Demarcation Between Sacred Space and Profane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Roots Movement: an Awakening! History, Beliefs, Apologetics, Criticisms, Issues Fourth Edition 4.04 6/20/20

Preface 1 Preface The Hebrew Roots Movement: An Awakening! History, Beliefs, Apologetics, Criticisms, Issues Fourth Edition 4.04 6/20/20 by Michael G. Bacon Copyright © 2011-2020 All Rights Reserved Pursuant to 17 U.S. Code § 107, certain uses of copyrighted material "for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright." Under the 'fair use' rule of copyright law, an author may make limited use of another author's work without asking permission. Fair use is based on the belief that the public is entitled to freely use portions of copyrighted materials for purposes of commentary and criticism. The fair use privilege is perhaps the most significant limitation on a copyright owner's exclusive rights. The public domain version of the King James Version, published in 1769 and available for free on the E-Sword® Bible Computer Program, is primarily utilized with some contemporary word updates of my own: e.g. thou=you, saith=say, LORD=YHVH. This is a FREE Book It is NOT to be Sold And as ye go, preach, saying, The kingdom of heaven is at hand. Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out devils: freely ye have received, freely give. —Jesus the Christ / Yeshua haMashiach (Matthew 10:7-8) Important Note: Please refer to http://www.ourfathersfestival.net/hebrew_roots_movement for the latest edition. There are old editions of this book still circulating on the internet. 2 Preface 4.04 June 10, 2020 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: (Added Anglo-Israelism article quote). -

The American University of Rome Religious Studies Program

Disclaimer: This is an indicative syllabus only and may be subject to changes. The final and official syllabus will be distributed by the Instructor during the first day of class. The American University of Rome Religious Studies Program Department or degree program mission statement, student learning objectives, as appropriate Course Title: Sacred Space: Religious Architecture of Rome Course Number: AHRE 106 Credits & hours: 3 credits – 3 hours Pre/Co‐Requisites: None Course description The course explores main ideas behind the sacral space on the example of sacral architecture of Rome, from the ancient times to the postmodern. The course maximizes the opportunity of onsite teaching in Rome; most of the classes are held in the real surrounding, which best illustrates particular topics of the course. Students will have the opportunity to learn about different religious traditions, various religious ideas and practices (including the ancient Roman religion, early Christianity, Roman Catholicism, Orthodoxy and Protestantism, as well as the main elements of religion and sacred spaces of ancient Judaism and Islam). Students will have the opportunity to experience a variety of sacred spaces and learn about the broader cultural and historical context in which they appeared. Short study trips outside of Rome may also take place. Recommended Readings (subject to change) (Only selected chapters must be read, according to weekly schedule) Erzen, Jale Nejdet. "Reading Mosques: MeaningSyllabus and Architecture in Islam," in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Winter, 2011, Vol. 69, 125‐131. Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. Sacred Power, Sacred Space: An Introduction to Christian Architecture and Worship. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. -

Author of the Gospel of John with Jesus' Mother

JOHN MARK, AUTHOR OF THE GOSPEL OF JOHN WITH JESUS’ MOTHER © A.A.M. van der Hoeven, The Netherlands, updated June 6, 2013, www.JesusKing.info 1. Introduction – the beloved disciple and evangelist, a priest called John ............................................................ 4 2. The Cenacle – in house of Mark ánd John ......................................................................................................... 5 3. The rich young ruler and the fleeing young man ............................................................................................... 8 3.1. Ruler (‘archōn’) ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Cenacle in the house of Nicodemus and John Mark .................................................................................... 10 Secret disciples ............................................................................................................................................ 12 3.2. Young man (‘neaniskos’) ......................................................................................................................... 13 Caught in fear .............................................................................................................................................. 17 4. John Mark an attendant (‘hypēretēs’) ............................................................................................................... 18 4.1. Lower officer of the temple prison .......................................................................................................... -

Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple

DOI: 10.4467/25438700ŚM.17.058.7679 MYROSLAV YATSIV* Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple Abstract Main tendencies, appropriateness and features of the embodiment of the architectural and theological essence of the light are defined in architecturally spatial organization of the Orthodox Church; the value of the natural and artificial light is set in forming of symbolic structure of sacral space and architectonics of the church building. Keywords: the Orthodox Church, sacral space, the light, architectonics, functions of the light, a system of illumination, principles of illumination 1. Introduction. The problem raising in such aspect it’s necessary to examine es- As the experience of new-built churches testifies, a process sence and value of the light in space of the of re-conceiving of national traditions and searches of com- Orthodox Church. bination of modern constructions and building technologies In religion and spiritual life of believing peo- last with the traditional architectonic forms of the church bu- ple the light is an important and meaningful ilding in modern church architecture of Ukraine. Some archi- symbol of combination in their imagination tects go by borrowing forms of the Old Russian church archi- of the celestial and earthly worlds. Through tecture, other consider it’s better to inherit the best traditions this it occupies a central place among reli- of wooden and stone churches of the Ukrainian baroque or gious characters which are used in the Saint- realize the ideas of church architecture of the beginning of ed Letter. From the first book of Old Testa- XX. In the east areas the volume-spatial composition of the ment, where the fact of creation of the light Russian “synod-empire” of the church style is renovated as by God is specified: “And God said: “Let it be the “national sign of church architecture” and interpreted as light!”(Genesis 1.3-4), to the last New Testa- the new “Ukrainian Renaissance” [1]. -

Teshuvah: Being Your Best Self!

TESHUVAH: BEING YOUR BEST SELF! During the days leading up to and including Rosh Hashanah, we spend a lot of time in shul asking Hashem for forgiveness for things we may have done wrong over the course of the year, and we ask for a successful year, a healthy year, and a peaceful year. Also, we are encouraged to reach out to people who maybe we have not spoken to in a while or people we may have had disagreements with and make amends. We can all think to ourselves and make a list of people who might appreciate a phone call, or might be excited to get a text, or wants to become friends again. The months of Elul and Tishrei which contain Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, focus specifically on the middot and character traits of repentance, charity, and prayer. So let’s explore how we can include this attribute of Teshuvah (Repentance) this Rosh Hashanah season, and why it is so important! Teshuvah) which is translated as Repentance) -תְּׁשּובָה This is the act of us righting a wrong, big or small, and it can take place whether it’s between you and a friend, or you and Hashem! During the days leading up to Rosh Hashanah, it is a special time for us to ask for forgiveness and work on ourselves. WHAT ARE 3 THINGS I CAN WORK ON? (It can be something as small as trying to say good things about other people or letting your younger sibling pick what TV show to watch). Fill in below: ____________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Sacred Architecture in the Area of Historical Volhynia

E3S Web of Conferences 217, 01007 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021701007 ERSME-2020 Sacred architecture in the area of historical Volhynia Liliia Gnatiuk1,* 1National Aviation University, Interior Design Department, Faculty of architecture, construction and design, Kyiv, Ukraine Abstract. This article discusses the genesis and historical development of the sacred complexes of historic Volhyn. Based on historical and architectural analysis, it is presented that sacred complexes of historic Volhynia were built according to the canons of temple architecture, and at the same time they have their own characteristics, related to national traditions and regional features which appeared as a result of the process of forming Christianity as a religion associated with national development in the specific study territory. The results of a comprehensive analysis of historical and archival documents found in the archives of Ukraine, Poland and Russia, as well as field research are presented. Results of system and theoretical research of significant retrospective analysis of canonical, historical and political prerequisites of sacral complexes were generalized. The concept of sacred complex structures throughout ХІ-ХІХ th centuries is suggested in correlation with the change of religious identity formation and differentiation according to religious requirements. Existence of autochthonous traditions and genuine vector of the Volhynia’s sacred complex development, considering the specific geopolitical location between East and West in the area where two different cultures collide with each other has been proved. The work is shifting statements concerning direct borrowing of architectural and stylistic components of architectural and planning structure and certain decorative elements. 1 Introduction Architecture more than other forms of art reflects the state of society, its political level, the degree of economic development, aesthetic tastes and preferences. -

Exclusion from the Sanctuary and the City of the Sanctuary in the Temple Scroll

EXCLUSION FROM THE SANCTUARY AND THE CITY OF THE SANCTUARY IN THE TEMPLE SCROLL by LA WREN CE H. SCHIFFMAN New York University, New York, N. Y. 10012 Introduction The discovery and publication of the Temple Scroll (Yadin, 1977, 1983; abbreviated below as 11 QT) opened new vistas for the study of the history of Jewish law in the Second Commonwealth period. Immedi ately after the Hebrew edition of the scroll appeared, debate ensued about whether this scroll was to be seen as an integral part of the corpus authored by the Qumran sect, or simply as a part of its library (cf. Schiffman, 1983a, 1985c). This question was, in turn, related to the problem of whether this text reflects generally held beliefs of most Second Temple Jews, or whether its laws and sacrificial procedures represented only the views of its author(s), who were demanding a thor oughgoing revision of the sacrificial worship of the Jerusalem Temple, or, finally, whether it reflected the author's eschatological hopes. This question is crucial in regard to the laws pertaining to various classes of individuals who were to be excluded from the Temple, its city (known in the Temple Scroll as cir hammiqdiis, "the city of the sanc tuary" or "Temple city") and the other cities of Israel because of various forms of ritual impurity or other disqualifications. The editor of the scroll, Yigael Yadin, maintained that it represented a point of view substantially stricter than that of the somewhat later tannaitic sources, and that the scroll extended all prohibitions of such impurity to the entire city of Jerusalem at least. -

Emuna/7/Trustworthiness1

Tikki • Project Currici Draft. February 2014 Emuna/7/TrUStWOrthineSS1 While Emunah is usually translated as faith, in this session we focus on its related meaning - Trustworthiness. Emunah shares a Hebrew root with Oman, an artisan - someone who can be trusted or relied upon to produce a quality product. Emunah is that quality of reliability that we engender in others through our sustained honesty and consideration. A person or institution that acts with Emuno/i/trustworthiness is one in which you can have faith. Emunah as Fundamental to Life -Talmud Bavli Shabbat 31a and Tosafot The prophet lsaiah(33:6) describes some of the positive attributes of the Jewish people as follows: "Faithfulness to Your charge was [her] wealth, wisdom and devotion [her] triumph, reverence for God - that was her treasure." The word used for "Faithfulness" is "Emunah." The rabbis of the Talmud relate each phrase in Isaiah's passage to one of the six sections of the Mishnah, the 3rd century encyclopedia of Jewish law. The word 'faithfulness/EmL/nar?' in the verse refers to the section of Mishnah, "Seeds," that deals with agriculture. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a) The Tosafot, 13th centuryTalmud commentators, explore the relationship between the term "Emunah" and agriculture: The farmer who sows seeds places his faith in the Lifegiver of All the Worlds, for he trusts that God will provide all that is needed for his crops to grow. Ifthe farmer didn't trust at some level that the seeds would grow in the ground s/he would probably not go to the effort to hoe and plow and do all the work needed to produce crops. -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr. -

Relations Between the Traditional Wooden Sacral Architecture of the Podhale Region and Contemporary Architecture of Churches

European Scientific Journal December 2013 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.3 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 RELATIONS BETWEEN THE TRADITIONAL WOODEN SACRAL ARCHITECTURE OF THE PODHALE REGION AND CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE OF CHURCHES Kinga Palus, Dr. Faculty of Architecture, Silesian University of Technology, Gliwice, Poland Abstract The issues of building engineering in mountain regions, especially shaping sacral buildings over the centuries, beginning from traditional architecture of wooden Gothic churches to the churches built nowadays, form an interesting study topic. The Podhale region is both extremely difficult and interesting for modern authors of sacral parchitecture.The tradition of architectural works of wooden churches in Dębno, Obidowa, Grywałd and Harklowa created certain unique models of churches integrated with the conditions of the mountainous climate and landscape aspects. The article aims to answer the author's following question: when designing contemporary sacral buildings in the Podhale region are we to preserve the principles formed over the centuries, following the regional tradition of wooden Gothic churches or ones strictly connected with the style of Witkiewicz architecture, or shall we make attempts at their contemporary interpretation, at the same time preserving universal values so as not to lose the regional identity - continuity of tradition, which currently seems to be a signal of a crisis of our civilization? Keywords: Cultural heritage, tradition, contemporaneity, cultural region, architectural region Introduction: The Podhale region is an interesting study field from a scientific point of view. The author became interested in taking up the topic after multiple trips to the Podhale region during which she had an opportunity to get to know the buildings personally and realize that Podhale, thanks to the specificity of the place, developed as a result of an evolutionary process patterns worth analyzing. -

John's Self-Identification to the Priests and Levites

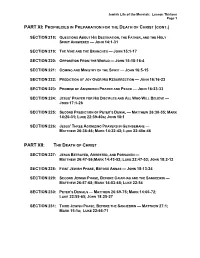

Jewish Life of the Messiah: Lesson Thirteen Page 1 PART XI: PROPHECIES IN PREPARATION FOR THE DEATH OF CHRIST (CONT.) SECTION 218: QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DESTINATION, THE FATHER, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT ANSWERED — JOHN 14:1-31 SECTION 219: THE VINE AND THE BRANCHES — JOHN 15:1-17 SECTION 220: OPPOSITION FROM THE WORLD — JOHN 15:18-16:4 SECTION 221: COMING AND MINISTRY OF THE SPIRIT — JOHN 16:5-15 SECTION 222: PREDICTION OF JOY OVER HIS RESURRECTION — JOHN 16:16-22 SECTION 223: PROMISE OF ANSWERED PRAYER AND PEACE — JOHN 16:23-33 SECTION 224: JESUS’ PRAYER FOR HIS DISCIPLES AND ALL WHO WILL BELIEVE — JOHN 17:1-26 SECTION 225: SECOND PREDICTION OF PETER’S DENIAL — MATTHEW 26:30-35; MARK 14:26-31; LUKE 22:39-40A; JOHN 18:1 SECTION 226: JESUS’ THREE AGONIZING PRAYERS IN GETHSEMANE — MATTHEW 26:36-46; MARK 14:32-42; LUKE 22:40B-46 PART XII: THE DEATH OF CHRIST SECTION 227: JESUS BETRAYED, ARRESTED, AND FORSAKEN — MATTHEW 26:47-56;MARK 14:43-52; LUKE 22:47-53; JOHN 18:2-12 SECTION 228: FIRST JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE ANNAS — JOHN 18:13-24 SECTION 229: SECOND JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE CAIAPHAS AND THE SANHEDRIN — MATTHEW 26:57-68; MARK 14:53-65; LUKE 22:54 SECTION 230: PETER’S DENIALS — MATTHEW 26:69-75; MARK 14:66-72; LUKE 22:55-65; JOHN 18:25-27 SECTION 231: THIRD JEWISH PHASE, BEFORE THE SANHEDRIN — MATTHEW 27:1; MARK 15:1A; LUKE 22:66-71 Jewish Life of the Messiah: Lesson Thirteen Page 2 SECTION 218: QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DESTINATION, THE FATHER, AND THE HOLY SPIRIT ANSWERED—JOHN 14:1-31 PROMISES AND ADMONITIONS BY THE KING Better known as ―The Upper Room Discourse‖ Chapters 14-17 record His table talk during the Passover Seder John, being more interested in what Jesus said rather than what He did, is the only one who records all that was said here. -

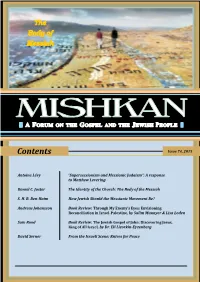

Contents Issue 74, 2015

The Body of Messiah Contents Issue 74, 2015 Antoine Lévy “Supersessionism and Messianic Judaism”: A response to Matthew Levering Daniel C. Juster The Identity of the Church: The Body of the Messiah S. H. R. Ben-Haim How Jewish Should the Messianic Movement Be? Andreas Johansson Book Review: Through My Enemy’s Eyes: Envisioning Reconciliation in Israel-Palestine, by Salim Munayer & Lisa Loden Sam Rood Book Review: The Jewish Gospel of John: Discovering Jesus, King of All Israel, by Dr. Eli Lizorkin-Eyzenberg David Serner From the Israeli Scene: Knives for Peace Mishkan Published by Caspari Center for Biblical and Jewish Studies © 2015 by Caspari Center, Jerusalem Editorial Board Rich Robinson, PhD Richard Harvey, PhD Judith Mendelsohn Rood, PhD Raymond Lillevik, PhD Elliot Klayman, JD Elisabeth E. Levy David Serner Sanna Erelä Linguistic editor and layout: C. Osborne Cover design: Heidi Tohmola ISSN 0792-0474 Subscriptions: $10/year (2 issues) Subscriptions, back issues, and other inquiries: [email protected] www.caspari.com Mishkan A FORUM ON THE GOSPEL AND THE JEWISH PEOPLE ISSUE 74 / 2015 www.caspari.com Introduction Dear readers, We are happy to present this year’s second online issue of Mishkan. In this issue you can read about supersessionism and Messianic Judaism, the identity of the church and the body of Messiah. We also ask, “How Jewish should the Messianic movement be?” And as always, you will find book reviews and reflections on life in Israel. We at the Caspari Center wish you a Happy Hanukkah, Merry Christmas, and Happy New Year 2016, each according to his or her choice and tradition.