Teachers' Unions in Hard Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning from the Leaders Welfare Reform in the Midwestern States

Chapter 1 LEARNING FROM MIDWESTERN LEADERS Carol S. Weissert Few, if any, intergovernmental programs in recent memory have received the academic, political, and public attention of the 1996 federal Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconcilia- tion Act (PRWORA), which abolished Aid to Families with Depend- ent Children (AFDC) and replaced it with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). The 1996 legislation, which converted wel- fare from an entitlement program administered by the states to block grants that states can use as they see fit, has led to intense me- dia attention and legislative debate, as well as numerous studies and information sources.1 State welfare reform efforts that both preceded and emanated from the 1996 federal law are difficult to encapsulate in any one re- port or study. The difficulty lies partly in the fact that welfare re- form encompasses economic and administrative dilemmas at the national, state, and local levels, and also affects recipients in myriad ways. Many state welfare programs incorporate both conservative and liberal ideas and centralize some functions while dispersing others to local control. In so doing, they reflect the federal legislation that helped shape — if not spawn — much of the state action. One way to capture the nuances of some of this complexity — and thus to better understand the nature and potential outcomes of the experiment on which the nation has embarked—is to focus on a few key states. That is what this book does. The authors take a close 1 Learning from the Leaders: Welfare Reform and Policy in Five Midwestern States look at the political forces propelling welfare reform in Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. -

Look to the Governors— Federalism Still Lives by Karlyn H

Chapter 4 Table 1: House Vote, By Income Group 1994 1996 1998 D R D R D R Less than $15,000 60% 37% 61% 36% 57% 39% $15,000-$30,000 50 48 54 43 53 44 $30,000-$50,000 44 54 49 49 48 49 $50,000-$75,000 45 54 47 52 44 54 $75,000+ 38 61 39 59 45 52 Source: Surveys by Voter News Service. tion, health care, Social Security. The effect was predictable: or more is growing rapidly and can’t be taken for granted a significant shift in support from Republican candidates to anymore. The GOP must decide what issues will allow it to Democratic ones. That result creates a dilemma for the GOP hold onto the gains made among non-affluent voters while not as it looks ahead to the next House elections. On the one hand, losing any more ground with the affluent. whatever the causes for the GOP’s loss of support among the affluent, those same causes apparently helped Republicans The extent to which the Republicans are successful, and gain enough ground with non-affluent voters to hold onto a the extent to which the Democrats can thwart their strategy, House majority. But the voter bloc of those making $75,000 could determine who controls the House in 2000. Look to the Governors— Federalism Still Lives By Karlyn H. Bowman In his 1988 book, Laboratories of Democracy, political Eight of the country’s ten most populous states have Republi- writer David Osborne urged readers to look beyond Washing- can governors. -

House Resolution No

The Speaker, on behalf of the entire membership of the House of Representatives, offered the following resolution: House Resolution No. 363. A resolution for the Honorable Alma G. Stallworth. Whereas, It is truly an honor and a privilege to salute Alma G. Stallworth as she brings to a close a long and distinguished career of service within the Michigan House of Representatives. Indeed in the era of term limits, Alma Stallworth's tenure in the House of Representatives is unique in that it has included terms over the course of three decades. She served under the leadership of four governors: William Milliken, James Blanchard, John Engler, and Jennifer Granholm; and five Speakers of the House of Representatives: William Ryan, Gary Owen, Lou Dodak, Curtis Hertel, and Paul Hillegonds; and Whereas, Alma Stallworth was the first female appointed chair of the House Public Utilities Committee, serving twelve years and forging major changes in state energy and communications policies. This record is more than a reflection of her spirit of public service and dedication, it is a sterling tribute to the respect in which she is held by the people of her district. There could be no finer testimony of her valuable accomplishments; and Whereas, Alma Stallworth received her master's degree in Education and Health Promotion from Chelsea University in London, England. She is better prepared to serve others, particularly the youth and families within her community. Youth services to neighborhood and civic organizations have derived great benefit from her service. This commitment has been evident in all of her varied roles in the House of Representatives. -

He Road to Charlottesville T the 1989 Education Summit

covers.qx4 12/2/1999 10:11 AM Page 3 he Road to Charlottesville T The 1989 Education Summit A Publication of the National Education Goals Panel covers.qx4 12/2/1999 10:11 AM Page 4 Current Members National Education Goals Panel Governors Paul E. Patton, Kentucky (D), Chairman 1999 John Engler, Michigan (R) Jim Geringer, Wyoming (R) James B. Hunt, Jr., North Carolina (D) Frank Keating, Oklahoma (R) Frank O’Bannon, Indiana (D) Tommy Thompson, Wisconsin (R) Cecil H. Underwood, West Virginia (R) Members of the Administration Michael Cohen, Special Assistant to the U.S. Secretary of Education (D) Richard W. Riley, U.S. Secretary of Education (D) Members of Congress U.S. Senator Jeff Bingaman, New Mexico (D) U.S. Senator Jim Jeffords, Vermont (R) U.S. Representative William F. Gooding, Pennsylvania (R) U.S. Representative Matthew G. Martinez, California (D) State Legislators Representative G. Spencer Coggs, Wisconsin (D) Representative Mary Lou Cowlishaw, Illinois (R) Representative Douglas R. Jones, Idaho (R) Senator Stephen Stoll, Missouri (D) Executive Director Ken Nelson negp30a.qx4 12/2/1999 10:18 AM Page iii he Road to Charlottesville T The 1989 Education Summit Maris A. Vinovskis Department of History, Institute for Social Research, and School of Public Policy University of Michigan September 1999 A Publication of the National Education Goals Panel negp30a.qx4 12/2/1999 10:18 AM Page iv Paper prepared for the National Education Goals Panel (NEGP). I am grateful to a number of individuals who have provided assistance. I want to thank Emily Wurtz of NEGP and EEI Communications in Alexandria, Virginia, for their editorial assis- tance. -

BEFORE the FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION in the Matter of MUR

BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION In the Matter of 1 ) MUR 4885 1 RESPONSE OF THE REPUBLICAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE TO THE SUBPOENA TO PRODUCE DOCUMENTS AND ORDER TO SUBMIT WRITTEN ANSWERS The FLepublican National Committee ("RNC") hereby responds to the Subpoena to Produce Documents and Order to Subinit Written Answers issued by the Federal Election Conimission ("Commission") in the above-referenced matter. I'ursuant to the Commission's Instructions and Document Requests and Interrogatories. thc discovery request is limited to documents and information from February I, 1995 to present, relating to the April 3, 1995 combined $1 5,000 contribution inadc to the RNC by Mr. Gary G. Jacobs and his wife. It should also be noted that the RNC has redacted certain non-responsive portions of document,s that i: is submitting to the Commission. The RNC nssures the Commission that these redacted areas do not include information requested by the Commission in the above-referenced matter. Furthermore, although the Commission's Subpoena and Order refercncc an attachment of "March 27, I998 Correspondence from I Ialcy R. Barbour (1 pagc)," the RNC did not receive the referenced attachinent. Since the RNC could not take into account said attachment when foriiiulating its response, the RNC hereby rcservcs the right to supplement its response after receiving the attachment in question from the Commission. WRITTEN ANSWERS A. C'onc.e,ning the solicircrriot?qf'the conrr.ihirtion: 1. The solicitation was made by Mr. Wayne Bemian, a member of tlilc 1995 RNC Gala Committee. during a .Innirary, 199s "plionc day" pledgc drivc at tlie Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. -

The Origination of Michigan's

THE ORIGINATION OF MICHIGAN’S CHARTER SCHOOL POLICY: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS By James N. Goenner A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Educational Administration 2011 ABSTRACT THE ORIGINATION OF MICHIGAN’S CHARTER SCHOOL POLICY: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS By James N. Goenner In 1993, Michigan Governor John Engler called the bluff of a political rival, which resulted in the nearly overnight elimination of Michigan’s school funding system and created an opportunity for him to advance his vision for broader educational reform. This study illustrates how Engler functioned as a public policy entrepreneur to take advantage of this window of opportunity in order to advance his vision for a competitive educational marketplace. The idea of using choice and competition to create an educational marketplace had been commonly associated with attempts to privatize public education through vouchers. This posed a seemingly impossible hurdle for Engler, as Michigan’s Constitution has a strict prohibition preventing public funds from being used by non-public schools. Engler was an avid reader and was always searching for new ideas. So when charter schools began to emerge on the educational landscape as a way to withdraw the exclusive control schools districts held over the provision of public education and establish new public schools that could provide choice and competition to the extant system, Engler was intrigued. Applying Schneider, Teske & Mintrom’s (1995) theory of public policy entrepreneurs, the study shows how Engler performed the three essential functions that all entrepreneurs undertake to accomplish their goals in order to originate Michigan’s charter school policy. -

Selection Jury

The Broad Prize 2002 Selection Jury Lamar Alexander, Former US Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander is currently the Goodman visiting professor of the practice of public service at Harvard University. He is a former United States Secretary of Education, Governor of Tennessee and President of the University of Tennessee. As the Secretary of Education, he helped former President Bush push for higher academic standards, "break the mold schools" and a GI Bill for Kids to give poor families more choices of good schools. As Governor, Alexander helped Tennessee become the first state to pay teachers more for teaching well. As Chairman of the National Governors Association, he began "Time for Results", the governors' five-year initiative to create better schools. The Education Commission of the States and the National Collegiate Athletic Association have given him their highest honors, the James B. Conant and Teddy Roosevelt awards. Henry Cisneros, Chairman and CEO, American CityVista Henry Cisneros is Founder and Chairman of American CityVista, a joint homebuilding venture he formed with Kaufman and Broad (now KB Home) in August of 2000. Previously, he was President and Chief Operating Officer of Univision Communications in Los Angeles, the Spanish-language broadcaster that has become the fifth most-watched television network in the nation. In 1993, he became President Clinton’s first Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Cisneros was the first Hispanic American mayor of a major U.S. city when he was elected Mayor of San Antonio in 1981. During his four terms as Mayor of San Antonio, Cisneros helped rebuild the city’s economic base and created jobs through massive infrastructure and downtown improvements, making San Antonio one of the most progressive cities in the nation. -

Download Our Apps Today (Or Simply Surf to Mackinac.Org on Your Mobile Phone)

The Newsletter of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy www.mackinac.org FALL 2012 Check the MIballot2012.org flap! MIballot2012.org MIballot2012.org A QUICK Michigan voters will face a multitude of ballot REFERENCE GUIDE TO proposals when they go to Michigan’S the polls this November. BALLOT Several proposals involve PROPOSALS special constituencies, Senior Investigative Reporter Anne Schieber: particularly public-sector Proposal 1: unions. Referendum on the The “collective bargaining” Emergency Manager Law Tales From a Hot Dog Cart amendment, for example, Referendum on a 2011 state would allow unions t’s unpredictable what sets off a sixth or seventh to call. I was the first. law that expanded the authority firestorm. I am referring, of course, The media was missing this or simply of state-appointed emergency unprecedented power toI the case of 13-year-old Nathan not recognizing how outrageous it truly managers in fiscally failing school over legislators. Another districts and local governments. Duszynski, who wanted to help his was. Nathan’s mother, Lynette Johnson, The expanded powers include measure would provide struggling family by running a hot dog answered the phone and began invalidating government union constitutional protection labor agreement provisions. cart in downtown Holland. Nathan’s reiterating his story, with for the unionization of fledgling business was shut down within an additional bombshell. Proposal 2: home-based caregivers who minutes of opening by a city zoning She and Nathan’s stepfather The ‘Collective Bargaining’ receive Medicaid payments. Amendment officer. Patrick Wright, director of the were hoping Nathan’s business Join the conversation on This proposal would enshrine Mackinac Center Legal Foundation, could turn into a family operation so union collective bargaining power Facebook and Twitter! spotted the story online from the that they could get off government in the Michigan Constitution. -

How Fiscally Conservative? Gary Johnson's Spending Record Vs

Rio Grande Foundation Liberty, Opportunity, Prosperity New Mexico How Fiscally Conservative? Gary Johnson's Spending Record vs. his Republican Contemporaries By Tristan Goodwin with Paul Gessing July 19, 2016 The 2016 presidential election has been like few others. For a number of reasons, the Libertarian Party candidate, former New Mexico Gary Johnson, has gained unprecedented levels of interest as he fights for inclusion in the presidential debates to be held later this year. Fiscally- conservative Republicans, many of whom may be concerned about the rhetoric of their party's standard-bearer Donald Trump, may be looking for alternatives. Former New Mexico governor and current Libertarian Party presidential candidate Gary Johnson is a likely alternative for these disenchanted voters, but his spending record has come under attack from some corners. In a National Review column, writer James Spiller argued that the record of former New Mexico governor and current Libertarian candidate for president Gary Johnson is “not conservative and not even all that libertarian” based largely on Johnson's fiscal record which he further labels “big-government.” Is this true? Is Gary Johnson really just another big-government politician? Before answering that question, it is worth noting that a governor’s role in the budgetary process is necessarily cooperative. Proposing and vetoing the budget cannot accomplish a policy agenda, and when the legislature is held by a different party, it is even harder to hold a governor accountable for every bit of spending which crosses their desk. Deciding how fiscally conservative or liberal a governor is necessitates examining the legislative climate under which they operated. -

Gerald R. Ford Oral History Project John Engler Interviewed by Richard Norton Smith January 27, 2010

Gerald R. Ford Oral History Project John Engler Interviewed by Richard Norton Smith January 27, 2010 Smith: First of all, thank you so much for doing this. Engler: Well, thank you, I’m happy to sit down. Smith: I want to talk a little about you and your entry into the big ring, if you will. You were a leading member of this whole generation of Republican governors, conservative Republican governors, who nevertheless were seen as creative in their conservatism, as problem solvers. I don’t know whether pragmatists is a misnomer or a pejorative, but in any event I would have thought that would have been very, very much Gerald Ford’s style; very reflective of his approach as well. Tell us about your life before it crossed paths with President Ford. Engler: My first meeting with Gerald Ford that I can recall, where I actually had a chance to sit and talk with him, was when Elford [Al] Cederberg, one of his colleagues from the Congress, brought him to Mt. Pleasant, Michigan to speak to a little Lincoln Day dinner for Isabella County. It always struck me, the humility of the leader of the Republicans of the United States House of Representatives out on the road. And, of course, it was only later – I was a rookie state representative, it may have been my first or second term, so I’m in my early twenties in office – and I’m meeting this leader of the Republicans, who’s been in Congress a long time. I was born in ’48; so roughly at the time I was born, he goes there. -

CQ's Governor's Race Rankings — Republican Seats

CQ’s Governor’s Race Rankings — Republican Seats The following are Congressional Quarterly’s rankings of this year’s 23 contests for governorships held by Republican incum- bents. “No Clear Favorite” means neither party has a definite lead. “Leans” means that the named party has an edge, but the con- test appears competitive. “Favored” means that the named party has a definite lead, but an upset cannot be completely ruled out. “Safe Republican” means that the party appears certain to win the contest. State Incumbent First Won Last Vote Contenders Democrat Favored RHODE ISLAND Lincoln C. Almond 1994 51-42% D: State Atty. Gen. Sheldon Whitehouse; ex- (term-limited) (1998) state Sen./’94,’98 gov. nominee Myrth York; state Rep. Tony Pires R: Businessmen Jim Bennett, Don Carcieri Leans Democratic ILLINOIS George H. Ryan 1998 51-47% D: Rep. Rod Blagojevich (retiring) (1998) R: State Atty. Gen. Jim Ryan (nominated in March 19 primary) MICHIGAN John Engler 1990 62-38% D: Rep. David E. Bonior; ex-Gov. Jim Blanchard; (Primary Aug. 6) (term-limited) (1998) state Atty. Gen. Jennifer Granholm R: Lt. Gov. Dick Posthumus; state Sen. Joe Schwarz NEW MEXICO Gary E. Johnson 1994 55-45% D: Ex-Energy Secy./ex-Rep. Bill Richardson (term-limited) (1998) R: State Rep. John Sanchez (nominated in June 4 primary) PENNSYLVANIA Mark Schweiker Moved up N/A D: Ex-Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell (retiring) from lt. gov.2 R: State Atty. Gen. Mike Fisher (nominated in May 21 primary) No Clear Favorite ARIZONA Jane Dee Hull 1998 61-36% D: State Atty. -

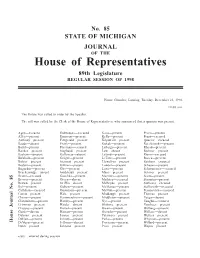

House of Representatives 89Th Legislature REGULAR SESSION of 1998

No. 85 STATE OF MICHIGAN JOURNAL OF THE House of Representatives 89th Legislature REGULAR SESSION OF 1998 House Chamber, Lansing, Tuesday, December 22, 1998. 10:00 a.m. The House was called to order by the Speaker. The roll was called by the Clerk of the House of Representatives, who announced that a quorum was present. Agee—excused Dobronski—excused Kaza—present Profit—present Alley—present Emerson—present Kelly—present Prusi—excused Anthony—present Fitzgerald—present Kilpatrick—present Quarles—excused Baade—absent Frank—present Kukuk—present Raczkowski—present Baird—present Freeman—excused LaForge—present Rhead—present Bankes—present Gagliardi—present Law—absent Richner—present Basham—present Galloway—absent Leland—present Rison—excused Birkholz—present Geiger—present LeTarte—present Rocca—present Bobier—present Gernaat—present Llewellyn—present Sanborn—excused Bodem—present Gilmer—present London—present Schauer—present Bogardus—present Gire—present Lowe—present Schermesser—excused Brackenridge—absent Godchaux—present Mans—present Schroer—present Brater—excused Goschka—present Martinez—present Scott—present Brewer—present Green—absent Mathieu—excused Scranton—present Brown—present Griffin—absent McBryde—present Sikkema—excused Byl—present Gubow—present McManus—present Stallworth—excused Callahan—excused Gustafson—present McNutt—present Tesanovich—excused Cassis—present Hale—present Middaugh—present Thomas—present Cherry—present Hammerstrom—present Middleton—present Varga—absent Ciaramitaro—present Hanley—present Nye—present Vaughn—excused Crissman—present Harder—absent Olshove—present Voorhees—present Cropsey—present Hertel—present Owen—present Walberg—present Curtis—absent Horton—present Oxender—present Wallace—absent Dalman—present Jansen—present Palamara—present Wetters—present DeHart—present Jelinek—present Parks—present Whyman—present House Journal No.DeVuyst—present 85 Jellema—absent Perricone—present Willard—present Dobb—present Johnson—present Price—present Wojno—present e/d/s = entered during session 2734 JOURNAL OF THE HOUSE [December 22, 1998] [No.