y Ariane, de 2 Middlesbrough le examinó la rodi- personalidad rica, repleta de in- bado con su carrera como instru- RELIGIÓN lla derecha y le habló de un esguin- quietudes, con la lectura y la músi- mentalista. Me he criado como ce y de dos o tres meses de baja. ca como principales debilidades. Es la de músico su segunda voca- católico y es lo que Al día siguiente médico y juga- Algo bueno tiene que haber en es- ción fallida. -

2011/12 UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook

Records With Walter Samuel grounded and goalkeeper Julio Cesar a bemused onlooker, Gareth Bale scores the first Tottenham Hotspur FC goal against FC Internazionale Milano at San Siro. The UEFA Champions League newcomers came back from 4-0 down at half-time to lose 4-3; Bale performed the rare feat of hitting a hat-trick for a side playing with 10 men; and it allowed English clubs to take over from Italy at the top of the hat-trick chart. PHOTO: CLIVE ROSE / GETTY IMAGES Season 2011/2012 Contents Competition records 4 Sequence records 7 Goal scoring records – All hat-tricks 8 Fastest hat-tricks 11 Most goals in a season 12 Fastest goal in a game 13 Fastest own goals 13 The Landmark Goals 14 Fastest red cards 15 Fastest yellow cards 16 Youngest and Oldest Players 17 Goalkeeping records 20 Goalless draws 22 Record for each finalist 27 Biggest Wins 28 Lowest Attendances 30 Milestones 32 UEFA Super Cup 34 3 UEFA Champions League Records UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE COMPETITION RECORDS MOST APPEARANCES MOST GAMES PLAYED 16 Manchester United FC 176 Manchester United FC 15 FC Porto, FC Barcelona, Real Madrid CF 163 Real Madrid CF 159 FC Barcelona 14 AC Milan, FC Bayern München 149 FC Bayern München 13 FC Dynamo Kyiv, PSV Eindhoven, Arsenal FC 139 AC Milan 12 Juventus, Olympiacos FC 129 Arsenal FC 126 FC Porto 11 Rosenborg BK, Olympique Lyonnais 120 Juventus 10 Galatasaray AS, FC Internazionale Milano, 101 Chelsea FC FC Spartak Moskva, Rangers FC MOST WINS SUCCESSIVE APPEARANCES 96 Manchester United FC 15 Manchester United FC (1996/97 - 2010/11) 89 FC -

UEFA Awards to Be Presented at Monaco Gala

Media Release Route de Genève 46 Case postale Communiqué aux médias CH-1260 Nyon 2 Union des associations Tel. +41 22 994 45 59 européennes de football Medien-Mitteilung Fax +41 22 994 37 37 uefa.com [email protected] Date: 22/08/2001 No. 131 - 2001 UEFA awards to be presented at Monaco Gala Europe’s top coaches have elected best players in 2000/01 UEFA club competitions It has become an annual tradition to present awards to top players during the UEFA Gala held in Monaco on the eve of the UEFA Super Cup match which brings together the two gold-medal sides in Europe. This year’s fixture pits the winners of the UEFA Champions League, FC Bayern München, against the UEFA Cup champions, Liverpool FC. Coaches from the top clubs in last season’s UEFA club competitions are invited to cast their votes for the best players – in five different categories – and the best coach. The nominees for the awards to be presented during the Gala on Thursday 23 August, with live television coverage by Eurosport as from 21.00 CET, are as follows: Best Goalkeeper Fabien Barthez (Manchester United FC) Santiago Cañizares (Valencia CF) Oliver Kahn (FC Bayern München) Best Defender Fabián Ayala (Valencia CF) Sammy Kuffour (FC Bayern München) Jaap Stam (Manchester United FC) Best Midfielder Luís Figo (Real Madrid CF) Gaizka Mendieta (Valencia CF – his club last season) Patrick Vieira (Arsenal FC) Best Forward Giovane Elber (FC Bayern München) Thierry Henry (Arsenal FC) Raúl González (Real Madrid CF) Most Valuable Player Stefan Effenberg (FC Bayern München) Gary McAllister (Liverpool FC) Raúl González (Real Madrid CF) The nominees for the Best Coach award are Vicente Del Bosque (Real Madrid CF), Ottmar Hitzfeld (FC Bayern München) and Gérard Houllier (Liverpool FC). -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

Liga Fertiberia De Fútbol Indoor

TRIPTICO.ai 6 11/03/2013 17:47:55 El espectáculo del Fútbol Indoor regresa en marzo con la VIVI ediciónedición dede lala LigaLiga FertiberiaFertiberia TRIPTICO.ai 4 11/03/2013 17:47:55 Liga Fertiberia de Fútbol Indoor Un año más la Asociación de Fútbol Indoor y Fertiberia llevarán el espectáculo a los pabellones deportivos de toda España con motivo de la sexta edición de la Liga Fertiberia de Fútbol Indoor. Se trata de una de las competiciones más singulares de cuantas se celebran en nuestro país, en la que cada año participan jugadores de elite con una larga trayectoria tanto nacional como internacional en un formato diferente, lleno de goles, emoción y especialmente desarrollado para promover el espectáculo. La Liga Fertiberia la componen diversos equipos integrados por miembros de las asociaciones de veteranos de los clubes que juegan en la LigaBBVA de fútbol. Son en su mayoría activos deportistas con una larga carrera en la elite profesional a sus espaldas, muchos de los cuales han ganado títulos internacionales y participado en Eurocopas y Mundiales. Esta temporada la Liga Fertiberia contará con nueve de los mejores equipos del panorama nacional, Real Madrid CF, FC Barcelona, Valencia CF, Atlético de Madrid, RCD Espanyol, Deportivo de La Coruña, Celta de Vigo, Real Valladolid, Málaga CF y a los que se une el FC Porto como club invitado. Estos diez conjuntos saltarán al campo dispuestos a conquistar un título que año tras año ha ido elevando su competitividad. Para ello cuentan con unos planteles de auténtico lujo donde destacan estrellas internacionales de la talla de Fernando Morientes, Djalminha, Gaby Moya, Luis Milla, Gaizka Mendieta, Jordi Lardín, Vlado Gudelj, Vitor Baia, Salva Ballesta o Isailovic. -

Candidates Short-Listed for UEFA Champions League Awards

Media Release Route de Genève 46 Case postale Communiqué aux médias CH-1260 Nyon 2 Union des associations Tel. +41 22 994 45 59 européennes de football Medien-Mitteilung Fax +41 22 994 37 37 uefa.com [email protected] Date: 29/05/02 No. 88 - 2002 Candidates short-listed for UEFA Champions League awards Supporters invited to cast their votes via special polls on uefa.com official website With the curtain now down on the 2001/02 club competition season, UEFA’s Technical Study Group has produced short-lists of players and coaches in three different categories and will select a ‘Dream Team’ to mark the tenth anniversary of Europe’s top club competition, based on performances in the UEFA Champions League since it was officially launched in 1992. As usual, they have put forward nominees to receive the annual awards presented at the UEFA Gala, held as a curtain-raiser to the new club competition season at the end of August to coincide with the draws for the opening stages of the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA Cup. They have named six candidates for each of the awards presented to the Best Goalkeeper, Best Defender, Best Midfielder, Best Attacker, Most Valuable Player and Best Coach, based on their performances during the 2001/02 European campaign. This is not restricted to the UEFA Champions League – which explains the inclusion of Bert van Marwijk, head coach of the Feyenoord side which carried off the UEFA Cup and will be in Monaco to contest the UEFA Super Cup with Real Madrid CF. -

Football Photos FPM01

April 2015 Issue 1 Football Photos FPM01 FPG028 £30 GEORGE GRAHAM 10X8" ARSENAL FPK018 £35 HOWARD KENDALL 6½x8½” EVERTON FPH034 £35 EMLYN HUGHES 6½x8½" LIVERPOOL FPH033 £25 FPA019 £25 GERARD HOULLIER 8x12" LIVERPOOL RON ATKINSON 12X8" MAN UTD FPF021 £60 FPC043 £60 ALEX FERGUSON BRIAN CLOUGH 8X12" MAN UTD SIGNED 6½ x 8½” Why not sign up to our regular Sports themed emails? www.buckinghamcovers.com/family Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF FPM01 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] Manchester United FPB002 £50 DAVID BECKHAM FPB036 NICKY BUTT 6X8” .....................................£15 8X12” MAGAZINE FPD019 ALEX DAWSON 10X8” ...............................£15 POSTER FPF009 RIO FERDINAND 5X7” MOUNTED ...............£20 FPG017A £20 HARRY GREGG 8X11” MAGAZINE PAGE FPC032 £25 JACK CROMPTON 12X8 FPF020 £25 ALEX FERGUSON & FPS003 £20 PETER SCHMEICHEL ALEX STEPNEY 8X10” 8X12” FPT012A £15 FPM003 £15 MICKY THOMAS LOU MACARI 8X10” MAN UTD 8X10” OR 8X12” FPJ001 JOEY JONES (LIVERPOOL) & JIMMY GREENHOFF (MAN UNITED) 8X12” .....£20 FPM002 GORDON MCQUEEN 10X8” MAN UTD ..£20 FPD009 £25 FPO005 JOHN O’SHEA 8X10” MAGAZINE PAGE ...£5 TOMMY DOCHERTY FPV007A RUUD VAN NISTELROOY 8X12” 8X10” MAN UNITED PSV EINDHOVEN ..............................£25 West Ham FPB038A TREVOR BROOKING 12X8 WEST HAM . £20 FPM042A ALVIN MARTIN 8X10” WEST HAM ...... £10 FPC033 ALAN CURBISHLEY 8X10 WEST HAM ... £10 FPN014A MARK NOBLE 8X12” WEST HAM ......... £15 FPD003 JULIAN DICKS 8X10” WEST HAM ........ £15 FPP006 GEOFF PIKE 8X10” WEST HAM ........... £10 FPD012 GUY DEMEL 8X12” WEST HAM UTD..... £15 FPP009 GEORGE PARRIS 8X10” WEST HAM .. £7.50 FPD015 MOHAMMED DIAME 8X12” WEST HAM £10 FPP012 PHIL PARKES 8X10” WEST HAM ........ -

Digital Television Policies in Greece

D i g i t a l Communication P o l i c i e s | 29 Digital television policies in Greece Stylianos Papathanassopoulos* and Konstantinos Papavasilopoulos** A SHORT VIEW OF THE GREEK TV LANDSCAPE Greece is a small European country, located on the southern region of the Balkan Peninsula, in the south-eastern part of Europe. The total area of the country is 132,000 km2, while its population is of 11.5 million inhabitants. Most of the population, about 4 million, is concentrated in the wider metropolitan area of the capital, Athens. This extreme concentration is one of the side effects of the centralized character of the modern Greek state, alongside the unplanned urbanization caused by the industrialization of the country since the 1960s. Unlike other European countries, almost all Greeks (about 98 per cent of the population) speak the same language, Greek, as mother tongue, and share the same religion, the Greek Orthodox. Greece has joined the EU (then it was called the European Economic Community) in the 1st of January, 1981. It is also a member of the Eurozone since 2001. Until 2007 (when Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU), Greece was the only member-state of the EU in its neighborhood region. Central control and inadequate planning is a “symptom” of the modern Greek state that has seriously “infected” not only urbanization, but other sectors of the Greek economy and industry as well, like for instance, the media. The media sector in Greece is characterized by an excess in supply over demand. In effect, it appears to be a kind of tradition in Greece, since there are more newspapers, more TV channels, more magazines and more radio stations than such a small market can support (Papathanassopoulos 2001). -

Channels List

INFORMATION COVID19 UPDATE NEWS | NETWORKS NBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBS HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS WGN TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNN HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS CTV NEWS HD NEWS | NETWORKS CP 24 NEWS | NETWORKS BNN NEWS | NETWORKS BLOOMBERG HD NEWS | NETWORKS BBC WORLD NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS MSNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS AL JAZEERA ENGLISH NEWS | NETWORKS FOX Pacific NEWS | NETWORKS WSBK NEWS | NETWORKS CTV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CTV BC NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Winnipeg NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Regina NEWS | NETWORKS CTV OTTAWA HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TWO Ottawa NEWS | NETWORKS CTV EDMONTON NEWS | NETWORKS CBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBC TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CBC News Network NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV BC NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV CALGARY NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CITY TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CITY VANCOUVER NEWS | NETWORKS WBTS NEWS | NETWORKS WFXT NEWS | NETWORKS WEATHER CHANNEL USA NEWS | NETWORKS MY 9 HD NEWS | NETWORKS WNET HD NEWS | NETWORKS WLIW HD NEWS | NETWORKS CHCH NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 1 NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 2 NEWS | NETWORKS THE WEATHER NETWORK NEWS | NETWORKS FOX BUSINESS NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 Miami NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 San Diego NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 12 San Antonio NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 13 HOUSTON NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 2 ATLANTA NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 4 SEATTLE NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 5 CLEVELAND NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 9 ORANDO HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 6 INDIANAPOLIS HD NEWS | NETWORKS