Cross-Country Study Economic Policy Challenges in the Baltics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AB BANK SNORAS A.Vivulskio Str

AB BANK SNORAS A.Vivulskio str. 7, LT-03221 Vilnius Interim Condensed Financial Information (not audited) III quarter 2009 AB Bank SNORAS Interim condensed consolidated financial statements for the 9-month period ended 30 September 2009 (LTL thousand) STATEMENTS OF INCOME Financial Group Bank 30 30 30 30 September September September September 2009 2008 2009 2008 Interest income On loans to customers 334.999 311.370 211.113 191.954 On debt securities acquired 23.712 29.328 10.335 22.620 On loans and placements with credit institutions 18.870 55.567 15.952 32.683 377.581 396.265 237.400 247.257 Interest expense On deposits (288.242) (202.242) (207.615) (130.706) On placements from credit institutions (10.513) (6.497) (4.610) (3.862) On debt securities issued (27.815) (33.905) (27.386) (33.279) On subordinated loans (6.720) (5.966) (3.443) (3.433) (333.290) (248.610) (243.054) (171.280) Net interest income 44.291 147.655 (5.654) 75.977 (Impairment) of interest earning assets (73.055) (16.883) (31.297) (6.492) Net interest income after impairment of interest earning assets (28.764) 130.772 (36.951) 69.485 Fee and commission income 85.852 100.995 53.244 59.212 Fee and commission expenses (19.563) (22.046) (9.435) (7.314) Net fee and commission income 66.289 78.949 43.809 51.898 Gains less losses from transactions with financial assets designated at fair value through profit or loss 85.457 (2.073) 81.328 (11.066) Gains less losses from transactions with financial instruments classified as held for trading 30.081 (12.076) 30.081 (19.576) Gains -

Market Practice Guide for Securities Settlement

MARKET PRACTICE GUIDE FOR SECURITIES SETTLEMENT 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1. The purpose of the market practice guide ........................................................................... 4 2. Market practice for securities settlement in Estonia ............................................................ 5 2.1. Clearing and settlement organization ................................................................................ 5 2.2. Applicable laws, rules and regulations ............................................................................... 5 2.3. Operating hours and public holidays ................................................................................. 5 2.4. Clearing agents .......................................................................................................... 6 2.5. Clearing and settlement of NASDAQ OMX Tallinn trades ........................................................ 6 2.5.1 Settlement cycle .................................................................................................................... 6 2.5.2. Trading and settlement currency ................................................................................................ 6 2.5.3. Generation of TSE trade information for settlement .......................................................................... 6 2.5.4. Trade enrichments ................................................................................................................ -

Notice of Arbitration ______

Case 1:19-mc-00401-AT Document 3-1 Filed 08/29/19 Page 1 of 20 IN THE ARBITRATION UNDER THE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA ON THE PROMOTION AND RECIPROCAL PROTECTION OF THE INVESTMENTS BETWEEN FUND FOR PROTECTION OF INVESTORS’ RIGHTS IN FOREIGN STATES, Claimant –and– THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA, Respondent NOTICE OF ARBITRATION ______________________________________________________________________________ ALSTON & BIRD LLP 90 Park Avenue New York, NY 10016 Tel: 212-210-9400 Fax: 212-210-9444 –and– Egorov Puginsky Afanasiev & Partners 21, 1st Tverskaya-Yamskaya Str. 125047, Moscow, Russia Tel: +7(495) 935 80 10 Fax: +7 (495) 935 80 11 Counsel for Claimant Case 1:19-mc-00401-AT Document 3-1 Filed 08/29/19 Page 2 of 20 I. INTRODUCTION 1. Fund for Protection of Investors’ Rights in Foreign States (the Fund), a Russian investment fund, hereby requests the institution of arbitration proceedings against the Republic of Lithuania (Lithuania or the State) in accordance with Article 3 of the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules 1976 (UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules). 2. The Fund submits this Notice of Arbitration (the Notice) pursuant to Article 10(2)(d) of the Agreement Between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania on the Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of the Investments signed on 29 June 1999 and entered into force on 24 May 2004 (the Treaty).1 3. The Fund acquired this claim against Lithuania from Vladimir Antonov (Mr. Antonov),2 a Russian national, after Mr. Antonov notified Lithuania of his intent to submit the present claims to arbitration on 4 May 2012 (the Notice of Dispute).3 4. -

AB Bank SNORAS Unaudited Interim Condensed Separate and Consolidated Financial Statements 31 March 2011

AB bank SNORAS Unaudited interim condensed separate and consolidated financial statements 31 March 2011 AB bankas SNORAS Interim financial statements for the 3-month period ended 31 March 2011 (LTL thousand) CONSOLIDATED AND SEPARATE INCOME STATEMENTS For the three months ended 31 March Financial Group Bank 2011 2010 2011 2010 Interest revenue 127,381 126,511 87,879 85,520 Interest expense (73,362) (109,099) (53,253) (74,096) Net interest income 54,019 17,412 34,626 11,424 Fee and commission revenue 31,674 55,902 20,920 40,110 Fee and commission expenses (7,239) (7,461) (3,604) (1,872) Net fee and commission income 24,435 48,441 17,316 38,238 Net trading income (expenses) 6,800 14,644 5,649 9,677 Net gain on financial assets and liabilities designated at fair value through profit or loss (835) 6,093 (1,151) 2,064 Net gain on financial assets and liabilities not measured at fair value through profit or loss 11 (85) - (71) Other operating income 11,739 992 642 9 Total operating income 96,169 87,497 57,082 61,341 Credit loss expense and impairment losses (22,879) (28,409) (23,566) (26,513) Net operating income 73,290 59,088 33,516 34,828 Salaries and benefits (33,377) (31,081) (14,499) (14,391) Depreciation and amortisation (7,442) (7,412) (4,568) (3,946) Other operating expenses (30,854) (27,658) (13,952) (12,367) Total operating expenses (71,673) (66,151) (33,019) (30,704) Profit before income tax 1,617 (7,063) 497 4,124 Income tax expense (121) (465) - - Profit for the year 1,496 (7,528) 497 4,124 Attributable to: Equity holders of the parent 1,470 (5,422) - - Non-controlling interest 26 (2,106) - - 1,496 (7,528) 497 4,124 The accompanying notes are an integral part of these interim condensed consolidated financial statements. -

State-Owned Enterprises in Lithuania Annual Report 2012 SOE Portfolio: Brief Overview

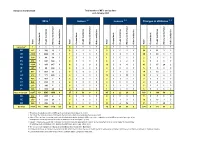

State-Owned Enterprises in Lithuania Annual Report 2012 SOE portfolio: Brief Overview SOE portfolio value SOE portfolio book value of assets SOE portfolio equity value 31 December 2012 13.8 +2.2% 31 December 2012 29.3 -2.2%-31 December 2012 18.3 2.7% 31 December 2011 13.5 31 December 201130.031 December 2011 18.8 LTL billion LTL billion LTL billion 1.0 2.3 1.0 3.5 4.1 3.5 3.5 14.6 8.5 8.9 5.3 5.2 Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises SOE portfolio sales revenue SOE portfolio operating profit SOE portfolio net profit 2012 6,827 +4.3% 2012 4192+155.8% 012 437 +96.6 % 2011 6,544 2011 1642011 222 m LTLm LTL m LTL, normalised profit is provided 40 30 648 644 38 502 67 552 89 249 127 2,455 2,618 210 269 219 100 100 2,892 3,058 -102 -143 -23 -29 2011 2012 2011 2012 2011 2012 Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises SOE portfolio ROE SOE portfolio financial leverage SOE employees 31 December 2012 2.4% 31 December 2012 13.3% 31 December 2012 41,059 -0.7% 31 December 2011 1.2% 31 December 2011 11.1% 31 December 2011 41,33 4 Excluding the interest-free loan to Deposit and Investment Insurance 4.2% 3.5% 6 3.9% , , 27.0% 23 29 23 175 2.5% 3.7% % % 22.5 1.2% 17.2 % % % % % .2 13.2 5 7 14.0 12.7 -1 4 -2.2 1 , , 3 2 8 04 8 00 , , 6 01 6 14 , , 3 86 3 85 0.0% 0.1% Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises Energy Transport Forestry Other enterprises Energy Transport Forestry -

CONSOLIDATED 6 MONTH INTERMEDIARY REPORT of BANKAS SNORAS � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � Vilnius� 2007 � � � 1

CONSOLIDATED 6 MONTH INTERMEDIARY REPORT OF BANKAS SNORAS Vilnius 2007 1. THE PERIOD REVIEWED IN THE ANNUAL REPORT The report covers the first half-year of 2007, all the figures are provided as of June 30, 2007 unless otherwise is stated. Only the main information which changed during the first half-year of 2007 is provided in this intermediary report. 2. MAIN DATA ON THE ISSUER Commercial name of the Issuer: AB bankas „Snoras“ Legal name of the Issuer: AB bankas „Snoras“ Authorised capital: LTL 157 267 200 Registration date and place: March 17, 1992, the Bank of Lithuania Company (register) code: 112025973 Registration No.: AB 92-20 Establishment date: March 17, 1992 Operation period: Unlimited Legal address: A.Vivulskio str. 7, LT-03221 Vilnius Legal – organizational form: Public limited liability company Legislation governing the Issuer’s operations: Law of the Republic of Lithuania Register of the Issuers: State enterprise Centre of Registers Phone numbers: (8~5) 216 27 95, (8~5) 231 01 44 Fax numbers: (8~5) 231 01 55, (8~5) 265 27 00 e-mails: [email protected] Internet site: www.snoras.com 3. NATURE OF THE MAIN TYPE OF ACTIVITY OF THE ISSUER Bank and its subsidiaries offer customers (both legal and natural persons) licensed and unlicensed financial services: accept deposits and other returnable funds from nonprofessional market participants (accumulative deposits in litas and foreign currencies, time deposits or deposits with blank date in litas and foreign currencies), perform wire-transfers (open customers bank accounts in litas -

2003-05-29 Snoras X.4 For.INTERNET.Indd

TURINYS / CONTENTS / СОДЕРЖАНИЕ KREDITO ĮSTAIGŲ VEIKLA 2002 METAIS / 4 OPERATIONS OF CREDIT INSTITUTIONS IN 2002 8 ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТЬ КРЕДИТНЫХ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЙ ЛИТВЫ В 2002 ГОДУ 11 AB BANKO „SNORAS” ISTORIJA / 16 MILESTONES 18 ИСТОРИЯ 19 VALDYBOS PIRMININKO ATASKAITA / 21 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 27 ОТЧЕТ ПРЕДСЕДАТЕЛЯ ПРАВЛЕНИЯ 31 VALDYBA / 36 MANAGEMENT BOARD 37 ПРАВЛЕНИЕ 37 AB BANKO „SNORAS” STRUKTŪRA / 38 ORGANISATIONAL CHART 38 ОРГАНИЗАЦИОННАЯ СТРУКТУРА 38 PERSONALO POLITIKA / 42 PERSONNEL POLICY 43 ПОЛИТИКА В СФЕРЕ ПЕРСОНАЛА 43 BANKO VEIKLOS KRYPTYS / 44 STRATEGY GUIDELINES 45 НАПРАВЛЕНИЯ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ 45 MAŽMENINĖ BANKININKYSTĖ, BANKO TINKLAS / 46 RETAIL BANKING AND SERVICE NETWORK 48 ПРЕДОСТАВЛЕНИЕ РОЗНИЧНЫХ БАНКОВСКИХ УСЛУГ. СЕТЬ ОБСЛУЖИВАНИЯ 48 BANKO TINKLAS / 50 SERVICE NETWORK 50 СЕТЬ ОБСЛУЖИВАНИЯ 50 MOKĖJIMO KORTELĖS / 54 PAYMENT CARDS 58 ПЛАТЕЖНЫЕ КАРТЫ 61 IŽDAS IR INVESTICIJŲ VALDYMAS / 68 TREASURY AND INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT 70 КАЗНАЧЕЙСТВО И УПРАВЛЕНИЕ ИНВЕСТИЦИЯМИ 72 PAGRINDINIAI BANKAI KORESPONDENTAI / 74 BASIC CORRESPONDENT BANKS 74 ОСНОВНЫЕ БАНКИ-КОРРЕСПОНДЕНТЫ 74 KREDITAVIMO POLITIKA / 76 LENDING POLICY 78 КРЕДИТНАЯ ПОЛИТИКА 79 VIDAUS AUDITO TARNYBA / 80 INTERNAL AUDIT 82 СЛУЖБА ВНУТРЕННЕГО АУДИТА 83 RĖMIMAS / 86 SPONSORSHIP 87 БЛАГОТВОРИТЕЛЬНОСТЬ 87 ADRESAI / 88 ADDRESSES 88 АДРЕСА 88 1 KREDITO ĮSTAIGŲ VEIKLA 2002 METAIS 2002 metų pabaigoje Lietuvoje veikė 10 Lietuvos banko licenciją turinčių bankų, 4 užsienio bankų skyriai ir 2 užsienio bankų atstovybės. 2002 metų gegužės mėnesį buvo įsteigtas naujas AB VB būsto kreditų ir obligacijų bankas, kuriam Lietuvos banko valdyba išdavė licenciją su apribojimais. Be to, 2002 metų pra- džioje Lietuvos bankas išdavė licenciją Suomijos Respublikos banko „Nordea Bank Finland Plc” Lietuvos skyriaus veiklai Lietuvos Respublikoje (šis skyrius anks- čiau Lietuvoje veikė „Merita Bank Plc” pavadinimu). 2002 metų kovo mėnesį buvo baigtas AB Lietuvos žemės ūkio banko privatizavimas – Vokietijos Federacinės Respublikos bankas „Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale” iš valstybės įsigijo 76 proc. -

The Consolidated Annual Report of the Public Limited Liability Company Bank SNORAS for 2010

The consolidated annual report of the Public Limited Liability Company Bank SNORAS for 2010 CONTENTS 1. THE PERIOD REVIEWED IN THE ANNUAL REPORT................................................................................... 3 2. THE ISSUER AND ITS CONTACT INFORMATION....................................................................................... 3 3. THE COMPOSITION OF THE GROUP ........................................................................................................ 3 4. THE NATURE OF THE ISSUER’S MAIN ACTIVITY..................................................................................... 10 5. AGREEMENTS WITH INTERMEDIARIES OF PUBLIC TRADING IN SECURITIES ........................................ 10 6. DATA CONCERNING THE TRADING IN ISSUER’S SECURITIES AT THE REGULATED MARKETS ............... 10 7. THE NUMBER AND NOMINAL PRICE OF THE SHARES BELONGING TO THE BANK AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES......................................................................................................................................... 12 8. OBJECTIVE REVIEW OF THE BANK’S STATUS, PERFORMANCE AND DEVELOPMENT, DESCRIPTION OF MAIN RISK TYPES....................................................................................................... 15 9. THE MAIN ASPECTS OF AB BANK SNORAS GROUP INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS RELATED TO FORMATION OF CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL REPORTS .......... 16 10.INFORMATION ABOUT THE INTERNAL CONTROL SYSTEM OF THE BANK............................................. 17 11.ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL -

Baltic Journal of Law & Politics Are Auditors At

BALTIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLITICS A Journal of Vytautas Magnus University VOLUME 9, NUMBER 2 (2016) ISSN 2029-0454 Cit.: Baltic Journal of Law & Politics 9:2 (2016): 171–197 http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/bjlp DOI: 10.1515/bjlp-2016-0017 ARE AUDITORS AT FAULT FOR THE COLLAPSE OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN LITHUANIA? Julija Kiršienė Professor; Dr. Vytautas Magnus University Faculty of Law (Lithuania) Contact information Address: Jonavos str. 66, LT-44191 Kaunas, Lithuania Phone: +370 37 327993 E-mail address: [email protected] Gabrielė Misevičiūtė L.L.M. Vytautas Magnus University Faculty of Law (Lithuania) Contact information Address: Jonavos str. 66, LT-44191 Kaunas, Lithuania Phone: +370 37 751044 E-mail address: [email protected] Received: October 3, 2016; reviews: 2; accepted: December 23, 2016. ABSTRACT The experience of the global financial crisis revealed that while many financial institutions were allowed to take excessive risks, the auditors failed in their duties to reasonably evaluate those risks as well as to inform the investing public about them. The issues of statutory auditors' liability and their public role are particularly relevant in Lithuania, considering the fact that over just the past few years the third and the fourth largest banks in Lithuania turned out to be insolvent. Analysis of legal actions against auditors of these banks highlighted certain shortcomings in the audit market and auditors' BALTIC JOURNAL OF LAW & POLITICS ISSN 2029-0454 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 2 2016 liability regulation, related to the quality and transparency of audit reports, auditors' accountability and independence requirements, and insurance of auditors’ liability. -

Mfis Joiners Leavers Changes in Attributes

European Central Bank Total number of MFIs and updates end-January 2004 MFIs 1 Joiners 2, 3 Leavers 2, 4 Changes in attributes 2, 6 Total Central bank Credit institution Money market fund Other institution Total Central bank Credit institution Money market fund Other institution Total Central bank Credit institution Money market fund Other institution Total Central bank Credit institution Money market fund Other institution Euro area 5 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 BE 127 1 108 18 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 54 0 51 3 0 DE 2278 1 2222 55 0 1 0 1 0 0 4 0 4 0 0 40 0 40 0 0 GR 100 1 60 39 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 0 1 1 0 ES 516 1 347 168 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 1 2 0 3 0 3 0 0 FR 1584 1 933 647 3 8 0 2 6 0 10 0 6 4 0 41 0 15 24 2 IE 285 1 80 204 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 0 5 0 0 IT 857 1 803 53 0 5 0 5 0 0 3 0 3 0 0 14 0 12 2 0 LU 578 1 171 406 0 5 0 2 3 0 19 0 3 16 0 14 0 6 8 0 NL 495 1 483 7 4 5 0 5 0 0 3 0 3 0 0 3 0 3 0 0 AT 828 1 814 11 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 4 0 0 PT 203 1 199 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 5 0 5 0 0 FI 395 1 365 29 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 3 0 3 0 0 Euro area total 7 8247 13 6585 1640 9 25 0 16 9 0 45 0 22 23 0 188 0 148 38 2 DK 206 1 203 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 3 0 0 SE 253 1 222 29 1 3 0 3 0 0 3 0 3 0 0 16 0 13 3 0 GB 460 1 420 39 0 8 0 0 8 0 22 0 6 16 0 27 0 7 20 0 EU total 9166 16 7430 1710 10 36 0 19 17 0 70 0 31 39 0 234 0 171 61 2 1 This shows the absolute number of MFIs at the second last working day of the month. -

Assessment of Competition in the Banking Sector of Lithuania

MOKSLAS – LIETUVOS ATEITIS Verslas XXI amžIuje SCIENCE – FUTURE OF LITHUANIA BUSINESS IN XXI CENTURY ISSN 2029-2341 print / ISSN 2029-2252 online http://www.mla.vgtu.lt 2014 6(1): 56–63 http://dx.doi.org/10.3846/mla.2014.08 ASSESSMENT OF COMPETITION IN THE BANKING SECTOR OF LITHUANIA Sandra Rimavičiūtė1, Mantas Vilys2 Vilnius Gediminas Technical University E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract. Competition in the banking sector is different from the competition in the other sectors. Banks can compete only on the basis of banking products. Also, banks are dependent on each other – actions of every market participant may strongly affect the others. Problems of one bank may encourage distrust of the entire banking system. Analysis of Lithuanian banking sector has showed that country’s banking sector can be divided into three groups – the biggest banks, smaller and medium-sized banks and foreign banks branches. The largest part of banking sector is concentrated in activity of the three banks. All these banks are owned by Scandinavian capital. Lithuanian banking sector is highly concentrated. In 2005–2012 years the average mean of three banks concentration index (CR3) in deposits, assets and loans markets was 68 percent. According to these high values of concentration rates, Lithuanian banking sector can be characterized as oligopoly. Keywords: competition, banking sector, concentration, “k” index, Hirschman (HHI) index. Introduction The banking system in the country’s economy is undenia- Researchers observed different approach both in the ble. None of the modern economy nowadays functions evaluation of competition through theoretical aspect and properly without banks. -

Journal on Baltic Security ______

Journal on Baltic Security _______________________________________________ Volume 2, Issue 2 2016 Journal on Baltic Security Vol 2, Issue 2, 2016 Journal on Baltic Security is the bi-annual publication of the Baltic Defence College © 2016, Baltic Defence College, All rights reserved ISSN 2382-9222 (print) ISSN 2382-9230 (online) Editor-in-chief: Dr. Asta Maskaliūnaitė, Baltic Defence College Assistant editor: Dr Ashley Robert Roden-Bow, Baltic Defence College Editorial Board Dr. Zdzislaw Sliwa, Baltic Defence College, Estonia Dr. Ole Kværnø, Royal Danish Defence College, Denmark Dr. Margarita Šešelgytė, Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University, Lithuania Dr. Žaneta Ozolina, University of Latvia Dr. Andres Kasekamp, Tartu University, Estonia Mr. Marek Menkiszak, Centre for Eastern Studies, Poland Mr. Tomas Jermalavičius, ICDS, Estonia Electronic version of the Journal on Baltic Security can be accessed on the website of the Baltic Defence College at www.baltdefcol.org All articles of the Journal on Baltic Security are also available through EBSCO database, the International Relations and Security Network (ISN) and De Gruyter Open. All inquiries should be made to the Baltic Defence College, Riia 12, 51013 Tartu, Estonia, ph: +372 717 6000, e-mail: [email protected] Disclaimer: The Baltic Defence College publishes the Journal on Baltic Security as a journal of research and commentary on security issues in order to facilitate academic discussion. The views presented in the articles are those only of the authors, and do not represent any official views of the three Baltic States, or their armed forces, or of the Baltic Defence College. Journal on Baltic Security Vol 2, Issue 2, 2016 CONTENTS SPECIAL ISSUE: BALTIC PERCEPTIONS OF SECURITY AFTER UKRAINE Editor´s Note 4 Dovile Jakniunaite.