Musharraf and the Price of Kargil | Prateek Joshi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

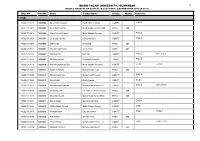

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

Download Article

Pakistan’s ‘Mainstreaming’ Jihadis Vinay Kaura, Aparna Pande The emergence of the religious right-wing as a formidable political force in Pakistan seems to be an outcome of direct and indirect patron- age of the dominant military over the years. Ever since the creation of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1947, the military establishment has formed a quasi alliance with the conservative religious elements who define a strongly Islamic identity for the country. The alliance has provided Islamism with regional perspectives and encouraged it to exploit the concept of jihad. This trend found its most obvious man- ifestation through the Afghan War. Due to the centrality of Islam in Pakistan’s national identity, secular leaders and groups find it extreme- ly difficult to create a national consensus against groups that describe themselves as soldiers of Islam. Using two case studies, the article ar- gues that political survival of both the military and the radical Islamist parties is based on their tacit understanding. It contends that without de-radicalisation of jihadis, the efforts to ‘mainstream’ them through the electoral process have huge implications for Pakistan’s political sys- tem as well as for prospects of regional peace. Keywords: Islamist, Jihadist, Red Mosque, Taliban, blasphemy, ISI, TLP, Musharraf, Afghanistan Introduction In the last two decades, the relationship between the Islamic faith and political power has emerged as an interesting field of political anal- ysis. Particularly after the revival of the Taliban and the rise of ISIS, Author. Article. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 14, no. 4: 51–73. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Khan, Adeeba Aziz (2015) Electoral institutions in Bangladesh : a study of conflicts between the formal and the informal. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/23587 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Electoral Institutions in Bangladesh: A Study of Conflicts Between the Formal and the Informal Adeeba Aziz Khan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Law 2015 Department of Law SOAS, University of London I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

![Air Power and National Security[INITIAL].P65](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1427/air-power-and-national-security-initial-p65-191427.webp)

Air Power and National Security[INITIAL].P65

AIR POWER AND NATIONAL SECURITY Indian Air Force: Evolution, Growth and Future AIR POWER AND NATIONAL SECURITY Indian Air Force: Evolution, Growth and Future Air Commodore Ramesh V. Phadke (Retd.) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES & ANALYSES NEW DELHI PENTAGON PRESS Air Power and National Security: Indian Air Force: Evolution, Growth and Future Air Commodore Ramesh V. Phadke (Retd.) First Published in 2015 Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi ISBN 978-81-8274-840-8 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in Branch Flat No.213, Athena-2, Clover Acropolis, Viman Nagar, Pune-411014 Email: [email protected] In association with Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No. 1, Development Enclave, New Delhi-110010 Phone: +91-11-26717983 Website: www.idsa.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. This book is dedicated to the memory of my parents, Shri V.V. Phadke and Shrimati Vimal Phadke, My in-laws, Brig. G.S. Sidhu, AVSM and Mrs. Pritam Sidhu, Late Flg. Offr. Harita Deol, my niece, who died in an Avro accident on December 24, 1996, Late Flt. -

Kashmir Conflict: a Critical Analysis

Society & Change Vol. VI, No. 3, July-September 2012 ISSN :1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) Kashmir Conflict: A Critical Analysis Saifuddin Ahmed1 Anurug Chakma2 Abstract The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir which is considered as the major obstacle in promoting regional integration as well as in bringing peace in South Asia is one of the most intractable and long-standing conflicts in the world. The conflict originated in 1947 along with the emergence of India and Pakistan as two separate independent states based on the ‘Two-Nations’ theory. Scholarly literature has found out many factors that have contributed to cause and escalate the conflict and also to make protracted in nature. Five armed conflicts have taken place over the Kashmir. The implications of this protracted conflict are very far-reaching. Thousands of peoples have become uprooted; more than 60,000 people have died; thousands of women have lost their beloved husbands; nuclear arms race has geared up; insecurity has increased; in spite of huge destruction and war like situation the possibility of negotiation and compromise is still absence . This paper is an attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of Kashmir conflict as well as its security implications in South Asia. Introduction Jahangir writes: “Kashmir is a garden of eternal spring, a delightful flower-bed and a heart-expanding heritage for dervishes. Its pleasant meads and enchanting cascades are beyond all description. There are running streams and fountains beyond count. Wherever the eye -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 18 RESULT GAZETTE of B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL

18 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021310011 3000002 Syed Afaq Hussain Syed Amin Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310001 3000003 Syed Atif Hussain Syed Sajid Hussain Shah PASS 430 110021310004 3000004 Mahr Ahmad Kamal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310006 3000005 Shahzad Ahmed Ashiq Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310007 3000006 Wali Khan Khowazik PASS 441 110021310013 3000007 Muhammad Ehsan Juma Khan PASS 437 110021310014 3000008 Mujahid Din Roz Din COMPT. ENG:II ENG-LIT:II 110021310015 3000009 Mehtab arshad Arshad Mehmood COMPT. ENG:II 110021310018 3000010 Mahr Muhammad Ijlal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ECO:I ECO:II 110021310021 3000011 Sammar Abbas Muhammad Ismail PASS 436 110021310022 3000012 Muhammad Riaz Muhammad Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310026 3000013 Anas Ayaz Ayaz Ahmad COMPT. ECO:I 110021310027 3000014 Muhammad Shahzad Muhammad khursheed COMPT. ENG:II APP-PSY:II 110021310029 3000015 Shahab U Din Ch Zaheer Ud Din Ahmed PASS 384 110021310031 3000016 Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Sultan Khan PASS 453 110021310033 3000017 Sohail Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal COMPT. ENG:II 110021310034 3000018 Malik Waqar Ahmed Malik Iftikhar Ahmad COMPT. ENG:I 110021310035 3000019 Waqar Haider Ghulam Haider COMPT. ENG:I ENG:II 110021310036 3000020 Arif Zaman Mehran Khan PASS 434 110021310038 3000021 Fahad Raza Muhammad Muslimeen COMPT. ENG:I ENG-LIT:II 110021310039 3000022 Mubasher Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz PASS 423 19 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. -

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

10 Pakistan's Nuclear Program

10 PAKISTAN’S NUCLEAR PROGRAM Laying the groundwork for impunity C. Christine Fair Contemporary analysts of Pakistan’s nuclear program speciously assert that Pakistan began acquiring a nuclear weapons capability after the 1971 war with India in which Pakistan was vivisected. In this conventional account, India’s 1974 nuclear tests gave Pakistan further impetus for its program.1 In fact, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s first popularly elected prime minister, ini- tiated the program in the late 1960s despite considerable opposition from Pakistan’s first military dictator General Ayub Khan (henceforth Ayub). Bhutto presciently began arguing for a nuclear weapons program as early as 1964 when China detonated its nuclear devices at Lop Nor and secured its position as a permanent nuclear weapons state under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Considering China’s test and its defeat of India in the 1962 Sino–Indian war, Bhutto reasoned that India, too, would want to develop a nuclear weapon. He also knew that Pakistan’s civilian nuclear program was far behind India’s, which predated independence in 1947. Notwithstanding these arguments, Ayub opposed acquiring a nuclear weapon both because he believed it would be an expensive misadventure and because he worried that doing so would strain Pakistan’s western alliances, formalized through the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) and the South-East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Ayub also thought Pakistan would be able to buy a nuclear weapon “off the shelf” from one of its allies if India acquired one first.2 With the army opposition obstructing him, Bhutto was unable to make any significant nuclear headway until 1972, when Pakistan’s army lay in disgrace after losing East Pakistan in its 1971 war with India. -

Limited Conflicts Under the Nuclear Umbrella: Indian and Pakistani

Limited Conflicts Under the Nuclear Umbrella R Indian and Pakistani Lessons from the Kargil Crisis Ashley J. Tellis C. Christine Fair Jamison Jo Medby National Security Research Division This research was conducted within the International Security and Defense Policy Center (ISDPC) of RAND’s National Security Research Division (NSRD). NSRD conducts research and analysis for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, the Unified Commands, the defense agencies, the Department of the Navy, the U.S. intelligence community, allied foreign governments, and foundations. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tellis, Ashley J. Limited conflicts under the nuclear umbrella : Indian and Pakistani lessons from the Kargil crisis / Ashley J. Tellis, C. Christine Fair, Jamison Jo Medby. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1450.” ISBN 0-8330-3101-5 1. Kargil (India)—History, Military—20th century. 2. Jammu and Kashmir (India)—Politics and government—20th century. 3. India—Military relations— Pakistan. 4. Pakistan—Military relations—India. I. Fair, C. Christine. II. Medby, Jamison Jo. III. Title. DS486.K3347 T45 2001 327.5491054—dc21 2001048907 RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.